The Children's Fiction of Russell Hoban: Some Aspects and Themes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Authorities Displaced in the Novels of Russell Hoban

"We make fiction because we are fiction": Authorities Displaced in the Novels of Russell Hoban Lara Dunwell Submitted in fulfilhnent of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English University of Cape Town 1995 University of Cape Town The fmancial assistance of the Centre for Science Development towards this research is hereby acknowledged. Opinions expressed and conclusions arrived at, are those of the author and not necessarily to be attributed to the Centre for Science Development. The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town Acknowledgements: For her continued support and encouragement, I would like to thank my supervisor, Dr Lesley Marx; thanks also to my friends Kate Gillman and Catherine Grylls for their devotion to the onerous task of proofreading. Many others offered much-needed support and motivation: I remember with great appreciation my parents, Mike and Michele, my sister, Coral, Pauline Collins, and Jill Goldberg. I would like to dedicate this thesis to Jonathan Hoffenberg, who loaned his copy of The Medusa Frequency to me in 1989, and never asked me to return it! Finally, I must thank both the University of Cape Town, and the Centre for Science Development; without their financial support, this thesis would not have been written. -

Rising Second Grade

1st into 2nd Grade 2021 Summer Reading List ======================= Prepared by Liz Perry, SFWS Librarian for Class Teacher Deborah LeDean On the threshold of 2nd grade, children possess a burgeoning love of story, an interest cultivated in part by rich Main Lesson content and also by caregivers sharing a love of reading and storytelling at home. This summer, whether read-aloud or read-alone moments are offered as quick intakes of breath in the middle of the day or as restful unfoldings at night before bed, the grade-school library would like to suggest books honoring a variety of interests. The summer reading list includes Picture Books and Read-Aloud chapter-books, both Classic and Contemporary, of animals, adventure, friendship, fantasy, and family life. Included here are also Fairy and Folk Tales, followed by the Alphabet Books; while traditional in scope, they build on the 1st grader’s recent acquisition of letters and their sounds—even proficient readers can revisit these. Children can advance to Early Chapter Books (look for series such as Stepping Stones, Puffin Chapters, Harper Trophy), often housed on a separate carousel from older fiction. Recent Award-Winning Picture Books ● Alfie: (The Turtle that Disappeared), by Thyra Heder (2017). Nia loves Alfie, her pet turtle. But he’s not very soft, he doesn’t do tricks, and he’s pretty quiet. Sometimes she forgets he’s even there! That is until the night before Nia’s seventh birthday, when nAlfie disappears! Then, in an innovative switch in point of view, we hear Alfie’s side of the story. -

Kumon's Recommended Reading List

KUMON’S RECOMMENDED READING LIST - Level 7A ~ Level 3A These are read-aloud books to be used by a parent when reading to the student. LEVEL 7A LEVEL 6A LEVEL 5A LEVEL 4A LEVEL 3A Barnyard Banter Hop on Pop Mean Soup Henny Penny A My Name is Alice 1 Denise Fleming 1 Dr. Seuss 1 Betsy Everitt 1 retold by Paul Galdone 1 Jane Bayer Jesse Bear, What Will Each Orange Had Eight Each Peach Pear Plum The Doorbell Rang Alphabears: An ABC Book 2 You Wear? Slices: A Counting Book Janet and Allen Ahlberg 2 2 Pat Hutchins 2 Kathleen Hague 2 Nancy White Carlstrom Paul Giganti Jr. Eating the Alphabet: Fruits What do you do with a Goodnight Moon Bat Jamboree Sea Squares 3 and Vegetables from A to Z kangaroo? Margaret Wise Brown 3 3 3 Kathi Appelt 3 Joy N. Hulme Lois Ehlert Mercer Mayer Here Are My Hands Black? White! Day? Night! The Icky Bug Alphabet Book Curious George Bread and Jam for Frances 4 Bill Martin Jr. and 4 4 4 4 John Archambault Laura Vaccaro Seeger Jerry Pallotta H.A. Rey Russell Hoban I Heard A Little Baa 5 Big Red Barn My Very First Mother Goose Make Way for Ducklings Little Bear Elizabeth MacLeod 5 Margaret Wise Brown 5 edited by Iona Opie 5 Robert McCloskey 5 Else Holmelund Minarik Read Aloud Rhymes for the Noisy Nora A Rainbow of My Own Millions of Cats Lyle, Lyle Crocodile 6 Very Young 6 Rosemary Wells 6 Don Freeman 6 Wanda Gag 6 Bernard Waber collected by Jack Prelutsky Mike Mulligan and His Steam Quick as a Cricket Sheep in a Jeep The Listening Walk Stone Soup 7 Shovel Audrey Wood 7 Nancy Shaw 7 Paul Showers 7 Marcia Brown 7 Virginia Lee Burton Three Little Kittens Silly Sally The Little Red Hen The Three Billy Goats Gruff Ming Lo Moves the Mountain 8 retold by Paul Galdone 8 Audrey Wood 8 retold by Paul Galdone 8 P.C. -

