Business Valuation Reports

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reform of the Elected Judiciary in Boss Tweed’S New York

File: 3 Lerner - Corrected from Soft Proofs.doc Created on: 10/1/2007 11:25:00 PM Last Printed: 10/7/2007 6:34:00 PM 2007] 109 FROM POPULAR CONTROL TO INDEPENDENCE: REFORM OF THE ELECTED JUDICIARY IN BOSS TWEED’S NEW YORK Renée Lettow Lerner* INTRODUCTION.......................................................................................... 111 I. THE CONSTITUTION OF 1846: POPULAR CONTROL...................... 114 II. “THE THREAT OF HOPELESS BARBARISM”: PROBLEMS WITH THE NEW YORK JUDICIARY AND LEGAL SYSTEM AFTER THE CIVIL WAR .................................................. 116 A. Judicial Elections............................................................ 118 B. Abuse of Injunctive Powers............................................. 122 C. Patronage Problems: Referees and Receivers................ 123 D. Abuse of Criminal Justice ............................................... 126 III. THE CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION OF 1867-68: JUDICIAL INDEPENDENCE............................................................. 130 A. Participation of the Bar at the Convention..................... 131 B. Natural Law Theories: The Law as an Apolitical Science ................................... 133 C. Backlash Against the Populist Constitution of 1846....... 134 D. Desire to Lengthen Judicial Tenure................................ 138 E. Ratification of the Judiciary Article................................ 143 IV. THE BAR’S REFORM EFFORTS AFTER THE CONVENTION ............ 144 A. Railroad Scandals and the Times’ Crusade.................... 144 B. Founding -

Supreme Court of the United States

1 SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES. Monday, October 13, 1902. The court met pursuant to law. Present : The Chief Justice, Mr. Justice Harlan, Mr. Justice Brewer, Mr. Justice Brown, Mr. Justice Shiras, Mr. Justice White, Mr. Justice Peckham and Mr. Justice McKenna. Warren K. Snyder of Oklahoma City, Okla., Joseph A. Burkart of Washington, D. C, Robert H. Terrell of Washington, D. C, Robert Catherwood of Chicago, 111., Sardis Summerfield of Reno, Nev., J. Doug- las Wetmore of Jacksonville, Fla., George D. Leslie of San Francisco, Cal., William R. Striugfellow of New Orleans, La., P. P. Carroll of Seattle, Wash., P. H. Coney of Topeka, Kans., H. M. Rulison of Cin- cinnati, Ohio, W^illiam Velpeau Rooker of Indianapolis, Ind., Isaac N. Huntsberger of Toledo, Ohio, and Charles W. Mullan of Waterloo, Iowa, were admitted to practice. The Chief Justice announced that all motions noticed for to-day would be heard to-morrow, and that the court would commence the call of the docket to-morrow pursuant to the twenty-sixth rule. Adjourned until to-morrow at 12 o'clock. The day call for Tuesday, October 14, will be as follows: Nos. 306, 303, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11 and 12. O 8753—02 1 2 SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES. Tuesday, October 14, 1902. Present: The Chief Justice, Mr. Justice Harlan, Mr. Justice Brewer, Mr. Justice Brown, Mr. Justice Shiras, Mr. Justice White, Mr. Justice Peckham and Mr. Justice McKenna. E. Howard McCaleb, jr., of New Orleans, La., Judson S. Hall of New York City, Elbert Campbell Ferguson of Chicago, 111., John Leland Manning of Chicago, 111., Alden B. -

NHB Regional Bee a JV Round #2

NHB Regional Bee A JV Round 2 NHB REGIONAL BEE A JV 1. This man was depicted as the Cowardly Lion from The Wizard of Oz during his 1900 campaign for president. Tom Watson was the Populist pick to run with this man in 1896, but Arthur Sewall appeared on his Democratic ballot. This man argued for the prosecution against Clarence Darrow during the Scopes Trial and spoke against the Coinage Act, saying that “they shall not crucify mankind upon” the title object. For the point, name this American politician who vocally opposed the gold standard in his “Cross of Gold” speech. ANSWER: William Jennings Bryan 134-11-61-02101 2. One battle during this conflict saw Samuel Appleton drive off attackers who had burned down most of the buildings in Springfield. Another battle during this conflict ended when Josiah Winslow’s militia overran an Indian fort and was known as the Great Swamp Battle. This war ended when Benjamin Church killed the opposing side’s leader. For the point, name this war, which was fought between colonists and Native Americans led by a namesake Wampanoag chief. ANSWER: King Philip’s War [or Metacomet’s War; accept Metacomet’s Rebellion] 140-11-61-02102 3. This man opposed the New York political machine by appointing Wheeler Hazard Peckham to the Supreme Court. One movement during his term opposed the national roads program and was stopped on the grass of the Capitol. This man stopped another protest with federal troops because it was blocking the mail. Those events, Coxey’s Army and the Pullman Strike, were responses to the Panic of 1873 during his term. -

