Active Gaming: the Future of Play? S Lisa Witherspoon John P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Use of Computer Simulation Games for Instructional and Recruiting Purposes in Middle School and Jr

Use of Computer Simulation Games for Instructional and Recruiting Purposes in Middle School and Jr. High Research Experiences for Teachers (RET) 2010 Melissa Miller, Randall Reynolds Science Teacher Lynch Middle School/Math Teacher Gravette Junior High School Abstract The 2010 Summer RET program at the University of Arkansas provided an opportunity for two public school teachers to conduct further research in the area of using computer simulation games for instructional purposes as well as for the recruitment of potential industrial engineering students. Emphasis was placed on how industrial engineering concepts could be explored through the use of a simulation game that would provide a high interest classroom project based upon sound curriculum. The challenge for the project was to refine an academic competition involving a simulation-based video game relating to Industrial Engineering. The project was divided into 2 divisions, one for junior level students in grades 6 – 8 and one for senior level students in grades 9 – 12. Obviously, a major issue was designing the competitions with a proper level of difficulty for both age groups while keeping the subject matter relevant to meaningful engineering concepts and instructional frameworks. The competitions were intended to help students acquire fundamental problem solving capabilities as well as a basic understanding of some tools used in Industrial Engineering and logistics. This project was completed under the leadership of two mentoring professors: Dr. Richard Cassady and Dr. Ed Pohl, who provided guidance and also secured funding necessary to support the implementation of the competition by providing the necessary supplies through the support of Dr. -

Discussing on Gamification for Elderly Literature, Motivation and Adherence

Discussing on Gamification for Elderly Literature, Motivation and Adherence Jose Barambones1, Ali Abavisani1, Elena Villalba-Mora1;2, Miguel Gomez-Hernandez1;3 and Xavier Ferre1 1Center for Biomedical Technology, Universidad Politecnica´ de Madrid, Spain 2Biomedical Research Networking Centre in Bioengineering Biomaterials and Nanomedicine (CIBER-BBN), Spain 3Aalborg University, Denmark Keywords: Gamification, Serious Games, Exergames, Elderly, Frailty, Discussion. Abstract: Gamification and Serious games techniques have been accepted as an effective method to strengthen the per- formance and motivation of people in education, health, entertainment, workplace and business. Concretely, exergames have been increasingly applied to raise physical activities and health or physical performance im- provement among elders. To the extend of our understanding, there is an extensive research on gamification and serious games for elderly in health. However, conducted studies assume certain issues regarding context biases, lack of applied guidelines or standardization, or weak results. We assert that a greater effort must be applied to explore and understand the needs and motivations of elderly players. Further, for improving the impact in proof-of-concept solutions and experiments some well-known guidelines or foundations must be adopted. In our current work, we are applying exergames on elderly with frailty condition in order to improve patient engagement in healthcare prevention and intervention. We suggest that to detect and reinforce such traits on elderly is adequate to extend the literature properly. 1 INTRODUCTION preserve the intrinsic capacity of the individual, its en- vironmental characteristics and their interaction. In In recent years, a rapid increase of consumer soft- parallel, by 2050 life expectancy will surpass 90 years ware inspired by the video-gaming has been per- and one in six people in the world will be over age 65 ceived. -

Links to the Past User Research Rage 2

ALL FORMATS LIFTING THE LID ON VIDEO GAMES User Research Links to Game design’s the past best-kept secret? The art of making great Zelda-likes Issue 9 £3 wfmag.cc 09 Rage 2 72000 Playtesting the 16 neon apocalypse 7263 97 Sea Change Rhianna Pratchett rewrites the adventure game in Lost Words Subscribe today 12 weeks for £12* Visit: wfmag.cc/12weeks to order UK Price. 6 issue introductory offer The future of games: subscription-based? ow many subscription services are you upfront, would be devastating for video games. Triple-A shelling out for each month? Spotify and titles still dominate the market in terms of raw sales and Apple Music provide the tunes while we player numbers, so while the largest publishers may H work; perhaps a bit of TV drama on the prosper in a Spotify world, all your favourite indie and lunch break via Now TV or ITV Player; then back home mid-tier developers would no doubt ounder. to watch a movie in the evening, courtesy of etix, MIKE ROSE Put it this way: if Spotify is currently paying artists 1 Amazon Video, Hulu… per 20,000 listens, what sort of terrible deal are game Mike Rose is the The way we consume entertainment has shifted developers working from their bedroom going to get? founder of No More dramatically in the last several years, and it’s becoming Robots, the publishing And before you think to yourself, “This would never increasingly the case that the average person doesn’t label behind titles happen – it already is. -

