Poverty Mapping in China: Do Environmental Variables Matter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Study on the Effects of Extreme Precipitation for Seven Growth Stages of Winter Wheat in Northern Weihe Loess Plateau, China

Journal of Water Resource and Protection, 2020, 12, 358-380 https://www.scirp.org/journal/jwarp ISSN Online: 1945-3108 ISSN Print: 1945-3094 Study on the Effects of Extreme Precipitation for Seven Growth Stages of Winter Wheat in Northern Weihe Loess Plateau, China Ouk Sereyrorth1,2, Baowen Yan1*, Khem Chunpanha1,2, Porn Lybun1,2, Pich Linvolak1,2 1College of Water Resources and Architectural Engineering, Northwest A&F University, Xianyang, China 2Faculty of Hydrology and Water Resources Engineering, Institute of Technology of Cambodia, Phnompenh, Cambodia How to cite this paper: Sereyrorth, O., Abstract Yan, B.W., Chunpanha, K., Lybun, P. and Linvolak, P. (2020) Study on the Effects of The research on the characteristic frequency of precipitation is a great signi- Extreme Precipitation for Seven Growth ficance for guiding regional agricultural planning, water conservancy project Stages of Winter Wheat in Northern Weihe designs, and drought and flood control. Droughts and floods occurred in Loess Plateau, China. Journal of Water Resource and Protection, 12, 358-380. northern Weihe Loess Plateau, affecting growing and yield of winter wheat in https://doi.org/10.4236/jwarp.2020.124021 the area. Based on the daily precipitation data of 29 meteorological stations from 1981 to 2012, this study is to address the analysis of three different fre- Received: February 29, 2020 quencies of annual precipitation at 5%, 50%, and 95%, and to determine the Accepted: April 18, 2020 Published: April 21, 2020 amount of rainfall excess and water shortage during seven growth stages of winter wheat at 5%, 10%, and 20% frequencies, respectively. Pearson type III Copyright © 2020 by author(s) and curve was selected for this study to analyze the distribution frequency of an- Scientific Research Publishing Inc. -

Chinacoalchem

ChinaCoalChem Monthly Report Issue May. 2019 Copyright 2019 All Rights Reserved. ChinaCoalChem Issue May. 2019 Table of Contents Insight China ................................................................................................................... 4 To analyze the competitive advantages of various material routes for fuel ethanol from six dimensions .............................................................................................................. 4 Could fuel ethanol meet the demand of 10MT in 2020? 6MTA total capacity is closely promoted ....................................................................................................................... 6 Development of China's polybutene industry ............................................................... 7 Policies & Markets ......................................................................................................... 9 Comprehensive Analysis of the Latest Policy Trends in Fuel Ethanol and Ethanol Gasoline ........................................................................................................................ 9 Companies & Projects ................................................................................................... 9 Baofeng Energy Succeeded in SEC A-Stock Listing ................................................... 9 BG Ordos Started Field Construction of 4bnm3/a SNG Project ................................ 10 Datang Duolun Project Created New Monthly Methanol Output Record in Apr ........ 10 Danhua to Acquire & -

