The War in Afghanistan at the End of 2012: the Uncertain Course

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GRAND STRATEGY IS ATTRITION: the LOGIC of INTEGRATING VARIOUS FORMS of POWER in CONFLICT Lukas Milevski

GRAND STRATEGY IS ATTRITION: THE LOGIC OF INTEGRATING VARIOUS FORMS OF POWER IN CONFLICT Lukas Milevski FOR THIS AND OTHER PUBLICATIONS, VISIT US AT UNITED STATES https://www.armywarcollege.edu/ ARMY WAR COLLEGE PRESS Carlisle Barracks, PA and ADVANCING STRATEGIC THOUGHT This Publication SSI Website USAWC Website SERIES The United States Army War College The United States Army War College educates and develops leaders for service at the strategic level while advancing knowledge in the global application of Landpower. The purpose of the United States Army War College is to produce graduates who are skilled critical thinkers and complex problem solvers. Concurrently, it is our duty to the U.S. Army to also act as a “think factory” for commanders and civilian leaders at the strategic level worldwide and routinely engage in discourse and debate concerning the role of ground forces in achieving national security objectives. The Strategic Studies Institute publishes national security and strategic research and analysis to influence policy debate and bridge the gap between military and academia. The Center for Strategic Leadership contributes to the education of world class senior leaders, develops expert knowledge, and provides solutions to strategic Army issues affecting the national security community. The Peacekeeping and Stability Operations Institute provides subject matter expertise, technical review, and writing expertise to agencies that develop stability operations concepts and doctrines. The School of Strategic Landpower develops strategic leaders by providing a strong foundation of wisdom grounded in mastery of the profession of arms, and by serving as a crucible for educating future leaders in the analysis, evaluation, and refinement of professional expertise in war, strategy, operations, national security, resource management, and responsible command. -

The Munich Massacre: a New History

The Munich Massacre: A New History Eppie Briggs (aka Marigold Black) A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of BA (Hons) in History University of Sydney October 2011 1 Contents Introduction and Historiography Part I – Quiet the Zionist Rage 1. The Burdened Alliance 2. Domestic Unrest Part II – Rouse the Global Wrath 3. International Condemnation 4. The New Terrorism Conclusion 2 Acknowledgments I would like to thank first and foremost Dr Glenda Sluga to whom I am greatly indebted for her guidance, support and encouragement. Without Glenda‟s sage advice, the writing of this thesis would have been an infinitely more difficult and painful experience. I would also like to thank Dr Michael Ondaatje for his excellent counsel, good-humour and friendship throughout the last few years. Heartfelt thanks go to Elise and Dean Briggs for all their love, support and patience and finally, to Angus Harker and Janie Briggs. I cannot adequately convey the thanks I owe Angus and Janie for their encouragement, love, and strength, and for being a constant reminder as to why I was writing this thesis. 3 Abstract This thesis examines the Nixon administration’s response to the Munich Massacre; a terrorist attack which took place at the 1972 Olympic Games in Munich. By examining the contextual considerations influencing the administration’s response in both the domestic and international spheres, this thesis will determine the manner in which diplomatic intricacies impacted on the introduction of precedent setting counterterrorism institutions. Furthermore, it will expound the correlation between the Nixon administration’s response and a developing conceptualisation of acts of modern international terrorism. -

19 October 2020 "Generated on Refers to the Date on Which the User Accessed the List and Not the Last Date of Substantive Update to the List

Res. 1988 (2011) List The List established and maintained pursuant to Security Council res. 1988 (2011) Generated on: 19 October 2020 "Generated on refers to the date on which the user accessed the list and not the last date of substantive update to the list. Information on the substantive list updates are provided on the Council / Committee’s website." Composition of the List The list consists of the two sections specified below: A. Individuals B. Entities and other groups Information about de-listing may be found at: https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/ombudsperson (for res. 1267) https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/sanctions/delisting (for other Committees) https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/content/2231/list (for res. 2231) A. Individuals TAi.155 Name: 1: ABDUL AZIZ 2: ABBASIN 3: na 4: na ﻋﺒﺪ اﻟﻌﺰﻳﺰ ﻋﺒﺎﺳﯿﻦ :(Name (original script Title: na Designation: na DOB: 1969 POB: Sheykhan Village, Pirkowti Area, Orgun District, Paktika Province, Afghanistan Good quality a.k.a.: Abdul Aziz Mahsud Low quality a.k.a.: na Nationality: na Passport no: na National identification no: na Address: na Listed on: 4 Oct. 2011 (amended on 22 Apr. 2013) Other information: Key commander in the Haqqani Network (TAe.012) under Sirajuddin Jallaloudine Haqqani (TAi.144). Taliban Shadow Governor for Orgun District, Paktika Province as of early 2010. Operated a training camp for non- Afghan fighters in Paktika Province. Has been involved in the transport of weapons to Afghanistan. INTERPOL- UN Security Council Special Notice web link: https://www.interpol.int/en/How-we-work/Notices/View-UN-Notices- Individuals click here TAi.121 Name: 1: AZIZIRAHMAN 2: ABDUL AHAD 3: na 4: na ﻋﺰﯾﺰ اﻟﺮﺣﻤﺎن ﻋﺒﺪ اﻻﺣﺪ :(Name (original script Title: Mr Designation: Third Secretary, Taliban Embassy, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates DOB: 1972 POB: Shega District, Kandahar Province, Afghanistan Good quality a.k.a.: na Low quality a.k.a.: na Nationality: Afghanistan Passport no: na National identification no: Afghan national identification card (tazkira) number 44323 na Address: na Listed on: 25 Jan. -

