Please Scroll Down for Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Upper Extremity Last Updated: 21-10-2017

Results Table Video Game Training – upper extremity Last updated: 21-10-2017 Author, Year Outcome and significance: Sample size Intervention PEDro Score, Country (+) significant (-) not significant Chen et al., 2015 28 patients with chronic Nintendo WiiTM upper extremity training (n=9) At 8 weeks (post-treatment): PEDro score: N/A (quasi- stroke vs. (-) Fugl-Meyer Assessment experimental study design) XaviX®Port upper extremity training (n=11) (-) Box and Block Test Country: Taiwan vs. (-) Functional Independence Measure Conventional upper extremity equipment (n=8) (-) Range of motion (UE - proximal, distal) Treatment details: (+) Motivation and enjoyment interviewer- 30-minutes/session, 3 times/week for 8 weeks. administered questionnaire* Nintendo WiiTM: bowling and boxing games. * Enjoyment was significantly greater in the XaviX®Port: bowling and ladder climbing games. Nintendo WiiTM and XaviX®Port groups vs. Conventional upper extremity equipment: Curamotion conventional rehabilitation group. exerciser and climbing board and bar. All groups also received conventional rehabilitation (physical therapy, occupational therapy) for 1 hour/session, 3 times/week for 8 weeks. Choi et al., 2014 20 patients with Nintendo WiiTM upper extremity training (n=10) At 4 weeks (post-treatment): PEDro score: 8 acute/subacute stroke vs. (-) Fugl-Meyer Assessment – Upper extremity Country: Korea Occupational therapy (OT) upper extremity training score (n=10) (-) Manual Function Test Treatment details: (-) Box and Block Test 30 minutes/session, 5 times/week for 4 weeks. (-) Grip strength (dynamometer) Nintendo WiiTM: Wii Sports and Resort programs (-) Korean version of the Mini-Mental State consisting of 12 games such as swordplay, table tennis, Examination and canoe games performed with the affected UE. -

University of Bath Research Portal

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Bath Research Portal Citation for published version: Mackintosh, KA, Standage, M, Staiano, AE, Lester, L & McNarry, MA 2016, 'Investigating the Physiological and Psychosocial Responses of Single- and Dual-Player Exergaming in Young Adults', Games for Health Journal, vol. 5, no. 6, pp. 375-381. https://doi.org/10.1089/g4h.2016.0015 DOI: 10.1089/g4h.2016.0015 Publication date: 2016 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication Final publication is available from Mary Ann Liebert, Inc., publishers http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/g4h.2016.0015 Copyright©2016 Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. publishers. University of Bath General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 13. May. 2019 1 Running Title: Single- and Dual-player exergaming in adults 2 3 4 5 Investigating the Physiological and Psychosocial Responses of Single- and Dual-Player 6 Exergaming in Young Adults 7 8 Kelly Mackintosh,1 Martyn Standage,2 Amanda E. Staiano,3 Leanne Lester,4 Melitta McNarry1 9 1 College of Engineering, Swansea University, Wales, UK, 2 Department for Health, University of 10 Bath, England, UK, 3 Pennington Biomedical Research Center, 4 School of Sport Science, Exercise 11 and Health, University of Western Australia 12 13 Corresponding Author: Kelly Mackintosh 14 15 1 Abstract 2 Objective: 3 This study investigated the effect of acute exergaming on the physiological and psychosocial responses 4 of young adults and the modulatory effect of a single- or dual-player game play situation. -

