Eritrea-Ethiopia Claims Commission - Partial Award: Prisoners of War - Eritrea's Claim 17

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Situation Report EEPA HORN No. 59 - 18 January 2021

Situation Report EEPA HORN No. 59 - 18 January 2021 Europe External Programme with Africa is a Belgium-based Centre of Expertise with in-depth knowledge, publications, and networks, specialised in issues of peace building, refugee protection and resilience in the Horn of Africa. EEPA has published extensively on issues related to movement and/or human trafficking of refugees in the Horn of Africa and on the Central Mediterranean Route. It cooperates with a wide network of Universities, research organisations, civil society and experts from Ethiopia, Eritrea, Kenya, Djibouti, Somalia, Sudan, South Sudan, Uganda and across Africa. Reported war situation (as confirmed per 17 January) - According to Sudan Tribune, the head of the Sudanese Sovereign Council, Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, disclosed that Sudanese troops were deployed on the border as per an agreement with the Ethiopian Prime Minister, Abiy Ahmed, arranged prior to the beginning of the war. - Al-Burhan told a gathering about the arrangements that were made in the planning of the military actions: “I visited Ethiopia shortly before the events, and we agreed with the Prime Minister of Ethiopia that the Sudanese armed forces would close the Sudanese borders to prevent border infiltration to and from Sudan by an armed party.” - Al-Burhan stated: "Actually, this is what the (Sudanese) armed forces have done to secure the international borders and have stopped there." His statement suggests that Abiy Ahmed spoke with him about the military plans before launching the military operation in Tigray. - Ethiopia has called the operation a “domestic law and order” action to respond to domestic provocations, but the planning with neighbours in the region on the actions paint a different picture. -

Ethiopia Country Office Humanitarian Situation Report Includes Results from Tigray Response

Ethiopia Country Office Humanitarian Situation Report Includes results from Tigray Response © UNICEF Ethiopia/2021/Nahom Tesfaye Situation in Numbers Reporting Period: May 2021 12.5 million Highlights children in need of humanitarian assistance (HNO 2021) In May, 56,354 new medical consultations were conducted in Afar, Somali and Tigray regions through the 79 UNICEF- supported Mobile Health and Nutrition Teams (MHNTs), 23.5 million 11,692 of these in Tigray through the 30 active MHNTs. people in need UNICEF reached 412,647 people in May and 2,881,630 (HNO 2021) people between January to May 2021 throughout Ethiopia with safe water for drinking, cooking, and personal hygiene 2 through the rehabilitation of non-functional water systems, 3.6 million water treatment, and water trucking; of these, 1,228,921 were internally displaced people (DTM, in Tigray 2021) Since the beginning of the Tigray crisis, UNICEF has delivered 2,352 metric tons of multi-sectoral supplies to nine 806,541 partners (including Regional Bureaus) working in the region, valued at US$ 4.6 million. registered refugees (UNHCR,31 May 2021) In May, UNICEF supported the treatment of 38,032 under 5 children with Severe Acutely Malnutrition (SAM) in Ethiopia (1,723 in Tigray); 40.6 per cent of these were in Oromia, 20.7 per cent in Somali, 15.4 percent in SNNP/Sidama, 12.7 percent in Amhara and 4.5 per cent in Tigray. A total of UNICEF Revised HAC Appeal 152,413 children in the country have been treated for SAM between January – April 2021 with UNICEF direct support 2021 -

Situation Report Last Updated: 19 Aug 2021

ETHIOPIA - TIGRAY REGION HUMANITARIAN UPDATE Situation Report Last updated: 19 Aug 2021 HIGHLIGHTS (19 Aug 2021) Humanitarian access into Tigray remains restricted to one road through Afar Region, with insecurity, extended delays with clearances, and intense search at checkpoints. One hundred trucks of food, non-food items and fuel, including at least 90 trucks of food, must enter Tigray every day to sustain assistance for at least 5.2 million people. Between 5-11 August, food partners reached more than 320,000 people under Round 1 and more than 1 million people under Round 2. Partners reached about 184,000 people with water, 10,000 children with educational programs, and The boundaries and names shown and the designations donated 10,000 textbooks in support of the school used on this map do not imply official endorsement or reopening effort. acceptance by the United Nations. © OCHA The spill over of the conflict into neighbouring Afar and Amhara regions continues to take a heavy toll on civilians. KEY FIGURES FUNDING CONTACTS Hayat Abu Saleh 5.2M 5.2M $854M $170.7M Public Information Officer People in need People targeted Requirements (May - Outstanding gap (Aug [email protected] December) - Dec) Saviano Abreu 63,110 Public Information Officer Refugees in Sudan [email protected] since 7 November BACKGROUND (19 Aug 2021) Disclaimer OCHA Ethiopia prepares this report with the support of Cluster Coordinators. The data/information collected covers the period from 10- 16 August. The dashboard data below is as of 13 August. In some cases, access and communication constraints mean that updates for the period are delayed. -

