Melissa Mccann May 4, 2018 Vowel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

05-11-2019 Gotter Eve.Indd

Synopsis Prologue Mythical times. At night in the mountains, the three Norns, daughters of Erda, weave the rope of destiny. They tell how Wotan ordered the World Ash Tree, from which his spear was once cut, to be felled and its wood piled around Valhalla. The burning of the pyre will mark the end of the old order. Suddenly, the rope breaks. Their wisdom ended, the Norns descend into the earth. Dawn breaks on the Valkyries’ rock, and Siegfried and Brünnhilde emerge. Having cast protective spells on Siegfried, Brünnhilde sends him into the world to do heroic deeds. As a pledge of his love, Siegfried gives her the ring that he took from the dragon Fafner, and she offers her horse, Grane, in return. Siegfried sets off on his travels. Act I In the hall of the Gibichungs on the banks of the Rhine, Hagen advises his half- siblings, Gunther and Gutrune, to strengthen their rule through marriage. He suggests Brünnhilde as Gunther’s bride and Siegfried as Gutrune’s husband. Since only the strongest hero can pass through the fire on Brünnhilde’s rock, Hagen proposes a plan: A potion will make Siegfried forget Brünnhilde and fall in love with Gutrune. To win her, he will claim Brünnhilde for Gunther. When Siegfried’s horn is heard from the river, Hagen calls him ashore. Gutrune offers him the potion. Siegfried drinks and immediately confesses his love for her.Ð When Gunther describes the perils of winning his chosen bride, Siegfried offers to use the Tarnhelm to transform himself into Gunther. -

Musical Landmarks in New York

MUSICAL LANDMARKS IN NEW YORK By CESAR SAERCHINGER HE great war has stopped, or at least interrupted, the annual exodus of American music students and pilgrims to the shrines T of the muse. What years of agitation on the part of America- first boosters—agitation to keep our students at home and to earn recognition for our great cities as real centers of musical culture—have not succeeded in doing, this world catastrophe has brought about at a stroke, giving an extreme illustration of the proverb concerning the ill wind. Thus New York, for in- stance, has become a great musical center—one might even say the musical center of the world—for a majority of the world's greatest artists and teachers. Even a goodly proportion of its most eminent composers are gathered within its confines. Amer- ica as a whole has correspondingly advanced in rank among musical nations. Never before has native art received such serious attention. Our opera houses produce works by Americans as a matter of course; our concert artists find it popular to in- clude American compositions on their programs; our publishing houses publish new works by Americans as well as by foreigners who before the war would not have thought of choosing an Amer- ican publisher. In a word, America has taken the lead in mu- sical activity. What, then, is lacking? That we are going to retain this supremacy now that peace has come is not likely. But may we not look forward at least to taking our place beside the other great nations of the world, instead of relapsing into the status of a colony paying tribute to the mother country? Can not New York and Boston and Chicago become capitals in the empire of art instead of mere outposts? I am afraid that many of our students and musicians, for four years compelled to "make the best of it" in New York, are already looking eastward, preparing to set sail for Europe, in search of knowledge, inspiration and— atmosphere. -

André Previn Tippett's Secret History

TIPPETT’S SECRET HISTORY ANDRÉ PREVIN The fascinating story of the composer’s incendiary politics Our farewell to the musical legend 110 The world’s best-selling classical music magazine reviews by the world’s finest critics See p72 Bach at its best! Pianist Víkingur Ólafsson wins our Recording of the Year Richard Morrison Preparing students for real life Classically trained America’s railroad revolution Also in this issue Mark Simpson Karlheinz Stockhausen We meet the young composer Alina Ibragimova Brahms’s Clarinet Quintet Ailish Tynan and much more… First Transcontinental Railroad Carriage made in heaven: Sunday services on a train of the Central Pacific Railroad, 1876; (below) Leland Stanford hammers in the Golden Spike Way OutWest 150 years ago, America’s First Transcontinental Railroad was completed. Brian Wise describes how music thrived in the golden age of train travel fter the freezing morning of 10 May Key to the railroad’s construction were 1869, a crowd gathered at Utah’s immigrant labourers – mostly from Ireland and Promontory Summit to watch as a China – who worked amid avalanches, disease, A golden spike was pounded into an clashes with Native Americans and searing unfinished railroad track. Within moments, a summer heat. ‘Not that many people know how telegraph was sent from one side of the country hard it was to build, and how many perished to the other announcing the completion of while building this,’ says Zhou Tian, a Chinese- North America’s first transcontinental railroad. American composer whose new orchestral work It set off the first coast-to-coast celebration, Transcend pays tribute to these workers. -