Setting the Scene Program Guide

Program Guide Patti Sinclair Join the fun! It’s a way for libraries to interest to families—on parenting; kid-friendly crafts welcome and encourage families to become regular and projects; parental concerns, such as saving for col- library users by celebrating and showing what they have lege, autism, and home schooling; etc. Here are some to offer. Connecticut librarians Nadine Lipman and other things you can do: Caitlin Augusta initiated the first Take Your Child to the • Create a Welcome poster in several different languages, Library Day on February 4, 2012. This annual celebra- including those spoken by residents in your communi- tion will take place on the first Saturday in February. ty. You can find several examples online when search- Read on for engaging ways to celebrate this day in your ing “welcome poster in different languages.” library. For more information on the program, visit the Take Your Child to the Library homepage at http://www. • Post photos of all library staff around the library. ctlibrarians.org/?page=Take. You can also visit our Pinter- • Decorate a table or the circulation desk where patrons est page at https://www.pinterest.com/upstart/take-your- apply for library cards. If you expect large crowds, child-to-the-library-day/ for additional programming and consider a costumed character or barker to proclaim activity ideas. “Get Your Library Cards Here.” • Invite participants to write their names on die-cut rab- Setting the Scene bit shapes. Hang them from the ceiling. • Provide bookmarks (available from Upstart at Make sure your library is in tip-top shape—clean www.demco.com/goto?BLS188994&ALL0000& and tidy with attractive book and media displays, es=20151214125933138157) as well as handouts, etc. -

Dystopian Language and Thought: the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis Applied to Created Forms of English

DePauw University Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University Student research Student Work 2014 Dystopian Language and Thought: The aS pir- Whorf Hypothesis Applied to Created Forms of English Kristen Fairchild Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.depauw.edu/studentresearch Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Fairchild, Kristen, "Dystopian Language and Thought: The aS pir-Whorf Hypothesis Applied to Created Forms of English" (2014). Student research. Paper 7. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student research by an authorized administrator of Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Dystopian Language and Thought: The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis Applied to Created Forms of English Kristen Fairchild DePauw University Honor Scholar 401-402: Senior Thesis April 11, 2014 2 3 Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge and thank my three committee members for their guidance and encouragement through this process. Additionally, a special thanks to my advisor, Istvan Csicsery-Ronay Ph.D, for all his extra time and support. 4 5 Introduction The genre of science fiction is a haven for the creation of new worlds, universes, and projections of the future. Many versions of the future represent dystopian societies. While the word dystopia often evokes images of hellish landscapes or militarized super-cities, the word dystopia simply implies “a dis-placement of our reality.”1 Dystopias usually originate from social or political conditions of the present. -

