Towards a Transit-Oriented Affordable Housing (Toah) Strategy in Mexico City

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Baseline Study of Land Markets in and Around Mexico City's Current And

Baseline Study of Land Markets in and Around Mexico City’s Current and New International Airports Report to the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy July 10, 2017 Paavo Monkkonen UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs Jorge Montejano Escamilla Felipe Gerardo Avila Jimenez Centro de Investigación en Geografía y Geomática 1 Executive Summary Government run urban mega-projects can have a transformative impact on local property and land markets, creating significant increases in the value of land through investment by the state. The construction of a New International Airport and the redevelopment of the existing International Airport will be one of the largest public infrastructure projects in Mexico City in recent history. The potential impacts on the price of nearby land warrants consideration of a land value capture program. Regardless of the form this program takes, the city needs an accurate and well-justified baseline measure of the value of land and property proximate to the two airport sites. This report contains three parts. The first is a review of relevant academic literature on property appraisals, the impacts of airports and mega-projects on land and property values, the role of value capture in infrastructure investment, and the methods and tools through which land value impacts can be estimated. This latter component of the literature review is especially important. Much of the data on land and property values in Mexico City are from appraisals and estimates rather than actual transaction records, and the methodology governments use to assess land values plays an important role in the credibility and political feasibility of efforts to recapture value increases. -

Capítulo 2 ORDENAMIENTO DEL TERRITORIO, ESTRUCTURA URBANA Y HABITABILIDAD

Ciudad de México 2020. Un diagnóstico de la desigualdad socio territorial CAPÍTULO 2 ORDENAMIENTO DEL TERRITORIO, ESTRUCTURA URBANA Y HABITABILIDAD 60 Ciudad de México 2020. Un diagnóstico de la desigualdad socio territorial Capítulo 2 ORDENAMIENTO DEL TERRITORIO, ESTRUCTURA URBANA Y HABITABILIDAD El conocimiento sobre los problemas asociados con el ordenamiento del territorio, con la estructura urbana y con la habitabilidad en la Ciudad de México incluye el análisis de los asentamientos irregula- res en la Ciudad, de las condiciones de habitabilidad de las viviendas —tanto del acceso como de sus características físicas— y de la desigualdad en torno al uso de los sistemas de transporte urbano para la movilidad de las personas. 1. Las aristas de la desigualdad urbana El desarrollo urbano, en su comprensión más formal, incluye procesos de planeación y ejecución de acciones para la zonificación del tejido urbano de acuerdo con la asignación de usos del suelo y los lineamientos de construcción contenidos en los ordenamientos aplicables. Se trata, principalmente, de una política reguladora del crecimiento que debe asegurar, además, dimensiones como la protec- ción ambiental. Los criterios que rigen la normatividad al respecto son de diversa índole, pues abarcan consideraciones de racionalidad económica y de rentabilidad, pero también culturales, de preserva- ción y recuperación del entorno histórico, y de conservación ambiental. Sin embargo, la aplicación de estos marcos regulatorios no ha evitado el surgimiento y proliferación de asentamientos -

Nuevo Polanco: Un Caso De Gentrificación Indirecta En La Ciudad De

DIVISIÓN DE CIENCIAS SOCIALES Y HUMANIDADES Departamento de Sociología Licenciatura en Geografía Humana Nuevo Polanco: Un caso de gentrificación indirecta en la Ciudad de México. 165 pp. Investigación Terminal para obtener el título de: LICENCIADO EN GEOGRAFÍA HUMANA PRESENTA Emiliano Rojas García Lector. Dr. Adrián Hernández Cordero 1 Índice Carta de dictaminación del Lector Dr. Hernández Cordero……………..………….4 Capítulo I. Introducción................................................…............................................... 5 Construcción del objeto de investigación....................................….......8 Capítulo II. Gentrificación............................................….........................….................12 Origen..............................................................................................….....14 La complejización del concepto: debate producción-consumo.….....17 La gentrificación como un fenómeno global.............................….......27 América Latina y la entrada al nuevo milenio.…..….........................30 Conclusiones.............................................................…..........................36 Capítulo III. Metodología y origen de datos.......................................…..........................39 Definición área de estudio......................................…..........................39 Metodología.................................................................................…......41 Datos cuantitativos......................................................................…... -