Housekeeper J Mr

Beautiful Spring Brides. Bowery section of New York, where Among the numerous spring brides she had sung at mission meetings, to of the national capital, two of the the most critical box holder of grand of the are Miss Nora the houses in all of the world's Children for Fletcher's WEEK prettiest Pepper, I opera Cry NEWS musical The (former trade expert of the state de 'great centers. purity i partment, and Miss Sybil Scott* of her voice, employed in many Edifying Scene In New York Church. only way—by serving somebody else ! daughter of the Iowa congressman, tongues, had delighted hundreds of Three led by Bouck than themselves. And what greater Socialists, I George C. Scott. Miss Pepper is to thousands since the day, 40 years ago White, head of the Church of the So thing could you serve than a nation [ marry Dr. George W. Calver of the she first appeared in public as cial Revolution, were thrown out of such as this we love and are proud ! IT. S. Navy, and Miss Scott is engag- soprano soloist at Grace church in Calvary Baptist church, in New V'ork, of? ed to Mr. Dale Moore, a well known | Boston. which John D. Rockefeller attends, "Are you sorry for the lads Are ; newspaper man, formerly of St. Paul. Nordica and Eames—although the when White tried to speak at lust you sorry for the way they will be latter was born of American parents Kind You Have and which has been Sunday morning’s service. remembered? I hope to God none of The Always Bought, in off China—were of old New Mutual Mating of Mutes. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 11, 1891

ACADEMY OF MUSIC, PHILADELPHIA. OSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA. ARTHUR NIKISCH, Conductor. Eleventh Season, 1891-92. PROGRAMME OF THE FIRST CONCERT, Wednesday Evening, November 4, AT EIGHT O'CLOCK. Historical and Descriptive Notes prepared by G. H. WILSON. PUBLISHED BY C. A. ELLIS, Manager. I The MASON & HAMLIN PIAN Illustrates the same high standard of excellence which has always characterized th- MASON & HAMLIN ORGANS, and won for them the Highest Awards at ALI GREAT WORLD'S EXHIBITIONS since and including that of Paris, 1867 SOLD ON EASY TERMS AND RENTED. MASON & HAMLIN ORGAN AND PIANO CO BOSTON, Mason & Hamlin Hall, 154 and 155 Tremont Street. NEW YORK, 158 Fifth Avenue. CHICAGO, 149 Wabash Avenue. Or^an and Piano Catalogue sent free to any address. WM. G. FISCHER, 1221 Chestnut Street, PHILADELPHIA REPRESENTAT " Boston Academy Symphony d of Music - s^ , , SEASON OF Orchestra l89 .-92 Mr. ARTHUR N1KISCH, Conductor. First Concert, Wednesday Evening, November 4, At 8 o'clock. PROGRAMME. Seethoven --____ Overture, "Leonore," No. 3 lounod - - - - Aria from " Queen of Sheba Cschaikowsky - - Suite, Op. 55 Elegie. Valse melancholique. Scherzo. Tema con Variazioni. Jaint-Saens - - Rondo Capriccioso for Violin - !L Thomas - - Polacca from "Mignon" Wagner - - - - Prelude, "Die Meistersinger SOLOISTS: VIme. LILLIAN NORDICA. Mr. T. ADAMOWSKI, The announcement of the next Concert will be found on page 25. (3) SHORE LINE BOSTON jn NEW YORK NEW YORK U BOSTON Trains leave either city, week-days, as follows, except as noted : DAY EXPRESS at 10.00 a.m. Arrive at 4.30 p.m. BUFFET DRAWING-ROOM CARS. AFTERNOON SERVICE at 1.00 p.m. -

Wliy Have "Merves?" the Army the Objected Mr

tlOBOICA 5T E FAMOUS GRAND OPERA SINGER WHO WAS TAKEN ILL SINCLAIR cSRILLIAl IT5HINE SUDDENLY IN BOSTON. ! IS. Ai Will Make Copper AS ABOUT TO SIIIG AFFINITY PARTED Shine Like Gold Copper pots, kettles and other metal kitchen utensils can be kept brilliantly bright easily Paralysis Overcomes Great Novelist's Former Wife Tires with the use of a little of this of Life With Tramp Poet wonderful liquid metal polish. Prima Donna of Grand Requires no hard rubbing. and Uncertain Meals. Opera Stage. Sold by grocers, druggists and hardware dealers. Look " ' for the name and portrait of '' "7""' . MISSING E. VV. Bennett on each can. CONDITION IS CRITICAL HARRY KEMP IS Mora Good News Concerning the CaNkl Ruiicd on Sjwclal Train to Little Bungalow In New Jersey Now E.W. lioMon I'nim Xf York to nil Deserted and Woman Exponent Bennett Half Price Sale of Undermuslins JLove" Replenishes Co! Engagement of Soprano of "Free a Yesterday was trie first day of the wonderful Half Price Sale of Noted for Love Affair. Self at Paternal Larder. Manufacturers dainty white undermuslins and is positively the best underwear bargain will continue this San event offered this season Today, the second day, we Francisco wonder event with just as many and just as good reductions. Do not miss this sale; if you have any doubts just come in the store and see for BOSTON. Feb. IS. (Spffll) Mad- -l NEW TORK, Feb. 12. (Special.) g finest of dainty under- m Lillian Nordica. the. famous Amer-n- Mrs. Meta Sinclair, one-tim- e wife of yourself how very cheaply you can secure the soprano who rose from tha ob-K- ur Upton Sinclair, the novelist, and Harry garments. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 28

