Hill's Oak: the Taxonomy and Dynamics of a Western Great Lakes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Department of Planning and Zoning

Department of Planning and Zoning Subject: Howard County Landscape Manual Updates: Recommended Street Tree List (Appendix B) and Recommended Plant List (Appendix C) - Effective July 1, 2010 To: DLD Review Staff Homebuilders Committee From: Kent Sheubrooks, Acting Chief Division of Land Development Date: July 1, 2010 Purpose: The purpose of this policy memorandum is to update the Recommended Plant Lists presently contained in the Landscape Manual. The plant lists were created for the first edition of the Manual in 1993 before information was available about invasive qualities of certain recommended plants contained in those lists (Norway Maple, Bradford Pear, etc.). Additionally, diseases and pests have made some other plants undesirable (Ash, Austrian Pine, etc.). The Howard County General Plan 2000 and subsequent environmental and community planning publications such as the Route 1 and Route 40 Manuals and the Green Neighborhood Design Guidelines have promoted the desirability of using native plants in landscape plantings. Therefore, this policy seeks to update the Recommended Plant Lists by identifying invasive plant species and disease or pest ridden plants for their removal and prohibition from further planting in Howard County and to add other available native plants which have desirable characteristics for street tree or general landscape use for inclusion on the Recommended Plant Lists. Please note that a comprehensive review of the street tree and landscape tree lists were conducted for the purpose of this update, however, only -

Morphometric Leaf Variation in Oaks (Quercus) of Bolu, Turkey

Ann. Bot. Fennici 40: 233–242 ISSN 0003-3847 Helsinki 29 August 2003 © Finnish Zoological and Botanical Publishing Board 2003 Morphometric leaf variation in oaks (Quercus) of Bolu, Turkey Aydın Borazan & Mehmet T. Babaç Department of Biology, Abant |zzet Baysal University, Gölköy 14280 Bolu, Turkey (e-mail: [email protected], [email protected]) Received 16 Sep. 2002, revised version received 7 Jan. 2003, accepted 10 Jan. 2003 Borazan, A. & Babaç, M. T. 2003: Morphometric leaf variation in oaks (Quercus) of Bolu, Turkey. — Ann. Bot. Fennici 40: 233–242. Genus Quercus (Fagaceae) has a problematic taxonomy because of widespread hybridization between the infrageneric taxa. The pattern of morphological leaf varia- tion was evaluated for evidence of hybridization in Bolu, Turkey, since previous stud- ies suggested that in oaks leaf morphology is a good indicator of putative hybridiza- tion. Principal components analysis was applied to data sets of leaf characters from fi ve populations to describe variation in leaf morphology. Leaf characters analyzed in this study showed high degrees of variation as a result of hybridization between four taxa (Q. pubescens, Q. virgiliana, Q. petraea and Q. robur) of subgenus Quercus while Q. cerris as a member of subgenus Cerris was clearly separated from the others. Key words: hybridization, morphological leaf variation, principal components analy- sis, Quercus Introduction in regions of mild and warm temperate climates. Fossil leaves indicate that todayʼs several major In the northern hemisphere oaks (Quercus) are oak groups are at least 40 million years old. Gen- conspicuous members of the temperate decidu- eral distribution of fossil ancestors supports the ous, broad leaved forests. -

Native Trees of Georgia

1 NATIVE TREES OF GEORGIA By G. Norman Bishop Professor of Forestry George Foster Peabody School of Forestry University of Georgia Currently Named Daniel B. Warnell School of Forest Resources University of Georgia GEORGIA FORESTRY COMMISSION Eleventh Printing - 2001 Revised Edition 2 FOREWARD This manual has been prepared in an effort to give to those interested in the trees of Georgia a means by which they may gain a more intimate knowledge of the tree species. Of about 250 species native to the state, only 92 are described here. These were chosen for their commercial importance, distribution over the state or because of some unusual characteristic. Since the manual is intended primarily for the use of the layman, technical terms have been omitted wherever possible; however, the scientific names of the trees and the families to which they belong, have been included. It might be explained that the species are grouped by families, the name of each occurring at the top of the page over the name of the first member of that family. Also, there is included in the text, a subdivision entitled KEY CHARACTERISTICS, the purpose of which is to give the reader, all in one group, the most outstanding features whereby he may more easily recognize the tree. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author wishes to express his appreciation to the Houghton Mifflin Company, publishers of Sargent’s Manual of the Trees of North America, for permission to use the cuts of all trees appearing in this manual; to B. R. Stogsdill for assistance in arranging the material; to W. -