Assessment of Enjoyment and Intensity of Physical Activity In

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 12 August 2019 doi:10.20944/preprints201908.0146.v1 Peer-reviewed version available at Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3673; doi:10.3390/ijerph16193673 1 Article 2 Assessment of enjoyment and intensity of physical 3 activity in immersive virtual reality on the 4 omni-directional Omni treadmill and Icaros flight 5 simulator in the context of recommendations for 6 health 7 Małgorzata Dębska1, Jacek Polechoński1,*, Arkadiusz Mynarski1, Piotr Polechoński2 8 1 Institute of Sport Sciences, The Jerzy Kukuczka Academy of Physical Education in Katowice, 43-512 9 Katowice, Poland; [email protected] (M.D.), [email protected] (J.P.), 10 [email protected] (A.M.) 11 2 Faculty of Physiotherapy, The Jerzy Kukuczka Academy of Physical Education in Katowice, 43-512 12 Katowice, Poland; [email protected] (P.P.) 13 * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +48-32-207-5358 14 15 Abstract: The aim of the study is to assess enjoyment and intensity of physical exercise while 16 practicing physical activity (PA) in immersive virtual reality (IVR) using innovative training 17 devices (omni-directional Omni treadmill and Icaros Pro flight simulator). The study also contains 18 the results of subjective research on the usefulness of such a form of PA in the opinion of users. In 19 total, 61 adults (10 women and 50 men) took part in the study. To assess the enjoyment level (EL) 20 Interest/Enjoyment subscale of Intrinsic Motivation Inventory (IMI) was used. Exercise intensity 21 was assessed during 10-minute sessions of active video games (AVGs) in IVR based on heart rate 22 (HR). -

(Title of the Thesis)*

DESIGN ASPECTS OF MULTIPLAYER EXERGAMES [TECHNICAL REPORT 2010-571] Tadeusz B. Stach Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada (February, 2010) Copyright © Tadeusz B. Stach, 2010 Abstract Exergames combine physical movement and entertainment in order to promote physical activity. Multiplayer exergames take advantage of the motivational aspects of group activity by allowing two or more people to play together. Existing research in multiplayer exergames has focused primarily on novel game designs. Currently, there is a lack of understanding on how to support and improve group exercise with exergames. Without a set of design fundamentals, it is difficult to create multiplayer exergames which increase the quality and accessibility of group exercise. This paper synthesizes existing literature into four aspects unique to multiplayer exergames: group formation, play styles, differences in skills and abilities, and quality of exercise. These features make up key design fundamentals specific to multiplayer exergames. ii Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................................ ii Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................ iii List of Figures .................................................................................................................................. v 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................. -

Above and Beyond the Call of Duty Analyse Van De Voorstelling Van De

Universiteit Gent Academiejaar 2011 – 2012 Above and Beyond the Call of Duty Analyse van de voorstelling van de Tweede Wereldoorlog in first person shooter-games d.m.v. een ‘publiekshistorisch’ model Masterproef voorgelegd aan de Faculteit Letteren en Wijsbegeerte voor het behalen van de graad van ‘Master of Arts in de Geschiedenis’ op 10 augustus 2012 Door: Pieter Van den Heede (studentennummer: 00805755) Promotor: Prof. dr. G. Deneckere Commissarissen: A. Froeyman en F. Danniau Universiteit Gent Examencommissie Geschiedenis Academiejaar 2011-2012 Verklaring in verband met de toegankelijkheid van de scriptie Ondergetekende, ………………………………………………………………………………... afgestudeerd als master in de Geschiedenis aan Universiteit Gent in het academiejaar 2011- 2012 en auteur van de scriptie met als titel: ………………………………………………………………………………………………… ………………………………………………………………………………………………… ………………………………………………………………………………………………… ………………………………………………………………………………………………… ………………………………………………………………………………………………… verklaart hierbij dat zij/hij geopteerd heeft voor de hierna aangestipte mogelijkheid in verband met de consultatie van haar/zijn scriptie: o de scriptie mag steeds ter beschikking worden gesteld van elke aanvrager; o de scriptie mag enkel ter beschikking worden gesteld met uitdrukkelijke, schriftelijke goedkeuring van de auteur (maximumduur van deze beperking: 10 jaar); o de scriptie mag ter beschikking worden gesteld van een aanvrager na een wachttijd van … . jaar (maximum 10 jaar); o de scriptie mag nooit ter beschikking worden gesteld van een aanvrager (maximum- duur van het verbod: 10 jaar). Elke gebruiker is te allen tijde verplicht om, wanneer van deze scriptie gebruik wordt gemaakt in het kader van wetenschappelijke en andere publicaties, een correcte en volledige bronver- wijzing in de tekst op te nemen. Gent, ………………………………………(datum) ………………………………………(handtekening) VOORWOORD Graag wil ik de mensen bedanken die op één of andere manier hebben bijgedragen tot de realisatie van deze masterproef. -