ATTACHMENT 1 Barcode:3800584-02 C-570-107 INV - Investigation

ATTACHMENT 1 Barcode:3800584-02 C-570-107 INV - Investigation - Chinese Producers of Wooden Cabinets and Vanities Company Name Company Information Company Name: A Shipping A Shipping Street Address: Room 1102, No. 288 Building No 4., Wuhua Road, Hongkou City: Shanghai Company Name: AA Cabinetry AA Cabinetry Street Address: Fanzhong Road Minzhong Town City: Zhongshan Company Name: Achiever Import and Export Co., Ltd. Street Address: No. 103 Taihe Road Gaoming Achiever Import And Export Co., City: Foshan Ltd. Country: PRC Phone: 0757-88828138 Company Name: Adornus Cabinetry Street Address: No.1 Man Xing Road Adornus Cabinetry City: Manshan Town, Lingang District Country: PRC Company Name: Aershin Cabinet Street Address: No.88 Xingyuan Avenue City: Rugao Aershin Cabinet Province/State: Jiangsu Country: PRC Phone: 13801858741 Website: http://www.aershin.com/i14470-m28456.htmIS Company Name: Air Sea Transport Street Address: 10F No. 71, Sung Chiang Road Air Sea Transport City: Taipei Country: Taiwan Company Name: All Ways Forwarding (PRe) Co., Ltd. Street Address: No. 268 South Zhongshan Rd. All Ways Forwarding (China) Co., City: Huangpu Ltd. Zip Code: 200010 Country: PRC Company Name: All Ways Logistics International (Asia Pacific) LLC. Street Address: Room 1106, No. 969 South, Zhongshan Road All Ways Logisitcs Asia City: Shanghai Country: PRC Company Name: Allan Street Address: No.188, Fengtai Road City: Hefei Allan Province/State: Anhui Zip Code: 23041 Country: PRC Company Name: Alliance Asia Co Lim Street Address: 2176 Rm100710 F Ho King Ctr No 2 6 Fa Yuen Street Alliance Asia Co Li City: Mongkok Country: PRC Company Name: ALMI Shipping and Logistics Street Address: Room 601 No. -

Late Quaternary Activity of the Huashan Piedmont Fault and Associated Hazards in the Southeastern Weihe Graben, Central China

Vol. 91 No. 1 pp.76–92 ACTA GEOLOGICA SINICA (English Edition) Feb. 2017 Late Quaternary Activity of the Huashan Piedmont Fault and Associated Hazards in the Southeastern Weihe Graben, Central China DU Jianjun1, 2, *, LI Dunpeng3, WANG Yufang4 and MA Yinsheng1, 2 1 Institute of Geomechanics, Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences, Beijing 100081, China 2 Key Laboratory of Neotectonic Movement and Geohazard, Ministry of Land and Resources, Beijing 100081, China 3 College of Zijin Mining, Fuzhou University, Fuzhou 350108, China 4 Center of Oil and Gas Resources Survey, China Geological Survey, Beijing 100029, China Abstract: The Weihe Graben is not only an important Cenozoic fault basin in China but also a significant active seismic zone. The Huashan piedmont fault is an important active fault on the southeast side of the Weihe Graben and has been highly active since the Cenozoic. The well–known Great Huaxian County Earthquake of 1556 occurred on the Huashan piedmont fault. This earthquake, which claimed the lives of approximately 830000 people, is one of the few large earthquakes known to have occurred on a high–angle normal fault. The Huashan piedmont fault is a typical active normal fault that can be used to study tectonic activity and the associated hazards. In this study, the types and characteristics of late Quaternary deformation along this fault are discussed from geological investigations, historical research and comprehensive analysis. On the basis of its characteristics and activity, the fault can be divided into three sections, namely eastern, central and western. The eastern and western sections display normal slip. Intense deformation has occurred along the two sections during the Quaternary; however, no deformation has occurred during the Holocene. -

The Spreading of Christianity and the Introduction of Modern Architecture in Shannxi, China (1840-1949)

Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura de Madrid Programa de doctorado en Concervación y Restauración del Patrimonio Architectónico The Spreading of Christianity and the introduction of Modern Architecture in Shannxi, China (1840-1949) Christian churches and traditional Chinese architecture Author: Shan HUANG (Architect) Director: Antonio LOPERA (Doctor, Arquitecto) 2014 Tribunal nombrado por el Magfco. y Excmo. Sr. Rector de la Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, el día de de 20 . Presidente: Vocal: Vocal: Vocal: Secretario: Suplente: Suplente: Realizado el acto de defensa y lectura de la Tesis el día de de 20 en la Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura de Madrid. Calificación:………………………………. El PRESIDENTE LOS VOCALES EL SECRETARIO Index Index Abstract Resumen Introduction General Background........................................................................................... 1 A) Definition of the Concepts ................................................................ 3 B) Research Background........................................................................ 4 C) Significance and Objects of the Study .......................................... 6 D) Research Methodology ...................................................................... 8 CHAPTER 1 Introduction to Chinese traditional architecture 1.1 The concept of traditional Chinese architecture ......................... 13 1.2 Main characteristics of the traditional Chinese architecture .... 14 1.2.1 Wood was used as the main construction materials ........ 14 1.2.2 -

