1 the Development of Empathy: How, When, and Why Nicole M. Mcdonald & Daniel S. Messinger University of Miami Department Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Interaction of Social Affect and Cognition: Empathy, Compassion and Theory of Mind

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect On the interaction of social affect and cognition: empathy, compassion and theory of mind 1 1,2 1 Katrin Preckel , Philipp Kanske and Tania Singer Empathy, compassion and Theory of Mind (ToM) are central which may be detrimental to the observer and to others topics in social psychology and neuroscience. While empathy and compassion, on the other hand, which is a feeling of enables the sharing of others’ emotions and may result in warmth and concern for the other. We conclude with a empathic distress, a maladaptive form of empathic resonance, concise summary and an opinion statement. or compassion, a feeling of warmth and concern for others, ToM provides cognitive understanding of someone else’s Defining and neurally characterizing empathy, thoughts or intentions. These socio-affective and socio- compassion and Theory of Mind cognitive routes to understanding others are subserved by Empathy describes the process of sharing feelings, that is, separable, independent brain networks. Nonetheless they are resonating with someone else’s feelings, regardless of jointly required in many complex social situations. A process valence (positive/negative), but with the explicit knowl- that is critical for both, empathy and ToM, is self-other edge that the other person is the origin of this emotion [1]. distinction, which is implemented in different temporoparietal This socio-affective process results from neural network brain regions. Thus, adaptive social behavior is a result of activations that resemble those activations observed dynamic interplay of socio-affective and socio-cognitive when the same emotion is experienced first-hand (shared processes. -

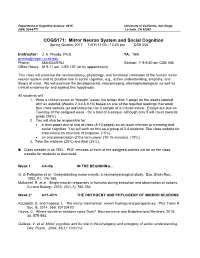

Mirror Neuron System and Social Cognition Spring Quarter 2017 Tuth 11:00 - 12:20 Pm CSB 005

Department of Cognitive Science 0515 University of California, San Diego (858) 534-6771 La Jolla, CA 92093 COGS171: Mirror Neuron System and Social Cognition Spring Quarter 2017 TuTH 11:00 - 12:20 pm CSB 005 Instructor: J. A. Pineda, Ph.D. TA: TBN [email protected] Phone: 858-534-9754 SeCtion: F 9-9:50 am CSB 005 OffiCe Hours: M 9-11 am, CSB 107 (or by appointment) This class will examine the neuroanatomy, physiology, and funCtional Correlates of the human mirror neuron system and its putative role in soCial Cognition, e.g., aCtion understanding, empathy, and theory of mind. We will examine the developmental, neuroimaging, electrophysiologiCal, as well as clinical evidence for and against this hypothesis. All students will: 1. Write a CritiCal review or “thought” essay (no longer than 1 page) on the weeks labeled with an asterisk (Weeks 2,3,4,6,8,10) based on one of the required readings that week. See Class website (or ask instruCtor) for a sample of a CritiCal review. Essays are due on Tuesday of the assigned week - for a total of 6 essays, although only 5 will count towards grade (25%). 2. You will also be responsible for: • a term paper due at end of class (8-10 pages) on an issue relevant to mirroring and social cognition. You will work on this as a group of 3-4 students. See Class website for instruCtions on structure of proposal. (15%) • an oral presentation of the term paper (10-15 minutes). (10%) 3. Take the midterm (25%) and final (25%). -

The Influence of Emotional States on Short-Term Memory Retention by Using Electroencephalography (EEG) Measurements: a Case Study

The Influence of Emotional States on Short-term Memory Retention by using Electroencephalography (EEG) Measurements: A Case Study Ioana A. Badara1, Shobhitha Sarab2, Abhilash Medisetty2, Allen P. Cook1, Joyce Cook1 and Buket D. Barkana2 1School of Education, University of Bridgeport, 221 University Ave., Bridgeport, Connecticut, 06604, U.S.A. 2Department of Electrical Engineering, University of Bridgeport, 221 University Ave., Bridgeport, Connecticut, 06604, U.S.A. Keywords: Memory, Learning, Emotions, EEG, ERP, Neuroscience, Education. Abstract: This study explored how emotions can impact short-term memory retention, and thus the process of learning, by analyzing five mental tasks. EEG measurements were used to explore the effects of three emotional states (e.g., neutral, positive, and negative states) on memory retention. The ANT Neuro system with 625Hz sampling frequency was used for EEG recordings. A public-domain library with emotion-annotated images was used to evoke the three emotional states in study participants. EEG recordings were performed while each participant was asked to memorize a list of words and numbers, followed by exposure to images from the library corresponding to each of the three emotional states, and recall of the words and numbers from the list. The ASA software and EEGLab were utilized for the analysis of the data in five EEG bands, which were Alpha, Beta, Delta, Gamma, and Theta. The frequency of recalled event-related words and numbers after emotion arousal were found to be significantly different when compared to those following exposure to neutral emotions. The highest average energy for all tasks was observed in the Delta activity. Alpha, Beta, and Gamma activities were found to be slightly higher during the recall after positive emotion arousal. -