University of Bath Research Portal

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Bath Research Portal Citation for published version: Mackintosh, KA, Standage, M, Staiano, AE, Lester, L & McNarry, MA 2016, 'Investigating the Physiological and Psychosocial Responses of Single- and Dual-Player Exergaming in Young Adults', Games for Health Journal, vol. 5, no. 6, pp. 375-381. https://doi.org/10.1089/g4h.2016.0015 DOI: 10.1089/g4h.2016.0015 Publication date: 2016 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication Final publication is available from Mary Ann Liebert, Inc., publishers http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/g4h.2016.0015 Copyright©2016 Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. publishers. University of Bath General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 13. May. 2019 1 Running Title: Single- and Dual-player exergaming in adults 2 3 4 5 Investigating the Physiological and Psychosocial Responses of Single- and Dual-Player 6 Exergaming in Young Adults 7 8 Kelly Mackintosh,1 Martyn Standage,2 Amanda E. Staiano,3 Leanne Lester,4 Melitta McNarry1 9 1 College of Engineering, Swansea University, Wales, UK, 2 Department for Health, University of 10 Bath, England, UK, 3 Pennington Biomedical Research Center, 4 School of Sport Science, Exercise 11 and Health, University of Western Australia 12 13 Corresponding Author: Kelly Mackintosh 14 15 1 Abstract 2 Objective: 3 This study investigated the effect of acute exergaming on the physiological and psychosocial responses 4 of young adults and the modulatory effect of a single- or dual-player game play situation. -

A Systematic Review on the Effectiveness of Gamification Features in Exergames

Proceedings of the 50th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences | 2017 How Effective Is “Exergamification”? A Systematic Review on the Effectiveness of Gamification Features in Exergames Amir Matallaoui Jonna Koivisto Juho Hamari Ruediger Zarnekow Technical University of School of Information School of Information Technical University of Berlin Sciences, Sciences, Berlin amirqphj@ University of Tampere University of Tampere ruediger.zarnekow@ mailbox.tu-berlin.de [email protected] [email protected] ikm.tu-berlin.de One of the most prominent fields where Abstract gamification and other gameful approaches have been Physical activity is very important to public health implemented is the health and exercise field [7], [3]. and exergames represent one potential way to enact it. Digital games and gameful systems for exercise, The promotion of physical activity through commonly shortened as exergames, have been gamification and enhanced anticipated affect also developed extensively during the past few decades [8]. holds promise to aid in exercise adherence beyond However, due to the technological advancements more traditional educational and social cognitive allowing for more widespread and affordable use of approaches. This paper reviews empirical studies on various sensor technologies, the exergaming field has gamified systems and serious games for exercising. In been proliferating in recent years. As the ultimate goal order to gain a better understanding of these systems, of implementing the game elements to any non- this review examines the types and aims (e.g. entertainment context is most often to induce controlling body weight, enjoying indoor jogging…) of motivation towards the given behavior, similarly the the corresponding studies as well as their goal of the exergaming approaches is supporting the psychological and physical outcomes. -

Video Games Review DRAFT5-16

Video Games: History, Technology, Industry, and Research Agendas Table of Contents I. Overview ....................................................................................................................... 1 II. Video Game History .................................................................................................. 7 III. Academic Approaches to Video Games ................................................................. 9 1) Game Studies ....................................................................................................................... 9 2) Video Game Taxonomy .................................................................................................... 11 IV. Current Status ........................................................................................................ 12 1) Arcade Games ................................................................................................................... 12 2) Console Games .................................................................................................................. 13 3) PC Standalone Games ...................................................................................................... 14 4) Online Games .................................................................................................................... 15 5) Mobile Games .................................................................................................................... 16 V. Recent Trends .......................................................................................................... -

