Prisoner Health Background Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Unofficial Prisoner Cell Block H Companion Free

FREE BEHIND THE BARS: THE UNOFFICIAL PRISONER CELL BLOCK H COMPANION PDF Scott Anderson,Barry Campbell,Rob Cope,Barry Humphries | 312 pages | 12 Aug 2013 | Tomahawk Press | 9780956683441 | English | Sheffield, United Kingdom Prisoner (TV series) - Wikipedia Please sign in to write a review. If you have changed your email address then contact us and we will update your details. Would you like to proceed to the App store to download the Waterstones App? We have recently updated our Privacy Policy. The site uses cookies to offer you a Behind the Bars: The Unofficial Prisoner Cell Block H Companion experience. By continuing to browse the site you accept our Cookie Policy, you can change your settings at any time. Not available This Behind the Bars: The Unofficial Prisoner Cell Block H Companion is currently unavailable. This item has been added to your basket View basket Checkout. Added to basket. May Week Was In June. Clive James. Lynda Bellingham. Last of the Summer Wine. Andrew Vine. Not That Kind of Girl. Lena Dunham. Match of the Day Quiz Book. My Animals and Other Family. Clare Balding. Confessions of a Conjuror. Derren Brown. Hiroshima mon amour. Marguerite Duras. Just One More Thing. Peter Falk. George Cole. Tony Wilson. Life on Air. Sir David Attenborough. John Motson. Collected Screenplays. Hanif Kureishi. Holly Hagan. Falling Towards England. Your review has been submitted successfully. Not registered? Remember me? Forgotten password Please enter your email address below and we'll send you a link to reset your password. Not you? Reset password. Download Now Dismiss. Simply reserve online and pay at the counter when you collect. -

Judgment Day the Judgments and Sentences of 18 Horrific Australian Crimes

Judgment Day The judgments and sentences of 18 horrific Australian crimes EDITED BY BeN COLLINS Prelude by The Hon. Marilyn Warren AC MANUSCRIPT FOR MEDIA USE ONLY NO CONTENT MUST BE REPRODUCED WITHOUT PERMISSION PLEASE CONTACT KARLA BUNNEY ON (03) 9627 2600 OR [email protected] Judgment Day The judgments and sentences of 18 horrific Australian crimes MEDIA GROUP, 2011 COPYRIGHTEDITED BY OF Be THEN COLLINS SLATTERY Prelude by The Hon. Marilyn Warren AC Contents PRELUDE Taking judgments to the world by The Hon. Marilyn Warren AC ............................9 INTRODUCTION Introducing the judgments by Ben Collins ...............................................................15 R v MARTIN BRYANT .......................................17 R v JOHN JUSTIN BUNTING Sentenced: 22 November, 1996 AND ROBERT JOE WAGNER ................222 The Port Arthur Massacre Sentenced: 29 October, 2003 The Bodies in the Barrels REGINA v FERNANDO ....................................28 Sentenced: 21 August, 1997 THE QUEEN and BRADLEY Killer Cousins JOHN MURDOCH ..............................................243 Sentenced: 15 December, 2005 R v ROBERTSON ...................................................52 Murder in the Outback Sentenced: 29 November, 2000 Deadly Obsession R v WILLIAMS .....................................................255 Sentenced: 7 May, 2007 R v VALERA ................................................................74 Fatboy’s Whims Sentenced: 21 December, 2000MEDIA GROUP, 2011 The Wolf of Wollongong THE QUEEN v McNEILL .............................291 -

IN the UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the NORTHERN DISTRICT of WEST VIRGINIA JONATHAN LEE RICHES, Plaintiff, V. Civil Action N

