STUI'ies Conlederadon Grorrp of Ganadian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Solving the “Indian Problem”

© 2011 D‟Arcy Rheault Solving the “Indian Problem” Assimilation Laws, Practices & Indian Residential Schools D’Arcy Rheault 1842 1844 The 1910 “History of Canada” text book for Ontario Public - The Bagot Commission report (named for Sir Schools taught young Canadians that: Charles Bagot, Governor General of British North America) proposed federally run Indian residential “All Indians were superstitious, having strange ideas about schools as a good tool for separating children from their nature. They thought that birds, beasts...were like men. Thus parents and forcing Aboriginal peoples away from their an Indian has been known to make a long speech of apology to a wounded bear. Such were the people whom the pioneers traditional life. It also mandated that individuals carry of our own race found lording it over the North American only one legal status (e.g., Indian or citizen) thus continent – this untamed savage of the forest who could not disenfranchising most Indian and Métis people in bring himself to submit to the restraints of European life.” Canada by forcing British citizenship upon them and completely erasing tribal identity and nationality.. First missionary operated schools established near Indian Affairs Superintendent, P. G. Anderson, in 1846, Quebec City, 1620-1629 at the General Council of Indian Chiefs and Principle Men in Orillia, Ontario stated “... In 1830 jurisdiction over "Indian" matters was it is because you do not feel, or transferred from the military authorities to the civilian know the value of education; you governors of both Lower and Upper Canada. would not give up your idle roving habits, to enable your children to 1831 , Mohawk Indian Residential School opens in receive instruction. -

Duncan Campbell Scott - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Duncan Campbell Scott - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Duncan Campbell Scott(2 August 1862 – 19 December 1947) Duncan Campbell Scott was a Canadian poet and prose writer. With <a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/charles-g-d-roberts/">Charles G.D. Roberts</a>, <a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/bliss-carman/">Bliss Carman</a> and <a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/archibald- lampman/">Archibald Lampman</a>, he is classed as one of Canada's Confederation Poets. Scott was also a Canadian lifetime civil servant who served as deputy superintendent of the Department of Indian Affairs from 1913 to 1932, and is "best known" today for "advocating the assimilation of Canada’s First Nations peoples" in that capacity. <b>Life</b> Scott was born in Ottawa, Ontario, the son of Rev. William Scott and Janet MacCallum. He was educated at Stanstead Wesleyan Academy. Early in life, he became an accomplished pianist. Scott wanted to be a doctor, but family finances were precarious, so in 1879 he joined the federal civil service. As the story goes, "William Scott might not have money [but] he had connections in high places. Among his acquaintances was the prime minister, Sir John A. Macdonald, who agreed to meet with Duncan. As chance would have it, when Duncan arrived for his interview, the prime minister had a memo on his desk from the Indian Branch of the Department of the Interior asking for a temporary copying clerk. Making a quick decision while the serious young applicant waited in front of him, Macdonald wrote across the request: 'Approved. -

Dr. Peter Henderson Bryce: a Story of Courage July 2016

Dr. Peter Henderson Bryce: A Story of Courage July 2016 conditions within the schools and the incredible number of child deaths Introduction (Milloy, 1999). After inspecting these schools, Dr. Bryce wrote his 1907 “Report on the Dr. Peter Henderson Bryce was a Canadian doctor and a leader in the Indian Schools of Manitoba and the Northwest Territories” which is field of Public Health at the turn of the 20th century. He wrote Canada’s commonly known as “The Bryce Report”. Dr. Bryce used a survey to first Health Code for the province of Ontario in 1884. He later served as gather information from school principals about the health history of president of the American Public Health Association and was a founding children in these schools, and he reported: member of the Canadian Public Health Association (FNCFCS, 2016). Dr. Bryce was also a member of the Canadian Association for the It suffices for us to know… that of a total of 1,537 pupils reported upon Prevention of Tuberculosis, which was his area of expertise (Truth and nearly 25 per cent are dead, of one school with an absolutely accurate Reconciliation Commission, 2015). Today, 100 years after his career as statement, 69 per cent of ex-pupils are dead, and that everywhere the a doctor, Dr. Peter Henderson Bryce is most recognized for his almost invariable cause of death given is tuberculosis (Bryce, 1907, persistence in advocating for better health conditions for Aboriginal p.18). children living in Indian Residential Schools (Bryce, 2012). Further evidence from Dr. Bryce’s inspections suggested that the In 1904, after years of work in Public Health, Dr. -