A Systems Biology Approach for Identifying Candidate Genes

A systems biology approach for identifying candidate genes involved in the natural variability of biomass yield and chemical properties in black poplar Vincent Segura, Marie-Claude Lesage Descauses, Jean-Paul Charpentier, Kévin Kinkel, Claire Mandin, Kévin Ader, Nassim Belmokhtar, Nathalie Boizot, Corinne Buret, Annabelle Dejardin, et al. To cite this version: Vincent Segura, Marie-Claude Lesage Descauses, Jean-Paul Charpentier, Kévin Kinkel, Claire Mandin, et al.. A systems biology approach for identifying candidate genes involved in the natural variability of biomass yield and chemical properties in black poplar. IUFRO Genomics and Forest Tree Genetics, May 2016, Arcachon, France. 2016, IUFRO Genomics and Forest Tree Genetics. Book of Abstract. hal-01456004 HAL Id: hal-01456004 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01456004 Submitted on 3 Jun 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Abstract Book 1 Table of Contents Welcome……………………………………………………………………………………3 Presentation Abstracts……………………………………………………………………4 Opening Keynote Lecture………………………………………………………………...4 -

Quercus Coccinea.Indd

Quercus coccinea (Scarlet Oak) Beech Family (Fagaceae) Introduction: Scarlet oak is a member of the red oak group with lobed leaves and is valued for its ornamental attributes as well as its fi ne wood. It is considered an excellent alternative to the overplanted pin oak because it is beautiful throughout the year and tolerates alkaline soil. Culture: Scarlet oak makes an excellent lawn or park tree. It thrives in full sun and well-drained, acidic soil. This tree is less susceptible to chlorosis problems than pin oak. Potential problems on oaks in general include obscure scale, two-lined chestnut borer, bacterial leaf scorch, oak horn gall and gypsy moth. In addition, as little as 1 inch of fi ll soil can kill an oak. Botanical Characteristics: Additional information: Scarlet oak is appropriately named for its Native habit: Maine south to Florida, west to extraordinary leaf color in early spring and in autumn. Minnesota and Missouri. Its delicate branching pattern combined with nearly black bark and persistent leaves make this an exceptional tree Growth habit: Scarlet oak has a rounded, open even in winter. form at maturity. Although scarlet oak has a predominant tap root, it does have some spreading lateral roots, making the tree Tree size: This oak can attain a height of 70 to easier to transplant than some oaks. It is best to transplant 75 feet and a width of 40 to 50 feet. It can reach a the tree in the fall. The lateral roots may appear above the height of 100 feet in the wild. -

Introduction to the Southern Blue Ridge Ecoregional Conservation Plan

SOUTHERN BLUE RIDGE ECOREGIONAL CONSERVATION PLAN Summary and Implementation Document March 2000 THE NATURE CONSERVANCY and the SOUTHERN APPALACHIAN FOREST COALITION Southern Blue Ridge Ecoregional Conservation Plan Summary and Implementation Document Citation: The Nature Conservancy and Southern Appalachian Forest Coalition. 2000. Southern Blue Ridge Ecoregional Conservation Plan: Summary and Implementation Document. The Nature Conservancy: Durham, North Carolina. This document was produced in partnership by the following three conservation organizations: The Nature Conservancy is a nonprofit conservation organization with the mission to preserve plants, animals and natural communities that represent the diversity of life on Earth by protecting the lands and waters they need to survive. The Southern Appalachian Forest Coalition is a nonprofit organization that works to preserve, protect, and pass on the irreplaceable heritage of the region’s National Forests and mountain landscapes. The Association for Biodiversity Information is an organization dedicated to providing information for protecting the diversity of life on Earth. ABI is an independent nonprofit organization created in collaboration with the Network of Natural Heritage Programs and Conservation Data Centers and The Nature Conservancy, and is a leading source of reliable information on species and ecosystems for use in conservation and land use planning. Photocredits: Robert D. Sutter, The Nature Conservancy EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This first iteration of an ecoregional plan for the Southern Blue Ridge is a compendium of hypotheses on how to conserve species nearest extinction, rare and common natural communities and the rich and diverse biodiversity in the ecoregion. The plan identifies a portfolio of sites that is a vision for conservation action, enabling practitioners to set priorities among sites and develop site-specific and multi-site conservation strategies. -