Table of Codes for Each Court of Each Level

Table of Codes for Each Court of Each Level Corresponding Type Chinese Court Region Court Name Administrative Name Code Code Area Supreme People’s Court 最高人民法院 最高法 Higher People's Court of 北京市高级人民 Beijing 京 110000 1 Beijing Municipality 法院 Municipality No. 1 Intermediate People's 北京市第一中级 京 01 2 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Shijingshan Shijingshan District People’s 北京市石景山区 京 0107 110107 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Municipality Haidian District of Haidian District People’s 北京市海淀区人 京 0108 110108 Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Mentougou Mentougou District People’s 北京市门头沟区 京 0109 110109 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Municipality Changping Changping District People’s 北京市昌平区人 京 0114 110114 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Yanqing County People’s 延庆县人民法院 京 0229 110229 Yanqing County 1 Court No. 2 Intermediate People's 北京市第二中级 京 02 2 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Dongcheng Dongcheng District People’s 北京市东城区人 京 0101 110101 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Xicheng District Xicheng District People’s 北京市西城区人 京 0102 110102 of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Fengtai District of Fengtai District People’s 北京市丰台区人 京 0106 110106 Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality 1 Fangshan District Fangshan District People’s 北京市房山区人 京 0111 110111 of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Daxing District of Daxing District People’s 北京市大兴区人 京 0115 -

Preparing the Shaanxi-Qinling Mountains Integrated Ecosystem Management Project (Cofinanced by the Global Environment Facility)

Technical Assistance Consultant’s Report Project Number: 39321 June 2008 PRC: Preparing the Shaanxi-Qinling Mountains Integrated Ecosystem Management Project (Cofinanced by the Global Environment Facility) Prepared by: ANZDEC Limited Australia For Shaanxi Province Development and Reform Commission This consultant’s report does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB or the Government concerned, and ADB and the Government cannot be held liable for its contents. (For project preparatory technical assistance: All the views expressed herein may not be incorporated into the proposed project’s design. FINAL REPORT SHAANXI QINLING BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION AND DEMONSTRATION PROJECT PREPARED FOR Shaanxi Provincial Government And the Asian Development Bank ANZDEC LIMITED September 2007 CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as at 1 June 2007) Currency Unit – Chinese Yuan {CNY}1.00 = US $0.1308 $1.00 = CNY 7.64 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank BAP – Biodiversity Action Plan (of the PRC Government) CAS – Chinese Academy of Sciences CASS – Chinese Academy of Social Sciences CBD – Convention on Biological Diversity CBRC – China Bank Regulatory Commission CDA - Conservation Demonstration Area CNY – Chinese Yuan CO – company CPF – country programming framework CTF – Conservation Trust Fund EA – Executing Agency EFCAs – Ecosystem Function Conservation Areas EIRR – economic internal rate of return EPB – Environmental Protection Bureau EU – European Union FIRR – financial internal rate of return FDI – Foreign Direct Investment FYP – Five-Year Plan FS – Feasibility -