Table of Contents

T a b l e C o n T e n T s I s s u e 9 s u mm e r 2 0 1 3 o f pg 4 pg 18 pg 26 pg 43 Featured articles Pg 4 abraham lincoln and Freedom of the Press A Reappraisal by Harold Holzer Pg 18 interbranch tangling Separating Our Constitutional Powers by Judith s. Kaye Pg 26 rutgers v. Waddington Alexander Hamilton and the Birth Pangs of Judicial Review by David a. Weinstein Pg 43 People v. sanger and the Birth of Family Planning clinics in america by Maria T. Vullo dePartments Pg 2 From the executive director Pg 58 the david a. Garfinkel essay contest Pg 59 a look Back...and Forward Pg 66 society Officers and trustees Pg 66 society membership Pg 70 Become a member Back inside cover Hon. theodore t. Jones, Jr. In Memoriam Judicial Notice l 1 From the executive director udicial Notice is moving forward! We have a newly expanded board of editors Dearwho volunteer Members their time to solicit and review submissions, work with authors, and develop topics of legal history to explore. The board of editors is composed J of Henry M. Greenberg, Editor-in-Chief, John D. Gordan, III, albert M. rosenblatt, and David a. Weinstein. We are also fortunate to have David l. Goodwin, Assistant Editor, who edits the articles and footnotes with great care and knowledge. our own Michael W. benowitz, my able assistant, coordinates the layout and, most importantly, searches far and wide to find interesting and often little-known images that greatly compliment and enhance the articles. -

Extensions of Remarks E356 HON. ALAN S. LOWENTHAL HON

E356 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks March 21, 2017 NATIONAL ROSIE THE RIVETER IN HONOR OF ALABAMA STATE I honor all of the work Kitty accomplished in DAY: A TRIBUTE TO THE LONG UNIVERSITY’S WAR GARDENS our community and the trail she blazed for the BEACH ROSIE THE RIVETER women inspired by her achievements. PARK HON. MARTHA ROBY f OF ALABAMA PERSONAL EXPLANATION HON. ALAN S. LOWENTHAL IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Tuesday, March 21, 2017 HON. LUIS V. GUTIE´RREZ OF CALIFORNIA Mrs. ROBY. Mr. Speaker, I rise today to OF ILLINOIS IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES honor Alabama State University upon its 100 IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES year anniversary of planting war gardens to Tuesday, March 21, 2017 Tuesday, March 21, 2017 aid the United States efforts in World War I. Mr. GUTIE´ RREZ. Mr. Speaker, I was un- Mr. LOWENTHAL. Mr. Speaker, I am a One hundred years ago, students, staff, and avoidably absent in the House chamber for roll proud co-sponsor of House Resolution 162, faculty of the then State Normal School at call votes 173, 174, 175 on Monday, March which will designate March 21, 2017, as Na- Montgomery, subsequently Alabama State 20, 2017. Had I been present, I would have tional Rosie the Riveter Day. This honor has University, assisted and advised residents voted ‘‘Yea’’ on roll call votes 173, 174, and special significance for the City of Long near campus and in the City of Montgomery, 175. Beach, California which I represent. Alabama on how to plant war gardens. Thanks f to these efforts, it was reported that in March Long Beach is one of two locations in the 1918 over 1,400 black homes in Montgomery SPECIAL TRIBUTE IN HONOR OF nation that has a park dedicated to recog- had war gardens. -

“But How Are Their Decisions to Be Known?” 1 Johnson’S Reports Iv

★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ “But how are their decisions to be known?” 1 Johnson’s Reports iv CELEBRATING 200 Years of New York State Official Law Reporting “But how are their decisions to be known?” “ We must look . to our own courts, for those precedents which have the binding force of authority and law. But how are their decisions to be known? Must they float in the memories of those by whom they are pronounced, and the law, instead of being a fixed and uniform rule of action, be thus subject to perpetual fluctuation and change? No man doubts of the propriety or necessity of publishing the acts of the legislature. As the rights and interests of every individual may be equally affected by the decisions of our courts, one would naturally imagine, that it would be equally a matter of public concern, that they should be made known in some authentic manner to the community.” 1 Johnson’s Reports iv-v NEW YORK STATE ANNIVERSARY BOOKLET LAW REPORTING BUREAU COMMITTEE One Commerce Plaza, Suite 1750 Charles A. Ashe Albany, N.Y. 12210 (518) 474-8211 Maureen L. Clements www.courts.state.ny.us/reporter William J. Hooks Gary D. Spivey State Reporter Katherine D. LaBoda Charles A. Ashe Chilton B. Latham Deputy State Reporter John W. Lesniak William J. Hooks Cynthia McCormick Assistant State Reporter Michael S. Moran Production of this booklet coordinated by: Gail A. Nassif Michael S. Moran Katherine D. LaBoda Gayle M. Palmer Graphic design by: Gary D. Spivey Jeanne Otto of West, a Thomson Company On the Cover: The “Old Hun Building,” on the left, 25 North Pearl St., Albany, N.Y. -