Afghanistan: Annual Report 2014

AFGHANISTAN ANNUAL REPORT 2014 PROTECTION OF CIVILIANS IN ARMED CONFLICT © 2014/Ihsanullah Mahjoor/Associated Press United Nations Assistance Mission United Nations Office of the High in Afghanistan Commissioner for Human Rights Kabul, Afghanistan February 2015 Kabul, Afghanistan July 2014 Source: UNAMA GIS January 2012 AFGHANISTAN ANNUAL REPORT 2014 PROTECTION OF CIVILIANS IN ARMED CONFLICT United Nations Assistance Mission United Nations Office of the High in Afghanistan Commissioner for Human Rights Kabul, Afghanistan February 2015 Photo on Front Cover © 2014/Ihsanullah Mahjoor/Associated Press. Bodies of civilians killed in a suicide attack on 23 November 2014 in Yahyakhail district, Paktika province that caused 138 civilian casualties (53 killed including 21 children and 85 injured including 26 children). Photo taken on 24 November 2014. "The conflict took an extreme toll on civilians in 2014. Mortars, IEDs, gunfire and other explosives destroyed human life, stole limbs and ruined lives at unprecedented levels. The thousands of Afghan children, women and men killed and injured in 2014 attest to failures to protect civilians from harm. All parties must uphold the values they claim to defend and make protecting civilians their first priority.” Nicholas Haysom, United Nations Special Representative of the Secretary-General in Afghanistan, December 2014, Kabul “This annual report shows once again the unacceptable price that the conflict is exacting on the civilian population in Afghanistan. Documenting these trends should not be regarded -

Syrian Crisis United Nations Response

Syrian Crisis United Nations Response A Weekly Update from the UN Department of Public Information No. 100/ 24 June 2015 Syrians face “unspeakable suffering,” says UN official The Independent Commission of Inquiry on Syria released on 23 June its latest report on the human rights situation in the country, covering the period from 15 March to 15 June. Presenting the report to the Human Rights Council in Geneva, the Chair of the Commission, Paulo Sérgio Pinheiro, said that the conflict in Syria had mutated into a multi-sided and highly fluid war of attrition and civilians remain the main victims of an ever-accelerating cycle of violence, which is causing “unspeakable suffering.” Mr. Pinheiro added that with its superior fire power and control of the skies, the Government inflicted the most damage in its indiscriminate attacks on civilians, and non- state armed groups continued to cause civilian deaths and injuries. The Chairman of the Commission also deplored that “the continuing war represents a profound failure of diplomacy and the absence of action by the international community had nourished a deeply entrenched culture of impunity.” http://www.un.org/apps/news/story.asp?NewsID=51227#.VYmoeEbgW3b More funding needed for Palestine refugees in Lebanon On 22 June, UN Special Coordinator for Lebanon, Sigrid Kaag, called for increased donor assistance to the UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees (UNRWA) to meet the needs of Palestine refugees in Lebanon. Ms. Kaag was speaking during a visit to the Palestinian refugee camp of Burj El-Barajneh, south of Beirut. “Residents of the camp are facing enormous difficulties every day; all possible efforts should be made to give greater support to Palestine refugees here,” she said. -

“They've Shot Many Like This”

HUMAN RIGHTS “They’ve Shot Many Like This” Abusive Night Raids by CIA-Backed Afghan Strike Forces WATCH “They’ve Shot Many Like This” Abusive Night Raids by CIA-Backed Afghan Strike Forces Copyright © 2019 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-37779 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org OCTOBER 2019 ISBN: 978-1-6231-37779 “They’ve Shot Many Like This” Abusive Night Raids by CIA-Backed Afghan Strike Forces Map of Afghanistan ............................................................................................................... i Summary ............................................................................................................................... 1 Recommendations .............................................................................................................. -