20210502 Operating MHNT in Tigray-Week 17 Copy

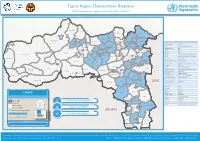

Tigray Region Humanitarian Response MHNT operating in Tigray as of 02 May 2021 - Week 17 Adi Hageray Seyemti Adyabo Zala Anbesa town Egela Erob Gulo Mekeda Sheraro town Ahsea Rama Tahtay Adiyabo Adi Daero Chila Aheferom Saesie Woreda Partners Enticho town Bizet Adigrat town Selekleka Abi Adi town AAH Setit Humera Laelay Adiabo Adwa Ganta Afeshum Edaga Hamus town Adet MSF-S/TRHB/UNICEF Tahtay Koraro Adwa town Hahayle Adigrat town SCI Axum town Indasilassie town Tsaeda Emba Tahtay Mayechew Adwa SCI Asgede Laelay Maychew Emba Sieneti Freweyni town Ahsea MSF-S Kafta Humera Atsbi TRHB/UNICEF/USAID-TPHC Naeder Hawzen town Atsbi Endafelasi Edaga arbi Bizet TRHB/UNICEF/USAID-TPHC Endabaguna town Hawzen May Kadra Zana Kelete Awelallo Bora (TG) TRHB/MSI Korarit Atsbi town Tsimbla Edaga Hamus town TRHB/UNICEF Adet Emba Alaje TRHB/UNICEF/USAID-TPHC May Gaba Wukro town Geraleta Enderta GEI/GEI Keyhe tekli Erob MSF-S/TRHB/MSI Agulae Welkait Dima (TG) Freweyni town TRHB/UNICEF/USAID-TPHC Awra (TG) Kola Temben Hagere Selam town Tselemti Abi Adi town Ganta Afeshum MSF-S/SCI Degua Temben May Tsebri town Tanqua Melashe Geraleta TRHB/UNICEF Dansha town Mekelle Gulo Mekeda MSF-S/SCI/TRHB/MSI Indasilassie town IOM/MCMDO Tsegede (TG) Kelete Awelallo GEI Abergele (TG) Saharti AFAR Laelay Adiabo MCMDO Enderta Laelay Maychew SCI Mekelle IOM Adigudom Naeder MSF-S Ofla MCMDO LEGEND Samre Hintalo Rama MSF-S Raya Azebo MCMDO Wajirat Saesie CWW/GEI/MSF-S Selewa Sahar� MCMDO Emba Alaje Admin 1 / Region 11 Partners Operating MHNTs Samre CWW Admin 2 / Zone Bora (TG) Tahtay -

Starving Tigray

Starving Tigray How Armed Conflict and Mass Atrocities Have Destroyed an Ethiopian Region’s Economy and Food System and Are Threatening Famine Foreword by Helen Clark April 6, 2021 ABOUT The World Peace Foundation, an operating foundation affiliated solely with the Fletcher School at Tufts University, aims to provide intellectual leadership on issues of peace, justice and security. We believe that innovative research and teaching are critical to the challenges of making peace around the world, and should go hand-in- hand with advocacy and practical engagement with the toughest issues. To respond to organized violence today, we not only need new instruments and tools—we need a new vision of peace. Our challenge is to reinvent peace. This report has benefited from the research, analysis and review of a number of individuals, most of whom preferred to remain anonymous. For that reason, we are attributing authorship solely to the World Peace Foundation. World Peace Foundation at the Fletcher School Tufts University 169 Holland Street, Suite 209 Somerville, MA 02144 ph: (617) 627-2255 worldpeacefoundation.org © 2021 by the World Peace Foundation. All rights reserved. Cover photo: A Tigrayan child at the refugee registration center near Kassala, Sudan Starving Tigray | I FOREWORD The calamitous humanitarian dimensions of the conflict in Tigray are becoming painfully clear. The international community must respond quickly and effectively now to save many hundreds of thou- sands of lives. The human tragedy which has unfolded in Tigray is a man-made disaster. Reports of mass atrocities there are heart breaking, as are those of starvation crimes. -