Video Gaming, Physical Activity and Health in Young People Lee

Video Gaming, Physical Activity and Health in Young People Lee Edwin Fisher Graves A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Liverpool John Moores University for the degreeof Doctor of Philosophy March 2010 Liverpool John Moores University Candidate declaration form Name of candidate: Lee Edwin Fisher Graves School: Sport and Exercise Sciences Degree for which thesis is submitted: Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) 1. Statement of related studies undertaken in connection with the programme of research I have undertakena programmeof related studies that aimed to develop my research skills and competencein understandinga researchproject. 2. Concurrent registration for two or more academic awards I declare that while registered as a candidate for the University's research degree, I have not been a registered candidate or enrolled student for another award of the Liverpool John Moores University or other academic or professional institution. 3. Material submitted for another award I declarethat no material containedin the thesis has been used in any other submission for an academicaward. Signed: Date: Abstract favourably Increasing physical activity (PA) and reducing the time spent sedentary can behaviour by impact health in youth. Active video games discourage sedentary incorporating PA into video gaming, and have the potential for increasing opportunities for, and the promotion of, PA. The aims of this thesis were to a) compare adolescents' b) energy expenditure (EE) whilst playing sedentary and active video games; to EE examine the contribution of upper limb and total body movement to adolescents' whilst playing non-ambulatory active video games; c) to compare the physiological cost and enjoyment of active video gaming with sedentary video gaming and aerobic exercise in adolescents, and young and older adults; and, d) to evaluate the short-term (12 weeks) effects of a home-based active video gaming intervention on children's habitual PA and sedentary time, behaviour preferences, and, body composition, with a mid-test analysis incorporated at 6 weeks. -

Impact of Nintendo Wii Games on Physical Literacy in Children: Motor Skills, Physical Fitness, Activity Behaviors, and Knowledge

sports Article Impact of Nintendo Wii Games on Physical Literacy in Children: Motor Skills, Physical Fitness, Activity Behaviors, and Knowledge Amanda M. George, Linda E. Rohr *,† and Jeannette Byrne † Received: 5 November 2015; Accepted: 11 January 2016; Published: 15 January 2016 Academic Editor: Eling de Bruin School of Human Kinetics and Recreation, Memorial University, St. John’s, NL A1C 5S7, Canada; [email protected] (A.M.G.); [email protected] (J.B.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-709-864-6202; Fax: +1-709-864-7531 † These authors contributed equally to this work. Abstract: Physical literacy is the degree of fitness, behaviors, knowledge, and fundamental movement skills (agility, balance, and coordination) a child has to confidently participate in physical activity. Active video games (AVG), like the Nintendo Wii, have emerged as alternatives to traditional physical activity by providing a non-threatening environment to develop physical literacy. This study examined the impact of AVGs on children’s (age 6–12, N = 15) physical literacy. For six weeks children played one of four pre-selected AVGs (minimum 20 min, twice per week). Pre and post measures of motivation, enjoyment, and physical literacy were completed. Results indicated a near significant improvement in aiming and catching (p = 0.06). Manual dexterity significantly improved in males (p = 0.001), and females felt significantly less pressured to engage in PA (p = 0.008). Overall, there appears to be some positive impact of an AVG intervention on components of physical literacy. Keywords: physical literacy; children; active video games; motivation 1. Introduction Physical literacy is an important factor in child development. -

