The Motor Theory of Social Cognition: a Critique Pierre Jacob, Marc Jeannerod

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mirror Neuron System and Social Cognition Spring Quarter 2017 Tuth 11:00 - 12:20 Pm CSB 005

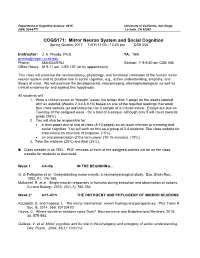

Department of Cognitive Science 0515 University of California, San Diego (858) 534-6771 La Jolla, CA 92093 COGS171: Mirror Neuron System and Social Cognition Spring Quarter 2017 TuTH 11:00 - 12:20 pm CSB 005 Instructor: J. A. Pineda, Ph.D. TA: TBN [email protected] Phone: 858-534-9754 SeCtion: F 9-9:50 am CSB 005 OffiCe Hours: M 9-11 am, CSB 107 (or by appointment) This class will examine the neuroanatomy, physiology, and funCtional Correlates of the human mirror neuron system and its putative role in soCial Cognition, e.g., aCtion understanding, empathy, and theory of mind. We will examine the developmental, neuroimaging, electrophysiologiCal, as well as clinical evidence for and against this hypothesis. All students will: 1. Write a CritiCal review or “thought” essay (no longer than 1 page) on the weeks labeled with an asterisk (Weeks 2,3,4,6,8,10) based on one of the required readings that week. See Class website (or ask instruCtor) for a sample of a CritiCal review. Essays are due on Tuesday of the assigned week - for a total of 6 essays, although only 5 will count towards grade (25%). 2. You will also be responsible for: • a term paper due at end of class (8-10 pages) on an issue relevant to mirroring and social cognition. You will work on this as a group of 3-4 students. See Class website for instruCtions on structure of proposal. (15%) • an oral presentation of the term paper (10-15 minutes). (10%) 3. Take the midterm (25%) and final (25%). -

A Revised Computational Neuroanatomy for Motor Control

This is the author’s final version; this article has been accepted for publication in the Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience 1 A Revised Computational Neuroanatomy for Motor Control 2 Shlomi Haar1, Opher Donchin2,3 3 1. Department of BioEngineering, Imperial College London, UK 4 2. Department of Biomedical Engineering, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Israel 5 3. Zlotowski Center for Neuroscience, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Israel 6 7 Corresponding author: Shlomi Haar ([email protected]) 8 Imperial College London, London, SW7 2AZ, UK 9 10 Acknowledgements: We would like to thank Ilan Dinstein, Liad Mudrik, Daniel Glaser, Alex Gail, and 11 Reza Shadmehr for helpful discussions about the manuscript. Shlomi Haar is supported by the Royal 12 Society – Kohn International Fellowship (NF170650). Work on this review was partially supported by 13 DFG grant TI-239/16-1. 14 15 Abstract 16 We discuss a new framework for understanding the structure of motor control. Our approach 17 integrates existing models of motor control with the reality of hierarchical cortical processing and the 18 parallel segregated loops that characterize cortical-subcortical connections. We also incorporate the recent 19 claim that cortex functions via predictive representation and optimal information utilization. Our 20 framework assumes each cortical area engaged in motor control generates a predictive model of a different 21 aspect of motor behavior. In maintaining these predictive models, each area interacts with a different part 22 of the cerebellum and basal ganglia. These subcortical areas are thus engaged in domain appropriate 23 system identification and optimization. This refocuses the question of division of function among different 24 cortical areas. -

