Ronnie Eldridge Oral History Interview – RFK #1, 4/21/1970 Administrative Information

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table of Contents

T a b l e C o n T e n T s I s s u e 9 s u mm e r 2 0 1 3 o f pg 4 pg 18 pg 26 pg 43 Featured articles Pg 4 abraham lincoln and Freedom of the Press A Reappraisal by Harold Holzer Pg 18 interbranch tangling Separating Our Constitutional Powers by Judith s. Kaye Pg 26 rutgers v. Waddington Alexander Hamilton and the Birth Pangs of Judicial Review by David a. Weinstein Pg 43 People v. sanger and the Birth of Family Planning clinics in america by Maria T. Vullo dePartments Pg 2 From the executive director Pg 58 the david a. Garfinkel essay contest Pg 59 a look Back...and Forward Pg 66 society Officers and trustees Pg 66 society membership Pg 70 Become a member Back inside cover Hon. theodore t. Jones, Jr. In Memoriam Judicial Notice l 1 From the executive director udicial Notice is moving forward! We have a newly expanded board of editors Dearwho volunteer Members their time to solicit and review submissions, work with authors, and develop topics of legal history to explore. The board of editors is composed J of Henry M. Greenberg, Editor-in-Chief, John D. Gordan, III, albert M. rosenblatt, and David a. Weinstein. We are also fortunate to have David l. Goodwin, Assistant Editor, who edits the articles and footnotes with great care and knowledge. our own Michael W. benowitz, my able assistant, coordinates the layout and, most importantly, searches far and wide to find interesting and often little-known images that greatly compliment and enhance the articles. -

9. Memorandum of a Meeting with President Kennedy Prepared by CIA Director Mccone at • of Ind JFK and His CIA Director Discuss the Right Tack to Take with Castro

1963: Old Tactics, New Approaches 315 criticism from certain quarters in this country.5 But neither such criticism nor er to the opposition of any sector of our society will be allowed to determine the poli- rpre- cies of this Government. In particular, I have neither the intention nor the de- This sire to invade Cuba; I consider that it is for the Cuban people themselves to niest decide their destiny. I am determined to continue with policies which will con- tribute to peace in the Caribbean.6... There are other issues and problems before us, but perhaps I have said enough to give you a sense of my own current thinking on these matters. Let me now also offer the suggestion that it might be helpful if some time in May I should send a senior personal representative to discuss these and other matters informally with you. The object would not be formal negotiations, but a fully frank, informal exchange of views, arranged in such a way as to receive as little attention as possible. If this thought is appealing to you, please let me know your views on the most convenient time. In closing, I want again to send my warm personal wishes to you and all your family. These are difficult and dangerous times in which we live, and both you and I have grave responsibilities to our families and to all of mankind. The pres- sures from those who have a less patient and peaceful outlook are very great— but I assure you of my own determination to work at all times to strengthen world peace. -

1980 Commencement Program New York Law School

digitalcommons.nyls.edu NYLS Publications Commencement Programs 6-1-1980 1980 Commencement Program New York Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/commencement_progs NEW YORK LAW SCHOOL Eighty- Eighth Commencement Exercises June 1, 1980 AVERY FISHER HALL Lincoln Center New York, New York BOARD OF TRUSTEES John V. Thornton, Chairman of the Board Senior Vice President-Finance, Consolidated Edison Co., Inc. Charles W. Froessel '13, Honorary Chairman of the Board Trustee Emeritus Associate Judge, New York State Court of Appeals, 1950-1962 David Finkelstein, Vice Chairman Chairman of the Executive Committee and General Counsel Bates Manufacturing Company, Incorporated Alfred J. Bohlinger '24, Trustee Emeritus Superintendent oflnsurance, State of New York, 1950-1955 A.H. Brawner, Jr. Executive Vice President, Toronto Dominion Bank of California Chairman, Executive Committee, Brandon Applied Systems, Inc. Barbara Debs President, Manhattanville College Jerry Finkelstein '38, Trustee Emeritus Publisher, New York Law Journal Sylvia D. Garland '60 Partner, Hofheimer Gartlir Gottlieb & Gross Immediate Past President, New York Law School Alumni Association Maurice R. Greenberg 'SO President, American International (Ins.) Group, Inc. Alfred Gross, Trustee Emeritus Trustee, Horace Mann School Walter M. Jeffords, Jr. Chairman of the Board, Northern Utilities, Inc. William Kapelman '40 Assistant Administrative Judge, Bronx County Supreme Court, State of New York President, New York Law School Alumni Association Samuel J. LeFrak Chairman of the Board, Lefrak Organization, Inc. Hon. Francis T. Murphy '52 Presiding Justice, Appellate Division, First Department Supreme Court, State of New York Vice President, New York Law School Alumni Association John J. Navin, Jr. Vice President, Corporate Counsel and Secretary, ITT Corp. -