(RMOS) for Irrigated High Value Crops (Ihvc) in Tigray Region, Northern Ethiopia

Regional Market Opportunity Study (RMOS) for Irrigated High Value Crops (iHVC) in Tigray Region, Northern Ethiopia Mekele, Ethiopia July, 2019 Participatory Small-Scale Irrigation Development Program (PASIDP-II) Regional Market Opportunity Study (RMOS)for IrrigatedHigh Value Crops (iHVC) in 13Woredas of Tigray Region, Northern Ethiopia Prepared by the Bafana Business Management Consultant (BBBMC) and commissioned by Tigray Regional State Bureau of Agriculture and Rural Development (BoARD) and Financed by the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) through its project Participatory Small-Scale Irrigation Development Program (PASDIP). DISCLAIMER: The study is made possible by the support of the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD). The contents of this document are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of IFAD. i Acknowledgements The authors greatly acknowledge the contribution of everyone who participated in the study. Our heartfelt thanks go to the farming communities of the study area who provided their invaluable time, experience and knowledge through patiently answering our numerous questions. We also duly acknowledge the data collection team leader Haile Bayru Desta and several enumerators who were involved in gathering quality data. We owe special thanks to the Woreda Office Agriculture andRural Development (WoARD) for facilitating the access to secondary information, arranging household surveys and organizing focus group discussions (FGD). Tigray Agricultural Marketing Promotion Agency (TAMPA) provided access to secondary information including weekly price information of vegetables and fruits. The team would like to extend many thanks to Tigray Region State Bureau of Agriculture and Rural Development (BoARD) particularly the PASDIP team for facilitating the link with respective study Woredas and We thank Mr. -

Factors Affecting Choice of Place for Childbirth Among Women's in Ahferom Woreda, Tigray, 2013

Scholars Journal of Applied Medical Sciences (SJAMS) ISSN 2320-6691 (Online) Sch. J. App. Med. Sci., 2014; 2(2D):830-839 ISSN 2347-954X (Print) ©Scholars Academic and Scientific Publisher (An International Publisher for Academic and Scientific Resources) www.saspublisher.com Research Article Factors Affecting Choice of Place for Childbirth among Women’s in Ahferom Woreda, Tigray, 2013 Haftom Gebrehiwot Department of Midwifery, College of Health Sciences, Mekelle University, Ethiopia *Corresponding author Haftom Gebrehiwot Email: Abstract: Reduction of maternal mortality is a global priority. The key to reducing maternal mortality ratio is increasing attendance by skilled health personnel throughout pregnancy and delivery. However, delivery service is significantly lower in Tigray region. Therefore, this study aimed to assess factors affecting choice of place of child birth among women in Ahferom woreda. A community based cross-sectional study both quantitative and qualitative method was employed among 458 women of age 15-49 years that experienced child birth and pregnancy in Ahferom woreda, Ethiopia. Multi stage stratified sampling technique with Probabilities proportional to size was used to select the study subjects for quantitative and focus group discussions (FGDs) for the qualitative survey. Study subjects again were selected by systematic random sampling technique from randomly selected kebelle’s in the Woreda. Data was collected using structured interview questionnaire and analyzed using SPPS version 16.0. A total of 458 women participated in the quantitative survey. One third of women were age 35 and above, 118(25.8%) were aged between 25-29 years. 247(53.9%) of women were illiterate, and 58.7% of women choice home as place of birth and 41.3% choice health facilities. -

Agrarinvestitionen Und Tourismus

DEUTSCH-ÄTHIOPISCHER VEREIN E.V. ter t GERMAN ETHIOPIAN ASSOCIATION www.deutsch-aethiopischer-verein.de Ausgabe Juni 2015 Informationsblä Jahrestagung 2015: Situation behinderter Menschen und Naturmedizin befand sich in der Alpha School for the Deaf. Die Schule Gehörlose Kinder in Äthiopien hatte dieses in den achtziger Jahren als Geschenk aus Großbritannien erhalten. Selbst Fachärzte für HNO-Heil- Partnerschaft zwischen der Ludwig-Maximilians-Uni- kunde waren nicht im Besitz eines solchen. Hinzu kam, versität (LMU) München und der Universität Addis dass es kaum Fachärzte gab und wenn, arbeiteten sie Ababa zumeist in Addis Ababa. Der Lebensstandard war zwar auch hier niedrig, aber eben doch deutlich über dem des Annette Leonhardt, Lehrstuhl für Gehörlosen- und übrigen Landes. Eine erhebliche Anzahl der praktizieren- Schwerhörigenpädagogik, LMU München den Ärzte hatte ihre Ausbildung in den ehemaligen sozi- alistischen Ländern erhalten, vorzugsweise in der DDR, UdSSR, ČSFR (heute Tschechien und Slowakei), Polen Hintergrund der Zusammenarbeit und Bulgarien. Diese Möglichkeit der Ausbildung war Der erste Besuch Äthiopiens fand 1997 statt. Seither be- nun weggebrochen. Äthiopien war 1975 bis 1991 eben- stehen Arbeitskontakte zur Universität Addis Ababa. Zu- falls sozialistisch und erfuhr so die Hilfe dieser Länder. nächst wurde in den Jahren 2000 bis 2002 ein Projekt Das Bildungswesen Mitte/Ende der 90er Jahre war gemeinsam mit der Hilfsorganisation „Menschen für durch eine hohe Analphabetenrate gekennzeichnet. For- Menschen“ durchgeführt. Es diente der Unterstützung mal war die Schulpflicht gefordert, sie konnte aber durch einer konkreten Schule, nämlich der Alpha School for fehlende Lehrer, Schulen und Unterrichtsräume sowie the Deaf. Die Hilfsorganisation machte hier – um Kinder Unterrichtsmaterialien nicht durchgesetzt werden. -