My Life with the Taliban

MY LIFE WITH THE TALIBAN ABDUL SALAM ZAEEF My Life with the Taliban Edited by Alex Strick van Linschoten and Felix Kuehn Columbia University Press Publishers Since 1893 New York Chichester, West Sussex Copyright © Abdul Salam Zaeef 2010 Editors’ introduction and translation Copyright © Alex Strick van Linschoten and Felix Kuehn, 2010 Foreword Copyright © Barnett R. Rubin, 2010 All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Za’if, ‘Abd al-Salam, 1967 or 8– My life with the Taliban / Abdul Salam Zaeef. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-231-70148-8 (alk. paper) 1. Za’if, ‘Abd al-Salam, 1967 or 8– 2. Taliban—Biography. 3. Afghan War, 2001—Biography. 4. Prisoners of war—Afghanistan—Biography. 5. Prisoners of war—United States—Biography. 6. Guantánamo Bay Detention Camp—Biography. I. Title. DS371.33.Z34A3 2010 958.104'7—dc22 [B] 2009040865 ∞ Columbia University Press books are printed on permanent and durable acid-free paper. This book is printed on paper with recycled content. Printed in USA c 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 References to Internet Web sites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor Columbia University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared. CONTENTS Kandahar: Portrait of a City ix Editors’ Acknowledgements xxv Editors’ Notes xxvii Character List xxix Foreword by Barnett R. Rubin xxxvii Preface by Abdul Salam Zaeef xli Maps xlviii–xlix 1. Death at Home 1 2. The Camps 13 3. The Jihad 21 4. -

Palestinian Groups

1 Ron’s Web Site • North Shore Flashpoints • http://northshoreflashpoints.blogspot.com/ 2 Palestinian Groups • 1955-Egypt forms Fedayeem • Official detachment of armed infiltrators from Gaza National Guard • “Those who sacrifice themselves” • Recruited ex-Nazis for training • Fatah created in 1958 • Young Palestinians who had fled Gaza when Israel created • Core group came out of the Palestinian Students League at Cairo University that included Yasser Arafat (related to the Grand Mufti) • Ideology was that liberation of Palestine had to preceed Arab unity 3 Palestinian Groups • PLO created in 1964 by Arab League Summit with Ahmad Shuqueri as leader • Founder (George Habash) of Arab National Movement formed in 1960 forms • Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) in December of 1967 with Ahmad Jibril • Popular Democratic Front for the Liberation (PDFLP) for the Liberation of Democratic Palestine formed in early 1969 by Nayif Hawatmah 4 Palestinian Groups Fatah PFLP PDFLP Founder Arafat Habash Hawatmah Religion Sunni Christian Christian Philosophy Recovery of Palestine Radicalize Arab regimes Marxist Leninist Supporter All regimes Iraq Syria 5 Palestinian Leaders Ahmad Jibril George Habash Nayif Hawatmah 6 Mohammed Yasser Abdel Rahman Abdel Raouf Arafat al-Qudwa • 8/24/1929 - 11/11/2004 • Born in Cairo, Egypt • Father born in Gaza of an Egyptian mother • Mother from Jerusalem • Beaten by father for going into Jewish section of Cairo • Graduated from University of King Faud I (1944-1950) • Fought along side Muslim Brotherhood -

The Yom Kippur War: Forty Years Later

The Yom Kippur War: Forty Years Later By HIC research assistant Philip Cane Background Yom Kippur, October 6th 1973, at five minutes past two precisely, 4,000 artillery pieces, 250 aircraft and dozens of FROG missiles1 struck Israeli positions along the Suez Canal and the Sinai, at the same time along the Golan Heights 1,400 tanks2 advanced towards Israel. The equivalent of the total conventional forces of NATO in Europe3, eleven Arab nations4 led by Egypt and Syria had begun an advance into Israeli territory gained in the 1967 Six Day War. The largest Arab-Israeli War would end in an Israeli tactical victory5, but for the first week the fate of Israel itself would be doubted, ‘most Israelis still refer to it as an earthquake that changed the course of the state’s history.’6 The war changed the perceptions of all levels of society in the Middle East and forty years later its ripples are still felt to this day. The Yom Kippur War fell on the holiest day in the Jewish calendar, a Saturday (the Jewish Sabbath) when the alertness of Israeli forces were notably reduced and only a skeleton force7 would be on duty with radio and TV stations shut down hampering mobilisation8. This has led some writers such as Trevor Dupuy and Chaim Herzog to state that this was the primary motive for any such attack9. But it what is not often known is that October 6th is the tenth and holiest day of Ramadan10, when the Prophet Mohammed conquered Mecca which resulted in all of Arabia being Arabic11. -

