Pan and the Confederation Poets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

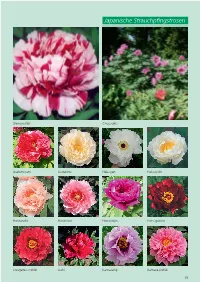

Japanische Strauchpfingstrosen

Japanische Strauchpfingstrosen Shimanishiki Chojuraku Asahiminato Godaishu Hakugan Hakuojishi Hanaasobi Hanakisoi Hanadaijin Hatsugarasu Jitsugetsu-nishiki Jushi Kamatafuji Kamata-nishiki 15 Kao Kokamon Kokuryu-nishiki Luo Yang Hong Meikoho Naniwa-nishiki Renkaku Rimpo Seidai Shim-daijin Shimano-fuji Shinfuso Shin-jitsugetsu Shinshifukujin Shiunden Taiyo Tamafuyo 16 Tamasudare Teni Yachiyotsubaki Yaezakura Yagumo Yatsukajishi Yoshinogawa High Noon Kinkaku Kinko Hakugan Kao 17 Europäische Strauchpfingstrosen Blanche de His Duchesse de Morny Isabelle Riviere Reine Elisabeth Chateau de Courson Jeanne d‘Arc Jacqueline Farvacques Zenobia 18 Rockii-Hybriden Souvenir de Lothar Parlasca Jin Jao Lou Ambrose Congrève Dojean E Lou Si Ezra Pound Fen He Guang Mang Si She Hai Tian E Hei Feng Die Hong Lian Hui He Ice Storm Katrin 19 Lan He Lydia Foote Rockii Ebert Schiewe Shu Sheng Peng Mo Souvenir de Ingo Schiewe Xue Hai Bing Xin Ye Guang Bei Zie Di Jin Feng deutscher Rockii-Sämling Lutea-, Delavayi- und Potaninii-Hybriden Anna Marie Terpsichore 20 Age of Gold Alhambra Alice in Wonderland Amber Moon Angelet Antigone Aphrodite Apricot Arcadia Argonaut Argosy Ariadne Artemis Banquet Black Douglas Black Panther Black Pirate Boreas Brocade Canary 21 Center Stage Chinese Dragon Chromatella Corsair Daedalus Damask Dare Devil Demetra Eldorado Flambeau Gauguin Gold Sovereign Golden Bowl Golden Era Golden Experience Golden Finch Golden Hind Golden Isle Golden Mandarin Golden Vanity 22 Happy Days Harvest Hélène Martin Helios Hephestos Hesperus Icarus Infanta Iphigenia Kronos L‘Espérance L‘Aurore La Lorraine Leda Madame Louis Henry Marchioness Marie Laurencin Mine d‘Or Mystery Narcissus 23 Nike Orion P. delavayi rot P. delavayi orange P. ludlowii P. lutea P. -

Download Download

Too Much Liberty in the Garrison? Closed and Open Spaces in the Canadian Sonnet Timo Müller orthrop Frye’s claim that Canadians developed “a garrison mentality” in the face of a “huge, unthinking, menacing, and formidable” landscape arguably remains the best-known state- Nment on Canadian literature, and one of the most controversial. Since its publication in Frye’s Conclusion to the Literary History of Canada (1965), it has been criticized as mythicizing, homogenizing, and cen- tering on white English Protestant writers (Lecker 284). In recent years the debate has shifted from political critique to historical contextual- ization, foregrounding issues of space, the environment, and Canadian national identity. In a 2009 collection on Frye’s work, Branko Gorjup points to the tension between the environmental determinism of the garrison mentality model and the notion of literature as “autonomous and self-generating” in Frye’s Anatomy of Criticism — a tension he finds replicated in scholarly responses (9; cf. Stacey 84). Adam Carter arrives at a similar conclusion in The Oxford Handbook of Canadian Literature (2016), where he reads Frye’s work against the contemporary debate on Canadian national identity. While Frye often dismissed the idea that the natural or cultural environment had an impact on the literature of a country, Carter notes, his concept of the garrison mentality presup- poses such an impact, as do other important essays Frye published on Canadian poetry (53-55). The analogies Frye draws between literary and spatial formations, and consequently between literary and national environments, derive from his observations both about Canadian literature and about genre traditions that reach beyond Canadian national boundaries. -

Solving the “Indian Problem”