2005 Forest Ecosystem Study Unit

TABLE OF CONTENTS Forest Ecosystems............................................................................................................... 1 What is an ecosystem?.................................................................................................... 2 Ecosystem Classification ................................................................................................ 2 What is a forest?.............................................................................................................. 5 What are the different kinds of forests?.......................................................................... 5 Why do we need forests? ................................................................................................ 6 What are the layers of a forest?....................................................................................... 8 Ecological Succession......................................................................................................... 9 How Forest Ecosystems Change..................................................................................... 9 Stages of Succession..................................................................................................... 10 How Succession Affects Energy Flow ......................................................................... 12 Species Characteristic of Georgia’s Ecosystems .......................................................... 13 Tree Identification........................................................................................................ -

And Natural Community Restoration

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR LANDSCAPING AND NATURAL COMMUNITY RESTORATION Natural Heritage Conservation Program Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources P.O. Box 7921, Madison, WI 53707 August 2016, PUB-NH-936 Visit us online at dnr.wi.gov search “ER” Table of Contents Title ..……………………………………………………….……......………..… 1 Southern Forests on Dry Soils ...................................................... 22 - 24 Table of Contents ...……………………………………….….....………...….. 2 Core Species .............................................................................. 22 Background and How to Use the Plant Lists ………….……..………….….. 3 Satellite Species ......................................................................... 23 Plant List and Natural Community Descriptions .…………...…………….... 4 Shrub and Additional Satellite Species ....................................... 24 Glossary ..................................................................................................... 5 Tree Species ............................................................................... 24 Key to Symbols, Soil Texture and Moisture Figures .................................. 6 Northern Forests on Rich Soils ..................................................... 25 - 27 Prairies on Rich Soils ………………………………….…..….……....... 7 - 9 Core Species .............................................................................. 25 Core Species ...……………………………….…..…….………........ 7 Satellite Species ......................................................................... 26 Satellite Species -

Ecological Zones in the Southern Appalachians: First Approximation

United States Department of Ecological Zones in the Southern Agriculture Forest Service Appalachians: First Approximation Steve A. Simon, Thomas K. Collins, Southern Gary L. Kauffman, W. Henry McNab, and Research Station Christopher J. Ulrey Research Paper SRS–41 The Authors Steven A. Simon, Ecologist, USDA Forest Service, National Forests in North Carolina, Asheville, NC 28802; Thomas K. Collins, Geologist, USDA Forest Service, George Washington and Jefferson National Forests, Roanoke, VA 24019; Gary L. Kauffman, Botanist, USDA Forest Service, National Forests in North Carolina, Asheville, NC 28802; W. Henry McNab, Research Forester, USDA Forest Service, Southern Research Station, Asheville, NC 28806; and Christopher J. Ulrey, Vegetation Specialist, U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Blue Ridge Parkway, Asheville, NC 28805. Cover Photos Ecological zones, regions of similar physical conditions and biological potential, are numerous and varied in the Southern Appalachian Mountains and are often typified by plant associations like the red spruce, Fraser fir, and northern hardwoods association found on the slopes of Mt. Mitchell (upper photo) and characteristic of high-elevation ecosystems in the region. Sites within ecological zones may be characterized by geologic formation, landform, aspect, and other physical variables that combine to form environments of varying temperature, moisture, and fertility, which are suitable to support characteristic species and forests, such as this Blue Ridge Parkway forest dominated by chestnut oak and pitch pine with an evergreen understory of mountain laurel (lower photo). DISCLAIMER The use of trade or firm names in this publication is for reader information and does not imply endorsement of any product or service by the U.S. -

