Judicial Opinion Writing: Gerald Lebovits

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table of Contents

T a b l e C o n T e n T s I s s u e 9 s u mm e r 2 0 1 3 o f pg 4 pg 18 pg 26 pg 43 Featured articles Pg 4 abraham lincoln and Freedom of the Press A Reappraisal by Harold Holzer Pg 18 interbranch tangling Separating Our Constitutional Powers by Judith s. Kaye Pg 26 rutgers v. Waddington Alexander Hamilton and the Birth Pangs of Judicial Review by David a. Weinstein Pg 43 People v. sanger and the Birth of Family Planning clinics in america by Maria T. Vullo dePartments Pg 2 From the executive director Pg 58 the david a. Garfinkel essay contest Pg 59 a look Back...and Forward Pg 66 society Officers and trustees Pg 66 society membership Pg 70 Become a member Back inside cover Hon. theodore t. Jones, Jr. In Memoriam Judicial Notice l 1 From the executive director udicial Notice is moving forward! We have a newly expanded board of editors Dearwho volunteer Members their time to solicit and review submissions, work with authors, and develop topics of legal history to explore. The board of editors is composed J of Henry M. Greenberg, Editor-in-Chief, John D. Gordan, III, albert M. rosenblatt, and David a. Weinstein. We are also fortunate to have David l. Goodwin, Assistant Editor, who edits the articles and footnotes with great care and knowledge. our own Michael W. benowitz, my able assistant, coordinates the layout and, most importantly, searches far and wide to find interesting and often little-known images that greatly compliment and enhance the articles. -

Rehabilitating Child Welfare: Children and Public Policy, 1945-1980

Rehabilitating Child Welfare: Children and Public Policy, 1945-1980 Ethan G. Sribnick Silver Spring, Maryland B.A., University of Chicago, 1998 M.A., University of Virginia, 2001 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Virginia May2007 © Copyright by Ethan G. Sribnick All Rights Reserved May 2007 111 Abstract In the period afterWorld War II, a network of activists attempted to reformthe programs that supported and assisted delinquent, dependent, neglected, abused and abandoned children and their familiesin the United States. This dissertation examines their effortsto reshape child welfare arguing that it was motivated by the "rehabilitative ideal," a belief that the state was ultimately responsible forthe physical and emotional development of every child and a faithin therapeutic services as a way of providing for children and their families. This argument contributes to our understanding of the rise of a therapeutic state, placing this notion within a particular historical period and within the narrative of the changing nature of American liberalism. The rehabilitative ideal and the child welfare network emerged out of a confluence of trends within American liberalism, social welfare agencies, and social work approaches in the period after 1945. This study provides detailed examination of this phenomenon through the lives of Justine Wise Polier, Joseph H. Reid, and Alfred J. Kahn, and the histories of the Citizens' Committee forChildren of New York, the Child Welfare League of America, and the Columbia University School of Social Work. Investigations of the developments in juvenile justice, fostercare and adoption, child protection, and federalassistance to child welfareservices over the 1950s and 1960s demonstrate how the rehabilitative approach shaped child welfare reform. -

In the United States District Court

Case 1:13-cv-06802-WHP Document 567 Filed 05/02/16 Page 1 of 17 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK THE DIAL CORPORATION, et al., Civil Action No. 13-cv-06802-WHP Individually and on behalf of Similarly Situated Companies, Plaintiffs, v. NEWS CORPORATION, et al., Defendants. DECLARATION OF STEVEN F. BENZ IN SUPPORT OF MOTION FOR PRELIMINARY APPROVAL OF SETTLEMENT Case 1:13-cv-06802-WHP Document 567 Filed 05/02/16 Page 2 of 17 I, Steven F. Benz, declare as follows: 1. I submit this declaration in support of preliminary approval of the settlement reached on behalf of the certified Class and Defendants News Corporation, News America, Inc., News America Marketing In-Store Services L.L.C., and News America Marketing FSI L.L.C. (collectively, “Defendants”). 2. I am a partner with the law firm of Kellogg, Huber, Hansen, Todd, Evans & Figel, P.L.L.C. (“Kellogg Huber”), which is Co-Lead Counsel for the Class of plaintiffs certified by the Court on June 18, 2015. I am a member of good standing of the District of Columbia, Iowa, Maryland and Minnesota bars, and am admitted to practice before this Court pro hac vice. I have personal knowledge of the matters set forth in this declaration. I became involved in this case at its inception in 2011 and am closely familiar with all aspects of this case since that time. 3. Both Kellogg Huber and I personally have significant experience with antitrust litigation and class actions, including settlements thereof. Copies of my firm’s resume and my personal profile are annexed to this declaration as Exhibit A. -

