Teachers'resources

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Unofficial Prisoner Cell Block H Companion Free

FREE BEHIND THE BARS: THE UNOFFICIAL PRISONER CELL BLOCK H COMPANION PDF Scott Anderson,Barry Campbell,Rob Cope,Barry Humphries | 312 pages | 12 Aug 2013 | Tomahawk Press | 9780956683441 | English | Sheffield, United Kingdom Prisoner (TV series) - Wikipedia Please sign in to write a review. If you have changed your email address then contact us and we will update your details. Would you like to proceed to the App store to download the Waterstones App? We have recently updated our Privacy Policy. The site uses cookies to offer you a Behind the Bars: The Unofficial Prisoner Cell Block H Companion experience. By continuing to browse the site you accept our Cookie Policy, you can change your settings at any time. Not available This Behind the Bars: The Unofficial Prisoner Cell Block H Companion is currently unavailable. This item has been added to your basket View basket Checkout. Added to basket. May Week Was In June. Clive James. Lynda Bellingham. Last of the Summer Wine. Andrew Vine. Not That Kind of Girl. Lena Dunham. Match of the Day Quiz Book. My Animals and Other Family. Clare Balding. Confessions of a Conjuror. Derren Brown. Hiroshima mon amour. Marguerite Duras. Just One More Thing. Peter Falk. George Cole. Tony Wilson. Life on Air. Sir David Attenborough. John Motson. Collected Screenplays. Hanif Kureishi. Holly Hagan. Falling Towards England. Your review has been submitted successfully. Not registered? Remember me? Forgotten password Please enter your email address below and we'll send you a link to reset your password. Not you? Reset password. Download Now Dismiss. Simply reserve online and pay at the counter when you collect. -

Judgment Day the Judgments and Sentences of 18 Horrific Australian Crimes

Judgment Day The judgments and sentences of 18 horrific Australian crimes EDITED BY BeN COLLINS Prelude by The Hon. Marilyn Warren AC MANUSCRIPT FOR MEDIA USE ONLY NO CONTENT MUST BE REPRODUCED WITHOUT PERMISSION PLEASE CONTACT KARLA BUNNEY ON (03) 9627 2600 OR [email protected] Judgment Day The judgments and sentences of 18 horrific Australian crimes MEDIA GROUP, 2011 COPYRIGHTEDITED BY OF Be THEN COLLINS SLATTERY Prelude by The Hon. Marilyn Warren AC Contents PRELUDE Taking judgments to the world by The Hon. Marilyn Warren AC ............................9 INTRODUCTION Introducing the judgments by Ben Collins ...............................................................15 R v MARTIN BRYANT .......................................17 R v JOHN JUSTIN BUNTING Sentenced: 22 November, 1996 AND ROBERT JOE WAGNER ................222 The Port Arthur Massacre Sentenced: 29 October, 2003 The Bodies in the Barrels REGINA v FERNANDO ....................................28 Sentenced: 21 August, 1997 THE QUEEN and BRADLEY Killer Cousins JOHN MURDOCH ..............................................243 Sentenced: 15 December, 2005 R v ROBERTSON ...................................................52 Murder in the Outback Sentenced: 29 November, 2000 Deadly Obsession R v WILLIAMS .....................................................255 Sentenced: 7 May, 2007 R v VALERA ................................................................74 Fatboy’s Whims Sentenced: 21 December, 2000MEDIA GROUP, 2011 The Wolf of Wollongong THE QUEEN v McNEILL .............................291 -

