Appalachian Oak Forest, #104

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Department of Planning and Zoning

Department of Planning and Zoning Subject: Howard County Landscape Manual Updates: Recommended Street Tree List (Appendix B) and Recommended Plant List (Appendix C) - Effective July 1, 2010 To: DLD Review Staff Homebuilders Committee From: Kent Sheubrooks, Acting Chief Division of Land Development Date: July 1, 2010 Purpose: The purpose of this policy memorandum is to update the Recommended Plant Lists presently contained in the Landscape Manual. The plant lists were created for the first edition of the Manual in 1993 before information was available about invasive qualities of certain recommended plants contained in those lists (Norway Maple, Bradford Pear, etc.). Additionally, diseases and pests have made some other plants undesirable (Ash, Austrian Pine, etc.). The Howard County General Plan 2000 and subsequent environmental and community planning publications such as the Route 1 and Route 40 Manuals and the Green Neighborhood Design Guidelines have promoted the desirability of using native plants in landscape plantings. Therefore, this policy seeks to update the Recommended Plant Lists by identifying invasive plant species and disease or pest ridden plants for their removal and prohibition from further planting in Howard County and to add other available native plants which have desirable characteristics for street tree or general landscape use for inclusion on the Recommended Plant Lists. Please note that a comprehensive review of the street tree and landscape tree lists were conducted for the purpose of this update, however, only -

Native Trees of Georgia

1 NATIVE TREES OF GEORGIA By G. Norman Bishop Professor of Forestry George Foster Peabody School of Forestry University of Georgia Currently Named Daniel B. Warnell School of Forest Resources University of Georgia GEORGIA FORESTRY COMMISSION Eleventh Printing - 2001 Revised Edition 2 FOREWARD This manual has been prepared in an effort to give to those interested in the trees of Georgia a means by which they may gain a more intimate knowledge of the tree species. Of about 250 species native to the state, only 92 are described here. These were chosen for their commercial importance, distribution over the state or because of some unusual characteristic. Since the manual is intended primarily for the use of the layman, technical terms have been omitted wherever possible; however, the scientific names of the trees and the families to which they belong, have been included. It might be explained that the species are grouped by families, the name of each occurring at the top of the page over the name of the first member of that family. Also, there is included in the text, a subdivision entitled KEY CHARACTERISTICS, the purpose of which is to give the reader, all in one group, the most outstanding features whereby he may more easily recognize the tree. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author wishes to express his appreciation to the Houghton Mifflin Company, publishers of Sargent’s Manual of the Trees of North America, for permission to use the cuts of all trees appearing in this manual; to B. R. Stogsdill for assistance in arranging the material; to W. -

Quercus Coccinea.Indd

Quercus coccinea (Scarlet Oak) Beech Family (Fagaceae) Introduction: Scarlet oak is a member of the red oak group with lobed leaves and is valued for its ornamental attributes as well as its fi ne wood. It is considered an excellent alternative to the overplanted pin oak because it is beautiful throughout the year and tolerates alkaline soil. Culture: Scarlet oak makes an excellent lawn or park tree. It thrives in full sun and well-drained, acidic soil. This tree is less susceptible to chlorosis problems than pin oak. Potential problems on oaks in general include obscure scale, two-lined chestnut borer, bacterial leaf scorch, oak horn gall and gypsy moth. In addition, as little as 1 inch of fi ll soil can kill an oak. Botanical Characteristics: Additional information: Scarlet oak is appropriately named for its Native habit: Maine south to Florida, west to extraordinary leaf color in early spring and in autumn. Minnesota and Missouri. Its delicate branching pattern combined with nearly black bark and persistent leaves make this an exceptional tree Growth habit: Scarlet oak has a rounded, open even in winter. form at maturity. Although scarlet oak has a predominant tap root, it does have some spreading lateral roots, making the tree Tree size: This oak can attain a height of 70 to easier to transplant than some oaks. It is best to transplant 75 feet and a width of 40 to 50 feet. It can reach a the tree in the fall. The lateral roots may appear above the height of 100 feet in the wild. -

