The Common Good in Global Perspective Mass Media

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Property Valuation

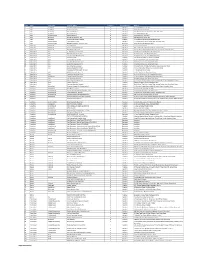

VALUATION LIST OF PROPERTIES - FIRST BATCH (APRIL 2019) S/N Property Id Assessment Name of Property Owner/Occupant Type of Property Use of Property Address of Property Annual Value S/N Property Id Assessment Name of Property Owner/Occupant Type of Property Use of Property Address of Property Annual Value S/N Property Id Assessment Name of Property Owner/Occupant Type of Property Use of Property Address of Property Annual Value Number Number Number 1 0040000278 KRV/TR/J/19/001 0 KOLOME PLAZA SHOPPING MALL/ COMMERCIAL not available, ANGWAN DOKA NEW N448,000.00 108 0030000220 KRV/TR/E/19/013 ALHAJI SHEHU LADY COMFORT SMALL SHOPS COMMERCIAL 0, VINTAGE ESTATE ROAD, CITY N192,000.00 DUNAMIS BOUNDARY,CUSTOM PLAZA NYANYA, ALONG KEFFI ABUJA HAIR COLLEGE MARARABA, MARARABA STREET,MAMMY WAY,BESIDE BENEDAN EXPRESS WAY, NEW NYANYA 109 0030000170 KRV/TR/E/19/002 ALHAJI,SHOPS SHOPS OPPOSITE SMALL SHOPS COMMERCIAL 01, OPPOSITE BOREHOLE OFF N144,000.00 ROAD MARARABA APARTMENT., MARARABA 2 0060000804 KRV/TR/M/19/001 0060000804 MULTI-PURPOSE MIXED USE not available, NOT AVAILABLE, N494,400.00 BOREHOLE SAMAILA MANAGER STREET, BOUNDARY, MASAKA SAMAILA MARARABA MANAGER STREET 216 0010000034 KRV/TR/D/19/001 AYINDA CLINE SHOPPING COMMERCIAL not available, BILL CLINTON N120,000.00 3 0040000154 KRV/TR/A/19/037 101 LOUNGE 101 LOUNGE GUEST HOUSE COMMERCIAL 101, OLD KARU ROAD OPPOSITE N480,000.00 COMPUTER COMPLEX PRIMARY SCHOOL NEW NYA NYA, DUDU COMPANY, MARARABA 110 0040000835 KRV/TR/E/19/0011 ALHAJI UMARU SHOPS CENTER SHOPS COMMERCIAL 0, DAN IYA STREET, MARARABA -

Tuna Fishing and a Review of Payaos in the Philippines

Session 1 - Regional syntheses Tuna fishing and a review of payaos in the Philippines Jonathan O. Dickson*1', Augusto C. Nativiclacl(2) (1) Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources, 860 Arcadia Bldg., Quezon Avenue, Quezon City 3008, Philippines - [email protected] (2) Frabelle Fishing Company, 1051 North Bay Blvd., Navotas, Metro Manila, Philippines Abstract Payao is a traditional concept, which has been successfully commercialized to increase the landings of several species valuable to the country's export and local industries. It has become one of the most important developments in pelagic fishing that significantly contributed to increased tuna production and expansion of purse seine and other fishing gears. The introduction of the payao in tuna fishing in 1975 triggered the rapid development of the tuna and small pelagic fishery. With limited management schemes and strategies, however, unstable tuna and tuna-like species production was experienced in the 1980s and 1990s. In this paper, the evolution and development of the payao with emphasis on the technological aspect are reviewed. The present practices and techniques of payao in various parts of the country, including its structure, ownership, distribution, and fishing operations are discussed. Monitoring results of purse seine/ringnet operations including handline using payao in Celebes Sea and Western Luzon are presented to compare fishing styles and techniques, payao designs and species caught. The fishing gears in various regions of the country for harvesting payao are enumerated and discussed. The inshore and offshore payaos in terms of sea depth, location, designs, fishing methods and catch composi- tion are also compared. Fishing companies and fisherfolk associations involved in payao operation are presented to determine extent of uti- lization and involvement in the municipal and commercial sectors of the fishing industry. -

