Radical Chic: That Party at Lenny’S “

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1980 Commencement Program New York Law School

digitalcommons.nyls.edu NYLS Publications Commencement Programs 6-1-1980 1980 Commencement Program New York Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/commencement_progs NEW YORK LAW SCHOOL Eighty- Eighth Commencement Exercises June 1, 1980 AVERY FISHER HALL Lincoln Center New York, New York BOARD OF TRUSTEES John V. Thornton, Chairman of the Board Senior Vice President-Finance, Consolidated Edison Co., Inc. Charles W. Froessel '13, Honorary Chairman of the Board Trustee Emeritus Associate Judge, New York State Court of Appeals, 1950-1962 David Finkelstein, Vice Chairman Chairman of the Executive Committee and General Counsel Bates Manufacturing Company, Incorporated Alfred J. Bohlinger '24, Trustee Emeritus Superintendent oflnsurance, State of New York, 1950-1955 A.H. Brawner, Jr. Executive Vice President, Toronto Dominion Bank of California Chairman, Executive Committee, Brandon Applied Systems, Inc. Barbara Debs President, Manhattanville College Jerry Finkelstein '38, Trustee Emeritus Publisher, New York Law Journal Sylvia D. Garland '60 Partner, Hofheimer Gartlir Gottlieb & Gross Immediate Past President, New York Law School Alumni Association Maurice R. Greenberg 'SO President, American International (Ins.) Group, Inc. Alfred Gross, Trustee Emeritus Trustee, Horace Mann School Walter M. Jeffords, Jr. Chairman of the Board, Northern Utilities, Inc. William Kapelman '40 Assistant Administrative Judge, Bronx County Supreme Court, State of New York President, New York Law School Alumni Association Samuel J. LeFrak Chairman of the Board, Lefrak Organization, Inc. Hon. Francis T. Murphy '52 Presiding Justice, Appellate Division, First Department Supreme Court, State of New York Vice President, New York Law School Alumni Association John J. Navin, Jr. Vice President, Corporate Counsel and Secretary, ITT Corp. -

Radical Chic? Yes We Are!

Radical Chic? Yes We Are! Johan Frederik Hartle 23 March 2012 Ever since Tom Wolfe in a classical 1970 essay coined the term "radical chic", upper-class flirtation with radical causes has been ridiculed. But by separating aesthetics from politics Wolfe was actually more reactionary than the people he criticized, writes Johan Frederik Hartle. Even the most practical revolutionaries will be found to have manifested their ideas in the aesthetic sphere. Kenneth Burke, 1936 Newness and the aesthetico-political A discussion of “radical chic” – a term used to denounce criticism and radical thought as something merely fashionable – is, to some extent, a discussion of the new. And while the merely fashionable is, in spite of its pretensions to be innovative and new, still conformist and predictable, being radical is the (sometimes tragic) attempt to differ. Such attempts to differ from prevailing (complacent, bourgeois) agreements are strongly dependent on the jargon of novelty. Therefore we find overlapping dimensions of the aesthetic and the political in the concept of the new. The new itself, a key concept of aesthetic modernity, however, has not always been fashionable. And the category of the new is of course nothing new itself. The new fills archives, whole libraries – and that is, somehow, a paradox in itself. Generations of modernist aestheticians were dealing with the question: why is there aesthetic innovation at all, and how is it possible? With the post-historical exhaustion of history the rejection of the new was cause for a certain satisfaction. Boris Groys argues that: the discourse on the impossibility of the new in art has become especially widespread and influential. -

