Mountain Oak Forests Occur on Blue Ridge and Foothills Slopes and Ridges and Are Dominated by Various Species of Quercus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neighborwoods Right Plant, Right Place Plant Selection Guide

“Right Plant, Right Place” Plant Selection Guide Compiled by Samuel Kelleher, ASLA April 2014 - Shrubs - Sweet Shrub - Calycanthus floridus Description: Deciduous shrub; Native; leaves opposite, simple, smooth margined, oblong; flowers axillary, with many brown-maroon, strap-like petals, aromatic; brown seeds enclosed in an elongated, fibrous sac. Sometimes called “Sweet Bubba” or “Sweet Bubby”. Height: 6-9 ft. Width: 6-12 ft. Exposure: Sun to partial shade; range of soil types Sasanqua Camellia - Camellia sasanqua Comment: Evergreen. Drought tolerant Height: 6-10 ft. Width: 5-7 ft. Flower: 2-3 in. single or double white, pink or red flowers in fall Site: Sun to partial shade; prefers acidic, moist, well-drained soil high in organic matter Yaupon Holly - Ilex vomitoria Description: Evergreen shrub or small tree; Native; leaves alternate, simple, elliptical, shallowly toothed; flowers axillary, small, white; fruit a red or rarely yellow berry Height: 15-20 ft. (if allowed to grow without heavy pruning) Width: 10-20 ft. Site: Sun to partial shade; tolerates a range of soil types (dry, moist) Loropetalum ‘ZhuZhou’-Loropetalum chinense ‘ZhuZhou’ Description: Evergreen; It has a loose, slightly open habit and a roughly rounded to vase- shaped form with a medium-fine texture. Height: 10-15 ft. Width: 10-15ft. Site: Preferred growing conditions include sun to partial shade (especially afternoon shade) and moist, well-drained, acidic soil with plenty of organic matter Japanese Ternstroemia - Ternstroemia gymnanthera Comment: Evergreen; Salt spray tolerant; often sold as Cleyera japonica; can be severely pruned. Form is upright oval to rounded; densely branched. Height: 8-10 ft. Width: 5-6 ft. -

Survey of the Taxonomic and Tissue Distribution of Microsomal Binding

Survey of the Taxonomic and Tissue Distribution of Microsomal Binding Sites for the Non-Host Selective Fungal Phytotoxin, Fusicoccin Christiane Meyer3, Kerstin Waldkötter3, Annegret Sprenger3, Uwe G. Schlösset, Markus Luther0, and Elmar W. Weiler3 a Lehrstuhl für Pflanzenphysiologie, Ruhr-Universität, D-44780 Bochum, Bundesrepublik Deutschland b Pflanzenphysiologisches Institut (SAG) der Universität, D-37073 Göttingen, Bundesrepublik Deutschland c KFA Jülich, D-52428 Jülich, Bundesrepublik Deutschland Z. Naturforsch. 48c, 595-602(1993); received June 4/July 13, 1993 Vicia faba L., Fusicoccin-Binding Sites. Taxonomie Distribution, Tissue Distribution, Guard Cell Protoplasts The recent identification of the fusicoccin-binding protein (FCBP) in plasma membranes from monocotyledonous and dicotyledonous angiosperms has opened the basis for an elucida tion of the toxin’s mechanism(s) of action and indicated a widespread occurrence of the FCBP in plants. Results of a detailed taxonomic survey of fusicoccin-binding sites are reported. Bind ing sites were not found in prokaryotes, animal tissues, fungi and algae including the most direct extant ancestors of the land plants (Coleochaete). From the Psilotales (Psilophytatae) to the monocotyledonous angiosperms, all taxa analyzed possessed high-affinity microsomal fusicoccin-binding sites. A heterogeneous picture emerged for the Bryophvta. Anthoceros cri- spulus (Anthocerotae), the only hornwort available to study, lacked fusicoccin binding. Within the Hepaticae as well as the Musci, species lacking and species exhibiting toxin binding were found. The binding site thus seems to have emerged very early in the evolution of the land plants. The tissue distribution of fusicoccin-binding sites was studied in Vicia faba L. shoots. All tissues analyzed showed fusicoccin binding, although not to the same extent. -