Mitikah Ciudad Viva. Actores, Toma De Decisiones Y Conflicto Urbano. Mtro

Mitikah Ciudad Viva. Actores, toma de decisiones y conflicto urbano. Mtro. Mario Ramírez Chávez1 [email protected] Facultad de Ciencias Políticas y Sociales de la UNAM. Eje Temático: Política Municipal, Desarrollo Urbano y Rural, Ciudades Incluyentes y Sostenibilidad. Trabajo preparado para su presentación en el X Congreso Latinoamericano de Ciencia Política de la Asociación Latinoamericana de Ciencias Políticas (ALACIP), en coordinación con la Asociación Mexicana de Ciencias Políticas (AMECIP), organizado en colaboración con el Instituto Tecnológico de Estudios Superiores de Monterrey (ITESM), los días 21 de julio, 1, 2 y 3 de agosto de 2019. 1Candidato a Doctor en Ciencias Políticas y Sociales por la Facultad de Ciencias Políticas y Sociales de la UNAM, líneas de investigación: prospectiva y construcción de escenarios, políticas púbicas diseño y evaluación, gestión del desarrollo urbano. Página 1 de 29 Resumen. En los últimos 20 años en la Ciudad de México, a la par de la transición democrática se dieron una serie de procesos de apertura y democratización de los procesos de toma de decisiones y el reconocimiento de nuevos actores para la hechura de políticas públicas. Dichos fenómenos políticos y administrativos, han sido acompañados de un modelo económico y un modelo y forma de hacer ciudad de carácter neoliberales; mercantilizando el espacio público, el derecho a la vivienda y el derecho a la ciudad, construyendo una ciudad fragmentado, polarizada a partir de la ampliación de las desigualdades socioterritoriales y socioespaciales. Lo anterior ha sido posible, gracias al proceso de control y captura de los procesos y mecanismos de toma de decisiones para la hechura de políticas públicas por una serie de actores individuales y colectivos, los cuales se han aglutinado para conformar coaliciones promotoras de grandes proyectos urbanos como una nueva forma de hacer ciudad en la denominada ciudad central de la Ciudad de México. -

Urban Aerial Cable Cars As Mass Transit Systems Case Studies, Technical Specifications, and Business Models

Urban Aerial Public Disclosure Authorized Cable Cars as Mass Transit Systems Case studies, technical specifications, and business models Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Copyright © 2020 by the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank, Latin America and Caribbean region 1818H Street, N.W. Washington DC 20433, U.S.A. www.worldbank.org All rights reserved This report is a product of consultant reports commissioned by the World Bank. The findings presented in this document are This work is available under the Creative based on official sources of information, interviews, data, and Commons Attribution 4.0 IGO license previous studies provided by the client and on the expertise of (CC BY 4.0 IGO). the consultant. The information contained here has been compiled from historical records, and any projections based Under the Creative Commons thereon may change as a function of inherent market risks and Attribution license, you are free to copy, uncertainties. The estimates presented in this document may distribute, transmit, and adapt this therefore diverge from actual outcomes as a consequence of work, including for commercial future events that cannot be foreseen or controlled, including, purposes, under the following but not limited to, adverse environmental, economic, political, or conditions: Attribution—Please cite the market impacts. work as follows: World Bank Group. Urban Aerial Cable Cars as Mass Transit The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data Systems. Case studies, technical included in this report and accepts no responsibility whatsoever specifications, and business models. for any consequence of their use or interpretation. -

What Light Rail Can Do for Cities

WHAT LIGHT RAIL CAN DO FOR CITIES A Review of the Evidence Final Report: Appendices January 2005 Prepared for: Prepared by: Steer Davies Gleave 28-32 Upper Ground London SE1 9PD [t] +44 (0)20 7919 8500 [i] www.steerdaviesgleave.com Passenger Transport Executive Group Wellington House 40-50 Wellington Street Leeds LS1 2DE What Light Rail Can Do For Cities: A Review of the Evidence Contents Page APPENDICES A Operation and Use of Light Rail Schemes in the UK B Overseas Experience C People Interviewed During the Study D Full Bibliography P:\projects\5700s\5748\Outputs\Reports\Final\What Light Rail Can Do for Cities - Appendices _ 01-05.doc Appendix What Light Rail Can Do For Cities: A Review Of The Evidence P:\projects\5700s\5748\Outputs\Reports\Final\What Light Rail Can Do for Cities - Appendices _ 01-05.doc Appendix What Light Rail Can Do For Cities: A Review of the Evidence APPENDIX A Operation and Use of Light Rail Schemes in the UK P:\projects\5700s\5748\Outputs\Reports\Final\What Light Rail Can Do for Cities - Appendices _ 01-05.doc Appendix What Light Rail Can Do For Cities: A Review Of The Evidence A1. TYNE & WEAR METRO A1.1 The Tyne and Wear Metro was the first modern light rail scheme opened in the UK, coming into service between 1980 and 1984. At a cost of £284 million, the scheme comprised the connection of former suburban rail alignments with new railway construction in tunnel under central Newcastle and over the Tyne. Further extensions to the system were opened to Newcastle Airport in 1991 and to Sunderland, sharing 14 km of existing Network Rail track, in March 2002. -