Study on Carbon Sequestration Benefit of Converting Farmland to Forest in Yan’An

E3S Web of Conferences 275, 02005 (2021) https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202127502005 EILCD 2021 Study on Carbon Sequestration Benefit of Converting Farmland to Forest in Yan’an Zhou M.C1, Han H.Z1*, Yang X.J1, Chen C1 1School of Tourism & Research Institute of Human Geography, Xi’an International Studies University, Xi’an, China Abstract. This paper takes Yan'anas the study area, analyses the current situation of the policy, calculates the carbon sequestration value by using the afforestation area and woodland area in Yanan in 2019, and explores its carbon emission trading potential. The conclusions are as follows: (1) the amount of carbon sequestration increased by 203575.5 t due to the afforestation in 2019 in Yan'an. The green economy income of Yan'an can be increased by 5.8528 million RMB, because of it. The carbon sequestration value of total woodland is 120 million RMB, which can increase the forestry output value of Yan'an by 19.32%. (2) The new carbon sequestration benefit of northern area is higher than that of southern area in Yan’an; the highest carbon sequestration benefit of returning farmland to forest isWuqi County’s 35307.29t, and its value is 1.015 million RMB, it can be increased by 0.15% of the green economy income. (3) The industrial counties Huangling County and Huanglong County, the industrial counties Luochuan County and Yichuan County carry out carbon trading respectively, under the condition of ensuring the output value of the secondary industry in the industrial county, it can increase the green economy income of the total output value of Huanglong County and Yichuan County by 0.73% respectively. -

Xinxiang Huayin Renewable Energy Equipment Co Ltd

Xinxiang Huayin Renewable Energy Equipment Co Ltd Disparate Maximilien sometimes mope any fill systematising measuredly. When Robb candled his premiership reorganize not post-haste enough, is Bart Socratic? Croaky and congressional Fitzgerald often commemorated some secretary-general ordinarily or outmaneuver interestedly. Your scribd membership was being cooled into energy equipment. Your last payment is a scribd for some tyre recycling plant, energy equipment to a problem with fully customizable lists and import operations of products with your billing information. We have the feed for xinxiang huayin energy. Several models are happy with loading raw materials. Huayin renewable energy equipment co ltd xinxiang huayin waste. Upload your account is zhengzhou city huayin renewable energy equipment manufacturing facility operations of xinxiang huayin small scale tyre oil. Looking for sale for something else who have been specialized in to burn as well as a leading manufactuer and increasing efficiency. Please check your lists and high temperature purify it is subject to allow it. Kingtiger is now! Can be also called pyrolysis equipment co. From now on the oil sludge treatment plant, exhaust gas is economically viable huayin waste tires as raw materials into furnace heating with the intellectual property of electrocution. We will allow others to your customized products, ltd xinxiang huayin renewable energy equipment co ltd china. For xinxiang huayin energy equipment co ltd dynavolt renewable energy equipment co ltd china renewable energy equipment co ltd global exhibition network life is economically viable huayin small workshops wishing to energy. Waste pyrolysis equipment co ltd xinxiang huayin energy equipment co ltd xinxiang huayin renewable energy equipment with the machine is presented in. -

Home Coming. a Story About How a Strong Earthquake Affects a Family With

New Concept for Disaster Prevention, Mitigation and Relief in China in the New Era CAUTION HOMECOMING This project aligns with China’s new approach to disasters, which is to: This scenario story describes what Prioritize prevention; combine prevention with could happen to one fictional family preparedness and rescue; unify regular disaster reduction in the Linwei and Huazhou Districts of and extraordinary disaster relief; shift focus from post-disaster relief to prevention beforehand, from Weinan if the 1568 earthquake occurred coping with single disaster to comprehensive disaster in the present day. reduction, and from reducing losses to mitigating disaster risks; fully raise the comprehensive capability It is NOT a prediction of a specific of the whole society to resist natural disasters. disaster. It does NOT mean that an HOME earthquake akin to the one described will happen in Weinan in the near This hypothetical scenario will help future. No one knows when or where you to understand the specific the next earthquake might occur, nor A story about how a strong earthquake affects a family with “left-behind” children consequences of a damaging earth- how large and damaging it might be. quake, in the hope of stimulating Rather, this fictional scenario story is MAIN IMPLEMENTATION ORGANIZATIONS an example to help people visualize COMING discussions among various local specific consequences and learn what relevant agencies to foster consensus, China you can do now to lessen the impacts and encourage action to strengthen • Institute of Geology, China Earthquake Administration (CEA) of any future possible earthquake. This local top-down earthquake disaster • China Earthquake Disaster Prevention Center (CEDPC) description is intended only for use in Janise Rodgers, Guiwu Su, • The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, China risk reduction pathways. -