Provenance of Sandstones in Ethiopia During

1 Provenance of sandstones in Ethiopia during Late 2 Ordovician and Carboniferous–Permian Gondwana 3 glaciations: petrography and geochemistry of the Enticho 4 Sandstone and the Edaga Arbi Glacials 5 6 Anna Lewina,*, Guido Meinholdb,c, Matthias Hinderera, Enkurie L. Dawitd, 7 Robert Busserte 8 9 aInstitut für Angewandte Geowissenschaften, Fachgebiet Angewandte 10 Sedimentologie, Technische Universität Darmstadt, Schnittspahnstraße 9, 11 64287 Darmstadt, Germany 12 bAbteilung Sedimentologie / Umweltgeologie, Geowissenschaftliches 13 Zentrum Göttingen, Universität Göttingen, Goldschmidtstraße 3, 37077 14 Göttingen, Germany 15 cSchool of Geography, Geology and the Environment, Keele University, 16 Keele, Staffordshire, ST5 5BG, UK 17 dDepartment of Geology, University of Gondar, P.O. Box 196, Gondar, 18 Ethiopia 19 eInstitut für Angewandte Geowissenschaften, Fachgebiet 20 Explorationsgeologie, Technische Universität Berlin, Ackerstraße 76, 13355 21 Berlin, Germany 22 23 *corresponding author. Tel. +49 6151 1620634 24 E-mail address: [email protected] (A. Lewin). 25 26 27 Abstract 28 29 We compare Ethiopian glaciogenic sandstone of the Late Ordovician 30 and Carboniferous–Permian Gondwana glaciations petrographically 31 and geochemically to provide insight into provenance, transport, and 32 weathering characteristics. Although several studies deal with the 33 glacial deposits in northern Africa and Arabia, the distribution of ice 34 sheets and continent-wide glacier dynamics during the two 35 glaciations remain unclear. Provenance data on Ethiopian Palaeozoic 36 sedimentary rocks are scarce. The sandstones of the Late Ordovician 37 glaciation are highly mature with an average quartz content of 95% 1 38 and an average chemical index of alteration of 85, pointing to intense 39 weathering and reworking prior to deposition. -

Hewn Churches and Its Surroundings, Tigray Region, Northern Ethiopia

Research Article http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/mejs.v9i2.4 Geological and Geomechanical Properties of Abraha-Atsibha and Wukro rock- hewn churches and its surroundings, Tigray Region, Northern Ethiopia Asmelash Abay*, Gebreslassie Mebrahtu and Bheemalingeswara Konka School of Earth Sciences, Mekelle University, P.O.Box:231, Mekelle, Ethiopia (*[email protected]). ABSTRACT Globally well-known ancient rock-hewn churches are present in Ethiopia in general and particularly in the central and eastern parts of Tigray regional state. They are important sites of heritage and tourism. Most of them are facing destabilization problem in different degree due to natural and anthropogenic factors. Among the affected, two churches hewn into sandstone located near Abreha-Atsibaha and Wukro (Kirkos/Cherkos church) in Tigray region were chosen for detailed study in terms of geological and engineering geological condition of the rocks in to which they are hewn. Both of them are affected by weathering and seepage. Both are carved into Mesozoic Adigrat sandstone that occupy higher elevations in topography, red in color and with iron and silica-rich alternating bands. Petrographic data suggest that the rock is dominated by quartz followed by feldspars; opaque and heavy minerals; pore spaces and carbonate/iron/silica cement. The rock is characterized by low to medium unconfined compressive strength. The alternating bands with varying mineralogical composition differ in mechanical properties and are responding differently to weathering and erosion. This is resulting in the development of minor spalling, pitting etc in the pillars, walls and roofs of the churches. Keeping the geological condition in view remedial measures are to be planned to minimize deterioration with time. -