Políticas Empresarialistas En Los Procesos De Gentrificación En La Ciudad 113 De México

Revista de Geografía Norte Grande, 58: 111-133 (2014)111 Artículos Políticas empresarialistas en los procesos de gentrifi cación en la Ciudad de México1 Patricia Olivera 2 y Víctor Delgadillo3 RESUMEN La reestructuración urbana en la Ciudad de México desde fi nes de la década de 1980 ha dado lugar a diversos procesos asociados con la gentrifi cación, apoyada en la gestión urbana empresarialista, la cual ha facilitado la realización de mega- proyectos inmobiliarios, la revitalización de barrios urbanos, la fragmentación del tejido social y el desplazamiento de población residente, trabajadora y de algunas actividades tradicionales en aquellos espacios urbanos que han sido revalorizados. La complejidad de estos procesos urbanos lleva, en primer lugar a una necesaria refl exión y debate teórico para entender estas profundas transformaciones urba- nas. Para lo cual se examinan las políticas urbanas neoliberales recientes y su vinculación con los diversos procesos de gentrifi cación, sus formas, intensidades y temporalidades diferenciadas y se profundiza en el análisis del Centro Histórico y otros barrios paradigmáticos de la ciudad interior. Palabras clave: Gentrifi cación en la Ciudad de México, megaproyectos urbanos, políticas empresarialistas. ABSTRACT The urban restructuring in Mexico City since the late 1980s has led to various processes associated with gentrifi cation. Urban entrepreneurial management has facilitated the production of real estate megaprojects, the revitalization of urban neighborhoods, the fragmentation of the social fabric and the displacement of resident population, workers, and some traditional activities of those urban spac- es that have been revalued. The complexity of these urban processes leads to a theoretical refl ection and debate necessary to understand these profound urban transformations. -

El Nuevo Proyecto De Ciudad: Del Centro Histórico a Santa Fe

El nuevo proyecto de ciudad: del Centro Histórico a Santa Fe. Segregación, espacio público y conflicto urbano1 Adriana Aguayo Ayala2 Introducción En el presente capítulo se pretenden discutir algunas de las ca- racterísticas del nuevo modelo de ciudad adoptado e impulsado desde la década de los años noventa en la ciudad de México tomando como ejemplo los proyectos de creación de la zona financiera de Santa Fe y la renovación del Centro Histórico. Como se argumentará en las siguientes páginas, desde hace algunas décadas las grandes ciudades del mundo han experimen- tado diversos procesos de reorganización territorial impulsados por políticas urbanas neoliberales sustentadas en la renovación y revitalización de zonas urbanas deterioradas o en la reconver- sión de zonas industriales y pasivos ambientales inoperantes 1 Este trabajo forma parte del proyecto Ciudad global, procesos locales: conflictos urbanos y estrategias socioculturales en la construcción del sen- tido de pertenencia y del territorio en la ciudad de México, financiado por el Conacyt con la clave 164563 del Fondo Sectorial de Investigación para la Educación (sep-Conacyt). 2 Profesora asociada de la licenciatura en Geografía Humana, uam-i 303 Adriana aguayo ayala mediante esquemas de inversión pública-privada. Estas políticas han generado un modelo de desarrollo urbano caracterizado por la fragmentación, privatización y segregación espacial. Para desarrollar nuestro argumento haremos un recorrido por la historia de la reorganización territorial de la ciudad de Mé- xico y ofreceremos algunos datos que revelan los principales cambios que ésta experimentó en el siglo pasado. Posterior- mente nos centraremos en la descripción de los proyectos de renovación del Centro Histórico y de reconversión de Santa Fe (de basurero a zona financiera), subrayando que una tenden- cia del modelo urbano neoliberal es la fragmentación espacial y la segregación social. -

Worldwide Panorama on BRT Systems

Worldwide Panorama on BRT systems Manfred Breithaupt Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH 21.06.2012 Seite 1 21.06.2012 Page Seite 2 2 How to tackle the problem with urban transport? REDUCE/AVOID SHIFT IMPROVE Shift to more Improve the energy Reduce or avoid environmentally efficiency of transport travel friendly modes modes and vehicle or the need to travel technology • Integration of • Mode shift to Non- • Low-friction lubricants transport and land- Motorized Transport • Optimal tire pressure use planning • Mode shift to Public • Low Rolling Resistance • Smart logistics Transport Tires concepts • Public Transp. Integration • Speed limits, Eco-Driving • … • Transport Demand (Raising Awareness) Management (TDM) • Shift to alternative fuels • … Capacity Building Reduced Carbon Emissions 21.06.2012 Page Seite 3 3 Corridor Capacity BRT Mixed Regular BRT Cyclists Pedestrians Heavy Rail Traffic Bus Single lane Light Rail Sub-urban Rail double lane (e.g. Hong Kong) (e.g. Mumbai) 2 000 9 000 14 000 17 000 19 000 22 000 45 000 80 000 100 000 Source: Botma & Papendrecht, TU Delft 1991 and own figures 21.06.2012 Page Seite 4 4 The need for BRT . Not advisable and possible for all cities to adopt expensive rail systems . Also many cities are low density and sprawling; cannot support the ridership numbers needed for viable rail operations . Urgent need to offer people an attractive, efficient and cleaner alternative to personal -