US-China Strategic Competition in South and East China Seas

U.S.-China Strategic Competition in South and East China Seas: Background and Issues for Congress Updated September 8, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R42784 U.S.-China Strategic Competition in South and East China Seas Summary Over the past several years, the South China Sea (SCS) has emerged as an arena of U.S.-China strategic competition. China’s actions in the SCS—including extensive island-building and base- construction activities at sites that it occupies in the Spratly Islands, as well as actions by its maritime forces to assert China’s claims against competing claims by regional neighbors such as the Philippines and Vietnam—have heightened concerns among U.S. observers that China is gaining effective control of the SCS, an area of strategic, political, and economic importance to the United States and its allies and partners. Actions by China’s maritime forces at the Japan- administered Senkaku Islands in the East China Sea (ECS) are another concern for U.S. observers. Chinese domination of China’s near-seas region—meaning the SCS and ECS, along with the Yellow Sea—could substantially affect U.S. strategic, political, and economic interests in the Indo-Pacific region and elsewhere. Potential general U.S. goals for U.S.-China strategic competition in the SCS and ECS include but are not necessarily limited to the following: fulfilling U.S. security commitments in the Western Pacific, including treaty commitments to Japan and the Philippines; maintaining and enhancing the U.S.-led security architecture in the Western Pacific, including U.S. -

The Rise and Stall of the Islamic State in Afghanistan

UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org SPECIAL REPORT 2301 Constitution Ave., NW • Washington, DC 20037 • 202.457.1700 • fax 202.429.6063 ABOUT THE REPORT Casey Garret Johnson This report details the structure, composition, and growth of the Islamic State’s so-called Khorasan province, particularly in the eastern Afghan province of Nangarhar, and outlines considerations for international policymakers. More than sixty interviews with residents of Nangarhar and provincial and The Rise and Stall of national Afghan security officials carried out by The Liaison Office, an Afghan research and peacebuilding organization, in Nangarhar and Kabul in the spring and summer of 2016 informed this report. the Islamic State in ABOUT THE AUTHOR Afghanistan Casey Garret Johnson is an independent researcher focusing on violent extremism and local politics in Afghanistan. Summary • The Islamic State’s Khorasan province (IS-K) is led by a core of former Tehrik-e-Taliban Paki- stan commanders from Orakzai and Khyber Agencies of Pakistan; the majority of mid-level commanders are former Taliban from Nangarhar, with the rank and file a mixture of local Afghans, Pakistanis, and foreign jihadists mostly from Central Asia. • IS-K receives funding from the Islamic State’s Central Command and is in contact with lead- ership in Iraq and Syria, but the setup and day-to-day operations of the Khorasan province have been less closely controlled than other Islamic State branches such as that in Libya. • IS-K emerged in two separate locations in Afghanistan in 2014—the far eastern reaches of Nangarhar province along the Afghanistan-Pakistan border, and Kajaki district of southern Helmand province. -

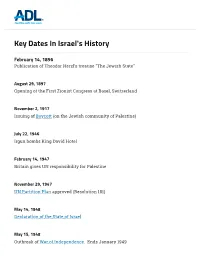

Key Dates in Israel's History

Key Dates In Israel's History February 14, 1896 Publication of Theodor Herzl's treatise "The Jewish State" August 29, 1897 Opening of the First Zionist Congress at Basel, Switzerland November 2, 1917 Issuing of BoBoBoBoyyyycottcottcottcott (on the Jewish community of Palestine) July 22, 1946 Irgun bombs King David Hotel February 14, 1947 Britain gives UN responsibility for Palestine November 29, 1947 UNUNUNUN P PPParararartitiontitiontitiontition Plan PlanPlanPlan approved (Resolution 181) May 14, 1948 DeclarationDeclarationDeclarationDeclaration of ofofof th thththeeee State StateStateState of ofofof Israel IsraelIsraelIsrael May 15, 1948 Outbreak of WWWWarararar of ofofof In InInIndependependependependendendendencececece. Ends January 1949 1 / 11 January 25, 1949 Israel's first national election; David Ben-Gurion elected Prime Minister May 1950 Operation Ali Baba; brings 113,000 Iraqi Jews to Israel September 1950 Operation Magic Carpet; 47,000 Yemeni Jews to Israel Oct. 29-Nov. 6, 1956 Suez Campaign October 10, 1959 Creation of Fatah January 1964 Creation of PPPPalestinalestinalestinalestineeee Liberation LiberationLiberationLiberation Or OrOrOrganizationganizationganizationganization (PLO) January 1, 1965 Fatah first major attack: try to sabotage Israel’s water system May 15-22, 1967 Egyptian Mobilization in the Sinai/Closure of the Tiran Straits June 5-10, 1967 SixSixSixSix Da DaDaDayyyy W WWWarararar November 22, 1967 Adoption of UNUNUNUN Security SecuritySecuritySecurity Coun CounCounCouncilcilcilcil Reso ResoResoResolutionlutionlutionlution