Honoring Our Own the WWII Veteran Judges of the Eastern District of New York

Honoring Our Own The WWII Veteran Judges of the Eastern District of New York On Dec. 5, 2012, the Eastern District of New York Chapter of the Federal Bar Association held a program at the American Airpower Museum to honor the district’s distinguished World War II veteran judges. It has often been said that the World War II brothers-in-arms are members of the “greatest generation.” Assuredly, it is not an overstatement to say that our World War II veteran judges and their brothers-in-arms walk among the greatest men of any generation. Each of the honorees are briefly biographied in the pages that fol- low, describing how service to our country has affected their lives and careers. Hon. I. Leo Glasser Born in New York City in 1924, Judge Glasser graduated from the City College of New York in 1943 and then served in the U.S. Army in Europe during World War II. During the war, Judge Glasser served as a U.S. Army infantry technician landing in Europe a few weeks after D-Day at the small French town of St. Mere Eglise. His unit pushed east, eventu- ally crossing into Germany in Spring 1945. The horror of battle was constant. Judge Glasser was wounded while moving ammunition crates and was awarded the Bronze Star for bravery during his service in the European theater. In an article published by Newsday, May 27, 2012, Judge Glasser was quoted as saying: “I hope there will come a day when we have no more war and the lion will lie down with the lamb and we can have universal peace.” Upon returning from the war, Judge Glasser obtained a law degree magna cum laude from Brooklyn Law School in 1948, and then immediately began teaching at Brooklyn Law School. -

Signed Opinions, Concurrences, Dissents, and Vote Counts in the U.S

Akron Law Review Volume 53 Issue 3 Federal Appellate Issue Article 2 2019 Signed Opinions, Concurrences, Dissents, and Vote Counts in the U.S. Supreme Court: Boon or Bane? (A Response to Professors Penrose and Sherry) Joan Steinman Follow this and additional works at: https://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/akronlawreview Part of the Courts Commons, Judges Commons, and the Litigation Commons Please take a moment to share how this work helps you through this survey. Your feedback will be important as we plan further development of our repository. Recommended Citation Steinman, Joan (2019) "Signed Opinions, Concurrences, Dissents, and Vote Counts in the U.S. Supreme Court: Boon or Bane? (A Response to Professors Penrose and Sherry)," Akron Law Review: Vol. 53 : Iss. 3 , Article 2. Available at: https://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/akronlawreview/vol53/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Akron Law Journals at IdeaExchange@UAkron, the institutional repository of The University of Akron in Akron, Ohio, USA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Akron Law Review by an authorized administrator of IdeaExchange@UAkron. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Steinman: Response to Penrose and Sherry SIGNED OPINIONS, CONCURRENCES, DISSENTS, AND VOTE COUNTS IN THE U.S. SUPREME COURT: BOON OR BANE? (A RESPONSE TO PROFESSORS PENROSE AND SHERRY) Joan Steinman* I. Response to Professor Penrose .................................. 526 II. Response to Professor Sherry .................................... 543 A. A Summary of Professor Sherry’s Arguments, and Preliminary Responses ........................................ 543 B. Rejoinders to Professor Sherry’s Arguments ...... 548 1. With Respect to the First Amendment ......... -

A Tribute to the Fordham Judiciary: a Century of Service

Fordham Law Review Volume 75 Issue 5 Article 1 2007 A Tribute to the Fordham Judiciary: A Century of Service Constantine N. Katsoris Fordham University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Constantine N. Katsoris, A Tribute to the Fordham Judiciary: A Century of Service, 75 Fordham L. Rev. 2303 (2007). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol75/iss5/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Law Review by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Tribute to the Fordham Judiciary: A Century of Service Cover Page Footnote * This article is dedicated to Justice Sandra Day O'Connor, the first woman appointed ot the U.S. Supreme Court. Although she is not a graduate of our school, she received an honorary Doctor of Laws degree from Fordham University in 1984 at the dedication ceremony celebrating the expansion of the Law School at Lincoln Center. Besides being a role model both on and off the bench, she has graciously participated and contributed to Fordham Law School in so many ways over the past three decades, including being the principal speaker at both the dedication of our new building in 1984, and again at our Millennium Celebration at Lincoln Center as we ushered in the twenty-first century, teaching a course in International Law and Relations as part of our summer program in Ireland, and participating in each of our annual alumni Supreme Court Admission Ceremonies since they began in 1986. -