Obi Patience Igwara ETHNICITY, NATIONALISM and NATION

Obi Patience Igwara ETHNICITY, NATIONALISM AND NATION-BUILDING IN NIGERIA, 1970-1992 Submitted for examination for the degree of Ph.D. London School of Economics and Political Science University of London 1993 UMI Number: U615538 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615538 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 V - x \ - 1^0 r La 2 ABSTRACT This dissertation explores the relationship between ethnicity and nation-building and nationalism in Nigeria. It is argued that ethnicity is not necessarily incompatible with nationalism and nation-building. Ethnicity and nationalism both play a role in nation-state formation. They are each functional to political stability and, therefore, to civil peace and to the ability of individual Nigerians to pursue their non-political goals. Ethnicity is functional to political stability because it provides the basis for political socialization and for popular allegiance to political actors. It provides the framework within which patronage is institutionalized and related to traditional forms of welfare within a state which is itself unable to provide such benefits to its subjects. -

The EERI Oral History Series

CONNECTIONS The EERI Oral History Series Robert E. Wallace CONNECTIONS The EERI Oral History Series Robert E. Wallace Stanley Scott, Interviewer Earthquake Engineering Research Institute Editor: Gail Hynes Shea, Albany, CA ([email protected]) Cover and book design: Laura H. Moger, Moorpark, CA Copyright ©1999 by the Earthquake Engineering Research Institute and the Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to the Earthquake Engineering Research Institute and the Bancroft Library of the University of California at Berkeley. No part may be reproduced, quoted, or transmitted in any form without the written permission of the executive director of the Earthquake Engi- neering Research Institute or the Director of the Bancroft Library of the University of California at Berkeley. Requests for permission to quote for publication should include identification of the specific passages to be quoted, anticipated use of the passages, and identification of the user. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the oral history subject and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or policies of the Earthquake Engineering Research Institute or the University of California. Published by the Earthquake Engineering Research Institute 499 14th Street, Suite 320 Oakland, CA 94612-1934 Tel: (510) 451-0905 Fax: (510) 451-5411 E-Mail: [email protected] Web site: http://www.eeri.org EERI Publication No.: OHS-6 ISBN 0-943198-99-2 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Wallace, R. E. (Robert Earl), 1916- Robert E. Wallace / Stanley Scott, interviewer. p. cm – (Connections: the EERI oral history series ; 7) (EERI publication ; no. -

Agulu Road, Adazi Ani, Anambra State. ANAMBRA 2 AB Microfinance Bank Limited National No

LICENSED MICROFINANCE BANKS (MFBs) IN NIGERIA AS AT SEPTEMBER 30, 2018 S/N Name Category Address State Description 1 AACB Microfinance Bank Limited State Nnewi/ Agulu Road, Adazi Ani, Anambra State. ANAMBRA 2 AB Microfinance Bank Limited National No. 9 Oba Akran Avenue, Ikeja Lagos State. LAGOS 3 ABC Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Mission Road, Okada, Edo State EDO 4 Abestone Microfinance Bank Ltd Unit Commerce House, Beside Government House, Oke Igbein, Abeokuta, Ogun State OGUN 5 Abia State University Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Uturu, Isuikwuato LGA, Abia State ABIA 6 Abigi Microfinance Bank Limited Unit 28, Moborode Odofin Street, Ijebu Waterside, Ogun State OGUN 7 Above Only Microfinance Bank Ltd Unit Benson Idahosa University Campus, Ugbor GRA, Benin EDO Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University Microfinance Bank 8 Limited Unit Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University (ATBU), Yelwa Road, Bauchi BAUCHI 9 Abucoop Microfinance Bank Limited State Plot 251, Millenium Builder's Plaza, Hebert Macaulay Way, Central Business District, Garki, Abuja ABUJA 10 Accion Microfinance Bank Limited National 4th Floor, Elizade Plaza, 322A, Ikorodu Road, Beside LASU Mini Campus, Anthony, Lagos LAGOS 11 ACE Microfinance Bank Limited Unit 3, Daniel Aliyu Street, Kwali, Abuja ABUJA 12 Achina Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Achina Aguata LGA, Anambra State ANAMBRA 13 Active Point Microfinance Bank Limited State 18A Nkemba Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State AKWA IBOM 14 Ada Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Agwada Town, Kokona Local Govt. Area, Nasarawa State NASSARAWA 15 Adazi-Enu -