© 2011 D‟Arcy Rheault Solving the “Indian Problem” Assimilation Laws, Practices & Indian Residential Schools D’Arcy Rheault 1842 1844 The 1910 “History of Canada” text book for Ontario Public - The Bagot Commission report (named for Sir Schools taught young Canadians that: Charles Bagot, Governor General of British North America) proposed federally run Indian residential “All Indians were superstitious, having strange ideas about schools as a good tool for separating children from their nature. They thought that birds, beasts...were like men. Thus parents and forcing Aboriginal peoples away from their an Indian has been known to make a long speech of apology to a wounded bear. Such were the people whom the pioneers traditional life. It also mandated that individuals carry of our own race found lording it over the North American only one legal status (e.g., Indian or citizen) thus continent – this untamed savage of the forest who could not disenfranchising most Indian and Métis people in bring himself to submit to the restraints of European life.” Canada by forcing British citizenship upon them and completely erasing tribal identity and nationality.. First missionary operated schools established near Indian Affairs Superintendent, P. G. Anderson, in 1846, Quebec City, 1620-1629 at the General Council of Indian Chiefs and Principle Men in Orillia, Ontario stated “... In 1830 jurisdiction over "Indian" matters was it is because you do not feel, or transferred from the military authorities to the civilian know the value of education; you governors of both Lower and Upper Canada. would not give up your idle roving habits, to enable your children to 1831 , Mohawk Indian Residential School opens in receive instruction. -

Duncan Campbell Scott - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Duncan Campbell Scott - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Duncan Campbell Scott(2 August 1862 – 19 December 1947) Duncan Campbell Scott was a Canadian poet and prose writer. With <a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/charles-g-d-roberts/">Charles G.D. Roberts</a>, <a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/bliss-carman/">Bliss Carman</a> and <a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/archibald- lampman/">Archibald Lampman</a>, he is classed as one of Canada's Confederation Poets. Scott was also a Canadian lifetime civil servant who served as deputy superintendent of the Department of Indian Affairs from 1913 to 1932, and is "best known" today for "advocating the assimilation of Canada’s First Nations peoples" in that capacity. <b>Life</b> Scott was born in Ottawa, Ontario, the son of Rev. William Scott and Janet MacCallum. He was educated at Stanstead Wesleyan Academy. Early in life, he became an accomplished pianist. Scott wanted to be a doctor, but family finances were precarious, so in 1879 he joined the federal civil service. As the story goes, "William Scott might not have money [but] he had connections in high places. Among his acquaintances was the prime minister, Sir John A. Macdonald, who agreed to meet with Duncan. As chance would have it, when Duncan arrived for his interview, the prime minister had a memo on his desk from the Indian Branch of the Department of the Interior asking for a temporary copying clerk. Making a quick decision while the serious young applicant waited in front of him, Macdonald wrote across the request: 'Approved. -

Tammuz Pan and Christ Otes on a Typical Case of Myth-Transference

TA MMU! PA N A N D C H R IST O TE S O N A T! PIC AL C AS E O F M! TH - TR ANS FE R E NC E AND DE VE L O PME NT B! WILFR E D H SC HO FF . TO G E THE R WIT H A BR IE F IL L USTR ATE D A R TIC L E O N “ PA N T H E R U STIC ” B! PAU L C AR US “ " ' u n wr a p n on m s on u cou n r , s n p r n u n n , 191 2 CHIC AGO THE O PE N CO URT PUBLISHING CO MPAN! 19 12 THE FA N F PRAXIT L U O E ES. a n t Fr ticpiccc o The O pen C ourt. TH E O PE N C O U RT A MO N TH L! MA GA! IN E Devoted to th e Sci en ce of Religion. th e Relig ion of Science. and t he Exten si on of th e Religi on Periiu nen t Idea . M R 1 12 . V XX . P 6 6 O L. VI o S T B ( N . E E E , 9 NO 7 Cepyricht by The O pen Court Publishing Gumm y, TA MM ! A A D HRI T U , P N N C S . NO TES O N A T! PIC AL C ASE O F M! TH-TRANSFERENC E AND L DEVE O PMENT. W D H H FF. -

Dr. Peter Henderson Bryce: a Story of Courage July 2016

Dr. Peter Henderson Bryce: A Story of Courage July 2016 conditions within the schools and the incredible number of child deaths Introduction (Milloy, 1999). After inspecting these schools, Dr. Bryce wrote his 1907 “Report on the Dr. Peter Henderson Bryce was a Canadian doctor and a leader in the Indian Schools of Manitoba and the Northwest Territories” which is field of Public Health at the turn of the 20th century. He wrote Canada’s commonly known as “The Bryce Report”. Dr. Bryce used a survey to first Health Code for the province of Ontario in 1884. He later served as gather information from school principals about the health history of president of the American Public Health Association and was a founding children in these schools, and he reported: member of the Canadian Public Health Association (FNCFCS, 2016). Dr. Bryce was also a member of the Canadian Association for the It suffices for us to know… that of a total of 1,537 pupils reported upon Prevention of Tuberculosis, which was his area of expertise (Truth and nearly 25 per cent are dead, of one school with an absolutely accurate Reconciliation Commission, 2015). Today, 100 years after his career as statement, 69 per cent of ex-pupils are dead, and that everywhere the a doctor, Dr. Peter Henderson Bryce is most recognized for his almost invariable cause of death given is tuberculosis (Bryce, 1907, persistence in advocating for better health conditions for Aboriginal p.18). children living in Indian Residential Schools (Bryce, 2012). Further evidence from Dr. Bryce’s inspections suggested that the In 1904, after years of work in Public Health, Dr. -

![Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8862/archons-commanders-notice-they-are-not-anlien-parasites-and-then-in-a-mirror-image-of-the-great-emanations-of-the-pleroma-hundreds-of-lesser-angels-438862.webp)

Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels

A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES WATCH THIS IMPORTANT VIDEO UFOs, Aliens, and the Question of Contact MUST-SEE THE OCCULT REASON FOR PSYCHOPATHY Organic Portals: Aliens and Psychopaths KNOWLEDGE THROUGH GNOSIS Boris Mouravieff - GNOSIS IN THE BEGINNING ...1 The Gnostic core belief was a strong dualism: that the world of matter was deadening and inferior to a remote nonphysical home, to which an interior divine spark in most humans aspired to return after death. This led them to an absorption with the Jewish creation myths in Genesis, which they obsessively reinterpreted to formulate allegorical explanations of how humans ended up trapped in the world of matter. The basic Gnostic story, which varied in details from teacher to teacher, was this: In the beginning there was an unknowable, immaterial, and invisible God, sometimes called the Father of All and sometimes by other names. “He” was neither male nor female, and was composed of an implicitly finite amount of a living nonphysical substance. Surrounding this God was a great empty region called the Pleroma (the fullness). Beyond the Pleroma lay empty space. The God acted to fill the Pleroma through a series of emanations, a squeezing off of small portions of his/its nonphysical energetic divine material. In most accounts there are thirty emanations in fifteen complementary pairs, each getting slightly less of the divine material and therefore being slightly weaker. The emanations are called Aeons (eternities) and are mostly named personifications in Greek of abstract ideas. -

Heidi Savage April 2017 Kypris, Aphrodite, Venus, and Puzzles About Belief My Aim in This Paper Is to Show That the Existence Of

Heidi Savage April 2017 Kypris, Aphrodite, Venus, and Puzzles About Belief My aim in this paper is to show that the existence of empty names raise problems for the Millian that go beyond the traditional problems of accounting for their meanings. Specifically, they have implications for Millian strategies for dealing with puzzles about belief. The standard move of positing a referent for a mythical name to avoid the problem of meaning, because of its distinctly Millian motivation, implies that solving puzzles about belief, when they involve empty names, do in fact require reliance on Millianism after all. 1. Introduction The classic puzzle about belief involves a speaker who lacks knowledge of certain linguistic facts, specifically, knowledge that two distinct names refer to one and the same object -- that they are co-referential. Because of this lack of knowledge, it becomes possible for a speaker to maintain conflicting beliefs about the object in question. This becomes puzzling when we consider the idea that co-referential terms ought to be intersubstitutable in all contexts without any change in meaning. But belief puzzles show not only that this is false, but that it can actually lead to attributing contradictory beliefs to a speaker. The question, then, is what underlying assumption is causing the puzzle? The most frequent response has been to simply conclude that co-referentiality does not make for synonymy. And this conclusion, of course, rules out the Millian view of names – that the meaning of a name is its referent. Kripke, however, argues that belief puzzles are independent any particularly Millian assumptions. -

Unit 1 English Canadian Literature

CANADIAN LITERATURE Unit 1 English Canadian Literature Unit 1 A British Immigrant in the Canadian Mosaic Page 1 Prepared by Mrs. Achamma Alex Christian College, Chengannoor Unit 1 B English Canadian Literature Page 20 Prepared by Dr. M. Snehaprabha Guruvayurappan College, Kozhikode Unit 1 C Modern Period Page 49 Prepared by Dr. H. Kalpana Pondicherry University British Immigrants in the Canadian Mosaic Majority of the immigrants who reached Canada with hopes of better living conditions and a bright future were those forced to leave their motherlands due to various reasons. While the Loyalists from the thirteen colonies of America sought to escape from the bad political situation in their country, it was poverty that prompted the Irish and the Scots to migrate to the Canadian soil. The Jews and fluverites were racially persecuted, and this paved the way for their immigration. Canada was a country of great significance to the English, French and other Europeans as they regularly fished off the banks of Newfoundland. The rivalry between England and France in Canada, in the name of colonial expansion was in fact an extension of the on-going war between the two countries on the European mainland. Their colonial rivalry ended with the division of Canada into the English-speaking territory and the French-speaking territory in 1791. The French-Canadians and the English-Canadians have been considered the "Two Founding Races" of Canada (Metcalfe 346). From the anthropological point of view, this classification is erroneous as both these groups come under the Caucasoid sub-population of human species. After the Norman Conquest of Britain in AD 1066 by William, Duke of Normandy, there had been a mixing of English and French populations. -