Guided Reading Book List

Title Author Level Anno’s Counting Book Mitsumasa Anno A Count and See Tana Hoban A Dig, Dig Leslie Wood A Do You Want to Be My Friend? Eric Carle A Flowers Karen Hoenecke A Growing Colors Bruce McMillan A In My Garden Moria McLean A Look What I Can Do Jose Aruego A Sea Shapes Suse MacDonald A Taking a Walk Rebecca Emberley A What Do Insects Do? S. Canizares & P. Chanko A What Has Wheels? Karen Hoenecke A Getting There Young B Hats Around the World Liza Charlesworth B Have You Seen My Cat? Eric Carle B Have You Seen My Duckling? Nancy Tafuri B Here’s Skipper Lynn Salem & J. Stewart B How Many Fish? Caron Lee Cohen B I Can Help Stan Wilhelm B I Can Write, Can You? Lynn Salem & J. Stewart B Let’s Go Visiting Sue Williams B Look, Look, Look Tana Hoban B Mommy, Where Are You? Ziefert & Boon B Runaway Monkey Lynn Salem & J. Stewart B So Can I Margery Facklam B Sunburn Ann Prokopchak B Thank You Betsey Chessen B Two Points J. Kennedy & A. Eaton B Under the Bed Bruce Larkin B Water/Who Lives in a Tree?/Who Lives in the Arctic Susan Canizares B Title Author Level All Fall Down Brian Wildsmith C Apples Deborah Williams C Bears Bobbie Kalman C Big Long Animal Song Mike Artwell C Brown Bear, Brown Bear What Do You See? Bill Martin C Cats Deborah Williams C I See Monkeys Deborah Williams C I Want a Pet Barbara Gregorich C I Want To Be a Clown Sharon Johnson C Joshua James Likes Trucks Catherine Petrie C Leaves Karen Hoenecke C Looking for Halloween Karen Evans C Monsters Diane Namm C My Kite Deborah Williams C Octopus Goes to School Carolyn Bordelon C One Hunter Pat Hutchins C Pancakes for Breakfast Tomie dePaola C Rain R. -

Illuminating Poe

Illuminating Poe The Reflection of Edgar Allan Poe’s Pictorialism in the Illustrations for the Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades des Doktors der Philosophie beim Fachbereich Sprach-, Literatur- und Medienwissenschaft der Universität Hamburg vorgelegt von Christian Drost aus Brake Hamburg, 2006 Als Dissertation angenommen vom Fachbereich Sprach-, Literatur- und Medienwissenschaft der Universität Hamburg aufgrund der Gutachten von Prof. Dr. Hans Peter Rodenberg und Prof. Dr. Knut Hickethier Hamburg, den 15. Februar 2006 For my parents T a b l e O f C O n T e n T s 1 Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 2 Theoretical and methodical guidelines ................................................................ 5 2.1 Issues of the analysis of text-picture relations ................................................. 5 2.2 Texts and pictures discussed in this study ..................................................... 25 3 The pictorial Poe .......................................................................................... 43 3.1 Poe and the visual arts ............................................................................ 43 3.1.1 Poe’s artistic talent ......................................................................... 46 3.1.2 Poe’s comments on the fine arts ............................................................. 48 3.1.3 Poe’s comments on illustrations ........................................................... -

Best Friends for Frances Free

FREE BEST FRIENDS FOR FRANCES PDF Russell Hoban,Lillian Hoban | 42 pages | 01 Feb 2009 | HarperCollins Publishers Inc | 9780060838034 | English | New York, NY, United States Best Friends for Frances - Russell Hoban - Google книги My little sister purchased the print and Best Friends for Frances versions of this book at the book fair when we were little kids. We read and listened to it incessantly well, we stopped to eat, sleep, and go to school In this book, Frances treats her little sister poorly at first and wont let her play games with her. Frances then gets slighted by Albert and Harold. Frances learns to play with Best Friends for Frances little sister, and Russell Hoban was born in Lansdale, Pennsylvania on February 4, He taught art in New York and Connecticut, and also worked as an advertising copywriter and a freelance illustrator before beginning his career as a writer. He received the John W. He died on December 13 at the age of Lillian Hoban was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on May 18, She also danced professionally in the 's. During her lifetime, she illustrated or wrote more than children's books. Her first Best Friends for Frances was a book she illustrated, Herman the Loser, written by her husband Russell Hoban, and published in She died from heart failure on July 17, at the age of Best Friends for Frances. Russell Hoban. When Albert says that Frances doesn't know enough to play ball, or to accompany him on one of his wandering days, she turns to her little sister Best Friends for Frances as a playmate and they set out on a best friends only outing with no boys allowed. -