Department of Planning and Zoning

Department of Planning and Zoning Subject: Howard County Landscape Manual Updates: Recommended Street Tree List (Appendix B) and Recommended Plant List (Appendix C) - Effective July 1, 2010 To: DLD Review Staff Homebuilders Committee From: Kent Sheubrooks, Acting Chief Division of Land Development Date: July 1, 2010 Purpose: The purpose of this policy memorandum is to update the Recommended Plant Lists presently contained in the Landscape Manual. The plant lists were created for the first edition of the Manual in 1993 before information was available about invasive qualities of certain recommended plants contained in those lists (Norway Maple, Bradford Pear, etc.). Additionally, diseases and pests have made some other plants undesirable (Ash, Austrian Pine, etc.). The Howard County General Plan 2000 and subsequent environmental and community planning publications such as the Route 1 and Route 40 Manuals and the Green Neighborhood Design Guidelines have promoted the desirability of using native plants in landscape plantings. Therefore, this policy seeks to update the Recommended Plant Lists by identifying invasive plant species and disease or pest ridden plants for their removal and prohibition from further planting in Howard County and to add other available native plants which have desirable characteristics for street tree or general landscape use for inclusion on the Recommended Plant Lists. Please note that a comprehensive review of the street tree and landscape tree lists were conducted for the purpose of this update, however, only -

Central Appalachian Broadleaf Forest Coniferous Forest Meadow Province

Selecting Plants for Pollinators A Regional Guide for Farmers, Land Managers, and Gardeners In the Central Appalachian Broadleaf Forest Coniferous Forest Meadow Province Including the states of: Maryland, Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia And parts of: Georgia, Kentucky, and North Carolina, NAPPC South Carolina, Tennessee Table of CONTENTS Why Support Pollinators? 4 Getting Started 5 Central Appalachian Broadleaf Forest 6 Meet the Pollinators 8 Plant Traits 10 Developing Plantings 12 Far ms 13 Public Lands 14 Home Landscapes 15 Bloom Periods 16 Plants That Attract Pollinators 18 Habitat Hints 20 This is one of several guides for Check list 22 different regions in the United States. We welcome your feedback to assist us in making the future Resources and Feedback 23 guides useful. Please contact us at [email protected] Cover: silver spotted skipper courtesy www.dangphoto.net 2 Selecting Plants for Pollinators Selecting Plants for Pollinators A Regional Guide for Farmers, Land Managers, and Gardeners In the Ecological Region of the Central Appalachian Broadleaf Forest Coniferous Forest Meadow Province Including the states of: Maryland, Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia And parts of: Georgia, Kentucky, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee a nappc and Pollinator Partnership™ Publication This guide was funded by the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, the C.S. Fund, the Plant Conservation Alliance, the U.S. Forest Service, and the Bureau of Land Management with oversight by the Pollinator Partnership™ (www.pollinator.org), in support of the North American Pollinator Protection Campaign (NAPPC–www.nappc.org). Central Appalachian Broadleaf Forest – Coniferous Forest – Meadow Province 3 Why support pollinators? In theIr 1996 book, the Forgotten PollInators, Buchmann and Nabhan estimated that animal pollinators are needed for the reproduction “ Farming feeds of 90% of flowering plants and one third of human food crops. -

The Distribution and Habitat Selection of Introduced Eastern Grey Squirrels, Sciurus Carolinensis, in British Columbia

03_03045_Squirrels.qxd 11/7/06 4:25 PM Page 343 The Distribution and Habitat Selection of Introduced Eastern Grey Squirrels, Sciurus carolinensis, in British Columbia EMILY K. GONZALES Centre for Applied Conservation Research, University of British Columbia, Forest Sciences Centre, 3004-2424 Main Mall, Vancouver, British Columbia V6T 1Z4 Canada Gonzales, Emily K. 2005. The distribution and habitat selection of introduced Eastern Grey Squirrels, Sciurus carolinensis,in British Columbia. Canadian Field-Naturalist 119(3): 343-350. Eastern Grey Squirrels were first introduced to Vancouver in the Lower Mainland of British Columbia in 1909. A separate introduction to Metchosin in the Victoria region occurred in 1966. I surveyed the distribution and habitat selection of East- ern Grey Squirrels in both locales. Eastern Grey Squirrels spread throughout both regions over a period of 30 years and were found predominantly in residential land types. Some natural features and habitats, such as mountains, large bodies of water, and coniferous forests, have acted as barriers to expansion for Eastern Grey Squirrels. Given that urbanization is replacing conifer forests throughout southern British Columbia, it is predicted that Eastern Grey Squirrels will continue to spread as habitat barriers are removed. Key Words: Eastern Grey Squirrels, Sciurus carolinensis, distribution, habitat selection, invasive, British Columbia. The vast majority of introduced species do not suc- such as backyards, parks, and cemeteries (Pasitschniak- cessfully establish populations in novel environments Arts and Bendell 1990). EGS co-occur with North (Williamson 1996). Many successful non-native species American Red Squirrels (Tamiasciurus hudsonicus) are human comensals which thrive in human-modified throughout much of their range where habitat special- environments (Williamson and Fitter 1996; Sax and ization and not competition determines the differences Brown 2000). -