ECLECTIC DETACHMENT Aspects of Identity in Canadian Poetry

ECLECTIC DETACHMENT Aspects of Identity in Canadian Poetry A. J. M. Smith I,N THE CLOSING PARAGRAPHS of the Introduction to The Oxford Book of Canadian Verse I made an effort to suggest in a phrase that I hoped might be memorable a peculiar advantage that Canadian poets, when they were successful or admirable, seemed to possess and make use of. This, of course, is a risky thing to do, for what one gains in brevity and point may very well be lost in inconclusiveness or in possibilities of misunderstanding. A thesis needs to be demonstrated as well as stated. In this particular case I think the thesis is implicit in the poems assembled in the last third of the book — and here and there in earlier places too. Nevertheless, I would like to develop more fully a point of view that exigencies of space confined me previously merely to stating. The statement itself is derived from a consideration of the characteristics of Canadian poetry in the last decade. The cosmopolitan flavor of much of the poetry of the fifties in Canada derives from the infusion into the modern world of the archetypal patterns of myth and psychology rather than (as in the past) from Christianity or nationalism. After mentioning the names of James Reaney, Anne Wilkinson, Jay Macpherson, and Margaret Avison—those of the Jewish poets Eli Mandel, Irving Layton, and Leonard Cohen might have been added—I went on to say : The themes that engage these writers are not local or even national; they are cos- mopolitan and, indeed, universal. -

Canadian Poets and the Great Tradition

CANADIAN POETS AND THE GREAT TRADITION Sandra Djwa IIN. THE BEGINNING, as Francis Bacon observes, "God Al- mightie first Planted a Garden ... the Greatest Refreshment to the Spirits of Man."1 It is this lost garden of Eden metamorphosed into the Promised Land, the Hesperides, the El Dorado and the Golden Fleece which dominates some of the sixteenth and seventeenth century accounts of the New World reported in Richard Hakluyt's Principal Navigations, Voyages, Trafiques and Discoveries of the English Nation (i 598-1600) and the subsequent Purchas His Pilgrimes (1625). References to what is now Canada are considerably more restrained than are the eulogies to Nova Spania and Virginia; nonetheless there is a faint Edenic strain in the early reports of the first British settlement in the New World. John Guy implemented the first Royal Patent for settlement at Cupar's Cove, Newfoundland in 1610, a settlement inspired by Bacon and supported by King James, who observed that the plantation of this colony was "a matter and action well beseeming a Christian King, to make true use of that which God from the beginning created for mankind" (Purchas, XIX). Sir Richard Whitbourne's "A Relation of the New-found-land" (1618) continues in the same Edenic vein as he describes Newfoundland as "the fruitful wombe of the earth" : Then have you there faire Strawberries red and white, and as faire Raspasse berrie, and Gooseberries, as there be in England; as also multitudes of Bilberries, which are called by some Whortes, and many other delicate Berries (which I cannot name) in great abundance. -

Frederick George Scott - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Frederick George Scott - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Frederick George Scott(7 April 1861 – 19 January 1944) Frederick George Scott was a Canadian poet and author, known as the Poet of the Laurentians. He is sometimes associated with Canada's Confederation Poets, a group that included <a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/sir-charles-gd- roberts/">Charles G.D. Roberts</a> , <a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/bliss-william-carman/">Bliss William Carman</a>, <a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/archibald- lampman/">Archibald Lampman</a>, and <a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/duncan-campbell-scott/"> Duncan Campbell Scott</a> . Scott published 13 books of Christian and patriotic poetry. Scott was a British imperialist who wrote many hymns to the British Empire—eulogizing his country's roles in the Boer Wars and World War I. Many of his poems use the natural world symbolically to convey deeper spiritual meaning. Frederick George Scott was the father of poet F. R. Scott. <b>Life</b> Frederick George Scott was born 7 April 1861 in Montreal, Canada. He received a B.A. from Bishop's College, Lennoxville, Quebec, in 1881, and an M.A. in 1884. He studied theology at King's College, London in 1882, but was refused ordination in the Anglican Church of Canada for his Anglo-Catholic beliefs. In 1884 he became a deacon. In 1886 he was ordained an Anglican priest at Coggeshall, Essex. He served first at Drummondville, Quebec, and then in Quebec City, where he became rector of St.