Empathy, Mirror Neurons and SYNC

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mirror Neuron System and Social Cognition Spring Quarter 2017 Tuth 11:00 - 12:20 Pm CSB 005

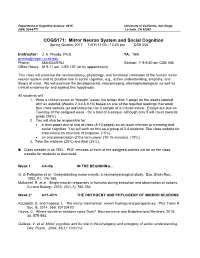

Department of Cognitive Science 0515 University of California, San Diego (858) 534-6771 La Jolla, CA 92093 COGS171: Mirror Neuron System and Social Cognition Spring Quarter 2017 TuTH 11:00 - 12:20 pm CSB 005 Instructor: J. A. Pineda, Ph.D. TA: TBN [email protected] Phone: 858-534-9754 SeCtion: F 9-9:50 am CSB 005 OffiCe Hours: M 9-11 am, CSB 107 (or by appointment) This class will examine the neuroanatomy, physiology, and funCtional Correlates of the human mirror neuron system and its putative role in soCial Cognition, e.g., aCtion understanding, empathy, and theory of mind. We will examine the developmental, neuroimaging, electrophysiologiCal, as well as clinical evidence for and against this hypothesis. All students will: 1. Write a CritiCal review or “thought” essay (no longer than 1 page) on the weeks labeled with an asterisk (Weeks 2,3,4,6,8,10) based on one of the required readings that week. See Class website (or ask instruCtor) for a sample of a CritiCal review. Essays are due on Tuesday of the assigned week - for a total of 6 essays, although only 5 will count towards grade (25%). 2. You will also be responsible for: • a term paper due at end of class (8-10 pages) on an issue relevant to mirroring and social cognition. You will work on this as a group of 3-4 students. See Class website for instruCtions on structure of proposal. (15%) • an oral presentation of the term paper (10-15 minutes). (10%) 3. Take the midterm (25%) and final (25%). -

The Mirror Neuron System: How Cognitive Functions Emerge from Motor Organization Leonardo Fogassi

The mirror neuron system: How cognitive functions emerge from motor organization Leonardo Fogassi To cite this version: Leonardo Fogassi. The mirror neuron system: How cognitive functions emerge from motor or- ganization. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, Elsevier, 2010, 77 (1), pp.66. 10.1016/j.jebo.2010.04.009. hal-00921186 HAL Id: hal-00921186 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00921186 Submitted on 20 Dec 2013 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Accepted Manuscript Title: The mirror neuron system: How cognitive functions emerge from motor organization Author: Leonardo Fogassi PII: S0167-2681(10)00177-0 DOI: doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2010.04.009 Reference: JEBO 2604 To appear in: Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization Received date: 26-7-2009 Revised date: 19-4-2010 Accepted date: 20-4-2010 Please cite this article as: Fogassi, L., The mirror neuron system: How cognitive functions emerge from motor organization, Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization (2010), doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2010.04.009 This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. -

University of Groningen Empathic Accuracy and Oxytocin After

University of Groningen Empathic accuracy and oxytocin after tryptophan depletion in adults at risk for depression Hogenelst, Koen; Schoevers, Robert A.; Kema, Ido; Sweep, Fred C G J; aan het Rot, Marije Published in: Psychopharmacology DOI: 10.1007/s00213-015-4093-9 IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2016 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Hogenelst, K., Schoevers, R. A., Kema, I. P., Sweep, F. C. G. J., & Aan Het Rot, M. (2016). Empathic accuracy and oxytocin after tryptophan depletion in adults at risk for depression. Psychopharmacology, 233(1), 111-120 . DOI: 10.1007/s00213-015-4093-9 Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 11-02-2018 Psychopharmacology (2016) 233:111–120 DOI 10.1007/s00213-015-4093-9 ORIGINAL INVESTIGATION Empathic accuracy and oxytocin after tryptophan depletion in adults at risk for depression Koen Hogenelst1,2 & Robert A. -

