Buffie Johnson Lucy R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Factory of Visual

ì I PICTURE THE MOST COMPREHENSIVE LINE OF PRODUCTS AND SERVICES "bey FOR THE JEWELRY CRAFTS Carrying IN THE UNITED STATES A Torch For You AND YOU HAVE A GOOD PICTURE OF It's the "Little Torch", featuring the new controllable, méf » SINCE 1923 needle point flame. The Little Torch is a preci- sion engineered, highly versatile instrument capa- devest inc. * ble of doing seemingly impossible tasks with ease. This accurate performer welds an unlimited range of materials (from less than .001" copper to 16 gauge steel, to plastics and ceramics and glass) with incomparable precision. It solders (hard or soft) with amazing versatility, maneuvering easily in the tightest places. The Little Torch brazes even the tiniest components with unsurpassed accuracy, making it ideal for pre- cision bonding of high temp, alloys. It heats any mate- rial to extraordinary temperatures (up to 6300° F.*) and offers an unlimited array of flame settings and sizes. And the Little Torch is safe to use. It's the big answer to any small job. As specialists in the soldering field, Abbey Materials also carries a full line of the most popular hard and soft solders and fluxes. Available to the consumer at manufacturers' low prices. Like we said, Abbey's carrying a torch for you. Little Torch in HANDY KIT - —STARTER SET—$59.95 7 « '.JBv STARTER SET WITH Swest, Inc. (Formerly Southwest Smelting & Refining REGULATORS—$149.95 " | jfc, Co., Inc.) is a major supplier to the jewelry and jewelry PRECISION REGULATORS: crafts fields of tools, supplies and equipment for casting, OXYGEN — $49.50 ^J¡¡r »Br GAS — $49.50 electroplating, soldering, grinding, polishing, cleaning, Complete melting and engraving. -

Art Power : Tactiques Artistiques Et Politiques De L’Identité En Californie (1966-1990) Emilie Blanc

Art Power : tactiques artistiques et politiques de l’identité en Californie (1966-1990) Emilie Blanc To cite this version: Emilie Blanc. Art Power : tactiques artistiques et politiques de l’identité en Californie (1966-1990). Art et histoire de l’art. Université Rennes 2, 2017. Français. NNT : 2017REN20040. tel-01677735 HAL Id: tel-01677735 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01677735 Submitted on 8 Jan 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. THESE / UNIVERSITE RENNES 2 présentée par sous le sceau de l’Université européenne de Bretagne Emilie Blanc pour obtenir le titre de Préparée au sein de l’unité : EA 1279 – Histoire et DOCTEUR DE L’UNIVERSITE RENNES 2 Mention : Histoire et critique des arts critique des arts Ecole doctorale Arts Lettres Langues Thèse soutenue le 15 novembre 2017 Art Power : tactiques devant le jury composé de : Richard CÁNDIDA SMITH artistiques et politiques Professeur, Université de Californie à Berkeley Gildas LE VOGUER de l’identité en Californie Professeur, Université Rennes 2 Caroline ROLLAND-DIAMOND (1966-1990) Professeure, Université Paris Nanterre / rapporteure Evelyne TOUSSAINT Professeure, Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès / rapporteure Elvan ZABUNYAN Volume 1 Professeure, Université Rennes 2 / Directrice de thèse Giovanna ZAPPERI Professeure, Université François Rabelais - Tours Blanc, Emilie. -

2010-2011 Newsletter

Newsletter WILLIAMS G RADUATE PROGRAM IN THE HISTORY OF A RT OFFERED IN COLLABORATION WITH THE CLARK ACADEMIC YEAR 2010–11 Newsletter ••••• 1 1 CLASS OF 1955 MEMORIAL PROFESSOR OF ART MARC GOTLIEB Letter from the Director Greetings from Williamstown! Our New features of the program this past year include an alumni now number well over 400 internship for a Williams graduate student at the High Mu- going back nearly 40 years, and we seum of Art. Many thanks to Michael Shapiro, Philip Verre, hope this newsletter both brings and all the High staff for partnering with us in what promises back memories and informs you to serve as a key plank in our effort to expand opportuni- of our recent efforts to keep the ties for our graduate students in the years to come. We had a thrilling study-trip to Greece last January with the kind program academically healthy and participation of Elizabeth McGowan; coming up we will be indeed second to none. To our substantial community of alumni heading to Paris, Rome, and Naples. An ambitious trajectory we must add the astonishingly rich constellation of art histori- to be sure, and in Rome and Naples in particular we will be ans, conservators, and professionals in related fields that, for a exploring 16th- and 17th-century art—and perhaps some brief period, a summer, or on a permanent basis, make William- sense of Rome from a 19th-century point of view, if I am al- stown and its vicinity their home. The atmosphere we cultivate is lowed to have my way. -