Frederick George Scott - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Frederick George Scott - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Frederick George Scott(7 April 1861 – 19 January 1944) Frederick George Scott was a Canadian poet and author, known as the Poet of the Laurentians. He is sometimes associated with Canada's Confederation Poets, a group that included <a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/sir-charles-gd- roberts/">Charles G.D. Roberts</a> , <a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/bliss-william-carman/">Bliss William Carman</a>, <a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/archibald- lampman/">Archibald Lampman</a>, and <a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/duncan-campbell-scott/"> Duncan Campbell Scott</a> . Scott published 13 books of Christian and patriotic poetry. Scott was a British imperialist who wrote many hymns to the British Empire—eulogizing his country's roles in the Boer Wars and World War I. Many of his poems use the natural world symbolically to convey deeper spiritual meaning. Frederick George Scott was the father of poet F. R. Scott. <b>Life</b> Frederick George Scott was born 7 April 1861 in Montreal, Canada. He received a B.A. from Bishop's College, Lennoxville, Quebec, in 1881, and an M.A. in 1884. He studied theology at King's College, London in 1882, but was refused ordination in the Anglican Church of Canada for his Anglo-Catholic beliefs. In 1884 he became a deacon. In 1886 he was ordained an Anglican priest at Coggeshall, Essex. He served first at Drummondville, Quebec, and then in Quebec City, where he became rector of St. -

Sustaining Cultural Genocide—A Look at Indigenous Children in Non-Indigenous Placement and the Place of Judicial Decision Making—A Canadian Example

laws Commentary Sustaining Cultural Genocide—A Look at Indigenous Children in Non-Indigenous Placement and the Place of Judicial Decision Making—A Canadian Example Peter Choate 1,* , Roy Bear Chief 1, Desi Lindstrom 2 and Brandy CrazyBull 2 1 Department of Child Studies and Social Work, Mount Royal University, 4825 Mount Royal Gate SW, Calgary, AB T3E 6K6, Canada; [email protected] 2 Faculty of Social Work, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB T2N 1N4, Canada; [email protected] (D.L.); [email protected] (B.C.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The Truth and Reconciliation Commission has called upon Canada to engage in a process of reconciliation with the Indigenous peoples of Canada. Child Welfare is a specific focus of their Calls to Action. In this article, we look at the methods in which discontinuing colonization means challenging legal precedents as well as the types of evidence presented. A prime example is the ongoing deference to the Supreme Court of Canada decision in Racine v Woods which imposes Euro- centric understandings of attachment theory, which is further entrenched through the neurobiological view of raising children. There are competing forces observed in the Ontario decision on the Sixties Scoop, Brown v Canada, which has detailed the harm inflicted when colonial focused assimilation is at the heart of child welfare practice. The carillon of change is also heard in a series of decisions from the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal in response to complaints from the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada and the Assembly of First Nations regarding systemic bias in Citation: Choate, Peter, Roy Bear child welfare services for First Nations children living on reserves. -

A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Arts of Ottawa University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts

"POET OF THE MIST" A CRITICAL ESTIMATION OF THE POSITION OF WILLIAM WILFRED CAMPBELL IN CANADIAN LITERATURE. by MARGARET EVELYN COULBY A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of Arts of Ottawa University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. March 1, 1950. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. " Ottawa UMI Number: EC56059 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI UMI Microform EC56059 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 "POET OF THE MIST" A CRITICAL ESTIMATION OF THE POSITION OF WILLIAM WILFRED CAMPBELL IN CANADIAN LITERATURE. i PREFACE I wish to acknowledge the very great assistance given to me in this work by Mrs. Faith Malloch, of Rockliffe, daughter of the late William Wilfred Campbell, who lent me her unpublished manuscript, eighty-nine pages in length, containing biographical material on the poet's life, letters back and forth between England and Canada and Scotland from Campbell, his friends and daughters, and it also con tained much information about his friends and their influence upon him, I profited also by talking with Colonel Basil Campbell of Ottawa, Campbell's only son. -

