Christopher Mitchell Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Politcal Science

Politcal Science Do Terrorist Beheadings Infuence American Public Opinion? Sponsoring Faculty Member: Dr. John Tures Researchers and Presenters: Lindsey Weathers, Erin Missroon, Sean Greer, Bre’Lan Simpson Addition Researchers: Jarred Adams, Montrell Brown, Braxton Ford, Jefrey Garner, Jamarkis Holmes, Duncan Parker, Mark Wagner Introduction At the end of Summer 2014, Americans were shocked to see the tele- vised execution of a pair of American journalists in Syria by a group known as ISIS. Both were killed in gruesome beheadings. The images seen on main- stream media sites, and on websites, bore an eerie resemblance to beheadings ten years earlier in Iraq. During the U.S. occupation, nearly a dozen Americans were beheaded, while Iraqis and people from a variety of countries were dis- patched in a similar manner. Analysts still question the purpose of the videos of 2004 and 2014. Were they designed to inspire locals to join the cause of those responsible for the killings? Were they designed to intimidate the Americans and coalition members, getting the public demand their leaders withdraw from the region? Or was it some combination of the two ideas? It is difcult to assess the former. But we can see whether the behead- ings had any infuence upon American public opinion. Did they make Ameri- cans want to withdraw from the Middle East? And did the beheadings afect the way Americans view Islam? To determine answers to these questions, we look to the literature for theories about U.S. public opinion, as well as infuences upon it. We look at whether these beheadings have had an infuence on survey data of Americans across the last dozen years. -

Information on Tanzim Qa'idat Al-Jihad Fi Bilad Al-Rafidayn

Tanzim Qa'idat al-Jihad fi Bilad al-Rafidayn. Also known as: the al-Zarqawi network; al-Tawhid; Jama'at al-Tawhid wa'al-Jihad; Al-Tawhid and al-Jihad; The Monotheism and Jihad Group; Qaida of the Jihad in the Land of the Two rivers; Ai-Qa'ida of Jihad in the Land of the Two Rivers; Al-Qa'ida of Jihad Organization in the Land of the Two Rivers; The Organisation of Jihad's Base in the Country of the Two Rivers; The Organisation Base of Jihad/Country of the Two Rivers; The Organisation Base of Jihad/Mesopotamia; Tanzeem Qa'idat al- Jihad/Bilad al Raafidaini; Kateab al-Tawhid; Brigades of Tawhid; Unity and Jihad Group; Unity and Holy Struggle; Unity and Holy War. The following information is based on publicly available details about Tanzim Qa'idat al- Jihad fi Bilad al-Rafidayn (TQJBR). These details have been corroborated by material from intelligence investigations into the activities of the TQJBR and by official reporting. The Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO) assesses that the details set out below are accurate and reliable. TQJBR has been proscribed as a terrorist organisation by the United Nations and the United States Government. Background TQJBR is a Sunni Islamist extremist network established and led by Abu Mus'ab al- Zarqawi.1 The network first emerged as a loose-knit grouping of individuals and organisations under the leadership of al-Zarqawi over a period of several years, following his release from a Jordanian prison in 1999. On 24 April 2004 it was publicly proclaimed under the name Jama'at al-Tawhid wa'al-Jihad in an internet statement attributed to al-Zarqawi. -

Congressional Record—House H4628

H4628 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — HOUSE June 21, 2004 The ideology behind this is that Iraq in this last hour. And I appreciate the very important, very important. In the was the key to being able to move into discussion with my colleagues. And if 1990s Osama bin Laden in the Sudan Syria, being able to move into Iran, we have the time, I will be happy to had 13 terrorists training camps around that this is somehow a defense of the yield to them. It seems like we prob- Khartoum. Our intelligence agencies Likud version of what is in Israel’s in- ably will have the time. talked about that. The President and terest. The so-called neoconservatives There is no question, none at all, the NSC knew about that. And at that that are behind this ideological thrust that al-Qaeda and the Saddam Hussein time, we had an attack on the World have wanted this war for years. It is regime and people connected with that Trade Center because Osama bin not hidden. It is not a conspiracy. It is have met on numerous occasions. Laden’s minions tried to bring it down. not some kind of subterfuge. It is an There is no question that in May of That was in 1993. In 1996, we had the at- announced policy and possession philo- 2002, Zarqawi, one of the top lieuten- tack that killed a lot of Americans in sophically they have had for years. ants the senior al-Qaeda with bin Khobar Towers. In 1998, we had the at- The sad part is after Mr. -