Las Consolas De Juego Del Mañana

Universidad Católica “Nuestra Señora de la Asunción” Ingeniería Electrónica Las consolas de juego del mañana Dorian Hildebrandt 2005 Index 1. Introducción 2. Un poco de Historia de consolas 3. Sony Play Station 3 4. Microsoft Xbox 30 5. Nintendo Revolution 6. Lanzamiento de las consolas y precios 7. Conclusión 8. Bibliografía Las consolas del mañana Las consolas de juegos de la próxima generación prometen un “rendimiento casi sin limites”. En tres consolas de la nueva generación son: La PlayStation 3, Xbox 360 y la Nintendo Revolution. El sector de los videojuegos es hoy uno de los más rentables de la industria del entretenimiento. Para muchos es considerado un nuevo arte. Pero lo que sin duda ha conseguido es revolucionar el ocio y el entretenimiento en el hogar. Hoy en día esta revolución sigue su curso, y si en su primera etapa se aprovechó del potencial de la televisión para desarrollarse en la actualidad son Internet y las conexiones inalámbricas las que llevarán en voladas el desarrollo del sector. Un poco de Historia La historia de los videojuegos se remonta a 1958 cuando Bill Nighinbottham mostró la versión electrónica de un deporte parecido al tenis en una feria tecnológica. El invento no tuvo su reflejo comercial hasta 1971, año en que apareció la Odyssey, sistema que permitía jugar al simulador de Hill en la televisión. Pero el nacimiento de la industria del videojuego no llegó hasta el año 1972, cuando Nolan Bushnell y Ted Dabney fundaron Atari. Bushnell comprendió que la popularización de los videojuegos llegaría a través de las máquinas recreativas de monedas, y contrató a un programador de Odyssey para desarrollar uno de los juegos más exitosos de la historia, Pong. -

Games for Rehabilitation Sheryl Flynn PT, Phd Belinda Lange Physio, Phd Tuesday, June 29 from 3:00-4:15Pm

Games for Rehabilitation Sheryl Flynn PT, PhD Belinda Lange Physio, PhD Tuesday, June 29 from 3:00-4:15pm. Sheryl Flynn is a consultant and researcher in the VRPSYCH Lab at the Institute for Creative Technologies, University of Southern California and she is the founder and CEO of Blue Marble Game Company, Altadena, CA. ([email protected]) Belinda Lange Bsc., Ph.D is a senior research associate in the VRPSYCH Lab at the Institute for Creative Technologies. Institute for Creative Technologies, University of Southern California, 13274 Fiji Way, Marina Del Rey, CA 90292 ([email protected]). Using video games for rehabilitation purposes combines innovative computer technology with contemporary rehabilitation and neuroplasticity theories. With technological advances video games can now be played with little active movement and minimal fine motor control. These games are motivating and fun while simultaneously pushing the brain and body to recover. The purpose of this presentation is to provide the audience with 1) provide a review of relevant literature in support of video games for rehabilitation, 2) discuss current off the shelf video games and controllers appropriate for rehabilitation, and 3) provide explicit examples of use of games in the clinic. I. Review of relevant literature in support of video games for rehabilitation 1. Video Games for Rehabilitation Reviews a. Weiss P, et al. JNER. 2004;1(1):12. b. Sveistrup H. JNER. 2004;1:10-18. c. Deutsch & Mirelman Topics in Stroke Rehab 2007 d. Henderson et al Topics in Stroke Rehab 2007 e. Adamovich et al, Neurorehabilitation 2009 f. Special Issue of Physical Therapy Reviews (PTR) October 2009 2. -

Enjoyment and Intensity of Physical Activity in Immersive Virtual Reality Performed on Innovative Training Devices in Compliance with Recommendations for Health

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article Enjoyment and Intensity of Physical Activity in Immersive Virtual Reality Performed on Innovative Training Devices in Compliance with Recommendations for Health Małgorzata D˛ebska 1, Jacek Polecho ´nski 1,* , Arkadiusz Mynarski 1 and Piotr Polecho ´nski 2 1 Institute of Sport Sciences, The Jerzy Kukuczka Academy of Physical Education in Katowice, 43-512 Katowice, Poland; [email protected] (M.D.); [email protected] (A.M.) 2 Faculty of Physiotherapy, The Jerzy Kukuczka Academy of Physical Education in Katowice, 43-512 Katowice, Poland; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +48-32-207-5358 Received: 8 August 2019; Accepted: 27 September 2019; Published: 30 September 2019 Abstract: The aim of the study is to assess the enjoyment and intensity of physical exercise while practicing physical activity (PA) in immersive virtual reality (IVR) using innovative training devices (omni-directional Omni treadmill and Icaros Pro flight simulator). The study also contains the results of subjective research on the usefulness of such a form of PA in the opinion of users. In total, 61 adults (10 women and 51 men) took part in the study. To assess the enjoyment level (EL) Interest/Enjoyment subscale of Intrinsic Motivation Inventory (IMI) was used. Exercise intensity was assessed during 10-min sessions of active video games (AVGs) in IVR based on heart rate (HR). The average enjoyment level during physical exercise in IVR on the tested training devices was high (Omni 5.74 points, Icaros 5.60 points on a 1–7 Likert scale) and differed significantly in favor of PA on Omni. -