Reconciling History Tour

Reconciling History Tour For over a century, until 1996, the Canadian Government removed at least 150,000 Indigenous children from their families to place them in Indian Residential Schools created by itself and run by Christian churches. Thousands died of disease, neglect, or mishap; many suffered physical, spiritual and sexual abuse. In 2008, Survivors forced an apology from the Prime Minister, “for failing them so profoundly.” In 2015, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) called the schools “cultural genocide.” Beginning in 2014, Beechwood Cemetery, Funeral, and Cremation Services and the Beechwood Cemetery Foundation have collaborated with the Indigenous community to create the Reconciling History program. Beechwood has partnered with the First Nations Child & Family Caring Society and KAIROS Canada. With the ultimate goal of education and awareness, Beechwood strives to show both sides of history by not excluding the impact many prominent Canadians buried in the grounds had on the Indigenous community. Choosing rather to highlight both their achievements and their short comings to provide a rounded view of history. The Reconciling History program aims to foster respect and healing through education. The Reconciling History Tour focuses specifically on those who were involved with the Indigenous Community. Those like Dr. Peter Henderson Bryce; who while working at Indian Affairs documented the health crisis in the Residential school system, and Nicolas Flood Davin who wrote the report used as the foundation for creating the residential schools. 1. Dr. Peter Henderson Bryce (August 17, 1853 – January 15, 1932) served as the first secretary of the Provincial Board of Health of Ontario from 1882 to 1904, when he was appointed the Chief Medical Officer of the federal Department of Immigration. -

“Publica(C)Tion”: E. Pauline Johnson's Publishing Venues and Their Contemporary Significance

“Publica(c)tion”: E. Pauline Johnson’s Publishing Venues and their Contemporary Significance SABINE MILZ ORN IN 1861 as the daughter of the Englishwoman Emily Howells and the Mohawk chief and government interpreter George B Johnson of the Six Nations Reserve, Emily Pauline Johnson was to become one of Canada’s most popular and successful poets and platform entertainers of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Today, many Aboriginal writers honour her as the first Aboriginal woman to write in English about Aboriginal issues in poetry and fiction. According to the Mohawk writer Beth Brant, “Pauline Johnson began a movement that has proved unstoppable in its momentum — the movement of First Nations women to write down our stories of history, of revolution, of sorrow, of love” (5). Brant sees Johnson as “a spiritual grandmother to … women writers of the First Nations” (7). In their recent study of Johnson’s life story and career, Paddling Her Own Canoe: The Times and Texts of E. Pauline Johnson (Tekahionwake), Veronica Strong-Boag and Carole Gerson point out that “as a part-Native woman developing an independent career in a socio-political world dominated by powerful White men” (112), Johnson could be ambivalent and self-contradicting, “encompass[ing] the Native storyteller and the European artist, the middle-class lady and the bohemian spirit” (180). Similarly, Janice Fiamengo describes her in “Reconsidering Pauline” as an “ambiguous, boundary-blurring double persona” (175), try- ing to negotiate between the dual imperialist and Aboriginal affiliations of her background and upbringing. It appears that though critics have recently shown an increased interest in Johnson, however, they have not given much attention to the practical-material necessities she had to deal with as an unmarried woman who was trying to make a living with her writing. -

Sound and Silence in Selected Poetry of Duncan Campbell Scott

Lakehead University Knowledge Commons,http://knowledgecommons.lakeheadu.ca Electronic Theses and Dissertations Retrospective theses 1995 Sound and silence in selected poetry of Duncan Campbell Scott Weller, Eric http://knowledgecommons.lakeheadu.ca/handle/2453/1773 Downloaded from Lakehead University, KnowledgeCommons Sound and Silence in Selected Poetry of Duncan Campbell Scott A Thesis presented to the Department of English Lakehead University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Eric Weller May 1995 ProQuest Number: 10611441 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Pro ProQuest 10611441 Published by ProQuest LLC (2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106 - 1346 National Library Biblioth^que nationale 1^1 of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Direction des acquisitions et Bibliographic Services Branch des services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa. Ontario Ottawa (Ontario) K1A0N4 K1A0N4 Your file Votre r6f6rence Our tile Notre r4f6rence The author has granted an L’auteur a accorde une licence irrevocable non-exclusive licence irrevocable et non exclusive allowing the National Library of permettant a la Bibliotheque Canada to reproduce, loan, nationale du Canada de distribute or sell copies of reproduire, preter, distribuer ou his/her thesis by any means and vendre des copies de sa these in any form or format, making de quelque maniere et sous this thesis available to interested quelque forme que ce soit pour persons. -

