“A Just Cause for War”: New York’S Dred Scott Decision by William H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table of Contents

T a b l e C o n T e n T s I s s u e 9 s u mm e r 2 0 1 3 o f pg 4 pg 18 pg 26 pg 43 Featured articles Pg 4 abraham lincoln and Freedom of the Press A Reappraisal by Harold Holzer Pg 18 interbranch tangling Separating Our Constitutional Powers by Judith s. Kaye Pg 26 rutgers v. Waddington Alexander Hamilton and the Birth Pangs of Judicial Review by David a. Weinstein Pg 43 People v. sanger and the Birth of Family Planning clinics in america by Maria T. Vullo dePartments Pg 2 From the executive director Pg 58 the david a. Garfinkel essay contest Pg 59 a look Back...and Forward Pg 66 society Officers and trustees Pg 66 society membership Pg 70 Become a member Back inside cover Hon. theodore t. Jones, Jr. In Memoriam Judicial Notice l 1 From the executive director udicial Notice is moving forward! We have a newly expanded board of editors Dearwho volunteer Members their time to solicit and review submissions, work with authors, and develop topics of legal history to explore. The board of editors is composed J of Henry M. Greenberg, Editor-in-Chief, John D. Gordan, III, albert M. rosenblatt, and David a. Weinstein. We are also fortunate to have David l. Goodwin, Assistant Editor, who edits the articles and footnotes with great care and knowledge. our own Michael W. benowitz, my able assistant, coordinates the layout and, most importantly, searches far and wide to find interesting and often little-known images that greatly compliment and enhance the articles. -

Extensions of Remarks E356 HON. ALAN S. LOWENTHAL HON

E356 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks March 21, 2017 NATIONAL ROSIE THE RIVETER IN HONOR OF ALABAMA STATE I honor all of the work Kitty accomplished in DAY: A TRIBUTE TO THE LONG UNIVERSITY’S WAR GARDENS our community and the trail she blazed for the BEACH ROSIE THE RIVETER women inspired by her achievements. PARK HON. MARTHA ROBY f OF ALABAMA PERSONAL EXPLANATION HON. ALAN S. LOWENTHAL IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Tuesday, March 21, 2017 HON. LUIS V. GUTIE´RREZ OF CALIFORNIA Mrs. ROBY. Mr. Speaker, I rise today to OF ILLINOIS IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES honor Alabama State University upon its 100 IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES year anniversary of planting war gardens to Tuesday, March 21, 2017 Tuesday, March 21, 2017 aid the United States efforts in World War I. Mr. GUTIE´ RREZ. Mr. Speaker, I was un- Mr. LOWENTHAL. Mr. Speaker, I am a One hundred years ago, students, staff, and avoidably absent in the House chamber for roll proud co-sponsor of House Resolution 162, faculty of the then State Normal School at call votes 173, 174, 175 on Monday, March which will designate March 21, 2017, as Na- Montgomery, subsequently Alabama State 20, 2017. Had I been present, I would have tional Rosie the Riveter Day. This honor has University, assisted and advised residents voted ‘‘Yea’’ on roll call votes 173, 174, and special significance for the City of Long near campus and in the City of Montgomery, 175. Beach, California which I represent. Alabama on how to plant war gardens. Thanks f to these efforts, it was reported that in March Long Beach is one of two locations in the 1918 over 1,400 black homes in Montgomery SPECIAL TRIBUTE IN HONOR OF nation that has a park dedicated to recog- had war gardens. -

Impersonal Names Index Listing for the INSCOM Investigative Records Repository, 2010

Description of document: US Army Intelligence and Security Command (INSCOM) Impersonal Names Index Listing for the INSCOM Investigative Records Repository, 2010 Requested date: 07-August-2010 Released date: 15-August-2010 Posted date: 23-August-2010 Title of document Impersonal Names Index Listing Source of document: Commander U.S. Army Intelligence & Security Command Freedom of Information/Privacy Office ATTN: IAMG-C-FOI 4552 Pike Road Fort George G. Meade, MD 20755-5995 Fax: (301) 677-2956 Note: The IMPERSONAL NAMES index represents INSCOM investigative files that are not titled with the name of a person. Each item in the IMPERSONAL NAMES index represents a file in the INSCOM Investigative Records Repository. You can ask for a copy of the file by contacting INSCOM. The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. -