ACADEMY OF MUSIC, PHILADELPHIA Twenty-fowth Season in Philadelphia MAX FIEDLER, Conductor ftrngHmune of tht FOURTH CONCERT WITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIP- TIVE NOTES BY PHILIP HALE MONDAY EVENING, FEBRUARY 15 AT 8.15 PRECISELY COPYRIGHT, 1908, BY C. A. ELLIS PUBLISHED BY C. A. ELLIS, MANAGER Mme. CECILE CHAMINADE The 'World's Greatest Woman Composer Mme. TERESA CARRENO The World's Greatest Woman Pianist Mme. LILLIAN NORDICA The World's Greatest "Woman Singer USE THE JOHN CHURCH CO., 37 West 326 Street New York City REPRESENTED BY MUSICAL ECHO GO. 1217 Chestnut Street, Philadelphia Boston Symphony Orchestra PERSONNEL TWENTY-EIGHTH SEASON, 1908-1909 MAX FIEDLER, Conductor First Violins. Hess, Willy Roth, O. Hoffmann, J. Krafft, W. Concert-master. Kuntz, D. Fiedler, E. Theodorowicz, J. Noack, S. Mahn, F. Eichheim, H. Bak, A. Mullaly, J. Strube, G. Rissland, K. Ribarsch, A. Traupe, W.[ Second Violins. Barleben, K. Akeroyd, J. Fiedler, B. Berger, H. Fiumara, P. Currier, F. Marble, E. Eichler, J. Tischer-Zeitz, H. Kuntz, A. Goldstein, H. Goldstein, S. Kurth; R. Werner, H. Violas. FeTir, E. Heindl, H. Zahn, F. Kolster, A. Krauss, H. Scheurer, K. Hoyer, H. Kluge, M. Sauer, G. Gietzen, A. Violoncellos. Warnke, H. Nagel, R. Barth, C. Loeffler, K Warnke. J.| Keller, J. Kautzenbach, A. Nast, L. Hadley, A. Smalley, R. Basses. Keller, K. Agnesy, K. Seydel, T. Ludwig, O. Gerhardt, G. Kunze, M. Huber, E. Schurig, R. Flutes. Oboes. Clarinets. Bassoons. Maquarre, A. Longy, G. Grisez, G. Sadony, P. Maquarre, D. Lenom, C. Mimart, P. Mueller, E. Brooke, A. Sautet, A. Vannini, A. Regestein, E. -

BOOK PLATES. It Is a Hard Forest to Travel Through, Could Scarcely Refrain from Shedding Eyelid Cut Badly While Playing Ball

VOL. XXX. NO. 2. PHILLIPS, MAINE, FRIDAY, AUGUST 16, 1907. PRICE 3 CENTS JUVENILES ORGANIZE AT STRONG. to get along well here. The tracts we W ESf PHILLIPS REUNION. Frank Gray, H. R. Butterfield, J. C. I have been riding over Henry county in a have to explore contain 200 square | Wells, Octavia Blanchard, J. W. buggy and on horseback the past few days. The roads are best suited to horseback riding. Yes Franklin’s Musical Town Now Claims miles, but we are about done and are I Brackett, Henry McKenney, A. A. GATHERING OF FORMER RESIDENTS terday I looked over a four-hundred acre farm Youngest Band In State. in hopes to be able to get back in Blanchard, G. L. Kempton. once owned and occupied as a home by Patrick OF PHILLIPS AND VICINITY. Henry. If the great orator and patriot didn’t The business section of Strong was season to attend the reunion at West The address by De Berna Ross, Esq,, farm it better than the present owners are doing taken somewhat by storm one day last Phillips. was well delivered and appropriate, and There are lots of moose in this ter it, he didn’t deserve the honor of having the week when all unheralded a sound of Speeches by Residents and Visitors and received very favorable comment. county named for him. revelry and music was heard from the ritory. We often see them at the shore Letters of Regret From Those Who The reminiscences by Judge Lakin Possibly some of you may have noticed that of the ponds, but we have not had any Henry county, Va„ took the first premium on street. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 28,1908-1909, Trip