Case 1:08-cv-00027-FPS Document 5 Filed 01/23/08 Page 1 of 22 PageID #: <pageID> IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF WEST VIRGINIA JONATHAN LEE RICHES, Plaintiff, v. Civil Action No. 1:08CV2 WAYNE DIERKS, Defendant. JONATHAN LEE RICHES, Plaintiff, v. Civil Action No. 1:08CV3 ANTHONY CLINKENBEARD, Defendant. JONATHAN LEE RICHES, Plaintiff, v. Civil Action No. 1:08CV4 JOANN BOLLIGER, Defendant. JONATHAN LEE RICHES, Plaintiff, v. Civil Action No. 1:08CV5 KIMBERLY KLINGLER and JOHN KLINGLER, Defendants. JONATHAN LEE RICHES, Plaintiff, v. Civil Action No. 1:08CV6 STEFANIE COSTLEY DOYLE, Defendant. JONATHAN LEE RICHES, Plaintiff, v. Civil Action No. 1:08CV7 BETHANY A. BRANON, Defendant. JONATHAN LEE RICHES, Plaintiff, v. Civil Action No. 1:08CV8 STACEY PAVESI DEBRE, Defendant. JONATHAN LEE RICHES, Plaintiff, v. Civil Action No. 1:08CV9 WINONA RYDER, d/b/a Saks Fifth Ave., Defendant. Case 1:08-cv-00027-FPS Document 5 Filed 01/23/08 Page 2 of 22 PageID #: <pageID> JONATHAN LEE RICHES, Plaintiff, v. Civil Action No. 1:08CV10 DANIEL TANI and ROSE TANI, Defendants. JONATHAN LEE RICHES, Plaintiff, v. Civil Action No. 1:08CV11 RATKO MLADIC, Defendant. JONATHAN LEE RICHES, Plaintiff, v. Civil Action No. 1:08CV12 MAKSIM CHMERKOVSKIY, Defendant. JONATHAN LEE RICHES, Plaintiff, v. Civil Action No. 1:08CV13 STEPHEN M. HEDLUND, and OLAF WOLFF, Defendants. JONATHAN LEE RICHES, Plaintiff, v. Civil Action No. 1:08CV20 CARLOTTA GALL, d/b/a New York Times Reporter, Defendant. JONATHAN LEE RICHES, Plaintiff, v. Civil Action No. 1:08CV21 MARGARET TALEV, d/b/a McClatchy News Service Reporter, Defendant. -

(Not) a Number : Decoding the Prisoner Pdf Free

I AM (NOT) A NUMBER : DECODING THE PRISONER PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Alex Cox | 208 pages | 01 May 2018 | Oldcastle Books Ltd | 9780857301758 | English | United Kingdom I Am (not) A Number : Decoding The Prisoner PDF Book Not all prisoners are paid for their work, and wages paid for prison labor generally are very low—only cents per hour. In fact, the incarceration rates of white and Hispanic women in particular are growing more rapidly than those of other demographic groups Guerino et al. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics report Probation and Parole in the United States, , Appendix Table 3, 98, adults exited probation to incarceration under their current sentence; Appendix Table 7 shows 69, adults were returned to incarceration from parole with a revocation. See Wright The percentage of federal prisons offering vocational training also has been increasing, from 62 percent in to 98 percent in The social contact permitted with chaplains, counselors, psychologists,. We discuss each of these limitations in turn. Rehabilitation—the goal of placing people in prison not only as punishment but also with the intent that they eventually would leave better prepared to live a law-abiding life—had served as an overarching rationale for incarceration for nearly a. This represents an increase of approximately 17 percent over the numbers held in and, based on the current Bureau of Prisons prisoner population, indicates that approximately 15, federal inmates are confined in restricted housing. If someone convicted of robbery is arrested years later for a liquor law violation, it makes no sense to view this very different, much less serious, offense the same way we would another arrest for robbery. -