Extensions of Remarks E356 HON. ALAN S. LOWENTHAL HON

E356 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks March 21, 2017 NATIONAL ROSIE THE RIVETER IN HONOR OF ALABAMA STATE I honor all of the work Kitty accomplished in DAY: A TRIBUTE TO THE LONG UNIVERSITY’S WAR GARDENS our community and the trail she blazed for the BEACH ROSIE THE RIVETER women inspired by her achievements. PARK HON. MARTHA ROBY f OF ALABAMA PERSONAL EXPLANATION HON. ALAN S. LOWENTHAL IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Tuesday, March 21, 2017 HON. LUIS V. GUTIE´RREZ OF CALIFORNIA Mrs. ROBY. Mr. Speaker, I rise today to OF ILLINOIS IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES honor Alabama State University upon its 100 IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES year anniversary of planting war gardens to Tuesday, March 21, 2017 Tuesday, March 21, 2017 aid the United States efforts in World War I. Mr. GUTIE´ RREZ. Mr. Speaker, I was un- Mr. LOWENTHAL. Mr. Speaker, I am a One hundred years ago, students, staff, and avoidably absent in the House chamber for roll proud co-sponsor of House Resolution 162, faculty of the then State Normal School at call votes 173, 174, 175 on Monday, March which will designate March 21, 2017, as Na- Montgomery, subsequently Alabama State 20, 2017. Had I been present, I would have tional Rosie the Riveter Day. This honor has University, assisted and advised residents voted ‘‘Yea’’ on roll call votes 173, 174, and special significance for the City of Long near campus and in the City of Montgomery, 175. Beach, California which I represent. Alabama on how to plant war gardens. Thanks f to these efforts, it was reported that in March Long Beach is one of two locations in the 1918 over 1,400 black homes in Montgomery SPECIAL TRIBUTE IN HONOR OF nation that has a park dedicated to recog- had war gardens. -

New York Family Court: Court User Perspectives

New York Family Court Court User Perspectives Julia Vitullo-Martin Brian Maxey January 2000 12 This project was supported by a grant administered by the New York Community Trust. Points of view in this document are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the New York Community Trust. Preface New Yorkers demand a lot from the city’s Family Court. First established 37 years ago as an experimental court to oversee all family problems in one location, Family Court has jurisdiction over the immensely complex issues of custody and visitation, paternity, family violence, child support, abuse and neglect, foster care, and most delinquency matters. Today Family Court’s caseload is high, its physical plant deteriorating, and its resources strained. The court is looking both within and without for analysis of current problems and directions for the future. This report, funded by the New York Community Trust and prepared by the Vera Institute, is one step in the court's analysis. It examines the data from the first-ever systematic survey of Family Court users: both professional users (such as lawyers and caseworkers) and nonprofessional users (family members, teachers, and neighbors of the children and adults who depend on the court). The findings are straightforward, encompassing both unanticipated praise in some areas and distress in others. Most civilian users have something good to say about Family Court—particularly about the court officers, who are often credited with being the best part of the system. Yet the problems are many, ranging from difficulties navigating the court physically to the burdens of the court’s rigid calendar. -

Statutory Interpretation--In the Classroom and in the Courtroom

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 1983 Statutory Interpretation--in the Classroom and in the Courtroom Richard A. Posner Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/journal_articles Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Richard A. Posner, "Statutory Interpretation--in the Classroom and in the Courtroom," 50 University of Chicago Law Review 800 (1983). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Statutory Interpretation-in the Classroom and in the Courtroom Richard A. Posnerf This paper continues a discussion begun in an earlier paper in this journal.1 That paper dealt primarily with the implications for statutory interpretation of the interest-group theory of legislation, recently revivified by economists; it also dealt with constitutional interpretation. This paper focuses on two topics omitted in the earlier one: the need for better instruction in legislation in the law schools and the vacuity of the standard guideposts to reading stat- utes-the "canons of construction." The topics turn out to be re- lated. The last part of the paper contains a positive proposal on how to interpret statutes. I. THE ACADEMIC STUDY OF LEGISLATION It has been almost fifty years since James Landis complained that academic lawyers did not study legislation in a scientific (i.e., rigorous, systematic) spirit,' and the situation is unchanged. There are countless studies, many of high distinction, of particular stat- utes, but they are not guided by any overall theory of legislation, and most academic lawyers, like most judges and practicing law- yers, would consider it otiose, impractical, and pretentious to try to develop one. -

Impersonal Names Index Listing for the INSCOM Investigative Records Repository, 2010