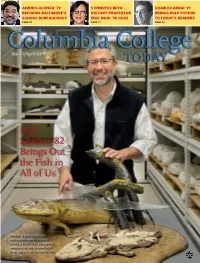

Neil Shubin '82 Brings out the Fish in All of Us

ANDRES ALONSO ’79 5 MINUTES WITH … CHARLES ARDAI ’91 REFORMS BALTIMORE’S HISTORY PROFESSOR BRINGS PULP FICTION SCHOOL BUREAUCRACY MAE NGAI ’98 GSAS TO TODAY’S READERS PAGE 22 PAGE 11 PAGE 24 Columbia College March/April 2011 TODAY Neil Shubin ’82 Brings Out the Fish in All of Us Shubin, a paleontologist and evolutionary biologist, co-led a team that discovered evidence of the pivotal shift from aquatic to terrestrial life. ust another J membership perk. Meet. Dine. Entertain. Join the Columbia Club and access state-of-the-art meeting rooms for your conferences and events. For more information or to apply, visit www.columbiaclub.org or call (212) 719-0380. The Columbia University Club of New York in residence at 15 West 43 St. New York, N Y 10036 Columbia’s SocialIntellectualCulturalRecreationalProfessional Resource in Midtown. Columbia College Today Contents 22 12 24 7 56 18 COVER STORY ALUMNI NEWS DEPARTMENTS G O FISH 27 O BITUARIES 2 LETTERS TO THE 12 Paleontologist and evolutionary biologist Neil Shubin 27 Joseph D. Coffee Jr. ’41 EDITOR ’82 brings out the fish in all of us. 28 Garland E. Wood ’65 3 ITHIN THE AMILY By Nathalie Alonso ’08 W F 30 B OOKSHEL F 4 AROUND THE QUADS FEATURES Featured: Adam Gidwitz ’04 4 turns classic folklore on its Northwest Corner Building Opens COLUMBIA FORUM ear with his new children’s 18 book, A Tale Dark & Grimm. 5 Rose, Jones Join In an excerpt from his book How Soccer Explains the College Senior Staff World: An Unlikely Theory of Globalization, Franklin 32 LASS OTES 6 Creed To Deliver Foer ’96 explains how one soccer club’s destiny was C N A LUMNI PRO F ILES Class Day Address shaped by European anti-Semitism. -

Business Valuation Reports

FEBRUARY 2010 VOL. 82 | NO. 2 JournalNEW YORK STATE BAR ASSOCIATION Business Valuation Reports The Importance of Proactive Also in this Issue Lawyering A Primer on the New York By Peter E. Bronstein False Claims Act and David A. Typermass Employment Waivers and Releases “Moot Points” 866-FUNDS- NOW Pre-Settlement Finance BESTSELLERS FROM THE NYSBA BOOKSTORE February 2010 Debt Collection and the Enforcement The Plaintiff’s Personal Injury Action in NEW! of Money Judgments, Second Edition New York State (2008) This treatise answers the tough questions faced by Attorney Escrow Accounts – Rules, Monetary awards determined in court cases involve an the plaintiff’s personal injury attorney every day – Regulations and Related Topics, 3rd array of procedures that attorneys must know. The new liens, special needs trusts, structures, Medicare and Edition second edition, under the editorship of Paul A. Peters, Medicaid, conflicts of interest, workers’ compensa- This new edition provides useful guidance on Esq., not only updates case and statutory law but also tion, no-fault, bankruptcy, representing a party in escrow funds and agreements, IOLA accounts and addresses new issues within this field, providing in-depth infancy, incompetency and wrongful death. the Lawyers’ Fund for Client Protection. The greatly topical analyses. PN: 4181 / Member $175 / List $225 / 1,734 pages expanded appendix features statutes, regulations PN: 40308 / Member $125 / List $170 / 548 pages and forms. PN: 40269 / Member $45 / List $55 / 330 pages Practitioner’s Handbook for Foundation Evidence, Questions and Appeals to the Court of Appeals, Best Practices in Legal Management Courtroom Protocols, Second Edition Third Edition The most complete and exhaustive treatment of (2009) This new edition updates topics on taking and the business aspects of running a law firm available anywhere. -

Judicial Opinion Writing: Gerald Lebovits

JUDICIAL OPINION WRITING For State Tax Judges October 12, 2018 Chicago, Illinois GERALD LEBOVITS Acting Justice, NYS Supreme Court Adjunct Professor of Law, Columbia Law School Adjunct Professor of Law, Fordham University School of Law Adjunct Professor of Law, New York University School of Law Judicial Opinion Writing For State Tax Judges October 12, 2018 By: Gerald Lebovits Table of Contents Gerald Lebovits, Alifya V. Curtin & Lisa Solomon, Ethical Judicial Opinion Writing, 21 Geo. J. Legal Ethics 237 (2008).................................................................................... A Gerald Lebovits, The Legal Writer, Ethical Judicial Writing—Part I, 78 N.Y. St. B.J. 64 (Nov./Dec. 2006) ................................................................................. B Gerald Lebovits, The Legal Writer, Ethical Judicial Writing—Part II, 79 N.Y. St. B.J. 64 (Jan. 2007) ........................................................................................... C Gerald Lebovits, The Legal Writer, Ethical Judicial Writing—Part III, 79 N.Y. St. B.J. 64 (Feb. 2007)........................................................................................... D Gerald Lebovits, The Legal Writer, Legal-Writing Ethics—Part I, 77 N.Y. St. B.J. 64 (Oct. 2005) ........................................................................................... E Gerald Lebovits, The Legal Writer, Legal-Writing Ethics—Part II, 77 N.Y. St. B.J. 64 (Nov./Dec. 2005) ................................................................................. F Gerald -