Empathy, Mirror Neurons and SYNC

Mind Soc (2016) 15:1–25 DOI 10.1007/s11299-014-0160-x Empathy, mirror neurons and SYNC Ryszard Praszkier Received: 5 March 2014 / Accepted: 25 November 2014 / Published online: 14 December 2014 Ó The Author(s) 2014. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract This article explains how people synchronize their thoughts through empathetic relationships and points out the elementary neuronal mechanisms orchestrating this process. The many dimensions of empathy are discussed, as is the manner by which empathy affects health and disorders. A case study of teaching children empathy, with positive results, is presented. Mirror neurons, the recently discovered mechanism underlying empathy, are characterized, followed by a theory of brain-to-brain coupling. This neuro-tuning, seen as a kind of synchronization (SYNC) between brains and between individuals, takes various forms, including frequency aspects of language use and the understanding that develops regardless of the difference in spoken tongues. Going beyond individual- to-individual empathy and SYNC, the article explores the phenomenon of syn- chronization in groups and points out how synchronization increases group cooperation and performance. Keywords Empathy Á Mirror neurons Á Synchronization Á Social SYNC Á Embodied simulation Á Neuro-synchronization 1 Introduction We sometimes feel as if we just resonate with something or someone, and this feeling seems far beyond mere intellectual cognition. It happens in various situations, for example while watching a movie or connecting with people or groups. What is the mechanism of this ‘‘resonance’’? Let’s take the example of watching and feeling a film, as movies can affect us deeply, far more than we might realize at the time. -

Motor Control: a Sense of Movement

RESEARCH HIGHLIGHTS MOTOR CONTROL A sense of movement Neuroscience textbooks tell us that with a shorter latency after S1 stimu- whisker protraction, and that M1retract the motor cortex controls move- lation than after M1 stimulation. only induces whisker retraction ment. But now, Carl Petersen and Thus, S1 and M1 are both involved in indirectly, through S1 activation. colleagues show that sensory cortex whisker motor and sensory process- By mapping the neural pathways may have an equally important role ing. The M1 area that induced C2 involved in C2 whisker retraction in motor control. retraction was termed M1retract; a and protraction, the authors found The authors showed that a single, more medial M1 region that induced that M1C2 and S1C2 have reciprocal brief deflection of the C2 whisker C2 protraction under microstimula- connections and project to adjacent induced activity in the correspond- tion was termed M1protract. regions in subcortical areas. In the ing barrel column of the primary The authors next investigated the brain stem, this includes the reticular somatosensory cortex (S1), followed functional relevance of this finding. formation as a projection area of M1, by a response in a small area in the By attaching metal particles to the C2 and the spinal trigeminal nuclei as primary motor cortex (M1). Direct whisker and applying a pulsed mag- a projection area of S1. Both areas microstimulation or optogenetic netic field, the authors could evoke project to the facial nucleus, which stimulation of either area induced C2 whisker deflections. The whisker contains whisker motor neurons. a brief retraction of the C2 whisker, retracted in response to this stimulus, Indeed, direct electrical stimula- and this response was abolished when tion of the reticular formation and S1 was inactivated — but not spinal trigeminal nuclei induced when M1 was inactivated — with whisker protraction and retraction, tetrodoxin (TTX). -

Motor Control in the Brain

Motor Control in the Brain Travis DeWolf School of Computer Science University of Waterloo Waterloo, ON Canada December 19, 2008 Abstract There has been much progress in the development of a model of motor control in the brain in the last decade; from the improved method for mathematically extracting the predicted movement direction from a population of neurons to the application of optimal control theory to motor control models, much work has been done to further our understanding of this area. In this paper recent literature is reviewed and the direction of future research is examined. 1 Introduction In the last decade there has been a push from investigating the coordinate system used in the brain, which has been the focus of research since the 1970s, back toward using reductionist experiment techniques and developing more encompassing models of motor control in the brain[28]. Optimal control theory applied to motor control in the brain has also recently started being explored as a framework for models. This has lead to research into the underlying biology of the implementations of internal models of movement and reinforcement learning reward systems in the brain[32]. In addition to this, with the discovery of motor primitives[24], which are often referred to as the `building blocks of movement', many of the ideas about neural activity carried out in the motor cortex need be reworked. The analysis techniques employed by researchers have been improved and of course the computing power available has increased enormously, and these developments have in turn opened the door to the need for further mathematical technique developments for accurate movement analysis and prediction. -