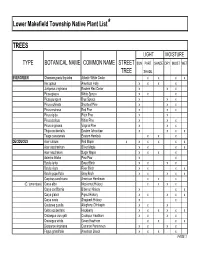

Native Plant List Trees.XLS

Lower Makefield Township Native Plant List* TREES LIGHT MOISTURE TYPE BOTANICAL NAME COMMON NAME STREET SUN PART SHADE DRY MOIST WET TREE SHADE EVERGREEN Chamaecyparis thyoides Atlantic White Cedar x x x x IIex opaca American Holly x x x x Juniperus virginiana Eastern Red Cedar x x x Picea glauca White Spruce x x x Picea pungens Blue Spruce x x x Pinus echinata Shortleaf Pine x x x Pinus resinosa Red Pine x x x Pinus rigida Pitch Pine x x Pinus strobus White Pine x x x Pinus virginiana Virginia Pine x x x Thuja occidentalis Eastern Arborvitae x x x x Tsuga canadensis Eastern Hemlock xx x DECIDUOUS Acer rubrum Red Maple x x x x x x Acer saccharinum Silver Maple x x x x Acer saccharum Sugar Maple x x x x Asimina triloba Paw-Paw x x Betula lenta Sweet Birch x x x x Betula nigra River Birch x x x x Betula populifolia Gray Birch x x x x x Carpinus caroliniana American Hornbeam x x x (C. tomentosa) Carya alba Mockernut Hickory x x x x Carya cordiformis Bitternut Hickory x x x Carya glabra Pignut Hickory x x x x x Carya ovata Shagbark Hickory x x Castanea pumila Allegheny Chinkapin xx x Celtis occidentalis Hackberry x x x x x x Crataegus crus-galli Cockspur Hawthorn x x x x Crataegus viridis Green Hawthorn x x x x Diospyros virginiana Common Persimmon x x x x Fagus grandifolia American Beech x x x x PAGE 1 Exhibit 1 TREES (cont'd) LIGHT MOISTURE TYPE BOTANICAL NAME COMMON NAME STREET SUN PART SHADE DRY MOIST WET TREE SHADE DECIDUOUS (cont'd) Fraxinus americana White Ash x x x x Fraxinus pennsylvanica Green Ash x x x x x Gleditsia triacanthos v. -

Northern Pin Oak Quercus Ellipsoidalis

Smart tree selections for communities and landowners Northern Pin Oak Quercus ellipsoidalis Height: 50’ - 70’ Spread: 40’ - 60’ Site characteristics: Full sun, dry to medium moisture, well-drained soils Zone: 4 - 7 Wet/dry: Tolerates dry soils Native range: North Central United States pH: ≤ 7.5 Shape: Cylindrical shape and rounded crown; upper branches are ascending while lower branches are descending Foliage: Dark green leaves in summer, russet-red in fall Other: Elliptic acorns mature after two seasons Additional: Tolerates neutral pH better than pin oak (Quercus palustris) Pests: Oak wilt, chestnut blight, shoestring root rot, anthracnose, oak leaf blister, cankers, leaf spots and powdery mildew. Potential insect pests include scales, oak skeletonizers, leafminers, galls, oak lace bugs, borers, caterpillars and nut weevils. Jesse Saylor, MSU Jesse Saylor, Joseph O’Brien, Bugwood.org Joseph O’Brien, MSU Bert Cregg, Map indicates species’ native range. U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Content development: Dana Ellison, Tree form illustrations: Marlene Cameron. Smart tree selections for communities and landowners Bert Cregg and Robert Schutzki, Michigan State University, Departments of Horticulture and Forestry A smart urban or community landscape has a diverse combination of trees. The devastation caused by exotic pests such as Dutch elm disease, chestnut blight and emerald ash borer has taught us the importance of species diversity in our landscapes. Exotic invasive pests can devastate existing trees because many of these species may not have evolved resistance mechanisms in their native environments. In the recent case of emerald ash borer, white ash and green ash were not resistant to the pest and some communities in Michigan lost up to 20 percent of their tree cover. -

An Updated Infrageneric Classification of the North American Oaks

Article An Updated Infrageneric Classification of the North American Oaks (Quercus Subgenus Quercus): Review of the Contribution of Phylogenomic Data to Biogeography and Species Diversity Paul S. Manos 1,* and Andrew L. Hipp 2 1 Department of Biology, Duke University, 330 Bio Sci Bldg, Durham, NC 27708, USA 2 The Morton Arboretum, Center for Tree Science, 4100 Illinois 53, Lisle, IL 60532, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The oak flora of North America north of Mexico is both phylogenetically diverse and species-rich, including 92 species placed in five sections of subgenus Quercus, the oak clade centered on the Americas. Despite phylogenetic and taxonomic progress on the genus over the past 45 years, classification of species at the subsectional level remains unchanged since the early treatments by WL Trelease, AA Camus, and CH Muller. In recent work, we used a RAD-seq based phylogeny including 250 species sampled from throughout the Americas and Eurasia to reconstruct the timing and biogeography of the North American oak radiation. This work demonstrates that the North American oak flora comprises mostly regional species radiations with limited phylogenetic affinities to Mexican clades, and two sister group connections to Eurasia. Using this framework, we describe the regional patterns of oak diversity within North America and formally classify 62 species into nine major North American subsections within sections Lobatae (the red oaks) and Quercus (the Citation: Manos, P.S.; Hipp, A.L. An Quercus Updated Infrageneric Classification white oaks), the two largest sections of subgenus . We also distill emerging evolutionary and of the North American Oaks (Quercus biogeographic patterns based on the impact of phylogenomic data on the systematics of multiple Subgenus Quercus): Review of the species complexes and instances of hybridization.