Introduction to the Southern Blue Ridge Ecoregional Conservation Plan

SOUTHERN BLUE RIDGE ECOREGIONAL CONSERVATION PLAN Summary and Implementation Document March 2000 THE NATURE CONSERVANCY and the SOUTHERN APPALACHIAN FOREST COALITION Southern Blue Ridge Ecoregional Conservation Plan Summary and Implementation Document Citation: The Nature Conservancy and Southern Appalachian Forest Coalition. 2000. Southern Blue Ridge Ecoregional Conservation Plan: Summary and Implementation Document. The Nature Conservancy: Durham, North Carolina. This document was produced in partnership by the following three conservation organizations: The Nature Conservancy is a nonprofit conservation organization with the mission to preserve plants, animals and natural communities that represent the diversity of life on Earth by protecting the lands and waters they need to survive. The Southern Appalachian Forest Coalition is a nonprofit organization that works to preserve, protect, and pass on the irreplaceable heritage of the region’s National Forests and mountain landscapes. The Association for Biodiversity Information is an organization dedicated to providing information for protecting the diversity of life on Earth. ABI is an independent nonprofit organization created in collaboration with the Network of Natural Heritage Programs and Conservation Data Centers and The Nature Conservancy, and is a leading source of reliable information on species and ecosystems for use in conservation and land use planning. Photocredits: Robert D. Sutter, The Nature Conservancy EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This first iteration of an ecoregional plan for the Southern Blue Ridge is a compendium of hypotheses on how to conserve species nearest extinction, rare and common natural communities and the rich and diverse biodiversity in the ecoregion. The plan identifies a portfolio of sites that is a vision for conservation action, enabling practitioners to set priorities among sites and develop site-specific and multi-site conservation strategies. -

2005 Forest Ecosystem Study Unit

TABLE OF CONTENTS Forest Ecosystems............................................................................................................... 1 What is an ecosystem?.................................................................................................... 2 Ecosystem Classification ................................................................................................ 2 What is a forest?.............................................................................................................. 5 What are the different kinds of forests?.......................................................................... 5 Why do we need forests? ................................................................................................ 6 What are the layers of a forest?....................................................................................... 8 Ecological Succession......................................................................................................... 9 How Forest Ecosystems Change..................................................................................... 9 Stages of Succession..................................................................................................... 10 How Succession Affects Energy Flow ......................................................................... 12 Species Characteristic of Georgia’s Ecosystems .......................................................... 13 Tree Identification........................................................................................................ -

Ecological Zones in the Southern Appalachians: First Approximation

United States Department of Ecological Zones in the Southern Agriculture Forest Service Appalachians: First Approximation Steve A. Simon, Thomas K. Collins, Southern Gary L. Kauffman, W. Henry McNab, and Research Station Christopher J. Ulrey Research Paper SRS–41 The Authors Steven A. Simon, Ecologist, USDA Forest Service, National Forests in North Carolina, Asheville, NC 28802; Thomas K. Collins, Geologist, USDA Forest Service, George Washington and Jefferson National Forests, Roanoke, VA 24019; Gary L. Kauffman, Botanist, USDA Forest Service, National Forests in North Carolina, Asheville, NC 28802; W. Henry McNab, Research Forester, USDA Forest Service, Southern Research Station, Asheville, NC 28806; and Christopher J. Ulrey, Vegetation Specialist, U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Blue Ridge Parkway, Asheville, NC 28805. Cover Photos Ecological zones, regions of similar physical conditions and biological potential, are numerous and varied in the Southern Appalachian Mountains and are often typified by plant associations like the red spruce, Fraser fir, and northern hardwoods association found on the slopes of Mt. Mitchell (upper photo) and characteristic of high-elevation ecosystems in the region. Sites within ecological zones may be characterized by geologic formation, landform, aspect, and other physical variables that combine to form environments of varying temperature, moisture, and fertility, which are suitable to support characteristic species and forests, such as this Blue Ridge Parkway forest dominated by chestnut oak and pitch pine with an evergreen understory of mountain laurel (lower photo). DISCLAIMER The use of trade or firm names in this publication is for reader information and does not imply endorsement of any product or service by the U.S. -