Terror in the Name of Islam - Unholy War, Not Jihad Parvez Ahmed

Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law Volume 39 Issue 3 2007-2008 2008 Terror in the Name of Islam - Unholy War, Not Jihad Parvez Ahmed Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/jil Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Parvez Ahmed, Terror in the Name of Islam - Unholy War, Not Jihad, 39 Case W. Res. J. Int'l L. 759 (2008) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/jil/vol39/iss3/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. TERROR IN THE NAME OF ISLAM-UNHOLY WAR, NOT JIHAD Parvez Ahmeaf t Every gun that is made, every warship launched, every rocket fired signi- fies, in the final sense, a theft from those who hunger and are not fed, those who are cold and are not clothed This world in arms is not spending money alone. It is spending the sweat of its laborers, the genius of its scientists, the hopes of its children. This is not a way of life at all, in any war, it is humanity hanging true sense. Under the1 cloud of threatening from a cross of iron. I. INTRODUCTION The objective of this paper is to (1) analyze current definitions of terrorism, (2) explore the history of recent terrorism committed in the name of Islam, (3) posit causal links between terrorism and the United States' (U.S.) Cold War programs and policies towards the Middle East, and (4) propose remedies to minimize and preferably eliminate the threat of terror- ism. -

Iraq's Evolving Insurgency

CSIS _______________________________ Center for Strategic and International Studies 1800 K Street N.W. Washington, DC 20006 (202) 775 -3270 Access: Web: CSIS.ORG Contact the Author: [email protected] Iraq’s Evolving Insurgency Anthony H. Cordesman Center for Strategic and International Studies With the Assistance of Patrick Baetjer Working Draft: Updated as of August 5, 2005 Please not e that this is part of a rough working draft of a CSIS book that will be published by Praeger in the fall of 2005. It is being circulated to solicit comments and additional data, and will be steadily revised and updated over time. Copyright CSIS, all rights reserved. All further dissemination and reproduction must be done with the written permission of the CSIS Cordesman: Iraq’s Evolving Insurgency 8/5/05 Page ii I. INTR ODUCTION ................................ ................................ ................................ ................................ ..... 1 SADDAM HUSSEIN ’S “P OWDER KEG ” ................................ ................................ ................................ ......... 1 AMERICA ’S STRATEGIC MISTAKES ................................ ................................ ................................ ............. 2 AMERICA ’S STRATEGIC MISTAKES ................................ ................................ ................................ ............. 6 II. THE GROWTH AND C HARACTER OF THE INSURGENT THREA T ................................ ........ 9 DENIAL AS A METHOD OF COUNTER -INSURGENCY WARFARE ............................... -

Terrorist Beheadings: Cultural and Strategic Implications

TERRORIST BEHEADINGS: CULTURAL AND STRATEGIC IMPLICATIONS Ronald H. Jones June 2005 Visit our website for other free publication downloads http://www.carlisle.army.mil/ssi To rate this publication click here. ***** The views expressed in this report are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government. This report is cleared for public release; distribution is unlimited. ***** Comments pertaining to this report are invited and should be forwarded to: Director, Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army War College, 122 Forbes Ave, Carlisle, PA 17013-5244. ***** All Strategic Studies Institute (SSI) monographs are available on the SSI Homepage for electronic dissemination. Hard copies of this report also may be ordered from our Homepage. SSI’s Homepage address is: http://www.carlisle.army.mil/ssi/ ***** The Strategic Studies Institute publishes a monthly e-mail newsletter to update the national security community on the research of our analysts, recent and forthcoming publications, and upcoming conferences sponsored by the Institute. Each newsletter also provides a strategic commentary by one of our research analysts. If you are interested in receiving this newsletter, please subscribe on our homepage at http://www.carlisle.army.mil/ssi/newsletter.cfm. ISBN 1-58487-207-1 ii PREFACE The U.S. Army War College provides an excellent environment for selected military officers and government civilians to reflect and use their career experience to explore a wide range of strategic issues. To assure that the research developed by Army War College students is available to Army and Department of Defense leaders, the Strategic Studies Institute publishes selected papers in its Carlisle Papers in Security Strategy Series. -