Judge Bentley Kassal

Judge Bentley Kassal Counsel, New York Litigation Judge Bentley Kassal joined Skadden, Arps in 1998 after a long and distinguished career in the judiciary and the New York legislature. He advises on litigation matters, especially regarding the appellate process. Judge Kassal was elected to the New York state legislature in 1957 and served through 1962. While a legislator, he authored the New York Arts Council Law, the first law of its kind in the United States, and testified before the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Labor and Education in support of the U.S. Council on The Arts Bill. From 1970 to 1993, he served on New York courts, including the New York City Civil Court, the New York Supreme Court, the Appellate Division of the Supreme Court and the Court of Appeals for the April/May 1985 term. Judge Kassal serves on several professional committees in New York, including the Office of New York Court Administration’s Advisory Committee on Judicial Ethics, the T: 212.735.4145 Appellate Division, Supreme Court, First Department’s Committee on Character and Fitness, F: 917.777.4145 and the Mayor’s Committee on City Marshals. [email protected] Judge Kassal is active in charitable and pro bono efforts, particularly as a photographer for Save the Children and other charities for at least 35 years. He lectures frequently, including Education talks with his photos about his World War II overseas experiences, and has three times been J.D., Harvard University, 1940 designated as a “Distinguished Alumni Speaker” by Harvard Law School. -

Ronnie Eldridge Oral History Interview – RFK #1, 4/21/1970 Administrative Information

Ronnie Eldridge Oral History Interview – RFK #1, 4/21/1970 Administrative Information Creator: Ronnie Eldridge Interviewer: Roberta W. Greene Date of Interview: April 21, 1970 Length: 98 pages Biographical Note Eldridge, New York City district leader for the Reform Independent Democrats (1963- 1968) and vice chairperson of Citizen’s Committee for Robert F. Kennedy (1968), discusses Robert F. Kennedy’s (RFK) 1964 New York senatorial campaign, the 1966 New York surrogate court’s race, and Frank O’Connor’s 1966 gubernatorial campaign, among other issues. Access Open. Usage Restrictions According to the deed of gift signed October 21, 1994, copyright of these materials has been assigned to the United States Government. Users of these materials are advised to determine the copyright status of any document from which they wish to publish. Copyright The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research.” If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excesses of “fair use,” that user may be liable for copyright infringement. This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. The copyright law extends its protection to unpublished works from the moment of creation in a tangible form. -

Looking out for Our Members and the Community: Continued from P.1

JANUARY 2009 | VOL.24, NO.1 Looking out for our Members IN THIS ISSUE… and the Community Professional Development Workshop Series: PATRICIA M. HYNES, PRESIDENT The Essentials In good times and bad, the New York City Bar looks out for its members back page and contributes to the greater community. In 1946, a lot of Americans were resuming careers they had put on hold to serve in World War II, including Navigating Your Career lawyers seeking to return to their profession in a world with promise of an through Troubled economic boom getting underway. The question was how to connect the Waters – How to Turn returning lawyers to new and emerging opportunities. And so the City Bar, Crisis into Opportunity along with the New York County Lawyers’ Association, started the Legal page 10 Referral Service to help with career placement. City Bar Justice Again, during the downturn of the early 1990s, the Association invigorated its efforts to help Center’s Legal Clinic lawyers in transition to enhance their career opportunities. In that process, the City Bar built for the Homeless a series of programs that assist lawyers with their career options. page 6 Today, the Association is continuing its efforts to serve its members in difficult economic times. The Legal Referral Service is greatly expanded and continues to provide opportunities for experienced Will Compliance with attorneys to build their practice, as the accompanying article illustrates. We encourage our members International Law Make to apply to the Service to be included on its panels, because you never know when someone will call Us More Secure? looking for your practice area. -