The Neural Components of Empathy: Predicting Daily Prosocial Behavior

doi:10.1093/scan/nss088 SCAN (2014) 9,39^ 47 The neural components of empathy: Predicting daily prosocial behavior Sylvia A. Morelli, Lian T. Rameson, and Matthew D. Lieberman Department of Psychology, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1563 Previous neuroimaging studies on empathy have not clearly identified neural systems that support the three components of empathy: affective con- gruence, perspective-taking, and prosocial motivation. These limitations stem from a focus on a single emotion per study, minimal variation in amount of social context provided, and lack of prosocial motivation assessment. In the current investigation, 32 participants completed a functional magnetic resonance imaging session assessing empathic responses to individuals experiencing painful, anxious, and happy events that varied in valence and amount of social context provided. They also completed a 14-day experience sampling survey that assessed real-world helping behaviors. The results demonstrate that empathy for positive and negative emotions selectively activates regions associated with positive and negative affect, respectively. Downloaded from In addition, the mirror system was more active during empathy for context-independent events (pain), whereas the mentalizing system was more active during empathy for context-dependent events (anxiety, happiness). Finally, the septal area, previously linked to prosocial motivation, was the only region that was commonly activated across empathy for pain, anxiety, and happiness. Septal activity during each of these empathic experiences was predictive of daily helping. These findings suggest that empathy has multiple input pathways, produces affect-congruent activations, and results in septally mediated prosocial motivation. http://scan.oxfordjournals.org/ Keywords: empathy; prosocial behavior; septal area INTRODUCTION neuroimaging studies of empathy, 30 focused on empathy for pain Human beings are intensely social creatures who have a need to belong (Fan et al., 2011). -

Critical Neuroscience

Choudhury_bindex.indd 391 7/22/2011 4:08:46 AM Critical Neuroscience Choudhury_ffirs.indd i 7/22/2011 4:37:11 AM Choudhury_ffirs.indd ii 7/22/2011 4:37:11 AM Critical Neuroscience A Handbook of the Social and Cultural Contexts of Neuroscience Edited by Suparna Choudhury and Jan Slaby A John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., Publication Choudhury_ffirs.indd iii 7/22/2011 4:37:11 AM This edition first published 2012 © 2012 Blackwell Publishing Ltd Blackwell Publishing was acquired by John Wiley & Sons in February 2007. Blackwell’s publishing program has been merged with Wiley’s global Scientific, Technical, and Medical business to form Wiley-Blackwell. Registered Office John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK Editorial Offices 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services, and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell. The right of Suparna Choudhury and Jan Slaby to be identified as the authors of the editorial material in this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. -

1 the Development of Empathy: How, When, and Why Nicole M. Mcdonald & Daniel S. Messinger University of Miami Department Of

1 The Development of Empathy: How, When, and Why Nicole M. McDonald & Daniel S. Messinger University of Miami Department of Psychology 5665 Ponce de Leon Dr. Coral Gables, FL 33146, USA 2 Empathy is a potential psychological motivator for helping others in distress. Empathy can be defined as the ability to feel or imagine another person’s emotional experience. The ability to empathize is an important part of social and emotional development, affecting an individual’s behavior toward others and the quality of social relationships. In this chapter, we begin by describing the development of empathy in children as they move toward becoming empathic adults. We then discuss biological and environmental processes that facilitate the development of empathy. Next, we discuss important social outcomes associated with empathic ability. Finally, we describe atypical empathy development, exploring the disorders of autism and psychopathy in an attempt to learn about the consequences of not having an intact ability to empathize. Development of Empathy in Children Early theorists suggested that young children were too egocentric or otherwise not cognitively able to experience empathy (Freud 1958; Piaget 1965). However, a multitude of studies have provided evidence that very young children are, in fact, capable of displaying a variety of rather sophisticated empathy related behaviors (Zahn-Waxler et al. 1979; Zahn-Waxler et al. 1992a; Zahn-Waxler et al. 1992b). Measuring constructs such as empathy in very young children does involve special challenges because of their limited verbal expressiveness. Nevertheless, young children also present a special opportunity to measure constructs such as empathy behaviorally, with less interference from concepts such as social desirability or skepticism. -

Mirror Neurons and Their Reflections

Open Access Library Journal Mirror Neurons and Their Reflections Mehmet Tugrul Cabioglu1, Sevgin Ozlem Iseri2 1Department of Physiology, Faculty of Medicine, Baskent University, Ankara, Turkey 2Department of Clinical Biochemistry, Faculty of Medicine, Hacettepe University, Ankara, Turkey Received 23 October 2015; accepted 7 November 2015; published 12 November 2015 Copyright © 2015 by authors and OALib. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Abstract Human mirror neuron system is believed to provide the basic mechanism for social cognition. Mirror neurons were first discovered in 1990s in the premotor area (F5) of macaque monkeys. Besides the premotor area, mirror neuron systems, having different functions depending on their locations, are found in various cortical areas. In addition, the importance of cingulate cortex in mother-infant relationship is clearly emphasized in the literature. Functional magnetic resonance imaging, electroencephalography, transcortical magnetic stimulation are the modalities used to evaluate the, activity of mirror neurons; for instance, mu wave suppression in electroencephalo- graphy recordings is considered as an evidence of mirror neuron activity. Mirror neurons have very important functions such as language processing, comprehension, learning, social interaction and empathy. For example, autistic individuals have less mirror neuron activity; therefore, it is thought that they have less ability of empathy. Responses of mirror neurons to object-directed and non-object directed actions are different and non-object directed action is required for the activa- tion of mirror neurons. Previous researchers find significantly more suppression during the ob- servation of object-directed movements as compared to mimed actions. -