A Theory of ISIS

A Theory of ISIS A Theory of ISIS Political Violence and the Transformation of the Global Order Mohammad-Mahmoud Ould Mohamedou First published 2018 by Pluto Press 345 Archway Road, London N6 5AA www.plutobooks.com Copyright © Mohammad-Mahmoud Ould Mohamedou 2018 The right of Mohammad-Mahmoud Ould Mohamedou to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7453 9911 9 Hardback ISBN 978 0 7453 9909 6 Paperback ISBN 978 1 7868 0169 2 PDF eBook ISBN 978 1 7868 0171 5 Kindle eBook ISBN 978 1 7868 0170 8 EPUB eBook This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. Logging, pulping and manufacturing processes are expected to conform to the environmental standards of the country of origin. Typeset by Stanford DTP Services, Northampton, England Simultaneously printed in the United Kingdom and United States of America Contents List of Figures vii List of Tables viii List of Abbreviations ix Acknowledgements x Introduction: The Islamic State and Political Violence in the Early Twenty-First Century 1 Misunderstanding IS 6 Genealogies of New Violence 22 Theorising IS 28 1. Al Qaeda’s Matrix 31 Unleashing Transnational Violence 32 Revenge of the ‘Agitated Muslims’ 49 The McDonaldisation of Terrorism 57 2. Apocalypse Iraq 65 Colonialism Redesigned 66 Monstering in American Iraq 74 ‘I will see you in New York’ 83 3. -

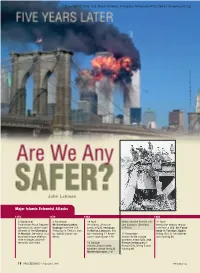

John Lehman Institute L a V Na

Copyright © 2006, U.S. Naval Institute, Annapolis, Maryland (410) 268-6110 www.usni.org /) S r E w to m/ co . es y E r fou (www. ittek w ch K. S A r A 2001 S © E v chi r A photo John Lehman institute l A v na Major Islamic Extremist Attacks U.S. 1972 1979 1983 1984 5 September 4 November 18 April killed) and the French mili- 12 April Palestinian Black Septem- 66 Americans taken An Islamic Jihad car tary barracks (50 killed) Hezbollah attacks restau- ber terrorists seize Israeli hostage from the U.S. bomb at U.S. embassy in Beirut. rant near a U.S. Air Force athletes at the Olympics Embassy in Tehran, Iran, in Beirut, Lebanon, kills base in Torrejon, Spain, in Munich, Germany. In a by radical Iranian stu- 63—including 17 Ameri- 12 December killing 18 U.S. servicemen botched rescue attempt, dents. cans—and injures 120. Iranian Shiite suicide and injuring 83. nine hostages and five bombers attack U.S. and terrorists are killed. 23 October French embassies in Islamic Jihad suicide Kuwait City, killing 5 and bombers attack the U.S. injuring 86. Marine barracks (241 18 PROCEEDINGS • September 2006 www.usni.org A former secretary of the Navy and member of the 9/11 Commission identifies the real enemy in the current war and assesses progress. re we winning the war? The first question to what happened in the attacks on 11 September 2001, ask is what war? The administration of Presi- how they were organized and executed, and who was dent George W. -

Death in Wartime: Photographs and the "Other War" in Afghanistan

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Departmental Papers (ASC) Annenberg School for Communication 1-1-2005 Death in Wartime: Photographs and the "Other War" in Afghanistan Barbie Zelizer University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers Part of the Journalism Studies Commons Recommended Citation Zelizer, B. (2005). Death in Wartime: Photographs and the "Other War" in Afghanistan. The Harvard International Journal of Press/Politics, 10 (3), 26-55. https://doi.org/10.1177/1081180X05278370 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers/68 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Death in Wartime: Photographs and the "Other War" in Afghanistan Abstract This article addresses the formulaic dependence of the news media on images of people facing impending death. Considering one example of this depiction — U.S. journalism's photographic coverage of the killing of the Taliban by the Northern Alliance during the war on Afghanistan, the article traces its strategic appearance and recycling across the U.S. news media and shows how the beatings and deaths of the Taliban were depicted in ways that fell short of journalism's proclaimed objective of fully documenting the events of the war. The article argues that in so doing, U.S. journalism failed to raise certain questions about the nature of the alliance between the United States and its allies on Afghanistan's northern front. Disciplines Journalism Studies This journal article is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers/68 Death in Wartime Photographs and the "Other War" in Afghanistan Barbie Zelizer This article addresses the formulaic dependence of the news media on images of people facing impending death. -