INFANTRY HALL . PROVIDENCE Twenty-eighth Season, 1908-1909 MAX FIEDLER, Conductor Programme nf % FIRST CONCERT WITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIP- TIVE NOTES BY PHILIP HALE TUESDAY EVENING, NOVEMBER 24 AT 8. J 5 PRECISELY COPYRIGHT, 1908, BY C. A. ELLIS PUBLISHED BY- C. A. ELLIS, MANAGER Mme. CECILE CHAMINADE The World's Greatest Woman Composer Mme. TERESA CARRENO The World's Greatest Woman Pianist Mme. LILLIAN NORDICA The World's Greatest Woman Singer USE Piano. THE JOHN CHURCH CO., 37 West $2d Street New York City REPRESENTED BY THE JOHN CHURCH CO., 37 West 32d Street, New York City Boston Symphony Orchestra PERSONNEL TWENTY-EIGHTH SEASON, 1908-1909 MAX FIEDLER, Conductor First Violins. Hess, Willy Roth, O. Hoffmann, J. Krafft, W. Concert-master. Kuntz, D. Fiedler, E. Theodorowicz, J, Noack, S. Mahn, F. Eichheim, H. Bak, A. Mullaly, J. Strube, G. Rissland, K. Ribarsch, A. Traupe, W. Second Violins. Barleben, K. Akeroyd, J. Fiedler, B. Berger, H. Fiumara, P. Currier, F. Werner, H. Eichler, J. Tischer-Zeitz, H. Kuntz, A. Marble, E. Goldstein, S. Kurth, R. Goldstein, H. Violas. Fenr, E. Heindl, H. Zahn, F. Kolster, A. Krauss, H. Scheurer, K. Hoyer, H. Kluge, M. Sauer, G. Gietzen, A. Violoncellos. Warnke, H. Nagel, R. Barth, C. Loeffler, E. Warnke, J. Keller, J. Kautzenbach, A. Nast, L. Hadley, A. Smalley, R. Basses. Keller, K. Agnesy, K. Seydel, T. Ludwig, O. Gerhardt, G. Kunze, M. Huber, E. Schurig, R. Flutes. Oboes. Clarinets. Bassoons. Maquarre, A. Longy, G. Grisez, G. Sadony, P. Maquarre, D. Lenom, C. Mimart, P. Mueller, E. Brooke, A. Sautet, A. -

Tristan Und Isolde

Richard Wagner Tristan und Isolde CONDUCTOR Opera in three acts James Levine Libretto by the composer PRODUCTION Dieter Dorn Saturday, March 22, 2008, 12:30–5:30pm SET AND COSTUME DESIGNER Jürgen Rose LIGHTING DESIGNER Max Keller The production of Tristan und Isolde was made possible by a generous gift from Mr. and Mrs. Henry R. Kravis. Additional funding for this production was generously provided by Mr. and Mrs. Sid R. Bass, Raffaella and Alberto Cribiore, The Eleanor Naylor Dana Charitable Trust, Gilbert S. Kahn and John J. Noffo Kahn, Mr. and Mrs. Paul M. Montrone, Mr. and Mrs. Ezra K. Zilkha, and one anonymous donor. The revival of this production is made possible by a generous gift from The Gilbert S. Kahn and John J. Noffo GENERAL MANAGER Kahn Foundation. Peter Gelb MUSIC DIRECTOR James Levine 2007-08 Season The 447th Metropolitan Opera performance of Richard Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde Conductor James Levine IN ORDER OF VOCAL APPEARANCE A Sailor’s Voice King Marke Matthew Plenk Matti Salminen Isolde A Shepherd Deborah Voigt Mark Schowalter Brangäne M A Steersman Deborah Voigt’s Michelle DeYoung James Courtney performance is underwritten by Kurwenal Eike Wilm Schulte the Annenberg English horn solo Principal Artist Tristan Pedro R. Díaz Fund. Robert Dean Smith DEBUT This afternoon’s performance is Melot being broadcast Stephen Gaertner live on Metropolitan Opera Radio, on Sirius Satellite Radio channel 85. Saturday, March 22, 2008, 12:30–5:30pm This afternoon’s performance is being transmitted live in high definition to movie theaters worldwide. The Met: Live in HD is generously supported by the Neubauer Family Foundation. -