Prisoner Health Background Paper

Public Health Association of Australia: Prisoner health background paper This paper provides background information to the PHAA’s Prisoner Health Policy Position Statement, providing evidence and justification for the public health policy position adopted by the Public Health Association of Australia and for use by other organisations, including governments and the general public. Summary statement Prisoners have poorer health than the general community, with particularly high levels of mental health issues, alcohol and other drug misuse, and chronic conditions. They are a vulnerable population with histories of unemployment, homelessness, low levels of education and trauma. Health services available and provided to prisoners should be equivalent to those available in the general community. Responsibility: PHAA’s Justice Health Special Interest Group (SIG) Date background paper October 2017 adopted: Contacts: Professor Stuart Kinner, Professor Tony Butler – Co-Convenors, Justice Health SIG 20 Napier Close Deakin ACT Australia 2600 – PO Box 319 Curtin ACT Australia 2605 T (02) 6285 2373 E [email protected] W www.phaa.net.au PHAA Background Paper on Prisoner Health Contents Summary statement ...................................................................................................................................... 1 Prisoner health public health issue ............................................................................................................... 3 Background and priorities ............................................................................................................................ -

IN the UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the NORTHERN DISTRICT of WEST VIRGINIA JONATHAN LEE RICHES, Plaintiff, V. Civil Action N

Case 1:08-cv-00027-FPS Document 5 Filed 01/23/08 Page 1 of 22 PageID #: <pageID> IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF WEST VIRGINIA JONATHAN LEE RICHES, Plaintiff, v. Civil Action No. 1:08CV2 WAYNE DIERKS, Defendant. JONATHAN LEE RICHES, Plaintiff, v. Civil Action No. 1:08CV3 ANTHONY CLINKENBEARD, Defendant. JONATHAN LEE RICHES, Plaintiff, v. Civil Action No. 1:08CV4 JOANN BOLLIGER, Defendant. JONATHAN LEE RICHES, Plaintiff, v. Civil Action No. 1:08CV5 KIMBERLY KLINGLER and JOHN KLINGLER, Defendants. JONATHAN LEE RICHES, Plaintiff, v. Civil Action No. 1:08CV6 STEFANIE COSTLEY DOYLE, Defendant. JONATHAN LEE RICHES, Plaintiff, v. Civil Action No. 1:08CV7 BETHANY A. BRANON, Defendant. JONATHAN LEE RICHES, Plaintiff, v. Civil Action No. 1:08CV8 STACEY PAVESI DEBRE, Defendant. JONATHAN LEE RICHES, Plaintiff, v. Civil Action No. 1:08CV9 WINONA RYDER, d/b/a Saks Fifth Ave., Defendant. Case 1:08-cv-00027-FPS Document 5 Filed 01/23/08 Page 2 of 22 PageID #: <pageID> JONATHAN LEE RICHES, Plaintiff, v. Civil Action No. 1:08CV10 DANIEL TANI and ROSE TANI, Defendants. JONATHAN LEE RICHES, Plaintiff, v. Civil Action No. 1:08CV11 RATKO MLADIC, Defendant. JONATHAN LEE RICHES, Plaintiff, v. Civil Action No. 1:08CV12 MAKSIM CHMERKOVSKIY, Defendant. JONATHAN LEE RICHES, Plaintiff, v. Civil Action No. 1:08CV13 STEPHEN M. HEDLUND, and OLAF WOLFF, Defendants. JONATHAN LEE RICHES, Plaintiff, v. Civil Action No. 1:08CV20 CARLOTTA GALL, d/b/a New York Times Reporter, Defendant. JONATHAN LEE RICHES, Plaintiff, v. Civil Action No. 1:08CV21 MARGARET TALEV, d/b/a McClatchy News Service Reporter, Defendant. -