S/No State City/Town Provider Name Category Coverage Type Address

S/No State City/Town Provider Name Category Coverage Type Address 1 Abia AbaNorth John Okorie Memorial Hospital D Medical 12-14, Akabogu Street, Aba 2 Abia AbaNorth Springs Clinic, Aba D Medical 18, Scotland Crescent, Aba 3 Abia AbaSouth Simeone Hospital D Medical 2/4, Abagana Street, Umuocham, Aba, ABia State. 4 Abia AbaNorth Mendel Hospital D Medical 20, TENANT ROAD, ABA. 5 Abia UmuahiaNorth Obioma Hospital D Medical 21, School Road, Umuahia 6 Abia AbaNorth New Era Hospital Ltd, Aba D Medical 212/215 Azikiwe Road, Aba 7 Abia AbaNorth Living Word Mission Hospital D Medical 7, Umuocham Road, off Aba-Owerri Rd. Aba 8 Abia UmuahiaNorth Uche Medicare Clinic D Medical C 25 World Bank Housing Estate,Umuahia,Abia state 9 Abia UmuahiaSouth MEDPLUS LIMITED - Umuahia Abia C Pharmacy Shop 18, Shoprite Mall Abia State. 10 Adamawa YolaNorth Peace Hospital D Medical 2, Luggere Street, Yola 11 Adamawa YolaNorth Da'ama Specialist Hospital D Medical 70/72, Atiku Abubakar Road, Yola, Adamawa State. 12 Adamawa YolaSouth New Boshang Hospital D Medical Ngurore Road, Karewa G.R.A Extension, Jimeta Yola, Adamawa State. 13 Akwa Ibom Uyo St. Athanasius' Hospital,Ltd D Medical 1,Ufeh Street, Fed H/Estate, Abak Road, Uyo. 14 Akwa Ibom Uyo Mfonabasi Medical Centre D Medical 10, Gibbs Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State 15 Akwa Ibom Uyo Gateway Clinic And Maternity D Medical 15, Okon Essien Lane, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State. 16 Akwa Ibom Uyo Fulcare Hospital C Medical 15B, Ekpanya Street, Uyo Akwa Ibom State. 17 Akwa Ibom Uyo Unwana Family Hospital D Medical 16, Nkemba Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State 18 Akwa Ibom Uyo Good Health Specialist Clinic D Medical 26, Udobio Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State. -

Office of the Auditor-General for the Federation

OFFICE OF THE AUDITOR-GENERAL FOR THE FEDERATION AUDIT HOUSE, PLOT 273 CADASTRAL ZONE AOO, OFF SAMUEL ADEMULEGUN STREET CENTRAL BUSINESS DISTRICT PRIVATE MAIL BAG 128, GARKI ABUJA, NIGERIA LIST OF ACCREDITED FIRMS OF CHARTERED ACCOUNTANTS AS AT 2nd MARCH, 2020 SN Name of Firm Firm's Address City 1 Momoh Usman & Co (Chartered Accountants) Lokoja Kogi State Lokoja 2 Sypher Professional Services (Chartered 28A, Ijaoye Street, Off Jibowu-Yaba Accountants) Onayade Street, Behind ABC Transport 3 NEWSOFT PLC SUITE 409, ADAMAWA ABUJA PLAZA,CENTRAL BUSINESS DISTRICT,ABUJA 4 PATRICK OSHIOBUGIE & Co (Chartered Suite 1010, Block B, Abuja Accountants) Anbeez Plaza 5 Tikon Professionals Chartered Accountants No.2, Iya Agan Lane, Lagos Ebute Metta West, Lagos. 6 Messrs Moses A. Ogidigo and Co No 7 Park Road Zaria Zaria 7 J.O. Aiku & Co Abobiri Street, Off Port Harcourt Harbour Road, Port Harcourt, Rivers State 8 Akewe & Co. Chartered Accountants 26 Moleye Street, off Yaba Herbert Macaulay Way , Alagomeji Yaba, P O Box 138 Yaba Lagos 9 Chijindu Adeyemi & Co Suite A26 Shakir Plaza, Garki Michika Street, Area 11 10 DOXTAX PROFESSIONAL SERVICES D65, CABANA OFFICE ABUJA SUITES, SHERATON HOTE, ABUJA. 11 AKN PROJECTS LIMITED D65, CABANA OFFICE ABUJA SUITES, SHERATON HOTEL, WUSE ZONE 4, ABUJA. 12 KPMG Professional Services KPMG Tower, Bishop Victoria Island Aboyade Cole Street 13 Dox'ix Consults Suite D65, Cabana Suites, Abuja Sheraton Hotel, Abuja 14 Bradley Professional Services 268 Herbert Macaulay Yaba Lagos Way Yaba Lagos 15 AHONSI FELIX CONSULT 29,SAKPONBA ROAD, BENIN CITY OREDO LGA, BENIN CITY 1 16 UDE, IWEKA & CO. -