Introduction

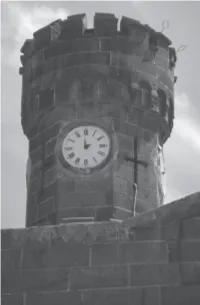

INTRODUCTION In early 1970, I took a position as an education officer at Pentridge Prison in the Melbourne suburb of Coburg. Assigned to the high- security B Division, where the chapel doubled as the only classroom on weekdays, I became tutor, confidant and counsellor to some of Australia’s best-known criminals. I’d previously taught adult students at Keon Park Technical School for several years, but nothing could prepare me for the inhospitable surrounds I faced in B Division. No bright and cheerful classroom or happy young faces here – just barren grey walls and barred windows, and the sad faces of prisoners whose contact with me was often their only link to a dimly remembered world outside. The eerie silence of the empty cell block was only punctuated by the occasional approach of footsteps and the clanging of the grille gate below. Although it’s some forty years since I taught in Pentridge, the place and its people have never left me. In recent times, my adult children encouraged me to write an account of my experiences there, and this book is the result. Its primary focus is on the 1970s, which were years of rebellion in Pentridge, as in jails across the Western world. These were also the years when I worked at Pentridge, feeling tensions rise across the prison. The first chapter maps the prison’s evolution from its origins in 1850 until 1970, and the prison authorities’ struggle to adapt to changing philosophies of incarceration over that time. The forbidding exterior of Pentridge was a sign of what lay inside; once it was constructed, this nineteenth-century prison was literally set in stone, a soulless place of incarceration that was nevertheless the only home that many of its inmates had known. -

(Her Regular Understudy), Kerry Armstrong Seemed Set for International Stardom

“She’s a really good actress. She’s also a little bit mad”: (right) Kerry Armstrong in her garden in Melbourne’s eastern hills. Photography Marina Oliphant CARRY ON KERRY With fans like trouper Sid James and future Oscar-winner Helen Hunt (her regular understudy), Kerry Armstrong seemed set for international stardom. So why didn’t the talented actor take Hollywood by storm? Dani Valent fi nds out. t’s 1975, it’s dawn, and kerry armstrong is 16 years old. she’s belly-down on her twin-fin surfboard, paddling out to meet the waves at Point Leo, an hour south-east of Melbourne. She can’t see much because she’s very short-sighted and her big, thick glasses are I lying on a towel on the sand. She can see colours – the dipping and looming green of the water, the blurred white soles of the boy paddling in front – but that’s it.When the water flattens, the teenage surfers stop, turn in the water and wait. Soon Armstrong feels the sea swell, hears a gathering rumble, and knows a set is approaching. She can’t see the waves, so she waits for the boys to yell – “Go, Kerry! Go go go!” – then paddles hard. A wave picks her up and she stands, a goofy-foot in a bikini, and swoops down the hard wall of water, riding blind to the shore.“I can’t believe I surfed without being able to see,” she says, startled at the memory. “I was fearless. What trust I had in the world.” At the time, Armstrong was a spirited schoolgirl actress. -

Prisoner Reentry in Perspective

CRIME POLICY REPORT CRIME POLICY Vol. 3, September 2001 Vol. Prisoner Reentry in Perspective James P. Lynch William J. Sabol research for safer communities URBAN INSTITUTE Justice Policy Center Prisoner Reentry in Perspective James P. Lynch William J. Sabol Crime Policy Report Vol. 3, September 2001 copyright © 2001 About the Authors The Urban Institute 2100 M Street, NW Washington, DC 20037 James P. Lynch is a Professor in the William J. Sabol is a Senior Research www.urban.org Department of Justice, Law, and Society Associate at the Center on Urban (202) 833-7200 at the American University. His Poverty and Social Change at Case interests include theories of victimiza- Western Reserve University, where he is The views expressed are those of the au- tion, crime statistics, international the Center's Associate Director for thors and should not be attributed to the comparisons of crime and crime Community Analysis. His research Urban Institute, its trustees, or its funders. control policies and the role of incar- focuses on crime and communities, Designed by David Williams ceration in social control. He is co- including the impacts of justice author (with Albert Biderman) of practices on public safety and commu- Understanding Crime Incidence Statistics: nity organization. He is currently Why the UCR diverges from the NCS. His working on studies of ex-offender Previous Crime Policy Reports: more recent publications include a employment, of minority confinement chapter on cross-national comparisons in juvenile detentions, and of the Did Getting Tough on Crime Pay? of crime and punishment in Crime relationship between changes in James P. -