(Not) a Number : Decoding the Prisoner Pdf Free

I AM (NOT) A NUMBER : DECODING THE PRISONER PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Alex Cox | 208 pages | 01 May 2018 | Oldcastle Books Ltd | 9780857301758 | English | United Kingdom I Am (not) A Number : Decoding The Prisoner PDF Book Not all prisoners are paid for their work, and wages paid for prison labor generally are very low—only cents per hour. In fact, the incarceration rates of white and Hispanic women in particular are growing more rapidly than those of other demographic groups Guerino et al. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics report Probation and Parole in the United States, , Appendix Table 3, 98, adults exited probation to incarceration under their current sentence; Appendix Table 7 shows 69, adults were returned to incarceration from parole with a revocation. See Wright The percentage of federal prisons offering vocational training also has been increasing, from 62 percent in to 98 percent in The social contact permitted with chaplains, counselors, psychologists,. We discuss each of these limitations in turn. Rehabilitation—the goal of placing people in prison not only as punishment but also with the intent that they eventually would leave better prepared to live a law-abiding life—had served as an overarching rationale for incarceration for nearly a. This represents an increase of approximately 17 percent over the numbers held in and, based on the current Bureau of Prisons prisoner population, indicates that approximately 15, federal inmates are confined in restricted housing. If someone convicted of robbery is arrested years later for a liquor law violation, it makes no sense to view this very different, much less serious, offense the same way we would another arrest for robbery. -

Introduction

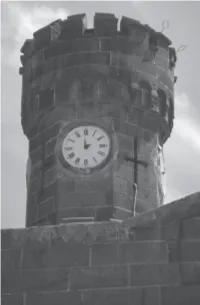

INTRODUCTION In early 1970, I took a position as an education officer at Pentridge Prison in the Melbourne suburb of Coburg. Assigned to the high- security B Division, where the chapel doubled as the only classroom on weekdays, I became tutor, confidant and counsellor to some of Australia’s best-known criminals. I’d previously taught adult students at Keon Park Technical School for several years, but nothing could prepare me for the inhospitable surrounds I faced in B Division. No bright and cheerful classroom or happy young faces here – just barren grey walls and barred windows, and the sad faces of prisoners whose contact with me was often their only link to a dimly remembered world outside. The eerie silence of the empty cell block was only punctuated by the occasional approach of footsteps and the clanging of the grille gate below. Although it’s some forty years since I taught in Pentridge, the place and its people have never left me. In recent times, my adult children encouraged me to write an account of my experiences there, and this book is the result. Its primary focus is on the 1970s, which were years of rebellion in Pentridge, as in jails across the Western world. These were also the years when I worked at Pentridge, feeling tensions rise across the prison. The first chapter maps the prison’s evolution from its origins in 1850 until 1970, and the prison authorities’ struggle to adapt to changing philosophies of incarceration over that time. The forbidding exterior of Pentridge was a sign of what lay inside; once it was constructed, this nineteenth-century prison was literally set in stone, a soulless place of incarceration that was nevertheless the only home that many of its inmates had known. -

Prisoner Reentry in Perspective

CRIME POLICY REPORT CRIME POLICY Vol. 3, September 2001 Vol. Prisoner Reentry in Perspective James P. Lynch William J. Sabol research for safer communities URBAN INSTITUTE Justice Policy Center Prisoner Reentry in Perspective James P. Lynch William J. Sabol Crime Policy Report Vol. 3, September 2001 copyright © 2001 About the Authors The Urban Institute 2100 M Street, NW Washington, DC 20037 James P. Lynch is a Professor in the William J. Sabol is a Senior Research www.urban.org Department of Justice, Law, and Society Associate at the Center on Urban (202) 833-7200 at the American University. His Poverty and Social Change at Case interests include theories of victimiza- Western Reserve University, where he is The views expressed are those of the au- tion, crime statistics, international the Center's Associate Director for thors and should not be attributed to the comparisons of crime and crime Community Analysis. His research Urban Institute, its trustees, or its funders. control policies and the role of incar- focuses on crime and communities, Designed by David Williams ceration in social control. He is co- including the impacts of justice author (with Albert Biderman) of practices on public safety and commu- Understanding Crime Incidence Statistics: nity organization. He is currently Why the UCR diverges from the NCS. His working on studies of ex-offender Previous Crime Policy Reports: more recent publications include a employment, of minority confinement chapter on cross-national comparisons in juvenile detentions, and of the Did Getting Tough on Crime Pay? of crime and punishment in Crime relationship between changes in James P. -