Extensions of Remarks E356 HON. ALAN S. LOWENTHAL HON

E356 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks March 21, 2017 NATIONAL ROSIE THE RIVETER IN HONOR OF ALABAMA STATE I honor all of the work Kitty accomplished in DAY: A TRIBUTE TO THE LONG UNIVERSITY’S WAR GARDENS our community and the trail she blazed for the BEACH ROSIE THE RIVETER women inspired by her achievements. PARK HON. MARTHA ROBY f OF ALABAMA PERSONAL EXPLANATION HON. ALAN S. LOWENTHAL IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Tuesday, March 21, 2017 HON. LUIS V. GUTIE´RREZ OF CALIFORNIA Mrs. ROBY. Mr. Speaker, I rise today to OF ILLINOIS IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES honor Alabama State University upon its 100 IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES year anniversary of planting war gardens to Tuesday, March 21, 2017 Tuesday, March 21, 2017 aid the United States efforts in World War I. Mr. GUTIE´ RREZ. Mr. Speaker, I was un- Mr. LOWENTHAL. Mr. Speaker, I am a One hundred years ago, students, staff, and avoidably absent in the House chamber for roll proud co-sponsor of House Resolution 162, faculty of the then State Normal School at call votes 173, 174, 175 on Monday, March which will designate March 21, 2017, as Na- Montgomery, subsequently Alabama State 20, 2017. Had I been present, I would have tional Rosie the Riveter Day. This honor has University, assisted and advised residents voted ‘‘Yea’’ on roll call votes 173, 174, and special significance for the City of Long near campus and in the City of Montgomery, 175. Beach, California which I represent. Alabama on how to plant war gardens. Thanks f to these efforts, it was reported that in March Long Beach is one of two locations in the 1918 over 1,400 black homes in Montgomery SPECIAL TRIBUTE IN HONOR OF nation that has a park dedicated to recog- had war gardens. -

Resolving the Debate on Public Funding for National Public Radio

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Seton Hall University Libraries GIAROLO_PUBLIC BROADCASTING 4/30/2013 8:27 AM Resolving the Debate on Public Funding for National Public Radio Andrew Giarolo* INTRODUCTION ......................................................................... 440 IN THE BEGINNING, ALL WAS DARKNESS ................................. 441 A. The Public Broadcasting Act of 1964 ....................... 442 B. The Attacks Begin; NPR Takes Action .................... 445 ALTERNATIVE SOLUTIONS ........................................................ 447 Alternative I: Revive the Fairness Doctrine ................. 447 Alternative II: Implement the Fairness Doctrine Solely for All Federally-Funded Programs so that Allegations of Bias Can Be Minimized ................... 452 Alternative III: Direct Broadcast License Fees Directly to an Independent, Regulatory Trustee that Directly Subsidizes Public Broadcasting ........ 455 CONCLUSION ............................................................................ 459 * J.D. Candidate 2013, Seton Hall University School of Law. The author wishes to thank Professor Ronald Riccio for valuable input and his loving wife, Laura, for her support and the temporary loan of her great intellect and common sense. 439 GIAROLO_PUBLIC BROADCASTING 4/30/2013 8:27 AM 440 Seton Hall Journal of Sports and Entertainment Law [Vol. 23.2 It is axiomatic that one of the most vital questions of mass communication in a democracy is the development of an informed public opinion through the public dissemination of news and ideas concerning the vital public issues of the day. It is the right of the public to be informed, rather than any right on the part of the Government, any broadcast licensee or any individual member of the public to broadcast his own particular views on any matter, which is the foundation stone of the American system of broadcasting.1 INTRODUCTION Public funding for National Public Radio (“NPR”) has come under fire, yet again. -

Impersonal Names Index Listing for the INSCOM Investigative Records Repository, 2010

Description of document: US Army Intelligence and Security Command (INSCOM) Impersonal Names Index Listing for the INSCOM Investigative Records Repository, 2010 Requested date: 07-August-2010 Released date: 15-August-2010 Posted date: 23-August-2010 Title of document Impersonal Names Index Listing Source of document: Commander U.S. Army Intelligence & Security Command Freedom of Information/Privacy Office ATTN: IAMG-C-FOI 4552 Pike Road Fort George G. Meade, MD 20755-5995 Fax: (301) 677-2956 Note: The IMPERSONAL NAMES index represents INSCOM investigative files that are not titled with the name of a person. Each item in the IMPERSONAL NAMES index represents a file in the INSCOM Investigative Records Repository. You can ask for a copy of the file by contacting INSCOM. The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. -

