2005 Forest Ecosystem Study Unit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Department of Planning and Zoning

Department of Planning and Zoning Subject: Howard County Landscape Manual Updates: Recommended Street Tree List (Appendix B) and Recommended Plant List (Appendix C) - Effective July 1, 2010 To: DLD Review Staff Homebuilders Committee From: Kent Sheubrooks, Acting Chief Division of Land Development Date: July 1, 2010 Purpose: The purpose of this policy memorandum is to update the Recommended Plant Lists presently contained in the Landscape Manual. The plant lists were created for the first edition of the Manual in 1993 before information was available about invasive qualities of certain recommended plants contained in those lists (Norway Maple, Bradford Pear, etc.). Additionally, diseases and pests have made some other plants undesirable (Ash, Austrian Pine, etc.). The Howard County General Plan 2000 and subsequent environmental and community planning publications such as the Route 1 and Route 40 Manuals and the Green Neighborhood Design Guidelines have promoted the desirability of using native plants in landscape plantings. Therefore, this policy seeks to update the Recommended Plant Lists by identifying invasive plant species and disease or pest ridden plants for their removal and prohibition from further planting in Howard County and to add other available native plants which have desirable characteristics for street tree or general landscape use for inclusion on the Recommended Plant Lists. Please note that a comprehensive review of the street tree and landscape tree lists were conducted for the purpose of this update, however, only -

Native Trees of Georgia

1 NATIVE TREES OF GEORGIA By G. Norman Bishop Professor of Forestry George Foster Peabody School of Forestry University of Georgia Currently Named Daniel B. Warnell School of Forest Resources University of Georgia GEORGIA FORESTRY COMMISSION Eleventh Printing - 2001 Revised Edition 2 FOREWARD This manual has been prepared in an effort to give to those interested in the trees of Georgia a means by which they may gain a more intimate knowledge of the tree species. Of about 250 species native to the state, only 92 are described here. These were chosen for their commercial importance, distribution over the state or because of some unusual characteristic. Since the manual is intended primarily for the use of the layman, technical terms have been omitted wherever possible; however, the scientific names of the trees and the families to which they belong, have been included. It might be explained that the species are grouped by families, the name of each occurring at the top of the page over the name of the first member of that family. Also, there is included in the text, a subdivision entitled KEY CHARACTERISTICS, the purpose of which is to give the reader, all in one group, the most outstanding features whereby he may more easily recognize the tree. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author wishes to express his appreciation to the Houghton Mifflin Company, publishers of Sargent’s Manual of the Trees of North America, for permission to use the cuts of all trees appearing in this manual; to B. R. Stogsdill for assistance in arranging the material; to W. -

Fire and Nonnative Invasive Plants September 2008 Zouhar, Kristin; Smith, Jane Kapler; Sutherland, Steve; Brooks, Matthew L

United States Department of Agriculture Wildland Fire in Forest Service Rocky Mountain Research Station Ecosystems General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-42- volume 6 Fire and Nonnative Invasive Plants September 2008 Zouhar, Kristin; Smith, Jane Kapler; Sutherland, Steve; Brooks, Matthew L. 2008. Wildland fire in ecosystems: fire and nonnative invasive plants. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-42-vol. 6. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 355 p. Abstract—This state-of-knowledge review of information on relationships between wildland fire and nonnative invasive plants can assist fire managers and other land managers concerned with prevention, detection, and eradi- cation or control of nonnative invasive plants. The 16 chapters in this volume synthesize ecological and botanical principles regarding relationships between wildland fire and nonnative invasive plants, identify the nonnative invasive species currently of greatest concern in major bioregions of the United States, and describe emerging fire-invasive issues in each bioregion and throughout the nation. This volume can help increase understanding of plant invasions and fire and can be used in fire management and ecosystem-based management planning. The volume’s first part summarizes fundamental concepts regarding fire effects on invasions by nonnative plants, effects of plant invasions on fuels and fire regimes, and use of fire to control plant invasions. The second part identifies the nonnative invasive species of greatest concern and synthesizes information on the three topics covered in part one for nonnative inva- sives in seven major bioregions of the United States: Northeast, Southeast, Central, Interior West, Southwest Coastal, Northwest Coastal (including Alaska), and Hawaiian Islands. -

Potential Vegetation, Disturbance, Plant Succession, and Other Aspects of Forest Ecology