ECCAIRS Aviation 1.3.0.12 (VL for Attrid

ECCAIRS Aviation 1.3.0.12 Data Definition Standard English Attribute Values ECCAIRS Aviation 1.3.0.12 VL for AttrID: 454 - Geographical areas Africa (Africa) 905 Algeria (Algeria) 5 People's Democratic Republic of Algeria Angola (Angola) 8 Republic of Angola Ascension Island (Ascension Island) 13 Ascension Island (Dependency of the UK overseas territory of Saint Helena) Benin (Benin) 26 Republic of Benin Botswana (Botswana) 30 Republic of Botswana Burkina Faso (Burkina Faso) 38 Burkina Faso Burundi (Burundi) 40 Republic of Burundi Cameroon (Cameroon) 42 Republic of Cameroon Canary Islands (Islas Canarias) (Canary Islands) 44 Autonomous community of the Canary Islands (Spanish archipelago) España (Islas Canarias) El Hierro (El Hierro) 1264 Comunidad Autónoma de Canarias Fuerteventura (Fuerteventura) 1273 Comunidad Autónoma de Canarias Gran Canaria (Gran Canaria) 1265 Comunidad Autónoma de Canarias La Gomera (La Gomera) 1266 Comunidad Autónoma de Canarias La Palma (La Palma) 1267 Comunidad Autónoma de Canarias Lanzarote (Lanzarote) 1274 Comunidad Autónoma de Canarias Tenerife (Tenerife) 1268 Comunidad Autónoma de Canarias Cape Verde (Cape Verde) 46 Republic of Cape Verde Central African Republic (Central African Republic) 49 Central African Republic Chad (Chad) 50 Republic of Chad Comoros (Comoros) 56 Union of the Comoros Congo (Congo) 57 Republic of the Congo. The Republic of the Congo is referred to as Congo-Brazzaville Congo, the Democratic Republic of (Congo, the Democratic Republic of) 309 Democratic Republic of the Congo. The Democratic -

Guidance on Abduction of Crew in Sulu-Celebes Seas

Guidance on Abduction of Crew in the Sulu-Celebes Seas and Waters off Eastern Sabah Produced by: ReCAAP Information Sharing Centre In collaboration with: Philippine Coast Guard Supported by: Asian Shipowners’ Association Singapore Shipping Association (July 2019) Contents Introduction .................................................................................................... 1 Advisory by ReCAAP ISC .............................................................................. 2 Measures adopted by the littoral States in the area ....................................... 4 Modus operandi of past incidents of abduction of crew .................................. 8 Case studies of past incidents ..................................................................... 12 Information on the Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG) ............................................... 14 Annex 1 – Notice to Mariners issued by the Philippines (NOTAM 148-2017 by Philippine Coast Guard)……………………………………………………….15 Annex 2 – Notice to Mariners issued by Malaysia (NOTAM 14 of 2017 by Marine Department of Malaysia, Sabah Region)………………………………17 Annex 3 – Establishment of Recommended Transit Corridor at Moro Gulf and Basilan Strait issued by the Philippine’s Department of Transportation (Memorandum Circular Number 2017-002 dated 31 March 2017)…………..23 <Guidance on Abduction of Crew in the Sulu-Celebes Seas> Introduction This guidance focuses on the incidents of abduction of crew from ships for ransom in the Sulu-Celebes Seas and in the waters off Eastern Sabah. It provides -