Australia's Criminal Justice Costs: an International Comparison

April 2017 AUSTRALIA’S CRIMINAL JUSTICE COSTS AN INTERNATIONAL COMPARISON Andrew Bushnell, Research Fellow This page intentionally left blank AUSTRALIA’S CRIMINAL JUSTICE COSTS: AN INTERNATIONAL COMPARISON Andrew Bushnell, Research Fellow This report was updated in December 2017 to take advantage of new figures from 2015 About the author Andrew Bushnell is a Research Fellow at the Institute of Public Affairs, working on the Criminal Justice Project. He previously worked in policy at the Department of Education in Melbourne and in strategic communications at the Department of Defence in Canberra. Andrew holds a Bachelor of Arts (Hons.) and a Bachelor of Laws from Monash University, and a Master of Arts from Linköping University in Sweden. Australia’s Criminal Justice Costs: An International Comparison This page intentionally left blank Contents 1. Australian prisons are expensive 4 2. Australian prison expenditure is growing rapidly 6 3. Australia’s prison population is also growing rapidly 8 4. Australia also has a high level of police spending 10 5. Australians are heavily-policed 12 6. Australians do not feel safe 14 7. Australians may experience more crime than citizens of comparable countries 16 8. Australia has a class of persistent criminals 18 Australia’s Criminal Justice Costs: An International Comparison 1 2 Institute of Public Affairs Research www.ipa.org.au Overview Incarceration in Australia is growing rapidly. The 2016 adult incarceration rate was 208 per 100,000 adults, up 28 percent from 2006. There are now more than 36,000 prisoners, up 39 percent from a decade ago. The Institute of Public Affairs Criminal Justice Project has investigated the causes of this increase and policy ideas for rationalising the use of prisons in its reports, The Use of Prisons in Australia: Reform directions and Criminal justice reform: Lessons from the United States. -

Policy Directive 69 Management of Prisoner's Money

Policy Directive 69 Management of Prisoner's Money Relevant instruments: ACCO Notices: 7/2013 and 8/2013 Financial Management Act 2006 Operational Instruction 1 Policy Directives 3 and 36 Prisons Regulations 1982 rr 43-50 and 73 Standard Guidelines for Corrections in Australia 2004 ss 1.13-1.15, 2.21-2.23, 1.17, 3.21, 4.3 and 5.18 Table of Contents Purpose .............................................................................................................................1 Background........................................................................................................................1 1. Handling of Money......................................................................................................2 2. Prisoners Private Cash ...............................................................................................2 3. Access to Private Cash...............................................................................................3 4. Prisoners' Gratuity Earnings .......................................................................................3 5. Access to Gratuities....................................................................................................3 6. Prisoner's Telephone Account ....................................................................................4 7. Restitution...................................................................................................................4 8. Quality Control ............................................................................................................5 -

Punishment in Prison the World of Prison Discipline

Punishment in Prison The world of prison discipline Key points • Prisons operate disciplinary hearings called • Since 2010 the number of adjudications adjudications where allegations of rule where extra days could be imposed has breaking are tried increased by 47 per cent. The running cost • The majority of adjudications concern of these hearings is significant, at around disobedience, disrespect, or property £400,000 – £500,000 per year offences, all of which increase as prisons lose • Adjudications are not sufficiently flexible to control under pressure of overcrowding and deal sensitively with the needs of vulnerable staff cuts children, mentally ill and self-harming people, • A prisoner found guilty at an adjudication who may face trial and sentence without can face a variety of punishments from loss any legal representation. The process and of canteen to solitary confinement and extra punishments often make their problems worse days of imprisonment • Two prisoners breaking the same rule can get • Almost 160,000 extra days, or 438 years, of different punishments depending on whether imprisonment were imposed in 2014 as a they are on remand or sentenced, and what result of adjudications category of sentence they have received. • The number of additional days imposed on • Two children breaking the same rule can get children has doubled since 2012, even though different punishments depending on what type the number of children in prison has halved of institution they are detained in. out-of-control prisons it has become a routinely used The world of prison discipline Life in prison is framed by the Prison Rules 1999 behaviour management technique. -