Description of document: US Army Intelligence and Security Command (INSCOM) Impersonal Names Index Listing for the INSCOM Investigative Records Repository, 2010 Requested date: 07-August-2010 Released date: 15-August-2010 Posted date: 23-August-2010 Title of document Impersonal Names Index Listing Source of document: Commander U.S. Army Intelligence & Security Command Freedom of Information/Privacy Office ATTN: IAMG-C-FOI 4552 Pike Road Fort George G. Meade, MD 20755-5995 Fax: (301) 677-2956 Note: The IMPERSONAL NAMES index represents INSCOM investigative files that are not titled with the name of a person. Each item in the IMPERSONAL NAMES index represents a file in the INSCOM Investigative Records Repository. You can ask for a copy of the file by contacting INSCOM. The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. -

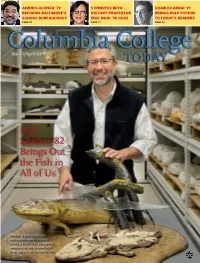

Neil Shubin '82 Brings out the Fish in All of Us

ANDRES ALONSO ’79 5 MINUTES WITH … CHARLES ARDAI ’91 REFORMS BALTIMORE’S HISTORY PROFESSOR BRINGS PULP FICTION SCHOOL BUREAUCRACY MAE NGAI ’98 GSAS TO TODAY’S READERS PAGE 22 PAGE 11 PAGE 24 Columbia College March/April 2011 TODAY Neil Shubin ’82 Brings Out the Fish in All of Us Shubin, a paleontologist and evolutionary biologist, co-led a team that discovered evidence of the pivotal shift from aquatic to terrestrial life. ust another J membership perk. Meet. Dine. Entertain. Join the Columbia Club and access state-of-the-art meeting rooms for your conferences and events. For more information or to apply, visit www.columbiaclub.org or call (212) 719-0380. The Columbia University Club of New York in residence at 15 West 43 St. New York, N Y 10036 Columbia’s SocialIntellectualCulturalRecreationalProfessional Resource in Midtown. Columbia College Today Contents 22 12 24 7 56 18 COVER STORY ALUMNI NEWS DEPARTMENTS G O FISH 27 O BITUARIES 2 LETTERS TO THE 12 Paleontologist and evolutionary biologist Neil Shubin 27 Joseph D. Coffee Jr. ’41 EDITOR ’82 brings out the fish in all of us. 28 Garland E. Wood ’65 3 ITHIN THE AMILY By Nathalie Alonso ’08 W F 30 B OOKSHEL F 4 AROUND THE QUADS FEATURES Featured: Adam Gidwitz ’04 4 turns classic folklore on its Northwest Corner Building Opens COLUMBIA FORUM ear with his new children’s 18 book, A Tale Dark & Grimm. 5 Rose, Jones Join In an excerpt from his book How Soccer Explains the College Senior Staff World: An Unlikely Theory of Globalization, Franklin 32 LASS OTES 6 Creed To Deliver Foer ’96 explains how one soccer club’s destiny was C N A LUMNI PRO F ILES Class Day Address shaped by European anti-Semitism. -

Anna Moscowitz Kross and the Home Term Part: a Second Look at the Nation’S First Criminal Domestic Violence Court

The University of Akron IdeaExchange@UAkron Akron Law Review Akron Law Journals June 2015 Anna Moscowitz Kross and The omeH Term Part: A Second Look at the Nation's First Criminal Domestic Violence Court Mae C. Quinn Please take a moment to share how this work helps you through this survey. Your feedback will be important as we plan further development of our repository. Follow this and additional works at: http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/akronlawreview Part of the Family Law Commons, and the Law and Gender Commons Recommended Citation Quinn, Mae C. (2008) "Anna Moscowitz Kross and The omeH Term Part: A Second Look at the Nation's First Criminal Domestic Violence Court," Akron Law Review: Vol. 41 : Iss. 3 , Article 3. Available at: http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/akronlawreview/vol41/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Akron Law Journals at IdeaExchange@UAkron, the institutional repository of The nivU ersity of Akron in Akron, Ohio, USA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Akron Law Review by an authorized administrator of IdeaExchange@UAkron. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Quinn: A Second Look at the Nation's First Domestic Violence Court QUINN_FINAL 3/23/2009 3:03 PM ANNA MOSCOWITZ KROSS AND THE HOME TERM PART: A SECOND LOOK AT THE NATION’S FIRST CRIMINAL DOMESTIC VIOLENCE COURT Mae C. Quinn∗ I. Introduction ....................................................................... 733 II. Kross’s Early Women’s Rights Work ............................... 737 III. Kross’s Court Reform and Judicial Innovation Efforts ..... 739 IV. Kross’s Home Term Part: The Nation’s First Criminal Domestic Violence Court .................................................