The Neural Bases of Empathic Accuracy

The neural bases of empathic accuracy Jamil Zaki1, Jochen Weber, Niall Bolger, and Kevin Ochsner Department of Psychology, Columbia University, New York, NY 10027 Edited by Michael I. Posner, University of Oregon, Eugene, OR, and approved May 14, 2009 (received for review March 12, 2009) Theories of empathy suggest that an accurate understanding of remains unknown, because extant methods are unable to address another’s emotions should depend on affective, motor, and/or this question. To explore the neural bases of accurate interper- higher cognitive brain regions, but until recently no experimental sonal understanding, a method would need to indicate that method has been available to directly test these possibilities. Here, activation of a neural system predicts a match between perceiv- we present a functional imaging paradigm that allowed us to ers’ beliefs about targets’ internal states and the states targets address this issue. We found that empathically accurate, as com- report themselves to be experiencing (21). pared with inaccurate, judgments depended on (i) structures Instead, extant studies have probed neural activity while within the human mirror neuron system thought to be involved in perceivers passively view or experience actions and sensory shared sensorimotor representations, and (ii) regions implicated in states or make judgments about fictional targets whose internal mental state attribution, the superior temporal sulcus and medial states are implied in pictures or fictional vignettes. In either case, prefrontal cortex. These data demostrate that activity in these 2 comparisons between perceiver judgments and what targets sets of brain regions tracks with the accuracy of attributions made actually experienced cannot be made. -

Social Neuroscience and Psychopathology: Identifying the Relationship Between Neural Function, Social Cognition, and Social Beha

Hooker, C.I. (2014). Social Neuroscience and Psychopathology, Chapter to appear in Social Neuroscience: Mind, Brain, and Society Social Neuroscience and Psychopathology: Identifying the relationship between neural function, social cognition, and social behavior Christine I. Hooker, Ph.D. ***************************** Learning Goals: 1. Identify main categories of social and emotional processing and primary neural regions supporting each process. 2. Identify main methodological challenges of research on the neural basis of social behavior in psychopathology and strategies for addressing these challenges. 3. Identify how research in the three social processes discussed in detail – social learning, self-regulation, and theory of mind – inform our understanding of psychopathology. Summary Points: 1. Several psychiatric disorders, such as schizophrenia and autism, are characterized by social functioning deficits, but there are few interventions that effectively address social problems. 2. Treatment development is hindered by research challenges that limit knowledge about the neural systems that support social behavior, how those neural systems and associated social behaviors are compromised in psychopathology, and how the social environment influences neural function, social behavior, and symptoms of psychopathology. 3. These research challenges can be addressed by tailoring experimental design to optimize sensitivity of both neural and social measures as well as reduce confounds associated with psychopathology. 4. Investigations on the neural mechanisms of social learning, self-regulation, and Theory of Mind provide examples of methodological approaches that can inform our understanding of psychopathology. 5. High-levels of neuroticism, which is a vulnerability for anxiety disorders, is related to hypersensitivity of the amygdala during social fear learning. 6. High-levels of social anhedonia, which is a vulnerability for schizophrenia- spectrum disorders, is related to reduced lateral prefrontal cortex (LPFC) activity 1 Hooker, C.I. -

Mapping the Cerebral Subject in Contemporary Culture DOI: 10.3395/Reciis.V1i2.90En