United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Potential Vegetation, Disturbance, Pacific Northwest Plant Succession, and Other Aspects of Region Umatilla National Forest Ecology Forest F14-SO-TP-09-00 May 2000 David C. Powell The Forest Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture is dedicated to the principle of multiple use management of the Nation’s forest resources for sustained yields of wood, water, forage, wildlife, and recreation. Through forestry research, cooperation with the States and private forest owners, and man- agement of the national forests and national grasslands, it strives – as directed by Congress – to provide increasingly greater service to a growing nation. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orienta- tion, and marital or family status. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabili- ties who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audio- tape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at 202-720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326-W, Whitten Building, 14th and Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call (202) 720- 5964 (voice or TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. ii Potential Vegetation, Disturbance, Plant Succession, and Other Aspects of Forest Ecology David C. Powell U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service Pacific Northwest Region Umatilla National Forest 2517 SW Hailey Avenue Pendleton, OR 97801 Technical Publication F14-SO-TP-09-00 May 2000 iii AUTHOR DAVID C. -

Stand Structure and Species Diversity Regulate Biomass Carbon Stock Under Major Central Himalayan Forest Types of India Siddhartha Kaushal and Ratul Baishya*

Kaushal and Baishya Ecological Processes (2021) 10:14 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13717-021-00283-8 RESEARCH Open Access Stand structure and species diversity regulate biomass carbon stock under major Central Himalayan forest types of India Siddhartha Kaushal and Ratul Baishya* Abstract Background: Data on the impact of species diversity on biomass in the Central Himalayas, along with stand structural attributes is sparse and inconsistent. Moreover, few studies in the region have related population structure and the influence of large trees on biomass. Such data is crucial for maintaining Himalayan biodiversity and carbon stock. Therefore, we investigated these relationships in major Central Himalayan forest types using non- destructive methodologies to determine key factors and underlying mechanisms. Results: Tropical Shorea robusta dominant forest has the highest total biomass density (1280.79 Mg ha−1) and total carbon density (577.77 Mg C ha−1) along with the highest total species richness (21 species). The stem density ranged between 153 and 457 trees ha−1 with large trees (> 70 cm diameter) contributing 0–22%. Conifer dominant forest types had higher median diameter and Cedrus deodara forest had the highest growing stock (718.87 m3 ha−1); furthermore, C. deodara contributed maximally toward total carbon density (14.6%) among all the 53 species combined. Quercus semecarpifolia–Rhododendron arboreum association forest had the highest total basal area (94.75 m2 ha−1). We found large trees to contribute up to 65% of the growing stock. Nine percent of the species contributed more than 50% of the carbon stock. Species dominance regulated the growing stock significantly (R2 = 0.707, p < 0.001). -

Quercus Coccinea.Indd

Quercus coccinea (Scarlet Oak) Beech Family (Fagaceae) Introduction: Scarlet oak is a member of the red oak group with lobed leaves and is valued for its ornamental attributes as well as its fi ne wood. It is considered an excellent alternative to the overplanted pin oak because it is beautiful throughout the year and tolerates alkaline soil. Culture: Scarlet oak makes an excellent lawn or park tree. It thrives in full sun and well-drained, acidic soil. This tree is less susceptible to chlorosis problems than pin oak. Potential problems on oaks in general include obscure scale, two-lined chestnut borer, bacterial leaf scorch, oak horn gall and gypsy moth. In addition, as little as 1 inch of fi ll soil can kill an oak. Botanical Characteristics: Additional information: Scarlet oak is appropriately named for its Native habit: Maine south to Florida, west to extraordinary leaf color in early spring and in autumn. Minnesota and Missouri. Its delicate branching pattern combined with nearly black bark and persistent leaves make this an exceptional tree Growth habit: Scarlet oak has a rounded, open even in winter. form at maturity. Although scarlet oak has a predominant tap root, it does have some spreading lateral roots, making the tree Tree size: This oak can attain a height of 70 to easier to transplant than some oaks. It is best to transplant 75 feet and a width of 40 to 50 feet. It can reach a the tree in the fall. The lateral roots may appear above the height of 100 feet in the wild. -

Introduction to the Southern Blue Ridge Ecoregional Conservation Plan

SOUTHERN BLUE RIDGE ECOREGIONAL CONSERVATION PLAN Summary and Implementation Document March 2000 THE NATURE CONSERVANCY and the SOUTHERN APPALACHIAN FOREST COALITION Southern Blue Ridge Ecoregional Conservation Plan Summary and Implementation Document Citation: The Nature Conservancy and Southern Appalachian Forest Coalition. 2000. Southern Blue Ridge Ecoregional Conservation Plan: Summary and Implementation Document. The Nature Conservancy: Durham, North Carolina. This document was produced in partnership by the following three conservation organizations: The Nature Conservancy is a nonprofit conservation organization with the mission to preserve plants, animals and natural communities that represent the diversity of life on Earth by protecting the lands and waters they need to survive. The Southern Appalachian Forest Coalition is a nonprofit organization that works to preserve, protect, and pass on the irreplaceable heritage of the region’s National Forests and mountain landscapes. The Association for Biodiversity Information is an organization dedicated to providing information for protecting the diversity of life on Earth. ABI is an independent nonprofit organization created in collaboration with the Network of Natural Heritage Programs and Conservation Data Centers and The Nature Conservancy, and is a leading source of reliable information on species and ecosystems for use in conservation and land use planning. Photocredits: Robert D. Sutter, The Nature Conservancy EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This first iteration of an ecoregional plan for the Southern Blue Ridge is a compendium of hypotheses on how to conserve species nearest extinction, rare and common natural communities and the rich and diverse biodiversity in the ecoregion. The plan identifies a portfolio of sites that is a vision for conservation action, enabling practitioners to set priorities among sites and develop site-specific and multi-site conservation strategies. -

Is Ecological Succession Predictable?

