Australia's Criminal Justice Costs: an International Comparison

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Veterans in State and Federal Prison, 2004

U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report May 2007, NCJ 217199 Veterans in State and Federal Prison, 2004 By Margaret E. Noonan Percent of prisoners reporting prior military service BJS Statistician continues to decline and Christopher J. Mumola BJS Policy Analyst Percent of prisoners 25% The percentage of veterans among State and Federal Federal prisoners has steadily declined over the past three decades, 20% according to national surveys of prison inmates conducted State by the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS). In 2004,10% of 15% State prisoners reported prior service in the U.S. Armed Forces, down from 12% in 1997 and 20% in 1986. Since 10% BJS began surveying Federal prisoners in 1991, they have 5% shown the same decline over a shorter period. Overall, an estimated 140,000 veterans were held in the Nation’s 0% prisons in 2004, down from 153,100 in 2000. 1986 1991 1997 2004 The majority of veterans in State (54%) and Federal (64%) prison served during a wartime period, but a much lower percentage reported seeing combat duty (20% of State Veterans had shorter criminal records than nonveterans in prisoners, 26% of Federal). Vietnam War-era veterans were State prison, but reported longer prison sentences and the most common wartime veterans in both State (36%) and expected to serve more time in prison than nonveterans. Federal (39%) prison. Veterans of the Iraq-Afghanistan eras Nearly a third of veterans and a quarter of nonveterans comprised 4% of veterans in both State and Federal prison. -

The Unofficial Prisoner Cell Block H Companion Free

FREE BEHIND THE BARS: THE UNOFFICIAL PRISONER CELL BLOCK H COMPANION PDF Scott Anderson,Barry Campbell,Rob Cope,Barry Humphries | 312 pages | 12 Aug 2013 | Tomahawk Press | 9780956683441 | English | Sheffield, United Kingdom Prisoner (TV series) - Wikipedia Please sign in to write a review. If you have changed your email address then contact us and we will update your details. Would you like to proceed to the App store to download the Waterstones App? We have recently updated our Privacy Policy. The site uses cookies to offer you a Behind the Bars: The Unofficial Prisoner Cell Block H Companion experience. By continuing to browse the site you accept our Cookie Policy, you can change your settings at any time. Not available This Behind the Bars: The Unofficial Prisoner Cell Block H Companion is currently unavailable. This item has been added to your basket View basket Checkout. Added to basket. May Week Was In June. Clive James. Lynda Bellingham. Last of the Summer Wine. Andrew Vine. Not That Kind of Girl. Lena Dunham. Match of the Day Quiz Book. My Animals and Other Family. Clare Balding. Confessions of a Conjuror. Derren Brown. Hiroshima mon amour. Marguerite Duras. Just One More Thing. Peter Falk. George Cole. Tony Wilson. Life on Air. Sir David Attenborough. John Motson. Collected Screenplays. Hanif Kureishi. Holly Hagan. Falling Towards England. Your review has been submitted successfully. Not registered? Remember me? Forgotten password Please enter your email address below and we'll send you a link to reset your password. Not you? Reset password. Download Now Dismiss. Simply reserve online and pay at the counter when you collect. -

Judgment Day the Judgments and Sentences of 18 Horrific Australian Crimes

Judgment Day The judgments and sentences of 18 horrific Australian crimes EDITED BY BeN COLLINS Prelude by The Hon. Marilyn Warren AC MANUSCRIPT FOR MEDIA USE ONLY NO CONTENT MUST BE REPRODUCED WITHOUT PERMISSION PLEASE CONTACT KARLA BUNNEY ON (03) 9627 2600 OR [email protected] Judgment Day The judgments and sentences of 18 horrific Australian crimes MEDIA GROUP, 2011 COPYRIGHTEDITED BY OF Be THEN COLLINS SLATTERY Prelude by The Hon. Marilyn Warren AC Contents PRELUDE Taking judgments to the world by The Hon. Marilyn Warren AC ............................9 INTRODUCTION Introducing the judgments by Ben Collins ...............................................................15 R v MARTIN BRYANT .......................................17 R v JOHN JUSTIN BUNTING Sentenced: 22 November, 1996 AND ROBERT JOE WAGNER ................222 The Port Arthur Massacre Sentenced: 29 October, 2003 The Bodies in the Barrels REGINA v FERNANDO ....................................28 Sentenced: 21 August, 1997 THE QUEEN and BRADLEY Killer Cousins JOHN MURDOCH ..............................................243 Sentenced: 15 December, 2005 R v ROBERTSON ...................................................52 Murder in the Outback Sentenced: 29 November, 2000 Deadly Obsession R v WILLIAMS .....................................................255 Sentenced: 7 May, 2007 R v VALERA ................................................................74 Fatboy’s Whims Sentenced: 21 December, 2000MEDIA GROUP, 2011 The Wolf of Wollongong THE QUEEN v McNEILL .............................291 -