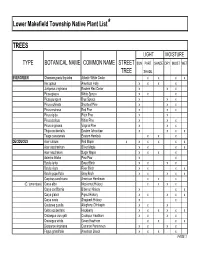

Native Plant List Trees.XLS

Lower Makefield Township Native Plant List* TREES LIGHT MOISTURE TYPE BOTANICAL NAME COMMON NAME STREET SUN PART SHADE DRY MOIST WET TREE SHADE EVERGREEN Chamaecyparis thyoides Atlantic White Cedar x x x x IIex opaca American Holly x x x x Juniperus virginiana Eastern Red Cedar x x x Picea glauca White Spruce x x x Picea pungens Blue Spruce x x x Pinus echinata Shortleaf Pine x x x Pinus resinosa Red Pine x x x Pinus rigida Pitch Pine x x Pinus strobus White Pine x x x Pinus virginiana Virginia Pine x x x Thuja occidentalis Eastern Arborvitae x x x x Tsuga canadensis Eastern Hemlock xx x DECIDUOUS Acer rubrum Red Maple x x x x x x Acer saccharinum Silver Maple x x x x Acer saccharum Sugar Maple x x x x Asimina triloba Paw-Paw x x Betula lenta Sweet Birch x x x x Betula nigra River Birch x x x x Betula populifolia Gray Birch x x x x x Carpinus caroliniana American Hornbeam x x x (C. tomentosa) Carya alba Mockernut Hickory x x x x Carya cordiformis Bitternut Hickory x x x Carya glabra Pignut Hickory x x x x x Carya ovata Shagbark Hickory x x Castanea pumila Allegheny Chinkapin xx x Celtis occidentalis Hackberry x x x x x x Crataegus crus-galli Cockspur Hawthorn x x x x Crataegus viridis Green Hawthorn x x x x Diospyros virginiana Common Persimmon x x x x Fagus grandifolia American Beech x x x x PAGE 1 Exhibit 1 TREES (cont'd) LIGHT MOISTURE TYPE BOTANICAL NAME COMMON NAME STREET SUN PART SHADE DRY MOIST WET TREE SHADE DECIDUOUS (cont'd) Fraxinus americana White Ash x x x x Fraxinus pennsylvanica Green Ash x x x x x Gleditsia triacanthos v. -

An Updated Infrageneric Classification of the North American Oaks

Article An Updated Infrageneric Classification of the North American Oaks (Quercus Subgenus Quercus): Review of the Contribution of Phylogenomic Data to Biogeography and Species Diversity Paul S. Manos 1,* and Andrew L. Hipp 2 1 Department of Biology, Duke University, 330 Bio Sci Bldg, Durham, NC 27708, USA 2 The Morton Arboretum, Center for Tree Science, 4100 Illinois 53, Lisle, IL 60532, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The oak flora of North America north of Mexico is both phylogenetically diverse and species-rich, including 92 species placed in five sections of subgenus Quercus, the oak clade centered on the Americas. Despite phylogenetic and taxonomic progress on the genus over the past 45 years, classification of species at the subsectional level remains unchanged since the early treatments by WL Trelease, AA Camus, and CH Muller. In recent work, we used a RAD-seq based phylogeny including 250 species sampled from throughout the Americas and Eurasia to reconstruct the timing and biogeography of the North American oak radiation. This work demonstrates that the North American oak flora comprises mostly regional species radiations with limited phylogenetic affinities to Mexican clades, and two sister group connections to Eurasia. Using this framework, we describe the regional patterns of oak diversity within North America and formally classify 62 species into nine major North American subsections within sections Lobatae (the red oaks) and Quercus (the Citation: Manos, P.S.; Hipp, A.L. An Quercus Updated Infrageneric Classification white oaks), the two largest sections of subgenus . We also distill emerging evolutionary and of the North American Oaks (Quercus biogeographic patterns based on the impact of phylogenomic data on the systematics of multiple Subgenus Quercus): Review of the species complexes and instances of hybridization. -

Native Plant List TABLE 1: Species for Tree and Shrub Plantings Trees For

Native Plant List TABLE 1: Species for Tree and Shrub Plantings Trees for Dry-Open Sites Scientific Name Common Name Mature Height Betula populifolia Gray Birch 30' Juniperis virginiana Eastern Red Cedar 10-75' Pinus resinosa Red Pine 70' Pin us rigida Pitch Pine 50' Pinus stro bus White Pine 80' Quercus rubra Red Oak 70' Quercus coccinea Scarlet Oak 70' Quercus velutina Black Oak 70' Shrubs for Dry-Open Sites Scientific Name 'Common Name Mature Height Amelanchier canadensis Shadbush 15' Ceanothus americanus New Jersey Tea 4' Comptonia peregrina Sweetfern 4' Cornus racemosa Gray Dogwood 6-10' Gaylussacia baccata Black Huckleberry l' Hypericum prolificum Shrubby St. Johnswort 4' Juniperus communis Pasture Juniper 2' Myrica pensylvanica Bayberry 6' Prunus maritima Beach plum 6' Rhus aromatica Fragrant Sumac 3' Rhus copallina Shining Sumac 4-10' Rhus glabra Smooth Sumac 9-15' Rosa carolina Pasture Rose 3' Rosa virginiana Virginia Rose 3' Spirea tomentosa Steeplebush 3-4' Viburnum dentatum/recognitum Arrowwood 5-8' Viburnum lentago Nannyberry 15' Shrubs For Dry-Shady Sites Scientific Name Common Name Mature Height Hamamelis wrginiana Witch Hazel 15' Kalmia latifolia Mountain Laurel 3-8' Rhododendron nudiflorum Pinxterbloom Azalea 4-6' Vaccinium angustifolium Lowbush Blueberry 2' Viburnum dentatum Arrowwood 5-8' Trees For Moist Sites Scientific Name Common Name Mature Height Acer rubrum Red Maple 60' Betula nigra River Birch Chamaecyparis thyoides Atlantic White Cedar Fraxinus pennsylvanica Green Ash 60' Picea mariana Black Spruce 40' Picea -