Impersonal Names Index Listing for the INSCOM Investigative Records Repository, 2010

Description of document: US Army Intelligence and Security Command (INSCOM) Impersonal Names Index Listing for the INSCOM Investigative Records Repository, 2010 Requested date: 07-August-2010 Released date: 15-August-2010 Posted date: 23-August-2010 Title of document Impersonal Names Index Listing Source of document: Commander U.S. Army Intelligence & Security Command Freedom of Information/Privacy Office ATTN: IAMG-C-FOI 4552 Pike Road Fort George G. Meade, MD 20755-5995 Fax: (301) 677-2956 Note: The IMPERSONAL NAMES index represents INSCOM investigative files that are not titled with the name of a person. Each item in the IMPERSONAL NAMES index represents a file in the INSCOM Investigative Records Repository. You can ask for a copy of the file by contacting INSCOM. The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. -

The Common Law Powers of the New York State Attorney General

THE COMMON LAW POWERS OF THE NEW YORK STATE ATTORNEY GENERAL Bennett Liebman* The role of the Attorney General in New York State has become increasingly active, shifting from mostly defensive representation of New York to also encompass affirmative litigation on behalf of the state and its citizens. As newly-active state Attorneys General across the country begin to play a larger role in national politics and policymaking, the scope of the powers of the Attorney General in New York State has never been more important. This Article traces the constitutional and historical development of the At- torney General in New York State, arguing that the office retains a signifi- cant body of common law powers, many of which are underutilized. The Article concludes with a discussion of how these powers might influence the actions of the Attorney General in New York State in the future. INTRODUCTION .............................................. 96 I. HISTORY OF THE OFFICE OF THE NEW YORK STATE ATTORNEY GENERAL ................................ 97 A. The Advent of Affirmative Lawsuits ............. 97 B. Constitutional History of the Office of Attorney General ......................................... 100 C. Statutory History of the Office of Attorney General ......................................... 106 II. COMMON LAW POWERS OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL . 117 A. Historic Common Law Powers of the Attorney General ......................................... 117 B. The Tweed Ring and the Attorney General ....... 122 C. Common Law Prosecutorial Powers of the Attorney General ................................ 126 D. Non-Criminal Common Law Powers ............. 136 * Bennett Liebman is a Government Lawyer in Residence at Albany Law School. At Albany Law School, he has served variously as the Executive Director, the Acting Director and the Interim Director of the Government Law Center. -

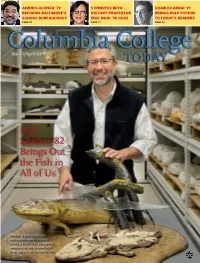

Neil Shubin '82 Brings out the Fish in All of Us

ANDRES ALONSO ’79 5 MINUTES WITH … CHARLES ARDAI ’91 REFORMS BALTIMORE’S HISTORY PROFESSOR BRINGS PULP FICTION SCHOOL BUREAUCRACY MAE NGAI ’98 GSAS TO TODAY’S READERS PAGE 22 PAGE 11 PAGE 24 Columbia College March/April 2011 TODAY Neil Shubin ’82 Brings Out the Fish in All of Us Shubin, a paleontologist and evolutionary biologist, co-led a team that discovered evidence of the pivotal shift from aquatic to terrestrial life. ust another J membership perk. Meet. Dine. Entertain. Join the Columbia Club and access state-of-the-art meeting rooms for your conferences and events. For more information or to apply, visit www.columbiaclub.org or call (212) 719-0380. The Columbia University Club of New York in residence at 15 West 43 St. New York, N Y 10036 Columbia’s SocialIntellectualCulturalRecreationalProfessional Resource in Midtown. Columbia College Today Contents 22 12 24 7 56 18 COVER STORY ALUMNI NEWS DEPARTMENTS G O FISH 27 O BITUARIES 2 LETTERS TO THE 12 Paleontologist and evolutionary biologist Neil Shubin 27 Joseph D. Coffee Jr. ’41 EDITOR ’82 brings out the fish in all of us. 28 Garland E. Wood ’65 3 ITHIN THE AMILY By Nathalie Alonso ’08 W F 30 B OOKSHEL F 4 AROUND THE QUADS FEATURES Featured: Adam Gidwitz ’04 4 turns classic folklore on its Northwest Corner Building Opens COLUMBIA FORUM ear with his new children’s 18 book, A Tale Dark & Grimm. 5 Rose, Jones Join In an excerpt from his book How Soccer Explains the College Senior Staff World: An Unlikely Theory of Globalization, Franklin 32 LASS OTES 6 Creed To Deliver Foer ’96 explains how one soccer club’s destiny was C N A LUMNI PRO F ILES Class Day Address shaped by European anti-Semitism. -