Prisoners' Rights to Physical and Mental Health Care: a Modern Expansion of the Eight Amendment's Cruel and Unusual Punishment Clause Stuart Klein [email protected]

Fordham Urban Law Journal Volume 7 | Number 1 Article 1 1979 Prisoners' Rights to Physical and Mental Health Care: A Modern Expansion of the Eight Amendment's Cruel and Unusual Punishment Clause Stuart Klein [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ulj Part of the Criminal Law Commons Recommended Citation Stuart Klein, Prisoners' Rights to Physical and Mental Health Care: A Modern Expansion of the Eight Amendment's Cruel and Unusual Punishment Clause , 7 Fordham Urb. L.J. 1 (1979). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ulj/vol7/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Urban Law Journal by an authorized editor of FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Prisoners' Rights to Physical and Mental Health Care: A Modern Expansion of the Eight Amendment's Cruel and Unusual Punishment Clause Cover Page Footnote A note of appreciation is extended to Professors Vincent Nathan, Frank Merritt, and Judy Beckner Sloan This article is available in Fordham Urban Law Journal: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ulj/vol7/iss1/1 PRISONERS' RIGHTS TO PHYSICAL AND MENTAL HEALTH CARE: A MODERN EXPANSION OF THE EIGHTH AMENDMENT'S CRUEL AND UNUSUAL PUNISHMENT CLAUSE Stuart B. Klein* I. Introduction In recent years, the primary constitutional amendment used as a means to alleviate poor prison conditions has been the eighth amendment's prohibition against the infliction of cruel and unusual punishment.' The eighth amendment to the United States Consti- tution' is interpreted to prohibit certain actions by the government and to require other affirmative actions.' This prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment is often utilized to insure that ade- quate health care, including psychiatric care, is provided for in- mates. -

Australia's Criminal Justice Costs: an International Comparison

April 2017 AUSTRALIA’S CRIMINAL JUSTICE COSTS AN INTERNATIONAL COMPARISON Andrew Bushnell, Research Fellow This page intentionally left blank AUSTRALIA’S CRIMINAL JUSTICE COSTS: AN INTERNATIONAL COMPARISON Andrew Bushnell, Research Fellow This report was updated in December 2017 to take advantage of new figures from 2015 About the author Andrew Bushnell is a Research Fellow at the Institute of Public Affairs, working on the Criminal Justice Project. He previously worked in policy at the Department of Education in Melbourne and in strategic communications at the Department of Defence in Canberra. Andrew holds a Bachelor of Arts (Hons.) and a Bachelor of Laws from Monash University, and a Master of Arts from Linköping University in Sweden. Australia’s Criminal Justice Costs: An International Comparison This page intentionally left blank Contents 1. Australian prisons are expensive 4 2. Australian prison expenditure is growing rapidly 6 3. Australia’s prison population is also growing rapidly 8 4. Australia also has a high level of police spending 10 5. Australians are heavily-policed 12 6. Australians do not feel safe 14 7. Australians may experience more crime than citizens of comparable countries 16 8. Australia has a class of persistent criminals 18 Australia’s Criminal Justice Costs: An International Comparison 1 2 Institute of Public Affairs Research www.ipa.org.au Overview Incarceration in Australia is growing rapidly. The 2016 adult incarceration rate was 208 per 100,000 adults, up 28 percent from 2006. There are now more than 36,000 prisoners, up 39 percent from a decade ago. The Institute of Public Affairs Criminal Justice Project has investigated the causes of this increase and policy ideas for rationalising the use of prisons in its reports, The Use of Prisons in Australia: Reform directions and Criminal justice reform: Lessons from the United States. -