Stem, Branch, and Root Wood Anatomy of Black Oak (Quercus Velutina Lam) Douglas D

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1986 Stem, branch, and root wood anatomy of black oak (Quercus velutina Lam) Douglas D. Stokke Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Agriculture Commons, and the Wood Science and Pulp, Paper Technology Commons Recommended Citation Stokke, Douglas D., "Stem, branch, and root wood anatomy of black oak (Quercus velutina Lam) " (1986). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 8312. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/8312 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. For example: • Manuscript pages may have indistinct print. In such cases, the best available copy has been filmed. • Manuscripts may not always be complete. In such cases, a note will indicate that it is not possible to obtain missing pages. • Copyrighted material may have been removed from the manuscript. In such cases, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, and charts) are photographed by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

The Distribution of the Genus Quercus in Illinois: an Update

Transactions of the Illinois State Academy of Science received 3/19/02 (2002), Volume 95, #4, pp. 261-284 accepted 6/23/02 The Distribution of the Genus Quercus in Illinois: An Update Nick A. Stoynoff Glenbard East High School Lombard, IL 60148 William J. Hess The Morton Arboretum Lisle, IL 60532 ABSTRACT This paper updates the distribution of members of the black oak [section Lobatae] and white oak [section Quercus] groups native to Illinois. In addition a brief discussion of Illinois’ spontaneously occurring hybrid oaks is presented. The findings reported are based on personal collections, herbarium specimens, and published documents. INTRODUCTION The genus Quercus is well known in Illinois. Although some taxa are widespread, a few have a limited distribution. Three species are of “special concern” and are listed as either threatened (Quercus phellos L., willow oak; Quercus montana Willd., rock chestnut oak) or endangered (Quercus texana Buckl., Nuttall’s oak) [Illinois Endangered Species Pro- tection Board 1999]. The Illinois Natural History Survey has dedicated a portion of its website [www.INHS.uiuc.edu] to the species of Quercus in Illinois. A discussion of all oaks from North America is available online from the Flora of North America Associa- tion [http://hua.huh.harvard.edu/FNA/] and in print [Jensen 1997, Nixon 1997, Nixon and Muller 1997]. The National Plant Data Center maintains an extensive online database [http://plants.usda.gov] documenting information on plants in the United States and its territories. Extensive oak data are available there [U.S.D.A. 2001]. During the last 40 years the number of native oak species recognized for Illinois by vari- ous floristic authors has varied little [Tables 1 & 2]. -

Chestnut Oak Forest (Dry Heath Subtype)

CHESTNUT OAK FOREST (DRY HEATH SUBTYPE) Concept: Chestnut Oak Forest communities are forests of mountain and foothill dry slopes and ridges at low to moderate elevation, dominated by Quercus montana, sometimes in combination with Quercus coccinea or Quercus rubra, but lacking Quercus alba. Castanea dentata was once dominant or codominant. The Dry Heath Subtype encompasses the common examples with extensive shrub layers dominated by Kalmia latifolia or any of several Gaylussacia or Vaccinium species. Distinguishing Features: Chestnut Oak Forest is distinguished from all other mountain community types by the dominance of Quercus montana, alone or in combination with Quercus coccinea, Quercus rubra, or Acer rubrum. Forests with Quercus alba present in more than very small numbers are treated as Montane Oak–Hickory Forest instead, even if Quercus montana is more abundant. Chestnut Oak Forest is distinguished from Piedmont Monadnock Forest by occurrence in the Mountain Region or mountain-like foothills and by having a component of species not typical in the Piedmont. These include Castanea dentata, Rhododendron calendulaceum, Pyrularia pubera, Gaylussacia ursina, Kalmia latifolia, Carex pensylvanica, and usually, Gaylussacia baccata. Chestnut Oak Forest is distinguished from Pine—Oak/Heath and Low Mountain Pine Forest by having less yellow pine than oak in the canopy. A few transitional examples may have a substantial minority of pine. The relationship between the Dry Heath Subtype and the pine communities may be confused by the long absence of fire and by pine mortality caused by southern pine beetle. Areas of recent pine mortality tend to have broken canopies in which understory species such as Nyssa sylvatica and Oxydendrum arboreum are as numerous in the canopy as the oaks, but some examples may be ambiguous.