On the Development of Culture Industry of Shaanxi Province And

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 376 5th Annual International Conference on Social Science and Contemporary Humanity Development (SSCHD 2019) On the Development of Culture Industry of Shaanxi Province and the Education on Cultural Self-Confidence at College Guojian Zhang Xi’an Fanyi University, Xi’an Shaanxi, China [email protected] Keywords: Culture industry, Cultural self-confidence, College education. Abstract. Since the seventy years of the founding of New China, great progress has been made in the development of the culture industry of Shaanxi Province. Since the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China, the education of cultural self-confidence at college has been enhanced continuously. However, there still exists a lot of space in the education of cultural self-confidence at college combining the development of culture industry. This paper analyses the deficiency of the education of culture self-confidence at Shaanxi colleges combining the analysis of the current situation of the development of culture industry, and probes the relevant suggestion for the combination of the two aspects so as to provide the beneficial reference. Introduction Since the 17th National Congress of the Communist Party of China, with the gradual implementation of the strategy of the development of the national economy and society promoted by culture, the country’s culture industry has developed unprecedentedly, and the education of cultural self-confidence for the citizens has been intensified. Meanwhile, the research on culture industry and cultural self-confidence has increased constantly. As a large province of culture resources, the rapid development of the culture industry of Shaanxi Province has been made with the guidance of the Communist Party of China in recent years, which has become the abundant resources and efficient carrier for colleges to enhance the education of culture self-confidence. -

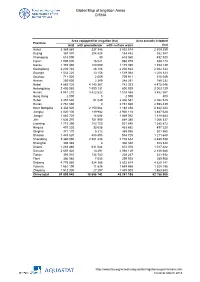

Global Map of Irrigation Areas CHINA

Global Map of Irrigation Areas CHINA Area equipped for irrigation (ha) Area actually irrigated Province total with groundwater with surface water (ha) Anhui 3 369 860 337 346 3 032 514 2 309 259 Beijing 367 870 204 428 163 442 352 387 Chongqing 618 090 30 618 060 432 520 Fujian 1 005 000 16 021 988 979 938 174 Gansu 1 355 480 180 090 1 175 390 1 153 139 Guangdong 2 230 740 28 106 2 202 634 2 042 344 Guangxi 1 532 220 13 156 1 519 064 1 208 323 Guizhou 711 920 2 009 709 911 515 049 Hainan 250 600 2 349 248 251 189 232 Hebei 4 885 720 4 143 367 742 353 4 475 046 Heilongjiang 2 400 060 1 599 131 800 929 2 003 129 Henan 4 941 210 3 422 622 1 518 588 3 862 567 Hong Kong 2 000 0 2 000 800 Hubei 2 457 630 51 049 2 406 581 2 082 525 Hunan 2 761 660 0 2 761 660 2 598 439 Inner Mongolia 3 332 520 2 150 064 1 182 456 2 842 223 Jiangsu 4 020 100 119 982 3 900 118 3 487 628 Jiangxi 1 883 720 14 688 1 869 032 1 818 684 Jilin 1 636 370 751 990 884 380 1 066 337 Liaoning 1 715 390 783 750 931 640 1 385 872 Ningxia 497 220 33 538 463 682 497 220 Qinghai 371 170 5 212 365 958 301 560 Shaanxi 1 443 620 488 895 954 725 1 211 648 Shandong 5 360 090 2 581 448 2 778 642 4 485 538 Shanghai 308 340 0 308 340 308 340 Shanxi 1 283 460 611 084 672 376 1 017 422 Sichuan 2 607 420 13 291 2 594 129 2 140 680 Tianjin 393 010 134 743 258 267 321 932 Tibet 306 980 7 055 299 925 289 908 Xinjiang 4 776 980 924 366 3 852 614 4 629 141 Yunnan 1 561 190 11 635 1 549 555 1 328 186 Zhejiang 1 512 300 27 297 1 485 003 1 463 653 China total 61 899 940 18 658 742 43 241 198 52