Dystopia, Science Fiction, Post-Apocalypse

Eckart Voigts, Alessandra Boller (eds.) Dystopia, Science Fiction, Post-Apocalypse Classics - New Tendencies - Model Interpretations TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction: The Dystopian Imagination - An Overview 1 ECKART VOIGTS 1. Dystopia and Degeneration: H. G. Wells, The Time Machine (1895) and The War of the Worlds (1898) 13 RICHARD NATE 2. Biopolitical Dystopia: Aldous Huxley, Brave New World (1932) 29 RONJA TRIPP 3. Totalitarian Dystopia: George Orwell, Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) 47 ECKART VOIGTS 4. Anti-Humanist Dystopia: Ray Bradbury, Fahrenheit 451 (1953) 67 RÜDIGER HEINZE 5. Mechanistic Dystopia: E. M. Forster, "The Machine Stops" (1909) and Kurt Vonnegut, Player Piano (1952) 85 NILS WILKINSON AND ECKART VOIGTS 6. Dystopian Violence: A Clockwork Orange (Anthony Burgess 1962/ Stanley Kubrick 1971) 103 RENATE BROSCH 7. Dystopian Androids: Philip K. Dick, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1968) and Ridley Scott, Blade Runner (1982) 121 CHRISTOPH HOUSWITSCHKA 8. Surrealist Dystopia: J. G. Ballard, The Atrocity Exhibition (1970) 139 RAIMUND BORGMEIER 9. Feminist Utopia/Dystopia: Joanna Russ, The Female Man (1975) and Marge Piercy, Woman on the Edge ofTime (1976) 155 JEANNE CORTIEL 10. Ambiguous Utopia: Ursula K. Le Guin, The Dispossessed (1974) 171 RAIMUND BORGMEIER 11. Postcolonial Dystopia: J. M. Coetzee, Waitingfor the Barbarians (1980) 187 JAN WILM 12. Graphic Dystopia: Watchmen (Moore/Gibbons, 1986-1987) and Vfor Vendetta (Moore/Lloyd, 1982-1989) 201 DIRK AND MARIE VANDERBEKE 13. Cyberpunk and Dystopia: William Gibson, Neuromancer (1984) 221 LARS SCHMEINK 14. Religious Dystopia: Margaret Atwood, The Handmaid's Tale (1985) and its Film Adaptation (Schlöndorff/Pinter, 1990) 237 KERSTIN SCHMIDT 15. Posthuman Dystopia/Critical Dystopia: Octavia E. -

![The Best Children's Books of the Year [2018 Edition]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8879/the-best-childrens-books-of-the-year-2018-edition-2288879.webp)

The Best Children's Books of the Year [2018 Edition]

Bank Street College of Education Educate The Center for Children's Literature 4-6-2018 The Best Children's Books of the Year [2018 edition] Bank Street College of Education. Children's Book Committee Follow this and additional works at: https://educate.bankstreet.edu/ccl Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Bank Street College of Education. Children's Book Committee (2018). The Best Children's Books of the Year [2018 edition]. Bank Street College of Education. Retrieved from https://educate.bankstreet.edu/ccl/ 7 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by Educate. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Center for Children's Literature by an authorized administrator of Educate. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Best Children’s Books of the Year 2018 Edition Books Published in 2017 BANK STREET COLLEGE OF EDUCATION THE BEST CHILDREN’S BOOKS OF THE YEAR 2018 EDITION OFBOOKS THE PUBLISHED YEAR IN 2017 SELECTED BY THE CHILDREN’S BOOK COMMITTEE THE CHILDREN’S BOOK COMMITTEE Jina Miharu Accardo Ann Levine Marilyn Ackerman Elizabeth (Liz) Levy Rita Auerbach Muriel Mandell Alice Belgray Roberta Mitchell Sheila Browning Barbara Morris Allie Bruce Caitlyn Morrissey Christie Clark Karina Otoya-Knapp Mary Clark Kathryn Payne Deb Cohen Susan Pine Linda Colarusso Jaïra Placide Ayanna Coleman Ellen Rappaport Carmen Colón Martha Rosen Becky Eisenberg Elizabeth C. Segal Gillian Engberg Dale Singer Margery Fisher Susan Stires Helen Freidus Hadassah Tannor Dee Gantz Jane Thompson Alex Grannis Margaret Tice Melinda Greenblatt Morika Tsujimura Linda Greengrass Leslie Wagner Todd Jackson Cynthia Weill Andee Jorisch Rivka Widerman Mollie Welsh Kruger Shara Zaval Patricia Lakin Todd Zinn Caren Leslie MEMBERS EMERITI Margaret Cooper Lisa Von Drasek MEMBERS ON LEAVE OR AT LARGE Beryl Bresgi Laurent Linn TIPS FOR PARENTS • Share your enjoyment of books with your child. -