In Praise of Empathy: the Glue That Holds Caring Communities Together in a Fractured World

Canadian Journal of Family and Youth, 11(1), 2019, pp. 234-291 ISSN 1718-9748© University of Alberta http://ejournals,library,ualberta.ca/index/php/cjfy In Praise of Empathy: The Glue that holds Caring Communities Together in a Fractured World. Irene G. Wilkinson Abstract In a tumultuous world where populism is on the rise as the result of an enraged, disenchanted, misguided and susceptible populace, empathy, one of the most vital of our moral virtues, is in serious jeopardy. Fear, prejudice and the rise of the extreme right has provoked a number of nay- sayers to draw our attention to what they believe to be the darker side of empathy, its biases and its vulnerability to subversion. This paper examines empathy, what it is, how it feels, the neural and environmental basis for its development, our moral obligation to nurture it in our children and how it may be induced in the case of empathy deficiencies. It considers the influences of gender and hormones on the expression of empathy and its relationship with sympathy and compassion. Also discussed are the properties of empathy as a motivational, socioemotional mechanism, that evokes kindness, caring, compassion and understanding in each of us, and its potential to neutralize the negativism, cruelty, violence and aggression, so prevalent in the world today. Although her formal qualifications are in biomedical science (her thesis on methods for demonstrating changes in the lining cells of the human larynx won her a Fellowship of the Institute of Biomedical Sciences in 1973), in addition to cancer research, Irene Gregory Wilkinson has worked for much of her life in fine and performing arts, broadcasting and in educational and social skills support for children at risk. -

Anger in Negotiations: a Review of Causes, Effects, and Unanswered Questions David A

Negotiation and Conflict Management Research Anger in Negotiations: A Review of Causes, Effects, and Unanswered Questions David A. Hunsaker Department of Management, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, U.S.A. Keywords Abstract anger, negotiation, emotion, attribution. This article reviews the literature on the emotion of anger in the negotia- tion context. I discuss the known antecedents of anger in negotiation, as Correspondence well as its positive and negative inter- and intrapersonal effects. I pay par- David Hunsaker, David Eccles ticular attention to the apparent disagreements within the literature con- School of Business, Spencer Fox cerning the benefits and drawbacks of using anger to gain advantage in Eccles Business Building, negotiations and employ Attribution Theory as a unifying mechanism to University of Utah, 1655 East Campus Center Drive, Salt Lake help explain these diverse findings. I call attention to the weaknesses evi- City, UT 84112, U.S.A.; e-mail: dent in current research questions and methodologies and end with sug- david.hunsaker@eccles. gestions for future research in this important area. utah.edu. What role does anger play in the negotiation context? Can this emotion be harnessed and manipulated to increase negotiating power and improve negotiation outcomes, or does it have inevitable downsides? The purpose of this article is to review the work of scholars that have focused on the emotion of anger within the negotiation context. I begin by offering some background on the field of research to be reviewed. I then explain why Attri- bution Theory is particularly helpful in making sense of diverse findings in the field. -

The Neural Pathways, Development and Functions of Empathy

EVIDENCE-BASED RESEARCH ON CHARITABLE GIVING SPI FUNDED The Neural Pathways, Development and Functions of Empathy Jean Decety University of Chicago Working Paper No.: 125- SPI April 2015 Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect The neural pathways, development and functions of empathy Jean Decety Empathy reflects an innate ability to perceive and be sensitive to and relative intensity without confusion between self and the emotional states of others coupled with a motivation to care other; secondly, empathic concern, which corresponds to for their wellbeing. It has evolved in the context of parental care the motivation to caring for another’s welfare; and thirdly, for offspring as well as within kinship. Current work perspective taking (or cognitive empathy), the ability to demonstrates that empathy is underpinned by circuits consciously put oneself into the mind of another and connecting the brainstem, amygdala, basal ganglia, anterior understand what that person is thinking or feeling. cingulate cortex, insula and orbitofrontal cortex, which are conserved across many species. Empirical studies document Proximate mechanisms of empathy that empathetic reactions emerge early in life, and that they are Each of these emotional, motivational, and cognitive not automatic. Rather they are heavily influenced and modulated facets of empathy relies on specific mechanisms, which by interpersonal and contextual factors, which impact behavior reflect evolved abilities of humans and their ancestors to and cognitions. However, the mechanisms supporting empathy detect and respond to social signals necessary for surviv- are also flexible and amenable to behavioral interventions that ing, reproducing, and maintaining well-being. While it is can promote caring beyond kin and kith. -