Convicts, Coolies and Colonialism: Reorienting the Prisoner-Of-War Narrative

Convicts, Coolies and Colonialism: reorienting the prisoner-of-war narrative FRANCES DE GROEN University of Western Sydney espite its remarkable scope, popularity and durability, the Australian prisoner�f D war narrative from the Pacific War, in both documentaryand imaginative forms, has generated little critical attention.1 Scholarly interest in it (as in prisoners-of-war more generally) is a relatively recent phenomenon, identifying it as a dissonant sub genre of Australian war writing's dominant 'big-noting' Anzac tradition . Drawing on Carnochan 's concept of 'the literature of confinement', this paper aims to enrich the dialogue about the Pacific War captivity narrative by reading it as 'prison' literature rather than as a branch of 'war' writing. It will also consider the significance of allusions to the Robinson Crusoe myth (a core trope of confinement literature), in the Australian convict and prisoner-of-war traditions. Due to constraints of space, the approach adopted is somewhat schematic and impressionistic and represents ·work in progress' rather than final thoughts. Robin Gerster ( 1987) established the prevailing terms of reference of the Pacific War captivity narrative. For Gerster, because the prisoner-of-war narrative allegedly fo cuses on the captive's 'shame' at being denied his rightful place on the battlefield, writers of prisoner-of-war narrative face 'an acute problem of "public relations"': how to make the non-combatant role attractive.2 Their strategies for dealing with this problem include 'special pleading of passive suffering' (i.e. exploiting the horror and hardship of captivity) and seeking 'vicarious vengeance through mercilessly attacking [the] old enemy in print'. -

Policy Directive 69 Management of Prisoner's Money

Policy Directive 69 Management of Prisoner's Money Relevant instruments: ACCO Notices: 7/2013 and 8/2013 Financial Management Act 2006 Operational Instruction 1 Policy Directives 3 and 36 Prisons Regulations 1982 rr 43-50 and 73 Standard Guidelines for Corrections in Australia 2004 ss 1.13-1.15, 2.21-2.23, 1.17, 3.21, 4.3 and 5.18 Table of Contents Purpose .............................................................................................................................1 Background........................................................................................................................1 1. Handling of Money......................................................................................................2 2. Prisoners Private Cash ...............................................................................................2 3. Access to Private Cash...............................................................................................3 4. Prisoners' Gratuity Earnings .......................................................................................3 5. Access to Gratuities....................................................................................................3 6. Prisoner's Telephone Account ....................................................................................4 7. Restitution...................................................................................................................4 8. Quality Control ............................................................................................................5 -

Punishment in Prison the World of Prison Discipline

Punishment in Prison The world of prison discipline Key points • Prisons operate disciplinary hearings called • Since 2010 the number of adjudications adjudications where allegations of rule where extra days could be imposed has breaking are tried increased by 47 per cent. The running cost • The majority of adjudications concern of these hearings is significant, at around disobedience, disrespect, or property £400,000 – £500,000 per year offences, all of which increase as prisons lose • Adjudications are not sufficiently flexible to control under pressure of overcrowding and deal sensitively with the needs of vulnerable staff cuts children, mentally ill and self-harming people, • A prisoner found guilty at an adjudication who may face trial and sentence without can face a variety of punishments from loss any legal representation. The process and of canteen to solitary confinement and extra punishments often make their problems worse days of imprisonment • Two prisoners breaking the same rule can get • Almost 160,000 extra days, or 438 years, of different punishments depending on whether imprisonment were imposed in 2014 as a they are on remand or sentenced, and what result of adjudications category of sentence they have received. • The number of additional days imposed on • Two children breaking the same rule can get children has doubled since 2012, even though different punishments depending on what type the number of children in prison has halved of institution they are detained in. out-of-control prisons it has become a routinely used The world of prison discipline Life in prison is framed by the Prison Rules 1999 behaviour management technique.