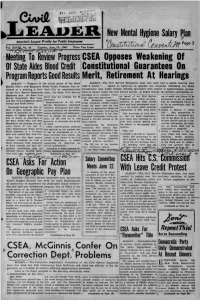

Meeting to Review Progress of State Aides Blood Credit Program

Hi ' SHUOlrlW^ Pl ni'NGSV ^SH.iAuia • ' nonan' ' AUVD BHMBi ^^^ ^ ^r^ V • .md •NObN i nci - liEAUER New Mental Hygiene Salary ^Jan America't Largett Weekly for Public Employee* iVol. XXVllIv,No. 41 Tuesday, June. 13, 1967 Price Ten Cents Meeting To Review Progress CSEA Opposes Weakening Of Of State Aides Blood Credit Constitutional Guarantees On Program Reports Good Results Merit, Retirement At Hearings ALBANY — Progress in the initial phase of the State ALBANY—^The Civil Service Employees Assn. last week told a public hearing here Health Plan's new Employee Blood Credit Program was re- that It would . oppose as vigorously as possible any language amending the State viewed at a meeting in New York City by representatives Constitution that might weaken existing provisions with respect to appointments, promo- of the Civil Service Employees Assn., the State Civil Service tions or tenure under the civil service system, or might change the present contractual re- lationship of its members' retire- Employees Assn., the State Civil on behalf of the Civil Service ing to merit and fitness to ba dence that the program will be ment plans and guarantees." Service Department, Blue Cross, Employees Assn. which, as repre- ascertained as far as practic- successful. The Employees Association, and New York's Community Blood sentative of more than 150,000 able, by examination which, as Representatives of the Civil which represents 150,000 workers Council and Blood Center. State and local government work- as far as practicable, shall be Service Department introduced within the State, took the firm ers, is the largest public employee competitive.' Developed through the joint ef- tentative promotional and infor- stand In an appearance before the organization in New York State. -

Ursula Mctaggart

RADICALISM IN AMERICA’S “INDUSTRIAL JUNGLE”: METAPHORS OF THE PRIMITIVE AND THE INDUSTRIAL IN ACTIVIST TEXTS Ursula McTaggart Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy In the Departments of English and American Studies Indiana University June 2008 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Doctoral Committee ________________________________ Purnima Bose, Co-Chairperson ________________________________ Margo Crawford, Co-Chairperson ________________________________ DeWitt Kilgore ________________________________ Robert Terrill June 18, 2008 ii © 2008 Ursula McTaggart ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A host of people have helped make this dissertation possible. My primary thanks go to Purnima Bose and Margo Crawford, who directed the project, offering constant support and invaluable advice. They have been mentors as well as friends throughout this process. Margo’s enthusiasm and brilliant ideas have buoyed my excitement and confidence about the project, while Purnima’s detailed, pragmatic advice has kept it historically grounded, well documented, and on time! Readers De Witt Kilgore and Robert Terrill also provided insight and commentary that have helped shape the final product. In addition, Purnima Bose’s dissertation group of fellow graduate students Anne Delgado, Chia-Li Kao, Laila Amine, and Karen Dillon has stimulated and refined my thinking along the way. Anne, Chia-Li, Laila, and Karen have devoted their own valuable time to reading drafts and making comments even in the midst of their own dissertation work. This dissertation has also been dependent on the activist work of the Black Panther Party, the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, the International Socialists, the Socialist Workers Party, and the diverse field of contemporary anarchists. -

Picking up the Books: the New Historiography of the Black Panther Party

PICKING UP THE BOOKS: THE NEW HISTORIOGRAPHY OF THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY David J. Garrow Paul Alkebulan. Survival Pending Revolution: The History of the Black Panther Party. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2007. 176 pp. Notes, bibliog- raphy, and index. $28.95. Curtis J. Austin. Up Against the Wall: Violence in the Making and Unmaking of the Black Panther Party. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2006. 456 pp. Photographs, notes, bibliography, and index. $34.95. Paul Bass and Douglas W. Rae. Murder in the Model City: The Black Panthers, Yale, and the Redemption of a Killer. New York: Basic Books, 2006. 322 pp. Pho- tographs, notes, bibliography, and index. $26.00. Flores A. Forbes. Will You Die With Me? My Life and the Black Panther Party. New York: Atria Books, 2006. 302 pp. Photographs and index. $26.00. Jama Lazerow and Yohuru Williams, eds. In Search of the Black Panther Party: New Perspectives on a Revolutionary Movement. Durham: Duke University Press, 2006. 390 pp. Notes and index. $84.95 (cloth); $23.95 (paper). Jane Rhodes. Framing the Black Panthers: The Spectacular Rise of a Black Power Icon. New York: The New Press, 2007. 416 pp. Notes, bibliography, and index. $35.00. A comprehensive review of all published scholarship on the Black Panther Party (BPP) leads to the inescapable conclusion that the huge recent upsurge in historical writing about the Panthers begins from a surprisingly weak and modest foundation. More than a decade ago, two major BPP autobiographies, Elaine Brown’s A Taste of Power (1992) and David Hilliard’s This Side of Glory (1993), along with Hugh Pearson’s widely reviewed book on the late BPP co-founder Huey P. -