Carolina Hemlock Information

http://www.cnr.vt.edu/dendro/dendrology/syllabus/factsheet.cfm?ID=143 USDAFS Additional Silvics Index of Species Information SPECIES: Tsuga caroliniana Introductory Distribution and Occurrence Management Considerations Botanical and Ecological Characteristics Fire Ecology Fire Effects References Introductory SPECIES: Tsuga caroliniana AUTHORSHIP AND CITATION : Coladonato, Milo 1993. Tsuga caroliniana. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/ [2009, November 2]. ABBREVIATION : TSUCAR SYNONYMS : NO-ENTRY SCS PLANT CODE : TSCA2 COMMON NAMES : Carolina hemlock TAXONOMY : The currently accepted scientific name of Carolina hemlock is Tsuga caroliniana Engelm. [12]. There are no recognized subspecies, varieties, or forms. LIFE FORM : Tree FEDERAL LEGAL STATUS : No special status OTHER STATUS : Carolina hemlock is listed as rare in its natural range [11]. DISTRIBUTION AND OCCURRENCE SPECIES: Tsuga caroliniana GENERAL DISTRIBUTION : Carolina hemlock has a very limited distribution. It occurs along the slopes of the Appalachian Mountains from southwestern Virginia and western North Carolina into South Carolina and northern Georgia [6,8,22]. ECOSYSTEMS : FRES14 Oak - pine FRES15 Oak - hickory STATES : GA NC SC TN VA BLM PHYSIOGRAPHIC REGIONS : NO-ENTRY KUCHLER PLANT ASSOCIATIONS : K104 Appalachian oak forest K111 Oak - hickory - pine forest SAF COVER TYPES : 44 Chestnut oak 58 Yellow-poplar - eastern hemlock 59 Yellow-poplar - white oak - northern red oak 78 Virginia pine - oak 87 Sweet gum - yellow-poplar SRM (RANGELAND) COVER TYPES : NO-ENTRY HABITAT TYPES AND PLANT COMMUNITIES : NO-ENTRY MANAGEMENT CONSIDERATIONS SPECIES: Tsuga caroliniana WOOD PRODUCTS VALUE : The wood of Carolina hemlock can be used for lumber or pulpwood, but the species is so limited in extent that it is not considered commercially important [6,16]. -

Native Trees of Georgia

1 NATIVE TREES OF GEORGIA By G. Norman Bishop Professor of Forestry George Foster Peabody School of Forestry University of Georgia Currently Named Daniel B. Warnell School of Forest Resources University of Georgia GEORGIA FORESTRY COMMISSION Eleventh Printing - 2001 Revised Edition 2 FOREWARD This manual has been prepared in an effort to give to those interested in the trees of Georgia a means by which they may gain a more intimate knowledge of the tree species. Of about 250 species native to the state, only 92 are described here. These were chosen for their commercial importance, distribution over the state or because of some unusual characteristic. Since the manual is intended primarily for the use of the layman, technical terms have been omitted wherever possible; however, the scientific names of the trees and the families to which they belong, have been included. It might be explained that the species are grouped by families, the name of each occurring at the top of the page over the name of the first member of that family. Also, there is included in the text, a subdivision entitled KEY CHARACTERISTICS, the purpose of which is to give the reader, all in one group, the most outstanding features whereby he may more easily recognize the tree. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author wishes to express his appreciation to the Houghton Mifflin Company, publishers of Sargent’s Manual of the Trees of North America, for permission to use the cuts of all trees appearing in this manual; to B. R. Stogsdill for assistance in arranging the material; to W. -

Native Plants for Your Backyard

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Native Plants for Your Backyard Native plants of the Southeastern United States are more diverse in number and kind than in most other countries, prized for their beauty worldwide. Our native plants are an integral part of a healthy ecosystem, providing the energy that sustains our forests and wildlife, including important pollinators and migratory birds. By “growing native” you can help support native wildlife. This helps sustain the natural connections that have developed between plants and animals over thousands of years. Consider turning your lawn into a native garden. You’ll help the local environment and often use less water and spend less time and money maintaining your yard if the plants are properly planted. The plants listed are appealing to many species of wildlife and will look attractive in your yard. To maximize your success with these plants, match the right plants with the right site conditions (soil, pH, sun, and moisture). Check out the resources on the back of this factsheet for assistance or contact your local extension office for soil testing and more information about these plants. Shrubs Trees Vines Wildflowers Grasses American beautyberry Serviceberry Trumpet creeper Bee balm Big bluestem Callicarpa americana Amelanchier arborea Campsis radicans Monarda didyma Andropogon gerardii Sweetshrub Redbud Carolina jasmine Fire pink Little bluestem Calycanthus floridus Cercis canadensis Gelsemium sempervirens Silene virginica Schizachyrium scoparium Blueberry Red buckeye Crossvine Cardinal flower -