Is ecological succession predictable? Commissioned by Prof. dr. P. Opdam; Kennisbasis Thema 1. Project Ecosystem Predictability, Projectnr. 232317. 2 Alterra-Report 1277 Is ecological succession predictable? Theory and applications Koen Kramer Bert Brinkman Loek Kuiters Piet Verdonschot Alterra-Report 1277 Alterra, Wageningen, 2005 ABSTRACT Koen Kramer, Bert Brinkman, Loek Kuiters, Piet Verdonschot, 2005. Is ecological succession predictable? Theory and applications. Wageningen, Alterra, Alterra-Report 1277. 80 blz.; 6 figs.; 0 tables.; 197 refs. A literature study is presented on the predictability of ecological succession. Both equilibrium and nonequilibrium theories are discussed in relation to competition between, and co-existence of species. The consequences for conservation management are outlined and a research agenda is proposed focusing on a nonequilibrium view of ecosystem functioning. Applications are presented for freshwater-; marine-; dune- and forest ecosystems. Keywords: conservation management; competition; species co-existence; disturbance; ecological succession; equilibrium; nonequilibrium ISSN 1566-7197 This report can be ordered by paying € 15,- to bank account number 36 70 54 612 by name of Alterra Wageningen, IBAN number NL 83 RABO 036 70 54 612, Swift number RABO2u nl. Please refer to Alterra-Report 1277. This amount is including tax (where applicable) and handling costs. © 2005 Alterra P.O. Box 47; 6700 AA Wageningen; The Netherlands Phone: + 31 317 474700; fax: +31 317 419000; e-mail: [email protected] No part of this publication may be reproduced or published in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system without the written permission of Alterra. Alterra assumes no liability for any losses resulting from the use of the research results or recommendations in this report. -

Disturbance and Mosquito Diversity in the Lowland Tropical Rainforest of Central Panama Received: 28 October 2016 Jose R

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Disturbance and mosquito diversity in the lowland tropical rainforest of central Panama Received: 28 October 2016 Jose R. Loaiza1,2,3, Larissa C. Dutari1, Jose R. Rovira1,2, Oris I. Sanjur2, Gabriel Z. Laporta 4,5, Accepted: 28 June 2017 James Pecor6, Desmond H. Foley6, Gillian Eastwood7, Laura D. Kramer7, Meghan Radtke8 & Published: xx xx xxxx Montira Pongsiri8 The Intermediate Disturbance Hypothesis (IDH) is well-known in ecology providing an explanation for the role of disturbance in the coexistence of climax and colonist species. Here, we used the IDH as a framework to describe the role of forest disturbance in shaping the mosquito community structure, and to identify the ecological processes that increase the emergence of vector-borne disease. Mosquitoes were collected in central Panama at immature stages along linear transects in colonising, mixed and climax forest habitats, representing diferent levels of disturbance. Species were identifed taxonomically and classifed into functional categories (i.e., colonist, climax, disturbance-generalist, and rare). Using the Huisman-Olf-Fresco multi-model selection approach, IDH testing was done. We did not detect a unimodal relationship between species diversity and forest disturbance expected under the IDH; instead diversity peaked in old-growth forests. Habitat complexity and constraints are two mechanisms proposed to explain this alternative postulate. Moreover, colonist mosquito species were more likely to be involved in or capable of pathogen transmission than climax species. Vector species occurrence decreased notably in undisturbed forest settings. Old-growth forest conservation in tropical rainforests is therefore a highly-recommended solution for preventing new outbreaks of arboviral and parasitic diseases in anthropic environments. -