Of Huge Revolutions Electrifying Timeto Be

Also inside | Interrogation Intelligence | Fighting Foreclosure | Souter’s Service Harvard Law Winter 2010 bulletin “I believe that this time will be known as an inflection point in world history because of huge revolutions under way in the world— changes that make this an electrifying time to be in the legal profession.” Martha Minow A Conversation with a New Dean c1_HLB_winter09_03.indd c1 12/15/09 10:44 AM IN THIS ISSUE Volume 61 Number 1 Winter 2010 14aPOINTS OF INFLECTION Five months into her new job, Dean Martha Minow shares some insights—and even a little advice. 20aA VIEW FROM THE BRINK When the financial system is melting down, who are you going to call? H. Rodgin Cohen ’68. 26aA QUESTION OF INTERROGATION Philip Heymann ’60 proposes a new model for intelligence gathering in the fight against terrorism. 30aTHE LAWS OF UNINTENDED CONSEQUENCES To prevent domestic violence, are we now overregulating the home? 35aSTRIVING ALWAYS TO GET IT RIGHT Reflections on David Souter ’66 1 FROM THE DEAN assistant dean for communications 2 LETTERS Robb London ’86 editor 3 HEARSAY Emily Newburger 4 OUTSIDE THE CLASSROOM managing editor A clinical project helps keep people Linda Grant in their homes. design director 8 ASK THE PROFESSOR Ronn Campisi editorial assistance How will globalization reshape the Asli Bashir, Stephanie Ehresman ’10, Jenny practice of law—and the training of Lackey, Lia Oppedisano, Christine Perkins, lawyers? Lori Ann Saslav, Marc Steinberg 11 ON THE BOOKSHELVES editorial office Harvard Law Bulletin Subramanian explores the messy 125 Mount Auburn St. middle ground in corporate deals; Cambridge, MA 02138 e-mail: [email protected] Fallon dives into fiction with a web site: www.law.harvard.edu/news/bulletin spoof on academics and politics. -

New York Criminal Law Newsletter a Publication of the Criminal Justice Section of the New York State Bar Association

NYSBA SPRING 2010 | VOL. 8 | NO. 2 New York Criminal Law Newsletter A publication of the Criminal Justice Section of the New York State Bar Association Inside Message from the Chair ..................................................................... 3 Illegal Immigration Undergoes Sharp Decline ...........................27 (James P. Subjack) New York Law Firms Experience Profi t Decline .........................28 Message from the Editor .................................................................... 4 Economic Decline Increases Food Stamp Recipients ..................28 (Spiros A. Tsimbinos) Value of Homes Has Experienced Signifi cant Decline ...............28 Feature Articles Isolationism Increases in U.S. .........................................................28 Recent Developments in Eyewitness Identifi cation OCA Chief Counsel Michael Colodner Retires ............................28 Expert Testimony ................................................................................5 Minority Representation Continues to Rise in New York (Peter Dunne) Law Firms ..........................................................................................28 In the Area of Eyewitness Identifi cation Expert Testimony, Americans Recouping Their Net Worth .......................................28 LeGrand Should Be Revisited ............................................................8 China Assumes World Leadership in Automobile Sales ............29 (Paul Shechtman) U.S. Prison Population Continues to Rise, New Trends in the Area of Criminal -

The Americans for Democratic Action Papers 1932-1965 '

The Americans for Democratic Action Papers 1932-1965 ' A GUIDE TO THE MICROFILM EDITION . ..... 'v1ty ~ -- • :::> Pro uesf Start here. This volume is a finding aid to a ProQuest Research Collection in Microform. To learn more visit: www.proquest.com or call (800) 521-0600 About ProQuest: ProQuest connects people with vetted, reliable information. Key to serious research, the company has forged a 70-year reputation as a gateway to the world's knowledge-from dissertations to governmental and cultural archives to news, in all its forms. Its role is essential to libraries and other organizations whose missions depend on the delivery of complete, trustworthy information. 789 E. Eisenhower Parkw~y • P.O Box 1346 • Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 • USA •Tel: 734.461.4700 • Toll-free 800-521-0600 • www.proquest.com AMERICANS FOR DEMOCRATIC ACTION PAPERS, 1932 - 1965 A GUIDE TO THE MICROFILM EDITION EDITED BY JACK T. ERICSON MICROFILMING CORPORATION OF AMERICA 1620 HAWKINS AVE./P. 0. BOX 10 SANFORD, NORTH CAROLINA 27330 1979 This guide accompanies the 142 reels that comprise the microfilm collection of materials published as Americans for Democratic Action Papers, 1932-1965. Information on the availability of this collection and the guide may be had by writing: Microfilming Corporation of America 1620 Hawkins Ave./P. o. Box 10 Sanford, North Carolina 27330 Copyright {£) 1979, Microfilming Corporation of America ISBN/0-667-00540-4 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE . v NOTE TO THE RESEARCHER vii HISTORY, DESCRIPTION OF ARRANGEMENT, AND REEL LIST SERIES l UDA ADMINISTRATIVE FILE, 1932-1951 l SERIES 2 ADA ADMINISTRATIVE FILE, 1946-1965 13 SERIES 3 ADA CHAPTER FILE, 1943-1965 .