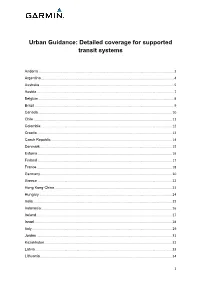

Urban Guidance: Detailed Coverage for Supported Transit Systems

Urban Guidance: Detailed coverage for supported transit systems Andorra .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Argentina ............................................................................................................................................... 4 Australia ................................................................................................................................................. 5 Austria .................................................................................................................................................... 7 Belgium .................................................................................................................................................. 8 Brazil ...................................................................................................................................................... 9 Canada ................................................................................................................................................ 10 Chile ..................................................................................................................................................... 11 Colombia .............................................................................................................................................. 12 Croatia ................................................................................................................................................. -

The Evolution of Cooperative Metropolitan Governance in Mexico City’S Public Transportation

Governing the Metropolis: The evolution of cooperative metropolitan governance in Mexico City’s public transportation By Callida Cenizal B.A. in Latin American Studies Pomona College Claremont, CA (2009) Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in City Planning at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 2015 © Callida Cenizal, all rights reserved The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature of Author ____________________________________________________________ Department of Urban Studies and Planning May 20, 2015 Certified by ___________________________________________________________________ Professor Gabriella Y. Carolini Department of Urban Studies and Planning Thesis Supervisor Accepted by __________________________________________________________________ Professor Dennis Frenchman Chair, MCP Committee Department of Urban Studies and Planning Governing the metropolis: The evolution of cooperative metropolitan governance in Mexico City’s public transportation By Callida Cenizal Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning on May 20, 2015 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master in City Planning Abstract What enables cooperation at the metropolitan scale? This thesis explores public transportation planning in the Mexico City metropolitan area (MCMA) for empirical evidence to better understand what institutional, financial, and political conditions encourage and deter cooperative metropolitan governance. The MCMA, made up of several state-level jurisdictions, predominantly the Federal District (DF) and the State of Mexico (Edomex), continues to expand rapidly, surpassing their jurisdictional capacities and putting pressure on infrastructure like public transit, which carries almost two-thirds of daily traffic. -

Centro De Investigación Y Docencia Economicas, A.C

CENTRO DE INVESTIGACIÓN Y DOCENCIA ECONOMICAS, A.C. EL BOOM DE LAS PLAZAS COMERCIALES EN LA CIUDAD DE MÉXICO TESINA QUE PARA OBTENER EL GRADO DE MAESTRO EN PERIODISMO Y ASUNTOS PÚBLICOS PRESENTA GASPAR RAFAEL CABRERA HERNÁNDEZ DIRECTOR DE LA TESINA: MTRO. CARLOS BRAVO REGIDOR CIUDAD DE MÉXICO JUNIO, 2017 AGRADECIMIENTOS A ALEJANDRO LEGORRETA Y FUNDACIÓN POR SU APOYO PARA CURSAR LA MAESTRÍA DE PERIODISMO Y ASUNTOS PÚBLICOS. A MIS MAESTROS DEL CIDE, POR SU PACIENCIA Y CONSEJOS. A MI FAMILIA Y AMIGOS. Y A MI ESPOSO, RODRIGO CAMPOS. ÍNDICE DE CAPÍTULOS. 1.- PATIOS, TERRAZAS, PASIS Y PARQUES. ....................................................................... 1 2.- UN POCO DE HISTORIA. ..................................................................................................... 3 3.- JORGE GAMBOA DE BUEN Y GRUPO DANHOS. ......................................................... 5 4.- LAS CIFRAS DE LAS DELEGACIONES. .......................................................................... 8 5.- LOS DESARROLLADORES. .............................................................................................. 12 6.- EL CAOS EN EL OASIS. ..................................................................................................... 13 7.- MARGARITA MARTÍNEZ FISHER, DIPUTADA. ......................................................... 16 8.- LA PROCURADURÍA AMBIENTAL. .............................................................................. 19 9.- EL GOBIERNO RESPONDE. ............................................................................................