1 the Development of Empathy: How, When, and Why Nicole M. Mcdonald & Daniel S. Messinger University of Miami Department Of

1 The Development of Empathy: How, When, and Why Nicole M. McDonald & Daniel S. Messinger University of Miami Department of Psychology 5665 Ponce de Leon Dr. Coral Gables, FL 33146, USA 2 Empathy is a potential psychological motivator for helping others in distress. Empathy can be defined as the ability to feel or imagine another person’s emotional experience. The ability to empathize is an important part of social and emotional development, affecting an individual’s behavior toward others and the quality of social relationships. In this chapter, we begin by describing the development of empathy in children as they move toward becoming empathic adults. We then discuss biological and environmental processes that facilitate the development of empathy. Next, we discuss important social outcomes associated with empathic ability. Finally, we describe atypical empathy development, exploring the disorders of autism and psychopathy in an attempt to learn about the consequences of not having an intact ability to empathize. Development of Empathy in Children Early theorists suggested that young children were too egocentric or otherwise not cognitively able to experience empathy (Freud 1958; Piaget 1965). However, a multitude of studies have provided evidence that very young children are, in fact, capable of displaying a variety of rather sophisticated empathy related behaviors (Zahn-Waxler et al. 1979; Zahn-Waxler et al. 1992a; Zahn-Waxler et al. 1992b). Measuring constructs such as empathy in very young children does involve special challenges because of their limited verbal expressiveness. Nevertheless, young children also present a special opportunity to measure constructs such as empathy behaviorally, with less interference from concepts such as social desirability or skepticism. -

Sensory Change Following Motor Learning

A. M. Green, C. E. Chapman, J. F. Kalaska and F. Lepore (Eds.) Progress in Brain Research, Vol. 191 ISSN: 0079-6123 Copyright Ó 2011 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. CHAPTER 2 Sensory change following motor learning { k { { Andrew A. G. Mattar , Sazzad M. Nasir , Mohammad Darainy , and { } David J. Ostry , ,* { Department of Psychology, McGill University, Montréal, Québec, Canada { Shahed University, Tehran, Iran } Haskins Laboratories, New Haven, Connecticut, USA k The Roxelyn and Richard Pepper Department of Communication Sciences and Disorders, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois, USA Abstract: Here we describe two studies linking perceptual change with motor learning. In the first, we document persistent changes in somatosensory perception that occur following force field learning. Subjects learned to control a robotic device that applied forces to the hand during arm movements. This led to a change in the sensed position of the limb that lasted at least 24 h. Control experiments revealed that the sensory change depended on motor learning. In the second study, we describe changes in the perception of speech sounds that occur following speech motor learning. Subjects adapted control of speech movements to compensate for loads applied to the jaw by a robot. Perception of speech sounds was measured before and after motor learning. Adapted subjects showed a consistent shift in perception. In contrast, no consistent shift was seen in control subjects and subjects that did not adapt to the load. These studies suggest that motor learning changes both sensory and motor function. Keywords: motor learning; sensory plasticity; arm movements; proprioception; speech motor control; auditory perception. Introduction the human motor system and, likewise, to skill acquisition in the adult nervous system. -