Exergames Experience in Physical Education: a Review

PHYSICAL CULTURE AND SPORT. STUDIES AND RESEARCH DOI: 10.2478/pcssr-2018-0010 Exergames Experience in Physical Education: A Review Authors’ contribution: Cesar Augusto Otero Vaghetti1A-E, Renato Sobral A) conception and design 2A-E 1A-E of the study Monteiro-Junior , Mateus David Finco , Eliseo B) acquisition of data Reategui3A-E, Silvia Silva da Costa Botelho 4A-E C) analysis and interpretation of data D) manuscript preparation 1Federal University of Pelotas, Brazil E) obtaining funding 2State University of Montes Carlos, Brazil 3Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil 4Federal University of Rio Grande, USA ABSTRACT Exergames are consoles that require a higher physical effort to play when compared to traditional video games. Active video games, active gaming, interactive games, movement-controlled video games, exertion games, and exergaming are terms used to define the kinds of video games in which the exertion interface enables a new experience. Exergames have added a component of physical activity to the otherwise motionless video game environment and have the potential to contribute to physical education classes by supplementing the current activity options and increasing student enjoyment. The use of exergames in schools has already shown positive results in the past through their potential to fight obesity. As for the pedagogical aspects of exergames, they have attracted educators’ attention due to the large number of games and activities that can be incorporated into the curriculum. In this way, the school must consider the development of a new physical education curriculum in which the key to promoting healthy physical activity in children and youth is enjoyment, using video games as a tool. -

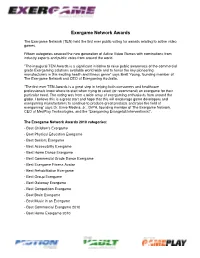

Exergame Network Awards

Exergame Network Awards The Exergame Network (TEN) held the first ever public voting for awards relating to active video games. Fifteen categories covered the new generation of Active Video Games with nominations from industry experts and public votes from around the world. ”The inaugural TEN Awards is a significant initiative to raise public awareness of the commercial grade Exergaming solutions available world wide and to honor the key pioneering manufacturers in this exciting health and fitness genre” says Brett Young, founding member of The Exergame Network and CEO of Exergaming Australia. ”The first ever TEN Awards is a great step in helping both consumers and healthcare professionals know where to start when trying to select (or recommend) an exergame for their particular need. The voting was from a wide array of exergaming enthusiasts from around the globe. I believe this is a great start and hope that this will encourage game developers and exergaming manufacturers to continue to produce great products and raise the field of exergaming” says Dr. Ernie Medina, Jr., DrPH, founding member of The Exergame Network, CEO of MedPlay Technologies, and the “Exergaming Evangelist/Interventionist”. The Exergame Network Awards 2010 categories: - Best Children's Exergame - Best Physical Education Exergame - Best Seniors Exergame - Best Accessibility Exergame - Best Home Dance Exergame - Best Commercial Grade Dance Exergame - Best Exergame Fitness Avatar - Best Rehabilitation Exergame - Best Group Exergame - Best Gateway Exergame - Best Competition Exergame - Best Brain Exergame - Best Music in an Exergame - Best Commercial Exergame 2010 - Best Home Exergame 2010 1. Best Children’s Exergame Award that gets younger kids moving with active video gaming - Dance Dance Revolution Disney Grooves by Konami - Wild Planet Hyper Dash - Atari Family Trainer - Just Dance Kids by Ubisoft - Nickelodeon Fit by 2K Play Dance Dance Revolution Disney Grooves by Konami 2.