Die Grossen Sänger Unseres Jahrhunderts

Jürgen Kesting DIE GROSSEN SÄNGER UNSERES JAHRHUNDERTS ECON Verlag Düsseldorf • Wien • New York • Moskau V Inhalt Zur Neuausgabe XQI Vorwort XV EINLEITUNG Eine Stimme zur rechten Zeit Vorspiel auf dem Theater 3 Dialog mit der Ewigkeit 5 Sänger und Schallplatte 6 Von verlorener und wiedergefundener Zeit 9 Von Treue und Untreue 10 Von den Perspektiven der Zeit 12 I. KAPITEL Der ferne Klang oder: Die alte Schule Belcanto 17 Nachtigall: Adelina Patti 18 • Grandeur: Lilli Lehmann 25 • The Ideal Voice of Song: Nellie Melba 32 • »Ich habe gelernt, nie zu schreien«: Ernestine Schumann-Heink 42 • Die einzigartige Stimme der Welt: Francesco Tamagno 46 Tenor-Virtuose: Fernando de Lucia 50 • La Gloria d'Italia: Mattia Battistini 57 • Der vollkommene Sänger: Pol Plancon 62 II. KAPITEL Zeitenwende oder: Die Wandlungen des Singens Vollendung und Ende des Belcanto 69 Wer hat DICH geschickt? Gott? Enrico Caruso 71 Im Schatten Carusos 83 Esultate: Giovanni Zenatello 84 • Tenore di grazia: Alessandro Bonci 86 • Femme fatale: Emma Calve 90 • Eines von drei Wundern: Rosa Ponselle 95 • Der singende Löwe: Titta Ruffo 103 Goldenes Zeitalter der Baritone 108 Sänger-Schauspieler: Antonio Scotti 109 • Energie und Stimmpracht: Pasquale Amato in • Flexibilität und Phrasierungskunst: Giuseppe de Luca 114 Dämon der Darstellung: 119 Der Mephisto von Kasan: Fedor Schaljapin 119 VI INHALT III. KAPITEL Italien: Die Geburt des Verismo Arturo Toscanini und die Folgen 131 Italienische Diven 137 Memento an den Belcanto: Giannina Russ 138 Zwei große Primadonnen 139 Mischung -

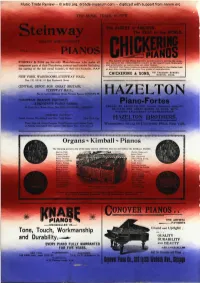

Teinway the BEST in the D

Music Trade Review -- © mbsi.org, arcade-museum.com -- digitized with support from namm.org RADE REVIEW Yhe OLDEST in AMERICA. teinway The BEST in the D. GRAND AND UPRIGHT PIANOS The history of the Piano industry in this country proves the supe- STEINWAY & SONS are the only Manufacturers who make all rior value of the CHICKERING PIANO to the dealer, both financially component parts of their Pianofortes, exterior and interior (including and artistically, as leader over all other makes. TO-DAY the Piano presents greater possibilities for the dealer than the casting of the full metal frames), in their own factories, at any time during1 our seventy-flve years of manufacture. 791 TREMONT STREET, CHICKERING & SONS, BOSTON, MASS. NEW YORK WAREROOMS, STEINWAY HALL, Nos. J07, 109 & \U East Fourteenth Street. CENTRAL DEPOT FOR GREAT BRITAIN, STEINWAY HALL, No. J5 Lower Seymour Street, Portman Square, LONDON, HAZELTON EUROPEAN BRANCH FACTORY, STEINWAVS PIANO FABRIK, Piano-Fortes St. Pauli, Neue Rosen Strasse, Nos. 20-24, HAMBURG, GERMANY. CANNOT BE EXCELLED FOR TOUCH, SINGING QUALITY, DELICATE AND GREAT POWER OF TONE, WITH HIGHEST EXCELLENCE OF WORKMANSHIP. FINISHING FACTORY: Fourth Avenue, Fifty-Second and Fifty-Third Streets. New York City. HAZELTON BROTHERS, .^•••••••••••••••••••••1 !••••••••••••••••••••••••• Piano Case and Action Factories, Metal Foundries and Lumber Yards, Warerooms: 66 and 68 University Place, New York at Astoria, Long Island City, opposite 120th Street. New York City. ^ yzsagsras^ggyz^ac^^ Organs~ Kimball ~ Pianos The following are but a few of the many musical celebrities who use and endorse the KIMBALL PIAN05: Adelina Patti Walter Damrosch Emma Calve Anton Seidl Lillian Nordica Geo.