[www.reciis.cict.fiocruz.br] ISSN 1981-6286 Researches in Progress Mapping the cerebral subject in contemporary culture DOI: 10.3395/reciis.v1i2.90en Francisco Fernando Vidal Max Planck Institute for the Ortega History of Science, Berlin, Instituto de Medicina Social Germany da Universidade do Estado [email protected] do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil [email protected] Abstract The research reported here aims at mapping the “cerebral subject” in contemporary society. The term “cerebral subject” refers to an anthropological figure that embodies the belief that human beings are essentially reducible to their brains. Our focus is on the discourses, images and practices that might globally be designated as “neurocul- ture.” From public policy to the arts, from the neurosciences to theology, humans are often treated as reducible to their brains. The new discipline of neuroethics is eminently symptomatic of such a situation; other examples can be drawn from science fiction in writing and film; from practices such as “neurobics” or cerebral cryopreservation; from neurophilosophy and the neurosciences; from debates about brain life and brain death; from practices of intensive care, organ transplantation, and neurological enhancement and prosthetics; from the emerging fields of neuroesthe- tics, neurotheology, neuroeconomics, neuroeducation, neuropsychoanalysis and others. This research in progress traces the diversity of neurocultures, and places them in a larger context characterized by the emergence of somatic “bioidentities” that replace psychological and internalistic notions of personhood. It does so by examining not only discourses and representations, but also concrete social practices, such as those that take shape in the politically powerful “neurodiversity” movement, or in vigorously commercialized “neuroascetic” disciplines of the self. -

Theory of Mind and Empathy As Multidimensional Constructs Neurological Foundations

Top Lang Disorders Vol. 34, No. 4, pp. 282–295 Copyright c 2014 Wolters Kluwer Health | Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Theory of Mind and Empathy as Multidimensional Constructs Neurological Foundations Jonathan Dvash and Simone G. Shamay-Tsoory Empathy describes an individual’s ability to understand and feel the other. In this article, we review recent theoretical approaches to the study of empathy. Recent evidence supports 2 possible empathy systems: an emotional system and a cognitive system. These processes are served by separate, albeit interacting, brain networks. When a cognitive empathic response is generated, the theory of mind (ToM) network (i.e., medial prefrontal cortex, superior temporal sulcus, temporal poles) and the affective ToM network (mainly involving the ventromedial prefrontal cortex) are typically involved. In contrast, the emotional empathic response is driven mainly by simulation and involves regions that mediate emotional experiences (i.e., amygdala, insula). A decreased empathic response may be due to deficits in mentalizing (cognitive ToM, affective ToM) or in simulation processing (emotional empathy), with these deficits mediated by different neural systems. It is proposed that a balanced activation of these 2 networks is required for appropriate social behavior. Key words: emotion, empathy, inferior frontal gyrus, mirror neurons, simulation, theory of mind, ventromedial prefrontal cortex NE of the core functions of individu- have provided evidence of the multidimen- O als living within a society is the attribu- sional nature of ToM. In this article, we review tion of mental states to others. This function, main approaches to the study of the neural ba- known as theory of mind (ToM) or “mental- sis of ToM and empathy (including tasks used izing” (Frith, 1999), enables an individual to to elicit them), describe the neurological un- understand or predict another person’s be- derpinnings for the multidimensional nature havior and to react accordingly. -

Visual Recognition of Words Learned with Gestures Induces Motor

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Visual recognition of words learned with gestures induces motor resonance in the forearm muscles Claudia Repetto1*, Brian Mathias2,3, Otto Weichselbaum4 & Manuela Macedonia4,5,6 According to theories of Embodied Cognition, memory for words is related to sensorimotor experiences collected during learning. At a neural level, words encoded with self-performed gestures are represented in distributed sensorimotor networks that resonate during word recognition. Here, we ask whether muscles involved in gesture execution also resonate during word recognition. Native German speakers encoded words by reading them (baseline condition) or by reading them in tandem with picture observation, gesture observation, or gesture observation and execution. Surface electromyogram (EMG) activity from both arms was recorded during the word recognition task and responses were detected using eye-tracking. The recognition of words encoded with self-performed gestures coincided with an increase in arm muscle EMG activity compared to the recognition of words learned under other conditions. This fnding suggests that sensorimotor networks resonate into the periphery and provides new evidence for a strongly embodied view of recognition memory. Traditional perspectives in cognitive science describe human behaviour as mediated by cognitive representations1. Such representations have been defned as mental structures that encode, store and process information arising from sensory-motor systems 2. According to these perspectives, information provided to perceptual systems about the environment is incomplete. As a result, the brain has the essential role of transforming this information into cognitive representations, which enable rapid and accurate behaviours. In recent years, embodied approaches have claimed that perception, action and the environment jointly contribute to cognitive processes3,4, highlighting a change in our understanding of the role of the body in cognition.