Cultural Genocide: Sierra Leone Elected a New 71

CITIZENS VOICES VOLUME 10 JUNE 2018 CONTENTS 4. Editorial 23. Harmful Genital Surgeries 43. Rise of the Invisible: 65. Standing in Solidarity Dr Zoi Aliozi on Intersex Infants Human Rights Violations with Kashmir Jason Bach and the Emergence of LGBT Zulekha Iqbal 8. Overview Movements in India Athanasia Zagorianou 26. Beijing 2020 and Tibet Sudha Menon 67. According to me… Matthew Taylor Sarfaraz Ahmed Sangi 11. Gun Control 49. Are North Koreans Really Dervla Potter 29. Protection of human rights Persecuted? An Analysis on 69. Salam Aldeen: Hero during armed conflicts: The role Songbun of Refugees accused of 14. Crafting Resistance: of INGOS and NGOS Yoonjeong You people trafficking Preserving and Exhibiting Kwadwo Konadu Dervla Potter the Legacy of Human Rights 53. Tears of agony as Resistance through the Art of 34. Cultural Genocide: Sierra Leone elected a new 71. Interview – SIFH+ Chilean Political Prisoners A legitimate Crime government: An eye for an eye Athanasia Zagorianou Paul Dudman Gerard Maguire makes a blind nation Amidu Kolakoh 75. On the Shelf- Reading 19. To Address Corruption is 38 Sexual violence against Human Rights to Address Human Rights women in armed conflicts in 57. Gender equality in the Dervla Potter Derek Catsam North Africa and the Middle collective labor conventions East vs the International Arlete Maracaipe Cardoso Freire 79. Human Rights Cinema 22. Portrayal of Sexual Criminal Court action: CRW Team Aggression in Hindi Cinema Brief analysis 61. The right to development Umang Gupta & Madhu Kumari Manoela Galende Costa in Latin America: Claiming a 82. Cartoons legitimate right of people Aseem Trivedi Waldo Rodrigo Aramayo Soliz Razan was a first responder at the "Great Rest in peace Razan al-Najar. -

Remote Control: the Role of TV in Prison

Remote Control: the role of TV in prison Victoria Knight considers the different roles TV viewing plays in prisons, and points to the dangers of using TV access as another means of control. he experience of being a 'prisoner' is well documented, TV can mark time at a slower pace than other activities such as as are experiences of watching TV, and there is a smaJJ interacting with other people or writing a letter. For some, Tamount of research on prisoners' experiences as TV television is a remedy to quash and divert periods of boredom, audiences (Vandebosch 2001, Knight 2001 and Jewkes 2002). whereas others find prolonged experiences of watching TV futile While there have been some negative comments in the press and an additional 'pain' of their experience of incarceration. about prisoners' access to TV, research indicates a complex situation. The introduction of in-cell TV to prisons from 1995 Remote control onwards has, for example, contributed to the control and It is well documented that the prison regime has always sought regulation of behaviour, thus benefiting the regime and to control and restrict forms of communication and that enforced becoming a significant instrument of punishment. isolation and loneliness is a major experience of imprisonment (Forsythe, 2004). Today the IEP system formalises, facilitates Prisoners watching TV and orchestrates access to communications, including TV, and Watching TV is the most popular activity in Britain today. Our is an underlying mechanism for controlling prisoners. The role everyday lives, especially in our domestic spheres, have become that TV (particularly in-cell TV) has in the administration of 'saturated' (O'Sullivan et al 1998) by mass communications, the regime is that it: especially TV, which on average we spend 29 hours each week • Serves as a reward for desirable behaviour and conduct, but watching (BARB, 2005).