Hemlock Woolly Adelgid Fact Sheet

w Department of HEMLOCK WOOLLY ADELGID RK 4 ATE Environmental Adelges tsugae Conservation ▐ What is the hemlock woolly adelgid? The hemlock woolly adelgid, or HWA, is an invasive, aphid-like insect that attacks North American hemlocks. HWA are very small (1.5 mm) and often hard to see, but they can be easily identified by the white woolly masses they form on the underside of branches at the base of the needles. These masses or ovisacs can contain up to 200 eggs and remain present throughout the year. ▐ Where is HWA located? HWA was first discovered in New York State in 1985 in the lower White woolly ovisacs on an Hudson Valley and on Long Island. Since then, it has spread north to eastern hemlock branch Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station, the Capitol Region and west through the Catskill Mountains to the Bugwood.org Finger Lakes Region, Buffalo and Rochester. In 2017, the first known occurrence in the Adirondack Park was discovered in Lake George. Where does HWA come from? Native to Asia, HWA was introduced to the western United States in the 1920s. It was first observed in the eastern US in 1951 near Richmond, Virginia after an accidental introduction from Japan. HWA has since spread along the East Coast from Georgia to Maine and now occupies nearly half the eastern range of native hemlocks. ▐ What does HWA do to trees? Once hatched, juvenile HWA, known as crawlers, search for suitable sites on the host tree, usually at the base of the needles. They insert their long mouthparts and begin feeding on the tree’s stored starches. -

Natural Community Fact Sheet Coastal Forests, Maritime Forests, and Maritime Shrublands

Commonwealth of Massachusetts Natural Heritage Division of Fisheries & Wildlife Endangered Species Route 135 Westborough, MA 01581 Program www.nhesp.org (508) 792-7270 ext. 200/fax (508)792-7821 Natural Community Fact Sheet Coastal Forests, Maritime Forests, and Maritime Shrublands Community Descriptions Coastal and maritime communities occur very near the ocean. Coastal and maritime forests and maritime shrublands are within the northeastern oak and oak-pine forest, and are variants of those prevailing forest types. Species of these communities are species of the oak forest, including species with southern distributions, such as American holly (Ilex opaca) and tupelo (Nyssa sylvatica), the result of the more moderate temperatures along the coast. The coastal vegetation of the state includes a variety of fairly distinct, but repeated, plant groupings that can be classed separately as Maritime forest behind beach and salt marsh, with shrubs, Juniper and deciduous trees behind. distinct associations within the community T. Huguenin photo. types. The differences among the communities and associations are often gradual, making differentiation on the ground difficult at times. Northeast: Ammophla --------------,:1- Arctostoph y/OS Pinus rlgido Fogus Co/die Lothyrus Quercus i/icifolio ---------~ Qiercis veluhno ------------:1- Solidago spp. --------Ame/Qnchler Ouercus o/t:>o ----------~ Xon fh/um Vacclnlum co,ymbosum Voce. voci/lon, vocNlons Acerrut:>rum HuCJsonta---------------+Prunus serohno ----------... Sa ssafras Lechea Comptonia Mitche/lo Myrica pensy/von.:o Prunusmaritimo ----------------~ l?husfoxieodendron--------------- Chimphi/0 Porlhenocissus -----------------~ Rre island: flex opaco Ame1oncn;er Sassafras From Godfrey, 1976b, in Bellis, 1995. Ecology of Maritime Forests of the Southern Atlantic Coast: A Community Profile. USNBS. The heights of Coastal Forests are variable but often 10-20m (about 30 to 60 feet); not as tall as further inland, but taller than maritime forests. -