The Enchanted Hour

THE ENCHANTED HOUR THE MIRACULOUS POWER OF READING ALOUD IN THE AGE OF DISTRACTION MEGHAN COX GURDON HARPER An Imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers the enchanted hour. Copyright © 2019 by Meghan Cox Gurdon. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address HarperCollins Publishers, 195 Broadway, New York, NY 10007. HarperCollins books may be purchased for educational, business, or sales promotional use. For information, please email the Special Markets Department at [email protected]. first edition Designed by Fritz Metsch Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data has been applied for. ISBN 978-0-06-256281-4 19 20 21 22 23 lsc 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 READ- ALOUD BOOKS MENTIONED IN THE ENCHANTEDr HOUR All highly recommended! 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, by Jules Verne Abel’s Island, by William Steig The Absolutely True Diary of a Part- Time Indian, by Sherman Alexie Adam of the Road, by Elizabeth Gray, illustrated by Robert Lawson The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, by Mark Twain Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, by Lewis Carroll, illustrated by John Tenniel The Amazing Bone, by William Steig Andrew’s Loose Tooth, by Robert Munsch Around the World with Ant and Bee, by Angela Banner Art & Max, by David Wiesner Art Up Close, by Claire d’Harcourt The BabyLit Series, by Jennifer Adams, illustrated by Alison Oliver -

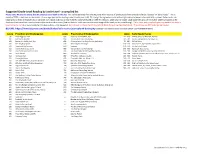

Level Reading by Lexile Level - a Compiled List Please Note: We Are Not Saying That We Endorse Every Book on This List

Suggested Grade-Level Reading by Lexile Level - a compiled list Please note: We are not saying that we endorse every book on this list. ThIs Is a lIst gathered from the ASCI and other sources of books people have consIdered to be "classIcs" or "good reads." ThIs Is merely a TOOL to help you, as the parent, choose age approprIate readIng materIal wIth your chIld. PK through Young reader books wIth a hIgh LexIle are meant to be read wIth a parent. SerIes books can range greatly, check the specIfic book on LexIle.com. Books wIth two or more LexIles noted are based on dIfferent versIons, generally, the longer unabrIdged versIons are the hIgher LexIle compared to the shortened, and some[mes modernIzed and/or condensed versIons. (You can look on LexIle.com for the cover Image of the book you are consIderIng). **Also note: not every book you may want to consIder Is listed on Lexile.com (I.e. many books by ChrIs[an authors, unfortunately). Don't forget to check the BJU Soundforth Book lIst wIth LexIles (See below). Those books are NOT Included on thIs lIst. BJU URL: hps://www.bjupress.com/books/lexiles/lexile-scores-journeyforth-books.php (Clickable Link can be found on our school website under SUMMER READING). Lexile Preschool and Kindergarten Lexile Preschool and Kindergarten Lexile Early Reader Series 30 Green Eggs and Ham 600 Corduroy, by: Freeman, Don BR - 510 ClIfford SerIes, by: BrIdwell, Norman 80 Are You my Mother? 650 You Can Do It!, by: Tony Dungy BR - 760 CurIous George SerIes, by: Rey, H.