History of the U.S. Attorneys

Bicentennial Celebration of the United States Attorneys 1789 - 1989 "The United States Attorney is the representative not of an ordinary party to a controversy, but of a sovereignty whose obligation to govern impartially is as compelling as its obligation to govern at all; and whose interest, therefore, in a criminal prosecution is not that it shall win a case, but that justice shall be done. As such, he is in a peculiar and very definite sense the servant of the law, the twofold aim of which is that guilt shall not escape or innocence suffer. He may prosecute with earnestness and vigor– indeed, he should do so. But, while he may strike hard blows, he is not at liberty to strike foul ones. It is as much his duty to refrain from improper methods calculated to produce a wrongful conviction as it is to use every legitimate means to bring about a just one." QUOTED FROM STATEMENT OF MR. JUSTICE SUTHERLAND, BERGER V. UNITED STATES, 295 U. S. 88 (1935) Note: The information in this document was compiled from historical records maintained by the Offices of the United States Attorneys and by the Department of Justice. Every effort has been made to prepare accurate information. In some instances, this document mentions officials without the “United States Attorney” title, who nevertheless served under federal appointment to enforce the laws of the United States in federal territories prior to statehood and the creation of a federal judicial district. INTRODUCTION In this, the Bicentennial Year of the United States Constitution, the people of America find cause to celebrate the principles formulated at the inception of the nation Alexis de Tocqueville called, “The Great Experiment.” The experiment has worked, and the survival of the Constitution is proof of that. -

Judicial Opinion Writing: Gerald Lebovits

JUDICIAL OPINION WRITING For State Tax Judges October 12, 2018 Chicago, Illinois GERALD LEBOVITS Acting Justice, NYS Supreme Court Adjunct Professor of Law, Columbia Law School Adjunct Professor of Law, Fordham University School of Law Adjunct Professor of Law, New York University School of Law Judicial Opinion Writing For State Tax Judges October 12, 2018 By: Gerald Lebovits Table of Contents Gerald Lebovits, Alifya V. Curtin & Lisa Solomon, Ethical Judicial Opinion Writing, 21 Geo. J. Legal Ethics 237 (2008).................................................................................... A Gerald Lebovits, The Legal Writer, Ethical Judicial Writing—Part I, 78 N.Y. St. B.J. 64 (Nov./Dec. 2006) ................................................................................. B Gerald Lebovits, The Legal Writer, Ethical Judicial Writing—Part II, 79 N.Y. St. B.J. 64 (Jan. 2007) ........................................................................................... C Gerald Lebovits, The Legal Writer, Ethical Judicial Writing—Part III, 79 N.Y. St. B.J. 64 (Feb. 2007)........................................................................................... D Gerald Lebovits, The Legal Writer, Legal-Writing Ethics—Part I, 77 N.Y. St. B.J. 64 (Oct. 2005) ........................................................................................... E Gerald Lebovits, The Legal Writer, Legal-Writing Ethics—Part II, 77 N.Y. St. B.J. 64 (Nov./Dec. 2005) ................................................................................. F Gerald -

14Th Amendment US Constitution

FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT RIGHTS GUARANTEED PRIVILEGES AND IMMUNITIES OF CITIZENSHIP, DUE PROCESS AND EQUAL PROTECTION CONTENTS Page Section 1. Rights Guaranteed ................................................................................................... 1565 Citizens of the United States ............................................................................................ 1565 Privileges and Immunities ................................................................................................. 1568 Due Process of Law ............................................................................................................ 1572 The Development of Substantive Due Process .......................................................... 1572 ``Persons'' Defined ................................................................................................. 1578 Police Power Defined and Limited ...................................................................... 1579 ``Liberty'' ................................................................................................................ 1581 Liberty of Contract ...................................................................................................... 1581 Regulatory Labor Laws Generally ...................................................................... 1581 Laws Regulating Hours of Labor ........................................................................ 1586 Laws Regulating Labor in Mines .......................................................................