Native Nebraska Woody Plants

THE NEBRASKA STATEWIDE ARBORETUM PRESENTS NATIVE NEBRASKA WOODY PLANTS Trees (Genus/Species – Common Name) 62. Atriplex canescens - four-wing saltbrush 1. Acer glabrum - Rocky Mountain maple 63. Atriplex nuttallii - moundscale 2. Acer negundo - boxelder maple 64. Ceanothus americanus - New Jersey tea 3. Acer saccharinum - silver maple 65. Ceanothus herbaceous - inland ceanothus 4. Aesculus glabra - Ohio buckeye 66. Cephalanthus occidentalis - buttonbush 5. Asimina triloba - pawpaw 67. Cercocarpus montanus - mountain mahogany 6. Betula occidentalis - water birch 68. Chrysothamnus nauseosus - rabbitbrush 7. Betula papyrifera - paper birch 69. Chrysothamnus parryi - parry rabbitbrush 8. Carya cordiformis - bitternut hickory 70. Cornus amomum - silky (pale) dogwood 9. Carya ovata - shagbark hickory 71. Cornus drummondii - roughleaf dogwood 10. Celtis occidentalis - hackberry 72. Cornus racemosa - gray dogwood 11. Cercis canadensis - eastern redbud 73. Cornus sericea - red-stem (redosier) dogwood 12. Crataegus mollis - downy hawthorn 74. Corylus americana - American hazelnut 13. Crataegus succulenta - succulent hawthorn 75. Euonymus atropurpureus - eastern wahoo 14. Fraxinus americana - white ash 76. Juniperus communis - common juniper 15. Fraxinus pennsylvanica - green ash 77. Juniperus horizontalis - creeping juniper 16. Gleditsia triacanthos - honeylocust 78. Mahonia repens - creeping mahonia 17. Gymnocladus dioicus - Kentucky coffeetree 79. Physocarpus opulifolius - ninebark 18. Juglans nigra - black walnut 80. Prunus besseyi - western sandcherry 19. Juniperus scopulorum - Rocky Mountain juniper 81. Rhamnus lanceolata - lanceleaf buckthorn 20. Juniperus virginiana - eastern redcedar 82. Rhus aromatica - fragrant sumac 21. Malus ioensis - wild crabapple 83. Rhus copallina - flameleaf (shining) sumac 22. Morus rubra - red mulberry 84. Rhus glabra - smooth sumac 23. Ostrya virginiana - hophornbeam (ironwood) 85. Rhus trilobata - skunkbush sumac 24. Pinus flexilis - limber pine 86. Ribes americanum - wild black currant 25. -

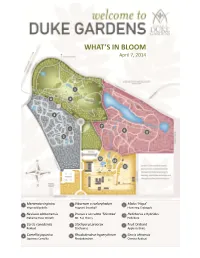

What's in Bloom

WHAT’S IN BLOOM April 7, 2014 5 4 6 2 7 1 9 8 3 12 10 11 1 Mertensia virginica 5 Viburnum x carlcephalum 9 Malus ‘Hopa’ Virginia Bluebells Fragrant Snowball Flowering Crabapple 2 Neviusia alabamensis 6 Prunus x serrulata ‘Shirotae’ 10 Helleborus x hybridus Alabama Snow Wreath Mt. Fuji Cherry Hellebore 3 Cercis canadensis 7 Stachyurus praecox 11 Fruit Orchard Redbud Stachyurus Apple cultivars 4 Camellia japonica 8 Rhododendron hyperythrum 12 Cercis chinensis Japanese Camellia Rhododendron Chinese Redbud WHAT’S IN BLOOM April 7, 2014 BLOMQUIST GARDEN OF NATIVE PLANTS Amelanchier arborea Common Serviceberry Sanguinaria canadensis Bloodroot Cornus florida Flowering Dogwood Stylophorum diphyllum Celandine Poppy Thalictrum thalictroides Rue Anemone Fothergilla major Fothergilla Trillium decipiens Chattahoochee River Trillium Hepatica nobilis Hepatica Trillium grandiflorum White Trillium Hexastylis virginica Wild Ginger Hexastylis minor Wild Ginger Trillium pusillum Dwarf Wakerobin Illicium floridanum Florida Anise Tree Trillium stamineum Blue Ridge Wakerobin Malus coronaria Sweet Crabapple Uvularia sessilifolia Sessileleaf Bellwort Mertensia virginica Virginia Bluebells Pachysandra procumbens Allegheny spurge Prunus americana American Plum DORIS DUKE CENTER GARDENS Camellia japonica Japanese Camellia Pulmonaria ‘Diana Clare’ Lungwort Cercis canadensis Redbud Prunus persica Flowering Peach Puschkinia scilloides Striped Squill Cercis chinensis Redbud Sanguinaria canadensis Bloodroot Clematis armandii Evergreen Clematis Spiraea prunifolia Bridalwreath