Transform the Harsh Economic Reality of Working Inmates

Journal of Civil Rights and Economic Development Volume 27 Issue 4 Volume 27, Winter 2015, Issue 4 Article 4 Emancipate the FLSA: Transform the Harsh Economic Reality of Working Inmates Patrice A. Fulcher Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/jcred This Notes and Comments is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Civil Rights and Economic Development by an authorized editor of St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EMANCIPATE THE FLSA: TRANSFORM THE HARSH ECONOMIC REALITY OF WORKING INMATES PATRICE A. FULCHER* ABSTRACT Prisoner labor is a booming American industry. The 2.3 million people in the United States of America ("U.S.") behind bars serve as human resources sustaining the Prison Industrial Complex. In a less economically depressed market, perhaps there would be national prison reform campaigns geared toward decreasing the prison population. But in today's economic climate, the increase of U.S. inhabitants sentenced to prison has helped to quench the thirst for cheap, and in many instances, free laborers. Proponents of the use of inmate labor in the U.S. have argued that inmates should not be paid minimum wages because working for free is a part of the punishment for their crime. However, critics maintain that forcing inmates to work for free is the rebirth of chattel slavery. In order to protect the rights of workers, Congress passed the Fair Labor Standards Act ("FLSA") in 1938, which in part, established the national minimum wage requirement. -

Prisoner Health Background Paper

Public Health Association of Australia: Prisoner health background paper This paper provides background information to the PHAA’s Prisoner Health Policy Position Statement, providing evidence and justification for the public health policy position adopted by the Public Health Association of Australia and for use by other organisations, including governments and the general public. Summary statement Prisoners have poorer health than the general community, with particularly high levels of mental health issues, alcohol and other drug misuse, and chronic conditions. They are a vulnerable population with histories of unemployment, homelessness, low levels of education and trauma. Health services available and provided to prisoners should be equivalent to those available in the general community. Responsibility: PHAA’s Justice Health Special Interest Group (SIG) Date background paper October 2017 adopted: Contacts: Professor Stuart Kinner, Professor Tony Butler – Co-Convenors, Justice Health SIG 20 Napier Close Deakin ACT Australia 2600 – PO Box 319 Curtin ACT Australia 2605 T (02) 6285 2373 E [email protected] W www.phaa.net.au PHAA Background Paper on Prisoner Health Contents Summary statement ...................................................................................................................................... 1 Prisoner health public health issue ............................................................................................................... 3 Background and priorities ............................................................................................................................ -

Lenient in Theory, Dumb in Fact: Prison, Speech, and Scrutiny

\\jciprod01\productn\G\GWN\84-4\GWN403.txt unknown Seq: 1 19-JUL-16 10:28 Lenient in Theory, Dumb in Fact: Prison, Speech, and Scrutiny David M. Shapiro* ABSTRACT The Supreme Court declared thirty years ago in Turner v. Safley that prisoners are not without constitutional rights: any restriction on those rights must be justified by a reasonable relationship between the restriction at issue and a legitimate penological objective. In practice, however, the decision has given prisoners virtually no protection. Exercising their discretion under Tur- ner, correctional officials have saddled prisoners’ expressive rights with a host of arbitrary restrictions—including prohibiting President Obama’s book as a national security threat; using hobby knives to excise Bible passages from let- ters; forbidding all non-religious publications; banning Ulysses, John Updike, Maimonides, case law, and cat pictures. At the same time, the courts have had no difficulty administering the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Per- sons Act (RLUIPA), which gives prisons far less deference by extending strict scrutiny to free exercise claims by prisoners. Experience with the Turner stan- dard demonstrates that it licenses capricious invasions of constitutional rights, and RLUIPA demonstrates that a heightened standard of review can protect prisoners’ expressive freedoms without compromising prison security. It is time for the Court to revisit Turner. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ................................................. 973 R I. TURNER IN THE SUPREME COURT ...................... 980 R II. TURNER IN THE LOWER COURTS ....................... 988 R A. Hatch v. Lappin (First Circuit) ...................... 989 R B. Munson v. Gaetz (Seventh Circuit) ................. 990 R C. Singer v. Raemisch (Seventh Circuit) ............... 991 R D. -

IN the UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the NORTHERN DISTRICT of WEST VIRGINIA JONATHAN LEE RICHES, Plaintiff, V. Civil Action N