Modernism and Christian Socialism in the Thought of Ottokã¡R Prohã¡Szka

Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe Volume 12 Issue 3 Article 6 6-1992 Modernism and Christian Socialism in the Thought of Ottokár Prohászka Leslie A. Muray Lansing Community College, Michigan Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ree Part of the Christianity Commons, and the Eastern European Studies Commons Recommended Citation Muray, Leslie A. (1992) "Modernism and Christian Socialism in the Thought of Ottokár Prohászka," Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe: Vol. 12 : Iss. 3 , Article 6. Available at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ree/vol12/iss3/6 This Article, Exploration, or Report is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I ; MODERNISM AND CHRISTIAN SOCIALISM IN THE THOUGHT OF OTTOKAR PROHASZKA By Leslie A. Moray Dr. Leslie A. Muray (Episcopalian) is professor of religious studies at the Lansing Community College in Lansing, Michigan. He obtained his Ph.D. degree from the Graduate Theological School in Claremont, California. Several of his previous articles were published in OPREE. Little known in the West is the life and work of the Hungarian Ottokar Prohaszka (1858- 1927), Roman Catholic Bishop of Szekesfehervar and a university professor who was immensely popular and influential in Hungary at the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth centuries. He was the symbol of modernism, for which three of his works were condemned, and Christian Socialism in his native land. -

The Politics of Anarchy in Anarcho Punk,1977-1985

No Compromise with Their Society: The Politics of Anarchy in Anarcho Punk,1977-1985 Laura Dymock Faculty of Music, Department of Music Research, McGill University, Montréal September, 2007 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts, Musicology © Laura Dymock, 2007 Libraryand Bibliothèque et 1+1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l'édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-38448-0 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-38448-0 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l'Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, électronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriété du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Mark Gerard Mantho

Mark G. Mantho Radical Chic © Readers are apt to remember Tom Wolfe’s books – The Electric Cool-Aid Acid Test, The Right Stuff, Bonfire of the Vanities, and all the rest – as much for their style as their subject matter. And while his subject matter tends to age poorly, Radical Chic reminds that Wolfe’s style – loquacious, informal, freakishly extravagant – still inspires admiration. In Radical Chic, Wolfe’s account of the infamous “Panther Party” thrown by Leonard Bernstein and its unhappy consequences for the aggrieved conductor and his wife, the author’s stylistic tricks are readily apparent. Wolfe begins by writing as if he himself were a charter member of mid-60s New York Society. He drops names (“”Jason Robards, John and D.D. Ryan, Gian-Carlo Menotti, Schuyler Chapin, Goddard Lieberson, Mike Nichols, Lillian Hellman, Larry Rivers, Aaron Copland, Richard Avedon, Milton and Amy Greene, Lukas Foss, Jennie Tourel, Samuel Barber, Jerome Robbins, Steve Sondheim, Adolph and Phyllis Green, Betty Comden, and the Patrick O’Neils…”). He slips in a bit of fashionable French (en passant, politesse, nostalgie de la boue), but not too much; that would be gauche. He proclaims, as only an elitist East Side aesthete can, the absolute psychological necessity of the servant class (“…with the morning workout on the velvet swings at Kounovsky’s and the late mornings on the telephone, and lunch at the Running Footman, which is now regarded as really better than La Grenouille, Lutece, Lafayette, La Caravelle, and the rest of the general Frog Pond, less ostentatious, more of the David Hicks feeling, less of the Parish-Hadley look, and then – well, then, the idea of not having servants is unthinkable. -

A Plea for Leninist Intolerance Slavoj Žižek Critical Inquiry, Vol. 28, No. 2. (Winter, 2002), Pp. 542-566

A Plea for Leninist Intolerance Slavoj Žižek Critical Inquiry, Vol. 28, No. 2. (Winter, 2002), pp. 542-566. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0093-1896%28200224%2928%3A2%3C542%3AAPFLI%3E2.0.CO%3B2-Q Critical Inquiry is currently published by The University of Chicago Press. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/ucpress.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers, and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community take advantage of advances in technology. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org Tue Mar 25 13:29:57 2008 A Plea for Leninist Intolerance Slavoj ~iiek LeninS Choice What is tolerance today? The most popular TV show of the fall of 2000 in France, with a viewer rating two times higher than that of the notori- ous Big Brother reality soap, is C'est mon choix (It's my choice) on France 3, a talk-show whose guest is each time an ordinary (or, exceptionally, well- known) person who made a peculiar choice that determined his or her entire lifestyle. -