Ecological Zones in the Southern Appalachians: First Approximation

United States Department of Ecological Zones in the Southern Agriculture Forest Service Appalachians: First Approximation Steve A. Simon, Thomas K. Collins, Southern Gary L. Kauffman, W. Henry McNab, and Research Station Christopher J. Ulrey Research Paper SRS–41 The Authors Steven A. Simon, Ecologist, USDA Forest Service, National Forests in North Carolina, Asheville, NC 28802; Thomas K. Collins, Geologist, USDA Forest Service, George Washington and Jefferson National Forests, Roanoke, VA 24019; Gary L. Kauffman, Botanist, USDA Forest Service, National Forests in North Carolina, Asheville, NC 28802; W. Henry McNab, Research Forester, USDA Forest Service, Southern Research Station, Asheville, NC 28806; and Christopher J. Ulrey, Vegetation Specialist, U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Blue Ridge Parkway, Asheville, NC 28805. Cover Photos Ecological zones, regions of similar physical conditions and biological potential, are numerous and varied in the Southern Appalachian Mountains and are often typified by plant associations like the red spruce, Fraser fir, and northern hardwoods association found on the slopes of Mt. Mitchell (upper photo) and characteristic of high-elevation ecosystems in the region. Sites within ecological zones may be characterized by geologic formation, landform, aspect, and other physical variables that combine to form environments of varying temperature, moisture, and fertility, which are suitable to support characteristic species and forests, such as this Blue Ridge Parkway forest dominated by chestnut oak and pitch pine with an evergreen understory of mountain laurel (lower photo). DISCLAIMER The use of trade or firm names in this publication is for reader information and does not imply endorsement of any product or service by the U.S. -

Native Plant List Trees.XLS

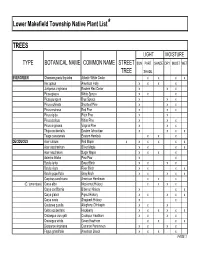

Lower Makefield Township Native Plant List* TREES LIGHT MOISTURE TYPE BOTANICAL NAME COMMON NAME STREET SUN PART SHADE DRY MOIST WET TREE SHADE EVERGREEN Chamaecyparis thyoides Atlantic White Cedar x x x x IIex opaca American Holly x x x x Juniperus virginiana Eastern Red Cedar x x x Picea glauca White Spruce x x x Picea pungens Blue Spruce x x x Pinus echinata Shortleaf Pine x x x Pinus resinosa Red Pine x x x Pinus rigida Pitch Pine x x Pinus strobus White Pine x x x Pinus virginiana Virginia Pine x x x Thuja occidentalis Eastern Arborvitae x x x x Tsuga canadensis Eastern Hemlock xx x DECIDUOUS Acer rubrum Red Maple x x x x x x Acer saccharinum Silver Maple x x x x Acer saccharum Sugar Maple x x x x Asimina triloba Paw-Paw x x Betula lenta Sweet Birch x x x x Betula nigra River Birch x x x x Betula populifolia Gray Birch x x x x x Carpinus caroliniana American Hornbeam x x x (C. tomentosa) Carya alba Mockernut Hickory x x x x Carya cordiformis Bitternut Hickory x x x Carya glabra Pignut Hickory x x x x x Carya ovata Shagbark Hickory x x Castanea pumila Allegheny Chinkapin xx x Celtis occidentalis Hackberry x x x x x x Crataegus crus-galli Cockspur Hawthorn x x x x Crataegus viridis Green Hawthorn x x x x Diospyros virginiana Common Persimmon x x x x Fagus grandifolia American Beech x x x x PAGE 1 Exhibit 1 TREES (cont'd) LIGHT MOISTURE TYPE BOTANICAL NAME COMMON NAME STREET SUN PART SHADE DRY MOIST WET TREE SHADE DECIDUOUS (cont'd) Fraxinus americana White Ash x x x x Fraxinus pennsylvanica Green Ash x x x x x Gleditsia triacanthos v. -

Old Growth Forest & Hetzel Nature Trail Guide

Old Growth Forest & Hetzel Nature Trail Rare. Distinctive. Diverse. 25 Acres of forest evolved over 10,000 years 59 63 47 51 56 34 46 26 1 2 17 Scenic. Historic. Dynamic. North Trail (1.4 miles) South Trail (.9 mile) Centerville Creek Trail Entrances Please respect LTC’s Old Growth Forest • Stay on the hiking trail. • No pets or bikes. • Clean the soles of your shoes to avoid introducing seeds of exotic (non-native) species. • Collecting is not allowed. • Leave no trace. Lakeshore Technical College has a unique ecological asset in its 25-acre forest – a wooded area containing old-growth trees. This is a unique biological feature that has evolved for more than 10,000 years without any recent significant intervention. This rare and distinctive treasure located on LTC’s campus will serve as the base for an educational trail. The preservation of the forest, construction of the trail, and this trail guide are the result of a volunteer partnership of concerned community members, with officials from Woodland Dunes Nature Center, UW-Manitowoc, UW-Sheboygan and LTC. LTC lies just northeast of the “Tension Zone” that separated Wisconsin’s two distinct floristic provinces at the time of European exploration: the southern hardwood forest, oak savanna, and prairie province to the south, and the conifer and northern hardwood forest to the north. The tension zone boasts an intermingling of species from both provinces. This forest is close enough to the tension zone to be considered a part of it since it has both the northern and southern components. See page 11.