Motor Control Paper“ for Our Common Script - IPNFA - Nicola Fischer, Carsten Schaefer „Well-Fed-Version“

suggestion for a „Motor Control Paper“ for our common script - IPNFA - Nicola Fischer, Carsten Schaefer „well-fed-version“ _______________________________________ Motor Control _______________________________________ 1. Definition and Contributions of Motor Control 2. Postural control 3. Activities 1. Definitions and Contributions Ø Definition of Motor Control “Motor control is defined as the ability to regulate or direct the mechanisms essential to movement.” (Shumway-Cook & Woollacott 2011, p.4; Horak et al 1997) Relevant questions are: - “How does the central nervous system (CNS) organize the many individual muscles and joints into coordinated functional movements? (Bernstein 1967; Shumway-Cook & Woollacott 2011; Magill 2003; Schmidt & Lee 2011) - How is sensory information from the environment and the body used to select and control movement? - What is the best way to study movement, and how can movement problems be quantified in patients with motor control problems?” (Shumway-Cook & Woollacott 2011, p.4) “Movement emerges from interactions between the individual, the task and the environment.” (Shumway-Cook & Woollacott 2011, p.5) figure 1: adapted from Shumway-Cook (Shumway-Cook & Woollacott 2011) Ø Theories of Motor Control § Reflex Theory e.g. Sir. Ch. Sherrington (Sherrington 1947) § Hierarchical Theory e.g. Rudolf Magnus, Arnold Gesell § Motor Programming Theory e.g. Karl Lashley (Fitch & Martins 2014) Nicolai Bernstein … as a base for the Systems Theory (Bernstein 1967) § Systems Theory / Dynamic Action Theory / Dynamic Pattern Theory - self organizing systems e.g. J.A. Scott Kelso, Viktor Jirsa (Jirsa & Kelso 2004) § Ecological Theory e.g. James Gibson (Gibson 1983) Ø Sensory Contributions to Motor Control For the closed-loop control system, sensory (or afferent) information is necessary to regulate our suggestion for a „Motor Control Paper“ for our common script - IPNFA - Nicola Fischer, Carsten Schaefer „well-fed-version“ movements (Adams 1971; Schmidt & Lee 2011). -

Visual Recognition of Words Learned with Gestures Induces Motor

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Visual recognition of words learned with gestures induces motor resonance in the forearm muscles Claudia Repetto1*, Brian Mathias2,3, Otto Weichselbaum4 & Manuela Macedonia4,5,6 According to theories of Embodied Cognition, memory for words is related to sensorimotor experiences collected during learning. At a neural level, words encoded with self-performed gestures are represented in distributed sensorimotor networks that resonate during word recognition. Here, we ask whether muscles involved in gesture execution also resonate during word recognition. Native German speakers encoded words by reading them (baseline condition) or by reading them in tandem with picture observation, gesture observation, or gesture observation and execution. Surface electromyogram (EMG) activity from both arms was recorded during the word recognition task and responses were detected using eye-tracking. The recognition of words encoded with self-performed gestures coincided with an increase in arm muscle EMG activity compared to the recognition of words learned under other conditions. This fnding suggests that sensorimotor networks resonate into the periphery and provides new evidence for a strongly embodied view of recognition memory. Traditional perspectives in cognitive science describe human behaviour as mediated by cognitive representations1. Such representations have been defned as mental structures that encode, store and process information arising from sensory-motor systems 2. According to these perspectives, information provided to perceptual systems about the environment is incomplete. As a result, the brain has the essential role of transforming this information into cognitive representations, which enable rapid and accurate behaviours. In recent years, embodied approaches have claimed that perception, action and the environment jointly contribute to cognitive processes3,4, highlighting a change in our understanding of the role of the body in cognition. -

Reading Action Word Affects the Visual Perception of Biological Motion Christel Bidet-Ildei, Laurent Sparrow, Yann Coello