Fallout 3 Pc Download Meaga Fallout 3 Full Pc Game + Crack Cpy CODEX Torrent Free 2021

fallout 3 pc download meaga Fallout 3 Full Pc Game + Crack Cpy CODEX Torrent Free 2021. Fallout 3 Crack Game Gameplay New Vegas is a game from 2021. It is considered the most popular game since its launch. With it, you can create your own character of your choice and immerse yourself in a post-apocalyptic and inspiring world. In this game, every minute you will experience a war and you need to survive. Also, the game starts from here; The Wanderer is tasked with arresting a character who was trying to escape from James. Fallout 3 Crack Game Cpy: The latest version of Fallout 4 turned out to be obvious that the computer game is extremely famous and it just blew up all the racks. Additionally, it includes a player character known as Lonely Wanderer, who is a little boy. The fallout shelter is located in Washington, DC. The vault was sealed for 200 years until the player’s father, James, opened the door and disappeared without any information. The surrender took place on November 10, 2015 and, as shown by various information and realities, surveys of players and experts, a measure of fanart and conversations. Alternatively, you can also try Ashampoo Winoptimizer. Fallout 3 Crack Game Cpy: Download Fallout 3 Crack Ps4 was first released on October 25, 2008 in the United States. Also, it is available on Xbox 360, PC, PS4, Ps3, and other gaming stations. Similarly, the game features realistic first- or third-person combat. The game is planned for the retro-futuristic United States between the People’s Republic of China and America. -

A Validation of a Game-Based Assessment for the Measurement of Vocational Interest

A VALIDATION OF A GAME-BASED ASSESSMENT FOR THE MEASUREMENT OF VOCATIONAL INTEREST A Thesis submitted to the faculty of San Francisco State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree Master of Science In Psychology: Industrial/Organizational Psychology by Hope Elizabeth Wear San Francisco, California May 2018 Copyright by Hope Elizabeth Wear 2018 CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL I certify that I have read A Validation of a Game-Based Assessment for the Measurement of Vocational Interest by Hope Elizabeth Wear, and that in my opinion this work meets the criteria for approving a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree Master of Science in Psychology: Industrial/Organizational Psychology at San Francisco State University. Chris Wright, Ph.D. Professor A VALIDATION OF A GAME-BASED ASSESSMENT FOR THE MEASUREMENT OF VOCATIONAL INTEREST Hope Elizabeth Wear San Francisco, California 2018 Game-based assessments (GBAs) are a new type of technologically-based assessment tool which allow for traditional selection concepts to be measured from gameplay behaviors (e.g., completing levels by following game rules). GBAs use game elements to create an immersive environment which changes how assessments are traditionally measured but retains the psychometric properties within the game to assess a variety of knowledge, skills and abilities. In this study we examined the validity of a GBA for use as a measure of RIASEC vocational interests from Holland (1985). Participants played the GBA as well as completed traditional measures of RIASEC interests. We compared the scores from participants for congruence across the different measures using a multitrait-multimethod matrix (MTMM). -

The Effects of Visual Feedback in Therapeutic Exergaming on Motor Task Accuracy

International Conference on Virtual Rehabilitation 2011 Rehab Week Zurich, ETH Zurich Science City, Switzerland, June 27 - 29, 2011 The Effects of Visual Feedback in Therapeutic Exergaming on Motor Task Accuracy Julie Doyle, Daniel Kelly, Matt Patterson and Brian Caulfield, Member, IEEE AbstractPoor exercise technique and lack of adherence technology as input into therapeutic exergaming provides a during home exercise are implicated in preventing a full measure of objective feedback for both the therapist and the recovery to peak physical function during rehabilitation. It is patient. Making rehabilitation engaging or fun can increase a widely believed that therapeutic exergaming has the potential patient's motivation to adhere to their exercise programme at to solve these issues. However, the field is still young and there home and it is widely believed that a gaming environment is little empirical evidence supporting, in particular, its effectiveness in helping the patient to maintain correct can provide this fun, motivating context [6], [7], [8]. technique. In this paper we present preliminary results from a In fact, much research into rehabilitation through study to examine the effects that visual feedback during technology stresses the importance of feedback to motivate exergaming has on a person's accuracy in performing a motor the rehabilitation process [5], [9]. There is much less task. Our study showed that interacting with a game discussion on the equally important topic of whether such incorporating simple visual feedback results in improved technology can ensure maintenance of correct technique accuracy compared to performing exercise from memory or with limited feedback in the form of an instructional video when exercising. -