HARD FACTS and SOFT SPECULATION Thierry De Duve

THE STORY OF FOUNTAIN: HARD FACTS AND SOFT SPECULATION Thierry de Duve ABSTRACT Thierry de Duve’s essay is anchored to the one and perhaps only hard fact that we possess regarding the story of Fountain: its photo in The Blind Man No. 2, triply captioned “Fountain by R. Mutt,” “Photograph by Alfred Stieglitz,” and “THE EXHIBIT REFUSED BY THE INDEPENDENTS,” and the editorial on the facing page, titled “The Richard Mutt Case.” He examines what kind of agency is involved in that triple “by,” and revisits Duchamp’s intentions and motivations when he created the fictitious R. Mutt, manipulated Stieglitz, and set a trap to the Independents. De Duve concludes with an invitation to art historians to abandon the “by” questions (attribution, etc.) and to focus on the “from” questions that arise when Fountain is not seen as a work of art so much as the bearer of the news that the art world has radically changed. KEYWORDS, Readymade, Fountain, Independents, Stieglitz, Sanitary pottery Then the smell of wet glue! Mentally I was not spelling art with a capital A. — Beatrice Wood1 No doubt, Marcel Duchamp’s best known and most controversial readymade is a men’s urinal tipped on its side, signed R. Mutt, dated 1917, and titled Fountain. The 2017 centennial of Fountain brought us a harvest of new books and articles on the famous or infamous urinal. I read most of them in the hope of gleaning enough newly verified facts to curtail my natural tendency to speculate. But newly verified facts are few and far between. -

Discover Create Share

9TH ANNUAL UNDERGRADUATE SYMPOSIUM DISCOVER CREATE SHARE 9 AM – 4 PM J . L e a om wre yd nce Walkup Sk nau.edu/symposium DOME FLOOR MAP 32 29 26 23 20 17 14 11 8 3 AGE ST ST 34 5 AGE i i 31 28 25 22 19 16 13 10 7 2 FCB D 33 4 C 30 27 24 21 18 15 12 9 6 1 HHS T 118 T CEFNS 121 111 43 COE CAL HONORS 114 GL 117 38 120 113 110 42 46 53 T T 106 108 116 48 R2 R3 37 HONORS 119 112 109 45 52 41 50 CAL FLOOR i i 105 115 FLOOR 107 47 36 R1 51 49 40 44 T 104 35 UC 39 SBS 130 127 124 T 94 87 80 73 66 103 100 97 90 83 76 69 62 59 56 129 126 123 93 86 79 72 65 i 128 125 122 A 102 99 96 89 82 75 68 61 58 55 B 92 85 78 71 64 STAGE 101 98 95 88 81 74 67 60 57 54 STAGE 91 84 77 70 63 i Volunteers CEFNS Room Judges’ Room Skydome East Concourse ADA Section i CHECK-IN / Main Entrance IWP - Video Gaming Symposium EAST CONCOURSE FCB CEFNS GL POSTER DISPLAY The W.A. Franke College of Business College of Engineering, Forestry, and Natural Science Global Learning Program PRESENTATION STAGE KIOSK POSTER DISPLAY BOARD COE SBS HHS College of Education Social and Behavioral Sciences College of Health and Human Services ROUNDTABLE T DISPLAY TABLE D B 1-130 C A CAL HONORS UC College of Arts and Letters University Honors Program University College i INFORMATION MAP NOT TO SCALE Message from the President Dear Students, Faculty Mentors, and Guests, I am privileged to welcome you to NAU’s ninth annual Undergraduate Symposium. -

Head of a Woman Program Final Digital

HEAD OF A WOMAN Redressing the Parallel Histories of Collaborative Printmaking and the Women’s Movement Presented by Tamarind Institute with support from Frederick Hammersley Foundation Sixty years ago June Wayne, founder of collaborative printmaking over the past sixty years. The rise of Tamarind Lithography Workshop, submitted contemporary printmaking in the 1960s and 1970s runs parallel to the her proposal to the Ford Foundation to burgeoning women’s movement, which no doubt contributed to the establish a model workshop in Los Angeles, steady surge of women printers and printmakers. Head of a Woman brings together an intergenerational roster of artists, printers, scholars, specifically designed to restore the fine and publishers, with the hopes of reflecting on this intertwined history art of lithography. This symposium pays and propelling the industry--and the thinking around prints--forward. tribute to the creative industry that Wayne imagined, and the many remark- Diana Gaston able women who shaped the field of Director, Tamarind Institute 11:00 | THE LONG VIEW: WOMEN IN THE TAMARIND MORNING WORKSHOP AND THEIR CONTINUED IMPACT PRESENTATIONS CHRISTINE ADAMS holds a BFA in printmaking from Arizona State University and received 9:30 | DOORS OPEN her Tamarind Master Printer certificate in May 10:00 | INTRODUCTION 2019. Her printing experience includes positions at the LeRoy Neiman Center for Print Studies at Columbia University and Lower East Side 10:15 | INKED UP: SIXTY YEARS Printshop. Adams is currently a collaborative printer at Universal Limited Art Editions (ULAE) OF COLLABORATIVE WOMEN PRINTMAKERS and a member of the printmaking faculty at Parsons School of Design in New York City. -