Frank Mankiewicz Oral History Interview – RFK #2, 7/10/1969

Frank Mankiewicz Oral History Interview – RFK #3, 8/12/1969 Administrative Information Creator: Frank Mankiewicz Interviewer: Larry J. Hackman Date of Interview: August 12, 1969 Place of Interview: Bethesda, Maryland Length: 91 pp. Biographical Note Mankiewicz was director of the Peace Corps in Lima, Peru from 1962 to 1964, Latin America regional director from 1964 to 1966 and then press secretary to Senator Robert F. Kennedy from 1966 to 1968. In the interview Mankiewicz discusses Robert Kennedy’s relationship with President Johnson and the Johnson administration, the foreign and domestic press, Robert Kennedy’s speech on Vietnam and campaigning, among other issues. Access Restrictions No restrictions. Usage Restrictions According to the deed of gift signed March 1, 2000, copyright of these materials has been assigned to the United States Government. Copyright The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research.” If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excesses of “fair use,” that user may be liable for copyright infringement. This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. The copyright law extends its protection to unpublished works from the moment of creation in a tangible form. -

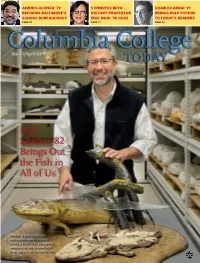

Neil Shubin '82 Brings out the Fish in All of Us

ANDRES ALONSO ’79 5 MINUTES WITH … CHARLES ARDAI ’91 REFORMS BALTIMORE’S HISTORY PROFESSOR BRINGS PULP FICTION SCHOOL BUREAUCRACY MAE NGAI ’98 GSAS TO TODAY’S READERS PAGE 22 PAGE 11 PAGE 24 Columbia College March/April 2011 TODAY Neil Shubin ’82 Brings Out the Fish in All of Us Shubin, a paleontologist and evolutionary biologist, co-led a team that discovered evidence of the pivotal shift from aquatic to terrestrial life. ust another J membership perk. Meet. Dine. Entertain. Join the Columbia Club and access state-of-the-art meeting rooms for your conferences and events. For more information or to apply, visit www.columbiaclub.org or call (212) 719-0380. The Columbia University Club of New York in residence at 15 West 43 St. New York, N Y 10036 Columbia’s SocialIntellectualCulturalRecreationalProfessional Resource in Midtown. Columbia College Today Contents 22 12 24 7 56 18 COVER STORY ALUMNI NEWS DEPARTMENTS G O FISH 27 O BITUARIES 2 LETTERS TO THE 12 Paleontologist and evolutionary biologist Neil Shubin 27 Joseph D. Coffee Jr. ’41 EDITOR ’82 brings out the fish in all of us. 28 Garland E. Wood ’65 3 ITHIN THE AMILY By Nathalie Alonso ’08 W F 30 B OOKSHEL F 4 AROUND THE QUADS FEATURES Featured: Adam Gidwitz ’04 4 turns classic folklore on its Northwest Corner Building Opens COLUMBIA FORUM ear with his new children’s 18 book, A Tale Dark & Grimm. 5 Rose, Jones Join In an excerpt from his book How Soccer Explains the College Senior Staff World: An Unlikely Theory of Globalization, Franklin 32 LASS OTES 6 Creed To Deliver Foer ’96 explains how one soccer club’s destiny was C N A LUMNI PRO F ILES Class Day Address shaped by European anti-Semitism. -

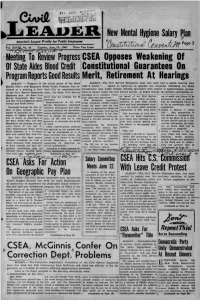

Meeting to Review Progress of State Aides Blood Credit Program

Hi ' SHUOlrlW^ Pl ni'NGSV ^SH.iAuia • ' nonan' ' AUVD BHMBi ^^^ ^ ^r^ V • .md •NObN i nci - liEAUER New Mental Hygiene Salary ^Jan America't Largett Weekly for Public Employee* iVol. XXVllIv,No. 41 Tuesday, June. 13, 1967 Price Ten Cents Meeting To Review Progress CSEA Opposes Weakening Of Of State Aides Blood Credit Constitutional Guarantees On Program Reports Good Results Merit, Retirement At Hearings ALBANY — Progress in the initial phase of the State ALBANY—^The Civil Service Employees Assn. last week told a public hearing here Health Plan's new Employee Blood Credit Program was re- that It would . oppose as vigorously as possible any language amending the State viewed at a meeting in New York City by representatives Constitution that might weaken existing provisions with respect to appointments, promo- of the Civil Service Employees Assn., the State Civil Service tions or tenure under the civil service system, or might change the present contractual re- lationship of its members' retire- Employees Assn., the State Civil on behalf of the Civil Service ing to merit and fitness to ba dence that the program will be ment plans and guarantees." Service Department, Blue Cross, Employees Assn. which, as repre- ascertained as far as practic- successful. The Employees Association, and New York's Community Blood sentative of more than 150,000 able, by examination which, as Representatives of the Civil which represents 150,000 workers Council and Blood Center. State and local government work- as far as practicable, shall be Service Department introduced within the State, took the firm ers, is the largest public employee competitive.' Developed through the joint ef- tentative promotional and infor- stand In an appearance before the organization in New York State. -