Indigenous Picton

Northern Voices Indigenous Picton Northern Voices: Indigenous Sun Song, Rita Letendre, 1969 Rita Letendre (1928- ) was born in Drummondville, Quebec, to a father of Abenaki (Algonquian) origin and a Quebecois mother. She was one of the Automatistes – a group of abstract painters led by Paul-Émile Borduas in the 1950s. She used two different abstract styles. This painting is in her early “hard-edged” style. https://www.thestar.com/entertainment/visualarts/2017/07/08/rita-letendre-against-the-dying-of- the-light.html The painting serves to introduce us to Canada’s indigenous peoples. Every bit as talented as the Europeans who colonized their land. Canada is home to many different indigenous cultures. 1 Northern Voices Indigenous Picton Aboriginal peoples in Canada total 1.7 million people, or 5% of the national population 35 million. Of these about 1 million are First Nations, 600 thousand are Métis and 65 thousand are Inuit. Of the First Nations the most populous group is the Cree (600 thousand), whose territory extends from the Northern Quebec and Ontario into the plains. This shows a Shaman’s Charm from the Tsimshian culture in British Columbia). Made from bone and abalone shell it shows elements of raven and of man. Indigenous religions are varied in their detail, but share some common features. Most important is the consciousness of being one with all the world. Many indigenous people have the idea of a Transformer or Trickster who causes things to happen. Among the Ojibwe the trickster was the shapeshifter Nanabush or Nanabozho who often showed up as a rabbit; on the west coast the trickster often took the form of a raven. -

13 Conclusions

Volume 1 - Looking Forward Looking Back PART TWO False Assumptions and a Failed Relationship Chapter 13 - Conclusions 13 Conclusions I want to get rid of the Indian problem. I do not think as a matter of fact, that the country ought to continuously protect a class of people who are able to stand alone... Our objective is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic and there is no Indian question, and no Indian Department, that is the whole object of this Bill.1 RARELY HAVE THE PREVAILING assumptions underlying Canadian policy with regard to Aboriginal peoples been stated so graphically and so brutally. These words were spoken in 1920 by Duncan Campbell Scott, deputy superintendent general of Indian affairs, before a special parliamentary committee established to examine his proposals for amending the enfranchisement provisions of the Indian Act. This statement, redolent of ethnocentric triumphalism, was rooted in nineteenth-century Canadian assumptions about the lesser place of Aboriginal peoples in Canada. Far from provoking fervent and principled opposition to the assimilationist foundation of his testimony, Scott's statements were generally accepted as the conventional wisdom in Aboriginal matters. Any dispute was over the details of his compulsory enfranchisement proposals, not over the moral legitimacy of assimilation as the principle guiding relations between the federal government and Aboriginal peoples. That a Canadian official could speak such words before the representatives -

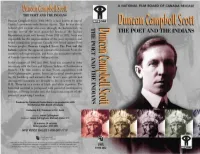

The Poet and the Indians

A NATIONAL FILM BOARD OF CANADA RELEASE THE POET AND THE INDIANS Duncan Campbell Scott (1862-1947) is best known as one of NFBETTj Canada's prominent early literary figures. That he was also a federal civil servant who rose through the bureaucracy to become one of the most powerful beads of the Indian THE POET AND THE INDIANS Department, is not well known. From 1913 to 1932. Scott was responsible tor the implementation of the most repressive and brutal assimilation programs Canada ever levied against First Nations peoples, Duncan Campbell Seott: The Poet and llie Indians explores the apparent contradiction between Scott, the sensitive and respected poet, and SeotL the insensitive enforcer of Canada's .most tyrannical Indian policies. In the summers of 1905 and 19M, Scott was assigned lo enter into treaty mlh the Crée.and Ojibway Indians oV Nortawestmi Ontario. The film centres on that Treaty expédition, with Scott's photographs, poetry, letters and journal entries provid- ing the backdrop and narrative flow, Scott's metre private and introspective moments are brought to life on screen by actor R.H. Thomson in a series of black and white vignettes. The historical material is juxtaposed with powerful contemporary footage, offering insight into the long-term impact of this powerful, perplexing Canadian. Produced by Tamarack Productions in co-production with the National Film Board of Canada Featuring R,H. Thomson as D.C. Scott Director: James CuSSmgham Producers: James Cullingham. Michael Allder(NFB) 56 minutes 28 seconds Order number: 9195 002 NFB VIDEO SALES 1-800-267-7710 Efij'J Closed captioned, rxm A decoder is required, video is cleared for e ooni use and publie pâflf&niafK:epfôvidin:ginosntry fee i çatHecâsî or broadost Ji a vi&fation of Canadian vus l Film Board of Câp PO ËlaxàiCG.