Assessment of Enjoyment and Intensity of Physical Activity In

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 12 August 2019 doi:10.20944/preprints201908.0146.v1 Peer-reviewed version available at Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3673; doi:10.3390/ijerph16193673 1 Article 2 Assessment of enjoyment and intensity of physical 3 activity in immersive virtual reality on the 4 omni-directional Omni treadmill and Icaros flight 5 simulator in the context of recommendations for 6 health 7 Małgorzata Dębska1, Jacek Polechoński1,*, Arkadiusz Mynarski1, Piotr Polechoński2 8 1 Institute of Sport Sciences, The Jerzy Kukuczka Academy of Physical Education in Katowice, 43-512 9 Katowice, Poland; [email protected] (M.D.), [email protected] (J.P.), 10 [email protected] (A.M.) 11 2 Faculty of Physiotherapy, The Jerzy Kukuczka Academy of Physical Education in Katowice, 43-512 12 Katowice, Poland; [email protected] (P.P.) 13 * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +48-32-207-5358 14 15 Abstract: The aim of the study is to assess enjoyment and intensity of physical exercise while 16 practicing physical activity (PA) in immersive virtual reality (IVR) using innovative training 17 devices (omni-directional Omni treadmill and Icaros Pro flight simulator). The study also contains 18 the results of subjective research on the usefulness of such a form of PA in the opinion of users. In 19 total, 61 adults (10 women and 50 men) took part in the study. To assess the enjoyment level (EL) 20 Interest/Enjoyment subscale of Intrinsic Motivation Inventory (IMI) was used. Exercise intensity 21 was assessed during 10-minute sessions of active video games (AVGs) in IVR based on heart rate 22 (HR). -

Exerlearn Bike: an Exergaming System for Children's Educational and Physical Well-Being by Rajwa Alharthi a Thesis Submitted T

EXERLEARN BIKE: AN EXERGAMING SYSTEM FOR CHILDREN’S EDUCATIONAL AND PHYSICAL WELL-BEING BY RAJWA ALHARTHI A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER IN COMPUTER SCIENCE OTTAWA-CARLETON INSTITUTE FOR COMPUTER SCIENCE SCHOOL OF ELECTRICAL ENGINEERING AND COMPUTER SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF OTTAWA © RAJWA ALHARTHI, OTTAWA, CANADA 2012 Abstract Inactivity and sedentary behavioural patterns among children contribute greatly to a wide range of diseases including obesity, cancer, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes. It is also associated with other important health effects like mental health issues, anxiety, and depression. In order to reduce these trends, we need to focus on the highest contributing factor, which is lack of physical activity in children’s daily lives. 'Exergames' are believed to be a very good solution in promoting physical activity in children. Such games encourage children to engage in physical activity for long periods of time while enjoying their gaming experience. The purpose of this thesis is to provide means of directing child behaviour in a healthy direction by using gaming enhancements that encourage physical exertion. We believe that the combination of both exercising and learning modalities in an attractive gaming environment could be more beneficial for the child's well-being. In order to achieve this, we present an adaptive exergaming system, the "ExerLearn Bike", which combines physical, gaming, and educational features. The main idea of the system is to have children learn about new objects, new language, practice their math skills, and improve their cognitive ability through enticing games and effective exercise. -

In the Archives Here As .PDF File

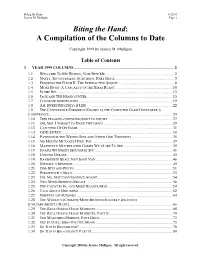

Biting the Hand 6/12/01 Jessica M. Mulligan Page 1 Biting the Hand: A Compilation of the Columns to Date Copyright 1999 by Jessica M. Mulligan Table of Contents 1 YEAR 1999 COLUMNS ...................................................................................................2 1.1 WELCOME TO MY WORLD; NOW BITE ME....................................................................2 1.2 NASTY, INCONVENIENT QUESTIONS, PART DEUX...........................................................5 1.3 PRESSING THE FLESH II: THE INTERACTIVE SEQUEL.......................................................8 1.4 MORE BUGS: A CASUALTY OF THE XMAS RUSH?.........................................................10 1.5 IN THE BIZ..................................................................................................................13 1.6 JACK AND THE BEANCOUNTER....................................................................................15 1.7 COLOR ME BONEHEADED ............................................................................................19 1.8 AH, SWEET MYSTERY OF LIFE ................................................................................22 1.9 THE CONFERENCE FORMERLY KNOWN AS THE COMPUTER GAME DEVELOPER’S CONFERENCE .........................................................................................................................24 1.10 THIS FRAGGED CORPSE BROUGHT TO YOU BY ...........................................................27 1.11 OH, NO! I FORGOT TO HAVE CHILDREN!....................................................................29