Empathy, Mirror Neurons and SYNC

Mind Soc (2016) 15:1–25 DOI 10.1007/s11299-014-0160-x Empathy, mirror neurons and SYNC Ryszard Praszkier Received: 5 March 2014 / Accepted: 25 November 2014 / Published online: 14 December 2014 Ó The Author(s) 2014. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract This article explains how people synchronize their thoughts through empathetic relationships and points out the elementary neuronal mechanisms orchestrating this process. The many dimensions of empathy are discussed, as is the manner by which empathy affects health and disorders. A case study of teaching children empathy, with positive results, is presented. Mirror neurons, the recently discovered mechanism underlying empathy, are characterized, followed by a theory of brain-to-brain coupling. This neuro-tuning, seen as a kind of synchronization (SYNC) between brains and between individuals, takes various forms, including frequency aspects of language use and the understanding that develops regardless of the difference in spoken tongues. Going beyond individual- to-individual empathy and SYNC, the article explores the phenomenon of syn- chronization in groups and points out how synchronization increases group cooperation and performance. Keywords Empathy Á Mirror neurons Á Synchronization Á Social SYNC Á Embodied simulation Á Neuro-synchronization 1 Introduction We sometimes feel as if we just resonate with something or someone, and this feeling seems far beyond mere intellectual cognition. It happens in various situations, for example while watching a movie or connecting with people or groups. What is the mechanism of this ‘‘resonance’’? Let’s take the example of watching and feeling a film, as movies can affect us deeply, far more than we might realize at the time. -

Empathic Concern Is Part of a More General Communal Emotion

1 Empathic Concern is Part of A More General Communal Emotion Janis H. Zickfeld1*, Thomas W. Schubert12, Beate Seibt12, Alan P. Fiske3 1Department of Psychology, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway. 2Instituto Universitário de Lisboa (ISCTE-IUL), Lisboa, Portugal. 3Department of Anthropology, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA. In press at Frontiers. This paper is not the copy of record and may not exactly replicate the authoritative document published in Frontiers. *Correspondence: Janis H. Zickfeld [email protected] 2 Abstract Seeing someone in need may evoke a particular kind of closeness that has been conceptualized as sympathy or empathic concern (which is distinct from other empathy constructs). In other contexts, when people suddenly feel close to others, or observe others suddenly feeling closer to each other, this sudden closeness tends to evoke an emotion often labeled in vernacular English as being moved, touched, or heart-warming feelings. Recent theory and empirical work indicates that this is a distinct emotion; the construct is named kama muta. Is empathic concern for people in need simply an expression of the much broader tendency to respond with kama muta to all kinds of situations that afford closeness, such as reunions, kindness, and expressions of love? Across 16 studies sampling 2918 participants, we explored whether empathic concern is associated with kama muta. Meta-analyzing the association between ratings of state being moved and trait empathic concern revealed an effect size of, r(3631) = .35 [95% CI: .29, .41]. In addition, trait empathic concern was also associated with self-reports of the three sensations that have been shown to be reliably indicative of kama muta: weeping, chills, and bodily feelings of warmth. -

Strategic Empathy As a Tool of Statecraft

Strategic Empathy as a Tool of Statecraft John Dale Grover Published October 2016 Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Empathy Defined ........................................................................................................................................ 4 Strategic Empathy as a Tool of Statecraft ................................................................................................ 7 International Relations Theory and Empathy ....................................................................................... 14 The Opening of China .............................................................................................................................. 24 American Policy in the Iraq War ............................................................................................................ 30 Conclusion ................................................................................................................................................. 35 Bibliography .............................................................................................................................................. 37 2 Introduction “If you know the enemy and know yourself, you need not fear the result of a hundred battles. If you know yourself but not the enemy, for every victory gained you will also suffer a defeat. If you know neither the enemy nor yourself, you will succumb -

Finding the Golden Mean: the Overuse, Underuse, and Optimal Use of Character Strengths