Oral History Interview with Rachel Rosenthal

Oral history interview with Rachel Rosenthal Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 General............................................................................................................................. 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 1 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 1 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 2 Container Listing ...................................................................................................... Oral history interview with Rachel Rosenthal AAA.rosent89 Collection Overview Repository: Archives of American Art Title: Oral history interview with Rachel Rosenthal Identifier: AAA.rosent89 Date: 1989 September 2-3 Creator: Rosenthal, Rachel, 1926- (Interviewee) Roth, Moira (Interviewer) Women in the -

Oral History Interview with June Wayne, 1970 August 4-6

Oral history interview with June Wayne, 1970 August 4-6 Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with June Wayne on August 4, 1970. The interview took place in Los Angeles, CA, and was conducted by Paul Cummings for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Interview Tape 1, Side 1 PAUL CUMMINGS: It's August 4 - Paul Cummings talking to June Wayne in her studio. Well, how about some background. You were born in Chicago? JUNE WAYNE: Yes, I was. I understand I was born at the Lying-In Hospital on the Midway in Chicago. Right in the shadow of the University of Chicago. PAUL CUMMINGS: And then you went to Gary, Indiana? JUNE WAYNE: I went to Gary when I was an infant. I don't know whether I was a year old or two years old. I do know that I was back in Chicago by the time I was four or five. So my stay in Gary was very brief. Incidentally, I have memories of Gary, of the steel mills at night, those giant candles with the flutes of fire coming out of the stacks. I also remember very vividly picking black-eyed Susans along the railroad tracks of the Illinois Central in Gary. I must have lived somewhere nearby. My grandmother used to take me for walks along there. I can remember that very significantly. I have lots of memories of Gary. -

Tamarind Homage to Lithography Preface by William S

Tamarind homage to lithography Preface by William S. Lieberman. Introduction by Virginia Allen Author Museum of Modern Art (New York, N.Y.) Date 1969 Publisher Distributed by New York Graphic Society, Greenwich, Conn. Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/1869 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history—from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art Tamarind:Homage to Lithography Tamarind: Homage to Lithography Preface by William S. Lieberman Introduction by Virginia Allen 4- The Tamarind Lithography Workshop has almost single- handedly revived the difficult medium of lithography in the past decade. It has provided not only the materials but also the environment that fosters the delicate collaboration be tween artist and printer. Such an environment and indeed even the materials were almost nonexistent in the United States before June Wayne and the Ford Foundation agreed on the importance of providing them. Since Tama rind opened its doors in 1960 it has provided fellowships for numerous artists and printers, most of whom have con tinued their exploration of lithography after leaving Tama rind. The author describes this unique Workshop and also gives a brief history of lithography in Europe and in the United States. Included is a list which catalogs part of the promised gift to The Museum of Modern Art of the Kleiner, Bell and Company Collection of Tamarind Impressions. The author, Virginia Allen, former curator of Tamarind, is now Assistant to William S. -

Partial Artist List: Nancy Angelo Jerri Allyn Leslie Belt Rita Mae Brown Kathleen Burg Elizabeth Canelake Velene Campbell Carol Chen Judy Chicago Clsuf Michelle T