CRS Issue Brief for Congress Received Through the CRS Web

Order Code IB98046 CRS Issue Brief for Congress Received through the CRS Web Nigeria in Political Transition Updated June 10, 2003 Theodros Dagne Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress CONTENTS SUMMARY MOST RECENT DEVELOPMENTS BACKGROUND AND ANALYSIS Historical and Political Background Transition to Civilian Rule Elections The 2003 Elections Background Current Economic and Social Conditions Chronology of Recent Events Issues in U.S.-Nigerian Relations Background The United States and the Obasanjo Government CONGRESSIONAL HEARINGS,REPORTS, AND DOCUMENTS FOR ADDITIONAL READING IB98046 06-10-03 Nigeria in Political Transition SUMMARY On June 8, 1998, General Sani Abacha, President Obasanjo met with President Clint- the military leader who took power in Nigeria on and other senior officials in Washington. in 1993, died of a reported heart attack and President Clinton pledged substantial increase was replaced by General Abdulsalam in U.S. assistance to Nigeria. In August 2000, Abubakar. On July 7, 1998, Moshood Abiola, President Clinton paid a state visit to Nigeria. the believed winner of the 1993 presidential He met with President Obasanjo in Abuja and election, also died of a heart attack during a addressed the Nigerian parliament. Several meeting with U.S. officials. General Abubakar new U.S. initiatives were announced, includ- released political prisoners and initiated politi- ing increased support for AIDS prevention cal, economic, and social reforms. He also and treatment programs in Nigeria and en- established a new independent electoral com- hanced trade and commercial development. mission and outlined a schedule for elections and transition to civilian rule, pledging to In May 2001, President Obasanjo met hand over power to an elected civilian govern- with President Bush and other senior officials ment by May 1999. -

Search Our Collections

NOAA Technical Memorandum OAR PMEL-136 SCIENTIFIC AND TECHNICAL ISSUES IN TSUNAMI HAZARD ASSESSMENT OF NUCLEAR POWER PLANT SITES Science Review Working Group Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory Seattle, WA Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory Seattle, WA May 2007 UNITED STATES NATIONAL OCEANIC AND Office of Oceanic and DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE ATMOSPHERIC ADMINISTRATION Atmospheric Research Carlos M. Gutierrez VADM Conrad C. Lautenbacher, Jr. Richard W. Spinrad Secretary Under Secretary for Oceans Assistant Administrator and Atmosphere/Administrator NOTICE from NOAA Mention of a commercial company or product does not constitute an endorsement by NOAA/OAR. Use of information from this publication concerning proprietary products or the tests of such prod- ucts for publicity or advertising purposes is not authorized. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Science Review Working Group: Frank Gonz´alez (Chair), NOAA Center For Tsunami Research, PMEL, Seattle, WA Eddie Bernard, NOAA Center for Tsunami Research, PMEL, Seattle, WA Paula Dunbar, NOAA National Geophysical Data Center, Boulder, CO Eric Geist, USGS Coastal and Marine Geology Division, Menlo Park, CA Bruce Jaffe, USGS Pacific Science Center, Santa Cruz, CA Utku Kˆano˘glu, Middle East Technical University, Ankara, Turkey Jacques Locat, Universit´e Laval, Quebec, Canada Harold Mofjeld, NOAA Center For Tsunami Research, PMEL, Seattle, WA Andrew Moore, Kent State University, Kent, OH Costas Synolakis, USC Tsunami Research Center, Los Angeles, CA Vasily Titov, NOAA Center For Tsunami Research, PMEL, Seattle, WA Robert Weiss, NOAA Center For Tsunami Research, PMEL, Seattle, WA This report should be cited as: Gonz´alez, F.I., E. -

NIGERIA Releases of Political Prisoners - Questions Remain About Past Human Rights Violations

NIGERIA Releases of political prisoners - questions remain about past human rights violations On 4 and 23 March 1999 the Nigerian military government announced the release of most of its remaining political prisoners. They included at least 39 prisoners of conscience and possible prisoners of conscience held in connection with alleged coup plots (see appendix for details of releases). Following the death of former head of state General Sani Abacha on 8 June 1998, the new military government headed by General Abdulsalami Abubakar has gradually released more than 140 political prisoners. Under a new “transition to civil rule” process, elections have been held and a civilian government is due to take over power on 29 May 1999. At least three political prisoners are believed to remain in prison, two of them held since 1990, and the government has not revoked the military decree which allows for the detention without charge or trial of prisoners of conscience. Other military decrees remain in force which have allowed the imprisonment of prisoners of conscience after unfair political trials. Questions remain about the involvement of government officials in past abuses, including the extrajudicial execution of critics, and the need for accountability and a check on impunity. The prisoners released in March 1999 had been imprisoned following secret and grossly unfair trials by Special Military Tribunals. The Tribunals were created by military decree, the Treason and Other Offences (Special Military Tribunal) Decree, No. 1 of 1986, and appointed directly by the military head of state. Presided over by members of the military government, their judgements had to be confirmed or disallowed by the military government.