Counselling Psychology Quarterly ISSN: 0951-5070 (Print) 1469-3674 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ccpq20 Finding the golden mean: the overuse, underuse, and optimal use of character strengths Ryan M. Niemiec To cite this article: Ryan M. Niemiec (2019): Finding the golden mean: the overuse, underuse, and optimal use of character strengths, Counselling Psychology Quarterly, DOI: 10.1080/09515070.2019.1617674 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2019.1617674 Published online: 20 May 2019. Submit your article to this journal View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ccpq20 COUNSELLING PSYCHOLOGY QUARTERLY https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2019.1617674 ARTICLE Finding the golden mean: the overuse, underuse, and optimal use of character strengths Ryan M. Niemiec VIA Institute on Character, Cincinnati, OH, USA ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY The science of well-being has catalyzed a tremendous amount of Received 28 February 2019 research with no area more robust in application and impact than Accepted 8 May 2019 the science of character strengths. As the empirical links between KEYWORDS character strengths and positive outcomes rapidly grow, the research Character strengths; around strength imbalances and the use of strengths with problems strengths overuse; strengths and conflicts is nascent. The use of character strengths in understand- underuse; optimal use; ing and handling life suffering as well as emerging from it, is particularly second wave positive aligned within second wave positive psychology. Areas of particular psychology; golden mean promise include strengths overuse and strengths underuse, alongside its companion of strengths optimaluse.Thelatterisviewedasthe golden mean of character strengths which refers to the expression of the right combination of strengths, to the right degree, and in the right situation. -

“Trees Have a Soul Too!” Developing Empathy and Environmental Values in Early Childhood

The International Journal of Early Childhood Environmental Education, 5(1), p. 68 International Journal of Early Childhood Environmental Education Copyright © North American Association for Environmental Education ISSN: 2331-0464 (online) “Trees have a soul too!” Developing Empathy and Environmental Values in Early Childhood Loukia S. Lithoxoidou 77th Kindergarten School of Thessaloniki, Greece Alexandros D. Georgopoulos Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece Anastasia Th. Dimitriou Democritus University of Thrace, Alexandroupolis, Greece Sofia Ch. Xenitidou NOESIS Science Center and Technology Museum, Greece Submitted June 22, 2016; accepted April 17, 2017 ABSTRACT Coping with environmental crisis cannot but presuppose a change in the values adopted by modern man. Both ecocentric values associated with creating a caring relationship with nature, and the development of empathy, can become vehicles of transformation towards a society based on ecological principles. In connection with these issues, an Environmental Education program for preschoolers was designed and implemented in the classroom. The evaluation shows that preschool children can be interested in non-human beings, can feel the need to protect them, and ascribe them intrinsic value. Keywords: environmental values, empathy, preschool environmental education What accords Environmental Education its dynamic character - and marks its difference from environmental studies - is the dimension of critique, relating to the identity of the active citizen who - through studying and clarifying attitudes and values, rejects the prevailing standards, and who, by seeking alternative ways of being, modifies his actions accordingly, and consequently transforms society and the environment (Sterling, 1993). A special case of such a process involves the anthropocentrism - ecocentrism dichotomy and all the movements in between that have emerged over the last decades (Attfield, 2014). -

Individual Differences in Empathy Are Associated with Apathy-Motivation

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Individual diferences in empathy are associated with apathy- motivation Received: 1 August 2017 Patricia L. Lockwood 1,2, Yuen-Siang Ang 1,2,3, Masud Husain 1,2,3 & Molly J. Crockett1,4 Accepted: 24 November 2017 Empathy - the capacity to understand and resonate with the experiences of other people - is considered Published: xx xx xxxx an essential aspect of social cognition. However, although empathy is often thought to be automatic, recent theories have argued that there is a key role for motivation in modulating empathic experiences. Here we administered self-report measures of empathy and apathy-motivation to a large sample of healthy people (n = 378) to test whether people who are more empathic are also more motivated. We then sought to replicate our fndings in an independent sample (n = 198) that also completed a behavioural task to measure state afective empathy and emotion recognition. Cognitive empathy was associated with higher levels of motivation generally across behavioural, social and emotional domains. In contrast, afective empathy was associated with lower levels of behavioural motivation, but higher levels of emotional motivation. Factor analyses showed that empathy and apathy are distinct constructs, but that afective empathy and emotional motivation are underpinned by the same latent factor. These results have potentially important clinical applications for disorders associated with reduced empathy and motivation as well as the understanding of these processes in healthy people. Empathy – the capacity to understand and resonate with the experiences of other people – is considered essential for navigating meaningful social interactions and is closely linked to prosocial behaviour1–7.