Reading action word affects the visual perception of biological motion Christel Bidet-Ildei, Laurent Sparrow, Yann Coello To cite this version: Christel Bidet-Ildei, Laurent Sparrow, Yann Coello. Reading action word affects the visual perception of biological motion. Acta Psychologica, Elsevier, 2011, 137 (3), pp.330 - 334. 10.1016/j.actpsy.2011.04.001. hal-01773532 HAL Id: hal-01773532 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01773532 Submitted on 17 Sep 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Reading action word affects the visual perception of biological motion Christel Bidet-Ildei 1,2 , Laurent Sparrow 1, Yann Coello 1 1 URECA (EA 1059), University of Lille-Nord de France, 2 CeRCA, UMR-CNRS 6234, University of Poitiers. Corresponding author: Pr Yann Coello. Email: [email protected] Running title: Biological motion perception Keywords: Perception; Vision; Biological motion; Motor cognition, Language; Priming; Point-light display. Mailing Address: Pr. Yann COELLO URECA Université Charles De Gaulle – Lille3 BP 60149 59653 Villeneuve d'Ascq cedex, France Tel: +33.3.20.41.64.46 Fax: +33.3.20.41.60.32 Email: [email protected] 1 Abstract In the present study, we investigate whether reading an action-word can influence subsequent visual perception of biological motion. -

The Perception for Action Control Theory (PACT): a Perceptuo-Motor Theory of Speech Perception Jean-Luc Schwartz, Anahita Basirat, Lucie Ménard, Marc Sato

The Perception for Action Control Theory (PACT): a perceptuo-motor theory of speech perception Jean-Luc Schwartz, Anahita Basirat, Lucie Ménard, Marc Sato To cite this version: Jean-Luc Schwartz, Anahita Basirat, Lucie Ménard, Marc Sato. The Perception for Action Control Theory (PACT): a perceptuo-motor theory of speech perception. Journal of Neurolinguistics, Elsevier, 2012, 25 (5), pp.336-354. 10.1016/j.jneuroling.2009.12.004. hal-00442367 HAL Id: hal-00442367 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00442367 Submitted on 21 Dec 2009 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. The Perception for Action Control Theory (PACT): a perceptuo-motor theory of speech perception Jean-Luc Schwartz (1), Anahita Basirat (1), Lucie Ménard (2), Marc Sato (1) (1) GIPSA-Lab, Speech and Cognition Department (ICP), UMR 5216 CNRS – Grenoble University, France (2) Laboratoire de Phonétique, UQAM / CRLMB, Montreal, Canada Abstract It is an old-standing debate in the field of speech communication to determine whether speech perception involves auditory or multisensory representations and processing, independently on any procedural knowledge about the production of speech units or on the contrary if it is based on a recoding of the sensory input in terms of articulatory gestures, as posited in the Motor Theory of Speech Perception. -

The Social-Emotional Processing Stream: Five Core Constructs and Their Translational Potential for Schizophrenia and Beyond Kevin N

The Social-Emotional Processing Stream: Five Core Constructs and Their Translational Potential for Schizophrenia and Beyond Kevin N. Ochsner Background: Cognitive neuroscience approaches to translational research have made great strides toward understanding basic mecha- nisms of dysfunction and their relation to cognitive deficits, such as thought disorder in schizophrenia. The recent emergence of Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience has paved the way for similar progress to be made in explaining the mechanisms underlying the social and emotional dysfunctions (i.e., negative symptoms) of schizophrenia and that characterize virtually all DSM Axis I and II disorders more broadly. Methods: This article aims to provide a roadmap for this work by distilling from the emerging literature on the neural bases of social and emotional abilities a set of key constructs that can be used to generate questions about the mechanisms of clinical dysfunction in general and schizophrenia in particular. Results: To achieve these aims, the first part of this article sketches a framework of five constructs that comprise a social-emotional processing stream. The second part considers how future basic research might flesh out this framework and translational work might relate it to schizophrenia and other clinical populations. Conclusions: Although the review suggests there is more basic research needed for each construct, two in particular—one involving the bottom-up recognition of social and emotional cues, the second involving the use of top-down processes to draw mental state inferences— are most ready for translational work. Key Words: Amygdala, cingulate cortex, cognitive neuroscience, and methods this new work employs, it can be difficult to figure emotion, prefrontal cortex, schizophrenia, social cognition, transla- out how diverse pieces of data fit together into core neurofunc- tional research tional constructs.