Tha Battle of Adwa.Book

THE BATTLE OF ADWA THE BATTLE OF ADWA REFLECTIONS ON ETHIOPIA’S HISTORIC VICTORY AGAINST EUROPEAN COLONIALISM Edited by Paulos Milkias & Getachew Metaferia Contributors Richard Pankhurst Zewde Gabra-Selassie Negussay Ayele Harold Marcus Theodore M. Vestal Paulos Milkias Getachew Metaferia Maimire Mennasemay Mesfin Araya Algora Publishing New York © 2005 by Algora Publishing All Rights Reserved www.algora.com No portion of this book (beyond what is permitted by Sections 107 or 108 of the United States Copyright Act of 1976) may be reproduced by any process, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, without the express written permission of the publisher. ISBN: 0-87586-413-9 (softcover) ISBN: 0-87586-414-7 (hardcover) ISBN: 0-87586-415-5 (ebook) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data — The Battle of Adwa: reflections on Ethiopia’s historic victory against European colonialism / edited by Paulos Milkias, Getachew Metaferia. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-87586-413-9 (trade paper: alk. paper) — ISBN 0-87586-414-7 (hard cover: alk. paper) — ISBN 0-87586-415-5 (ebook) 1. Adwa, Battle of, Adwa, Ethiopia, 1896. I. Milkias, Paulos. II. Metaferia, Getachew. DT387.3.B39 2005 963'.043—dc22 2005013845 Front Cover: Printed in the United States This book is dedicated to all peoples of the world who have stood up to colonial subjugation and courageously sacrificed their lives for the love of freedom and liberty ETHIOPIAN TITLES Afe-Nigus — (“Mouthpiece of the Emperor”) equivalent to the U.S. “Chief Justice.” Asiraleqa — (“Commander of 10”) Corporal, as a military title. -

Sediments of Two Gondwana Glaciations in Ethiopia: Provenance of the Enticho Sandstone and the Edaga Arbi Glacials Lewin, Anna (2020)

Sediments of two Gondwana glaciations in Ethiopia: Provenance of the Enticho Sandstone and the Edaga Arbi Glacials Lewin, Anna (2020) DOI (TUprints): https://doi.org/10.25534/tuprints-00013300 License: CC-BY 4.0 International - Creative Commons, Attribution Publication type: Ph.D. Thesis Division: 11 Department of Materials and Earth Sciences Original source: https://tuprints.ulb.tu-darmstadt.de/13300 Sediments of two Gondwana glaciations in Ethiopia: Provenance of the Enticho Sandstone and the Edaga Arbi Glacials Fachbereich Material- und Geowissenschaften der Technischen Universität Darmstadt Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doctor rerum naturalium (Dr.rer.nat.) Von Anna Lewin Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Matthias Hinderer Zweitgutachter: PD Dr. Guido Meinhold Darmstadt, 2020 Anna Lewin geboren am 09.09.1988 in Marl Dissertation Thema: "Sediments of two Gondwana glaciations in Ethiopia: Provenance of the Enticho Sandstone and the Edaga Arbi Glacials” Eingereicht im Mai 2020 Datum der mündlichen Prüfung: 21.07.2020 Referent: Prof. Dr. Matthias Hinderer Korreferent: PD Dr. Guido Meinhold 1. Prüfer: Prof. Dr. Christoph Schüth 2. Prüferin: Prof. Dr. Britta Schmalz Veröffentlichung auf TUprints im Jahr 2020 Veröffentlicht unter CC-BY 4.0 International Prof. Dr. Matthias Hinderer Fachgebiet Sedimentgeologie Institut für Angewandte Geowissenschaften Technische Universität Darmstadt Schnittspahnstraße 9 64287 Darmstadt Ich erkläre hiermit, die vorliegende Dissertation ohne Hilfe Dritter und nur mit den angegebenen Quellen und Hilfsmitteln angefertigt zu haben. Alle Stellen, die aus Quellen übernommen wurden, sind als solche kenntlich gemacht worden. Diese Arbeit hat in dieser oder ähnlicher Form noch keiner Prüfungsbehörde vorgelegen. Die schriftliche Fassung stimmt mit der elektronischen Fassung überein. I hereby certify that the complete work to this PhD thesis was done by myself and only with the use of the referenced literature and the described methods.