The Formation of Robert F. Kennedy and Cesar Chavez's Bond

Robert F. Kennedy and the Farmworkers: The Formation of Robert F. Kennedy and Cesar Chavez’s Bond By Mariah Kennedy Cuomo Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts In the Department of History at Brown University Thesis Advisor: Edward L. Widmer April 7, 2017 !1 Acknowledgements I would like to thank all who made this work possible. Writing this thesis was a wonderful experience because of the incredible and inspirational stories of Robert F. Kennedy and Cesar Chavez, and also because of the enthusiasm those around me have for the topic. I would first like to thank Robert F. Kennedy and Cesar Chavez for their lasting impact on our country, and for the inspiration they provide to live with compassion. I would also like to thank the farm workers, for their heroism and strength in their fight for justice. I also would like to thank my thesis advisor, Ted Widmer, for his ongoing support throughout writing my thesis. Thank you for always pushing me to think deeper, and for helping me to discover new insights. Thank you to Ethan Pollock, for providing me with the tools to undertake this mission. Thank you to my mother, Kerry Kennedy, for inspiring me to take on this topic with the amazing work you do—you too, are an inspiration to me. Thank you for your ongoing guidance. Thank you to Marc Grossman, who was an amazing help and provided invaluable assistance in making this piece historically accurate. And finally, thank you to the incredible participants in the farm worker movement who took the time to speak with me. -

William F. Haddad Interviewer: Larry J

William F. Haddad Oral History Interview – RFK, 02/27/1969 Administrative Information Creator: William F. Haddad Interviewer: Larry J. Hackman Date of Interview: February 27, 1969 Place of Interview: New York, New York Length: 35 pages Biographical Note Haddad was the Associate Director, Inspector General of the Peace Corps, 1961-1963; Special Assistant to Robert F. Kennedy, 1960 Presidential Campaign; Campaign Advisor Robert F. Kennedy for President, 1968. In this interview, he discusses his work on the campaigns of multiple politicians, the organizing of Robert Kennedy’s 1968 presidential campaign, and RFK’s strengths as a political leader, among other issues. Access Open Usage Restrictions According to the deed of gift signed June 5, 2002, copyright of these materials has been assigned to the United States Government. Users of these materials are advised to determine the copyright status of any document from which they wish to publish. Copyright The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research.” If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excesses of “fair use,” that user may be liable for copyright infringement. This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. -

U.S.-Cuban Talks in '63 Described

urinal states aeregate to the United Nations, the late Adlai 1 E. Stevenson, and to Ambas- -U.S.-CUBAN TALKS sador W. Averell Harriman. He added: "On Sept. 19, Harriman. told IN '63 DESCRIBED me he was "advmoz.esome' 0, 12,nilx.41 :/4 enough to favor the idea, but suggested I discuss it with Bob ,Book SeesKennedyC ut Kennedy because of-it5•polbtical on Castro Move for Ties iniplications. Stevenson, mein while, had mentioned it 'to.the President, who' approved t talking to Dr. Carlos 'Ledhuga, By HENRY RAYMONT the chief Cuban delegate; so A detailed account of Presi- long as I made it clear we were dent Kennedy's cautious but not soliciting discussions.", favorable response to overtures Terms Not Proposed by Premier Fidel Castro of Cu- Mr. Attwood suggested that ba for,, a resumption of diplo- the AdministratiCor never . ex- matic relations is disclosed in a plicitly proposed the terms of a. book to be published this month. settlement beyond . reiterating The secret diplomatic ex- its official position, that. Pre- changes between the two Gov- mier Castro should sever • all military ties with the Soviet ernments began in September, Union and Peking and renounce 1963, and ended with Mr. Ken- his proclaimed attempts to.sub- nedy's assassination. vert 'other Latin-American, gciv- Long withheld by fetiner ernnients. members of the Kennedy Ad: However, the book'' strongly suggests that the Kennedy Ad- WIUL ur. iscnuga, who ministration, the details of the ministration agreed . with his confidential talks appear in has- since been shifted to the estimate that a deal- was pos- Cuban Ministry of Culture, he "The Reds and the Blacks" by sible.