Public Communication in Totalitarian, Authoritarian and Statist Regimes: a Comparative Glance 2010

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Jean K. Chalaby Public Communication in Totalitarian, Authoritarian and Statist Regimes: A Comparative Glance 2010 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/12402 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Sammelbandbeitrag / collection article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Chalaby, Jean K.: Public Communication in Totalitarian, Authoritarian and Statist Regimes: A Comparative Glance. In: Kirill Postoutenko (Hg.): Totalitarian Communication – Hierarchies, Codes and Messages. Bielefeld: transcript 2010, S. 67–89. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/12402. Erstmalig hier erschienen / Initial publication here: https://doi.org/10.14361/transcript.9783839413937.67 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons - This document is made available under a creative commons - Namensnennung - Nicht kommerziell - Keine Bearbeitungen 4.0 Attribution - Non Commercial - No Derivatives 4.0 License. For Lizenz zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz more information see: finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 Public Communication in Totalitarian, Authoritarian and Statist Regimes A Comparative Glance1 JEAN K. CHALABY Introduction This article addresses the following issue: how distinctive was the polit- ical communication system that prevailed during the de Gaulle presi- dency? How democratic was it? To this end, this essay places the French political communication system in a comparative perspective and con- structs a typology that contrasts different models, placing the emphasis on the ideology and elite mindset that underpin them. These types comprise totalitarianism, authoritarianism, statism and liberalism. This article makes two main arguments. Regarding France, it shows that statism, particularly since the de Gaulle presidency, has had a lasting influence on the country’s communication system. -

We Speak a Different Tongue

We Speak a Different Tongue We Speak a Different Tongue: Maverick Voices and Modernity 1890–1939 Edited by Anthony Patterson and Yoonjoung Choi We Speak a Different Tongue: Maverick Voices and Modernity 1890–1939 Edited by Anthony Patterson and Yoonjoung Choi This book first published 2015 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2015 by Anthony Patterson, Yoonjoung Choi and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-7702-6 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-7702-2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements .................................................................................. viii Introduction ............................................................................................... ix Anthony Patterson and Yoonjoung Choi Part I: Contexts Chapter One ................................................................................................. 2 “Destroying Natural Ties”: Radical Politics at the Margins of Modernism Cord-Christian Casper Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 21 Literary Modernism and Philosophical Pragmatism: Convergence and Difference -

Thearchive.Pdf

The Archive Issue No.2 May 2013 FOREWORD: In February, Michael Gove, Secretary of State for Education, announced his proposals for the new history curriculum, only to spark huge controversy. Academic historians have condemned it as ‘history for football hooligans’, whilst its supporters point to the current curriculum’s neglecting of essential facts and chronology. Gove’s history syllabus for children up to the age of fourteen is essentially ‘Our Island’s story’, told in sequence with facts and dates. Various criticisms have arisen from this focus on ‘Our Island’s Story’, primarily the concern that the emphasis solely on British history ‘will produce a generation of young Britons with no knowledge of the history of any part of the world beyond the shores of the British Isles’. 1 Moreover, sequential teaching of history is seen to ‘rip events out of their context, leaving them insusceptible to analysis’.2 This concern with analysis picks out a key purpose of teaching history, and is something that Richard Evans puts much focus on: he appears to see history as a vehicle for teaching analytical skills that can then be applied to everyday life. Yet history is debatably more than just a ‘vehicle for teaching analytical skills’. History is valuable in and of itself and thus whilst both sides of the debate have merit, what is perhaps more interesting is the question it should make us ask about what is the purpose of studying and teaching history. As is the nature of history, there is also no clear answer to this question. Nonetheless, whether the purpose of teaching history is the instilling of national values and the creation of a national identity, or whether it is the means of equipping students with a framework for interpreting the world in which we live, it is apparent from the current debates that history is rightly perceived as something that is extremely valuable, powerful, and arguably even dangerous.