Radical Solution to Radical Extremism

Radical Solution to Radical Extremism May 23, 2004 By Robbie Friedmann The corrupt criminal murderer who still passes for a world leader - elevated to a Nobel Peace Prize winner - realizes full well the world still does not get it. He wants to destroy Israel, and the world (and Israel) is letting him get away with it ("Arafat: 'No One in This World Has the Right to Concede the Refugees' Right to Return to Their Homeland; The Palestinian Heroes Will Fight for This Right,'" MEMRI, Special Dispatch No. 717, 19 May 2004). So much for the Geneva Accord, which his Israeli counterparts hailed as a major achievement since the Palestinians have "given up their 'right of return.'" He continues to guide hate sermons from mosques ("PA Politicians Direct Mosque Hate Sermons," Itamar Marcus, Palestinian Media Watch Bulletin, 16 May 2004) and summons the Palestinian masses to battle. After all, what is a million more or less of his people for him ("PA called Women, Children and Elderly to Wednesday's Battle," Itamar Marcus and Barbara Crook, Palestinian Media Watch Bulletin, 20 May 2004)? And the price he pays for this? After almost four years of terror (not counting the 36 years of terror he initiated beforehand), thousands of Israeli casualties and many American ones as well, he and the Palestinians have "lost the sympathy" of some in the Israeli Left ("The Death of Sympathy," Larry Derfner, Jerusalem Post, 16 May 2004). Now he must be really scared. As if sympathy is what he has been after. And from the Israeli Left. -

Congressional Record—House H2884

H2884 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — HOUSE May 12, 2004 missiles that can reach the United are dealing with terrorists on sophisti- and they do not reflect what is going States, and have this country instantly cated manned pads that can shoot on in Iraq. Because there are magnifi- incinerated. down airliners, they are dealing in nu- cent tales of sacrifice and commitment b 1930 clear technology to terrorist nations. going on in Iraq. Our friends, the Chinese. The Bush ad- For those people who wonder why the That is not the threat. The threat is ministration says, if we only embrace Secretary of Defense should not step a tanker, a freighter, a truck coming them a little tighter, they will come down, it has not been that long ago, across the border, or something being around. Yeah, right, after they get all Mr. Speaker, that we saw Rodney King smuggled in some other way. But we our money, all our jobs, and all our in those famous videos where members are doing nothing to protect against technology, they will come around? of the Los Angeles Police Department that. We are going to spend the money. I am just getting tired of these ex- were beating him. That circumstance Why? Because the defense contractors cuses: that if only they were in charge, did not reflect the policemen in L.A. are making a bundle, and then they they would do better. We have a failed any more than our current actions re- turn around and give a cut to the Re- trade policy, and what has this Presi- flect our soldiers in Iraq. -

American Beheaded Panel Discusses Associated Press Writer Video As Nick Berg, a 26-Year-Old Philadelphia Zarqawi Also Is Sought in the Assassination of a a Native

SERVING SAN JOSE STATE UNIVERSITY SINCE 1934 SPARTAN DAILY VOLUME 122, NUMBER 66 WWW.THESPARTANDAILY.COM WEDNESDAY, MAY 12, 2004 American beheaded Panel discusses Associated Press Writer video as Nick Berg, a 26-year-old Philadelphia Zarqawi also is sought in the assassination of a a native. His body was found near a highway U.S. diplomat in Jordan in 2002. BAGHDAD, Iraq A video posted overpass in Baghdad on Saturday, the same day The Bush administration said of those who experiences Tuesday on an al-Qaida-linked Web site showed he was beheaded, a U.S. official said. beheaded Berg would be hunted down and the beheading of an American civilian in Iraq The video bore the title "Abu Musab al- brought to justice. a and said the execution was carried out to avenge Zarqawi shown slaughtering an American." It "Our thoughts and prayers are with his abuses of Iraqi prisoners at Abu Ghraib prison. was unclear whether al-Zarqawi an associate family," White House Press Secretary Scott working in Iraq In a grisly gesture, the executioners held up of Osama bin Laden believed behind the wave McClellan said. "It shows the true nature of the the man's head for the camera. of suicide bombings in Iraq was shown in The American identified himself on the the video or simply ordered the execution. Al- see BERG, page 7 Voting begins in fee referendum Nicholas R. right / Daily Staff Dr. Assad Hassoun, right, a native of Babylon and a transplant surgeon at the California Pacific Medical Center, gives his opinions about the situation in Iraq during a panel discussion in the Dr.