Doin’ It in Public: Feminism and Art at the Woman’s Building October 1, 2011 – January 28, 2012 Ben Maltz Gallery, Otis College of Art and Design This exhibition presents artwork, graphic design, ephemera, and documentation of work by the artist collectives and individual artists/designers who participated in collaborative projects at the Woman’s Building in Los Angeles between 1973-1991. Artist Collectives/Projects: Ariadne: A Social Network, Feminist Art Workers, Incest Awareness Project, Lesbian Art Project, Mother Art, Natalie Barney Collective, Sisters of Survival, The Waitresses, Chrysalis: A magazine of Women’s Culture, and more. Partial artist list: Nancy Angelo Jerri Allyn Leslie Belt Rita Mae Brown Kathleen Burg Elizabeth Canelake Velene Campbell Carol Chen Judy Chicago Clsuf Michelle T. Clinton Hyunsook Cho Yreina Cervantez Candace Compton Jan Cook Juanita Cynthia Sheila Levrant de Bretteville Johanna Demetrakas Nelvatha Dunbar Mary Beth Edelson Marguerite Elliot Donna Farnsworth Anne Finger Audrey Flack As of 9-27-11 Amani Fliers Nancy Fried Patricia Gaines Josephina Gallardo Diane Gamboa Cristina Gannon Anne Gauldin Cheri Gaulke Anita Green Vanalyne Green Mary Bruns Gonenthal Kirsten Grimstad Chutney Gunderson Berry Brook Hallock Hella Hammid Harmony Hammond Gloria Hajduk Eloise Klein Healy Mary Linn Hughes Annette Hunt Sharon Immergluck Ruth E. Iskin Cyndi Kahn Maria Karras Susan E. King Laurel Klick Deborah Krall Christie Kruse Sheila Levrant de Bretteville Suzanne Lacy Leslie Labowitz-Starus Lili Lakich Linda Lopez Bia -

Eye to I: Self-Portraits from the National Portrait Gallery on View June 12 to September 12

MASTERWORKS SPONSORSHIP OPPORTUNITIES Eye to I: Self-Portraits from the National Portrait Gallery On view June 12 to September 12. Drawing from the National Portrait Gallery’s vast collection, Eye to I will examine how artists in the United States have chosen to portray themselves since the beginning of the last century. The exhibition has been organized by the Smithsonian's National Portrait Gallery, Washington, D.C. and supported in part by Mr. and Mrs. Michael H. Podell. ALBUQUERQUE MUSEUM FOUNDATION To sponsor a MasterWork call Elaine Richardson 505.677.8491 or email [email protected] MASTERWORKS SPONSORSHIP OPPORTUNITIES Featured MasterWorks $1,000 – Pages 1-4 Paintings $500 – Pages 5-16 Prints, Photography, Drawings, and Watercolors $250 – Pages 17-60 ALBUQUERQUE MUSEUM FOUNDATION To sponsor a MasterWork call Elaine Richardson 505.677.8491 or email [email protected] MASTERWORKS FEATURED WORK• $1,000 Robert Rauschenberg 1925 Port Arthur, Texas – 2008 Captiva, Florida Autobiography 1968 offset lithograph National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; the Ruth Bowman and Harry Kahn Twentieth-Century American Self- Portrait Collection NPG.2002.313 ALBUQUERQUE MUSEUM FOUNDATION To sponsor a MasterWork call Elaine Richardson 505.677.8491 or email [email protected] Page 1 MASTERWORKS FEATURED WORK • $1,000 Roger Shimomura born 1939 Seattle, Washington; lives Lawrence, Kansas Shimomura Crossing the Delaware 2010 acrylic on canvas National Portrait Gallery, -

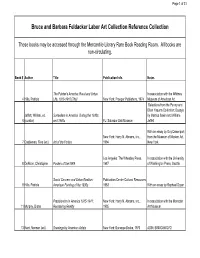

Bruce and Barbara Feldacker Labor Art Collection Reference Collection

Page 1 of 31 Bruce and Barbara Feldacker Labor Art Collection Reference Collection These books may be accessed through the Mercantile Library Rare Book Reading Room. All books are non-circulating. Book # Author Title Publication Info. Notes The Painter's America: Rural and Urban In association with the Whitney 4 Hills, Patricia Life, 1810-1910 [The] New York: Praeger Publishers, 1974 Museum of American Art Selections from the Penny and Elton Yasuna Collection; Essays Jeffett, William, ed. Surrealism in America During the 1930s by Martica Sawin and William 6 (curator) and 1940s FL: Salvador Dali Museum Jeffett With an essay by Guy Davenport; New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., from the Museum of Modern Art, 7 Castleman, Riva (ed.) Art of the Forties 1994 New York Los Angeles: The Wheatley Press, In association with the University 8 DeNoon, Christopher Posters of the WPA 1987 of Washington Press, Seattle Social Concern and Urban Realism: Publication Center Cultural Resources, 9 Hills, Patricia American Painting of the 1930s 1983 With an essay by Raphael Soyer Precisionism in America 1915-1941: New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., In association with the Montclair 11 Murphy, Diana Reordering Reality 1995 Art Museum 13 Kent, Norman (ed.) Drawings by American Artists New York: Bonanza Books, 1970 ASIN: B000G5WO7Q Page 2 of 31 Slatkin, Charles E. and New York: Oxford University Press, 14 Shoolman, Regina Treasury of American Drawings 1947 ASIN: B0006AR778 15 American Art Today National Art Society, 1939 ASIN: B000KNGRSG Eyes on America: The United States as New York: The Studio Publications, Introduction and commentary on 16 Hall, W.S.