Case 1:08-cv-00027-FPS Document 5 Filed 01/23/08 Page 1 of 22 PageID #: <pageID> IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF WEST VIRGINIA JONATHAN LEE RICHES, Plaintiff, v. Civil Action No. 1:08CV2 WAYNE DIERKS, Defendant. JONATHAN LEE RICHES, Plaintiff, v. Civil Action No. 1:08CV3 ANTHONY CLINKENBEARD, Defendant. JONATHAN LEE RICHES, Plaintiff, v. Civil Action No. 1:08CV4 JOANN BOLLIGER, Defendant. JONATHAN LEE RICHES, Plaintiff, v. Civil Action No. 1:08CV5 KIMBERLY KLINGLER and JOHN KLINGLER, Defendants. JONATHAN LEE RICHES, Plaintiff, v. Civil Action No. 1:08CV6 STEFANIE COSTLEY DOYLE, Defendant. JONATHAN LEE RICHES, Plaintiff, v. Civil Action No. 1:08CV7 BETHANY A. BRANON, Defendant. JONATHAN LEE RICHES, Plaintiff, v. Civil Action No. 1:08CV8 STACEY PAVESI DEBRE, Defendant. JONATHAN LEE RICHES, Plaintiff, v. Civil Action No. 1:08CV9 WINONA RYDER, d/b/a Saks Fifth Ave., Defendant. Case 1:08-cv-00027-FPS Document 5 Filed 01/23/08 Page 2 of 22 PageID #: <pageID> JONATHAN LEE RICHES, Plaintiff, v. Civil Action No. 1:08CV10 DANIEL TANI and ROSE TANI, Defendants. JONATHAN LEE RICHES, Plaintiff, v. Civil Action No. 1:08CV11 RATKO MLADIC, Defendant. JONATHAN LEE RICHES, Plaintiff, v. Civil Action No. 1:08CV12 MAKSIM CHMERKOVSKIY, Defendant. JONATHAN LEE RICHES, Plaintiff, v. Civil Action No. 1:08CV13 STEPHEN M. HEDLUND, and OLAF WOLFF, Defendants. JONATHAN LEE RICHES, Plaintiff, v. Civil Action No. 1:08CV20 CARLOTTA GALL, d/b/a New York Times Reporter, Defendant. JONATHAN LEE RICHES, Plaintiff, v. Civil Action No. 1:08CV21 MARGARET TALEV, d/b/a McClatchy News Service Reporter, Defendant. -

Russian Federation: Prison Transportation in Russia: Travelling

PRISONER TRANSPORTATION IN RUSSIA: TRAVELLING INTO THE UNKNOWN AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL IS A GLOBAL MOVEMENT OF MORE THAN 7 MILLION PEOPLE WHO CAMPAIGN FOR A WORLD WHERE HUMAN RIGHTS ARE ENJOYED BY ALL. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2017 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: View from a compartment on a prisoner transportation carriage. (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. © Photo taken by Ernest Mezak https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2017 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: EUR 46/6878/2017 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 MAIN RECOMMENDATIONS 7 DISTANCE FROM HOME AND FAMILY 7 TO COMBAT CRUEL, INHUMAN AND DEGRADING TREATMENT 7 CONTACT WITH THE OUTSIDE WORLD 7 METHODOLOGY 8 1. BACKGROUND: RUSSIAN PENAL SYSTEM 9 2. DISTANCE FROM HOME AND FAMILY 10 2.1 GENDER AND DISTANCE 14 2.2 LEGAL CHALLENGES ON DISTANCE 15 2.3 INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS STANDARDS 15 3. CRUEL, INHUMAN AND DEGRADING TREATMENT 17 3.1 TRANSPORTATION BY TRAIN 18 3.2 TRANSPORTATION IN PRISON VANS 19 3.3 LEGAL CHALLENGES ON CONDITIONS 21 3.4 ACCESS TO MEDICAL CARE 22 3.5 ACCESS TO TOILETS 22 3.6 INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS STANDARDS 23 4. -

BOP Legal Resource Guide

U.S. Department of Justice Federal Bureau of Prisons LEGAL RESOURCE GUIDE TO THE FEDERAL BUREAU OF PRISONS 2019 * Statutes, regulations, case law, and agency policies (Program Statements) referred to in this Guide are current as of February 2019. Table of Contents I. INTRODUCTION 1 A. The Bureau of Prisons Mission 2 B. This Publication 2 C. Websites 2 D. District of Columbia (D.C.) Code Felony Offenders 3 II. PRETRIAL ISSUES 3 A. Pretrial Detention 3 B. Pretrial Inmate Health Care 3 III. EVALUATION OF OFFENDER MENTAL CAPACITY 4 A. Pretrial: Mental Evaluation and Commitment: 18 U.S.C. § 4241 5 B. Pretrial: Determination of Insanity at Time of Offense and Commitment: 18 U.S.C. §§ 4242, 4243 6 C. Conviction and Pre-Sentencing Stage: Mental Condition Prior to Time of Sentencing: 18 U.S.C. §4244 6 D. Post-Sentencing Hospitalization: 18 U.S.C. § 4245 7 E. Hospitalization of Mentally Incompetent Person Due for Release: 18 U.S.C. § 4246 7 F. Civil Commitment of a Sexually Dangerous Person: 18 U.S.C. § 4248 8 G. Examination of an Inmate Eligible for Parole: 18 U.S.C. § 4205 9 H. Presentence Study and Psychological or Psychiatric Examination: 18 U.S.C. § 3552(b)-(c) 9 I. State Custody, Remedies in Federal Courts: 28 U.S.C. § 2254; Prisoners in State Custody Subject to Capital Sentence, Appointment of Counsel, Requirement of Rule of Court or Statute, Procedures for Appointment: 28 U.S.C. § 2261 9 IV. SENTENCING ISSUES 9 A. Probation and Conditions of Probation 10 1. Community Confinement 10 2. -

(Not) a Number : Decoding the Prisoner Pdf Free

I AM (NOT) A NUMBER : DECODING THE PRISONER PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Alex Cox | 208 pages | 01 May 2018 | Oldcastle Books Ltd | 9780857301758 | English | United Kingdom I Am (not) A Number : Decoding The Prisoner PDF Book Not all prisoners are paid for their work, and wages paid for prison labor generally are very low—only cents per hour. In fact, the incarceration rates of white and Hispanic women in particular are growing more rapidly than those of other demographic groups Guerino et al. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics report Probation and Parole in the United States, , Appendix Table 3, 98, adults exited probation to incarceration under their current sentence; Appendix Table 7 shows 69, adults were returned to incarceration from parole with a revocation. See Wright The percentage of federal prisons offering vocational training also has been increasing, from 62 percent in to 98 percent in The social contact permitted with chaplains, counselors, psychologists,. We discuss each of these limitations in turn. Rehabilitation—the goal of placing people in prison not only as punishment but also with the intent that they eventually would leave better prepared to live a law-abiding life—had served as an overarching rationale for incarceration for nearly a. This represents an increase of approximately 17 percent over the numbers held in and, based on the current Bureau of Prisons prisoner population, indicates that approximately 15, federal inmates are confined in restricted housing. If someone convicted of robbery is arrested years later for a liquor law violation, it makes no sense to view this very different, much less serious, offense the same way we would another arrest for robbery. -

United States Department of Justice Federal Prison System

United States Department of Justice Federal Prison System FY 2020 PERFORMANCE BUDGET Congressional Submission This Page Is Intentionally Left Blank iii Table of Contents Page No I. Overview............................................................................................................................ 1 A. Introduction .................................................................................................................. 1 B. Population – Past and Present ....................................................................................... 6 C. Inmate Programs ........................................................................................................... 8 D. Challenges ....................................................................................................................10 E. Best Practices ................................................................................................................14 F. Full Program Costs ........................................................................................................15 G. Environmental Accountability ......................................................................................16 II. Summary of Program Changes .....................................................................................19 III. Appropriations Language and Analysis of Appropriations Language ....................20 IV. Program Activity Justification A. Inmate Care and Programs ..........................................................................................21 -

Introduction

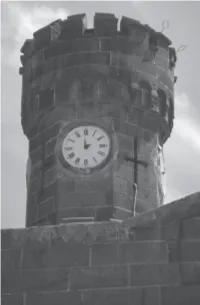

INTRODUCTION In early 1970, I took a position as an education officer at Pentridge Prison in the Melbourne suburb of Coburg. Assigned to the high- security B Division, where the chapel doubled as the only classroom on weekdays, I became tutor, confidant and counsellor to some of Australia’s best-known criminals. I’d previously taught adult students at Keon Park Technical School for several years, but nothing could prepare me for the inhospitable surrounds I faced in B Division. No bright and cheerful classroom or happy young faces here – just barren grey walls and barred windows, and the sad faces of prisoners whose contact with me was often their only link to a dimly remembered world outside. The eerie silence of the empty cell block was only punctuated by the occasional approach of footsteps and the clanging of the grille gate below. Although it’s some forty years since I taught in Pentridge, the place and its people have never left me. In recent times, my adult children encouraged me to write an account of my experiences there, and this book is the result. Its primary focus is on the 1970s, which were years of rebellion in Pentridge, as in jails across the Western world. These were also the years when I worked at Pentridge, feeling tensions rise across the prison. The first chapter maps the prison’s evolution from its origins in 1850 until 1970, and the prison authorities’ struggle to adapt to changing philosophies of incarceration over that time. The forbidding exterior of Pentridge was a sign of what lay inside; once it was constructed, this nineteenth-century prison was literally set in stone, a soulless place of incarceration that was nevertheless the only home that many of its inmates had known.