Beyond a Woman's Place

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Berthe Morisot

Calgary Sketch Club April and May 2021 Message from the President “It is important to express oneself ... provided the feelings are real and are taken from your own experience.” ~ Berthe Morisot And now warmer weather invites us outside, into the fields and gardens to experience nature, gain an impression, paint a record of our sensations. Welcome to a summer of painting. Whether you take your photos and paint in the studio or make the time to sit amidst the dynamic landscape, get out and experience the real colours, shapes, and shifting light. Your paintings will be the better for having authentic emotional content. This spring we were able to enjoy a club meeting dedicated to Plein Aire painting, a technical painting method that supported the development of the Impressionism move- ment. While some people may be familiar with the men who worked in impressionism, Monet, Manet, Gaugin, and so on, few dwell on the contribution of women painters to the development and furthering of painting your sensations, impressions, and expe- riences. After viewing work by Berthe Morisot, Mary Cassatt, Eva Gonzales, Marie Bracquemond and Lilly Cabot Perry, we see a sizable contribution to the oevre from the depths of meaning and exciting brushwork of these pioneering artists. The social cultural milleau of 1874 Paris, it was difficult for women to find equal footing or even acceptance as artists. And no matter that the art could stand beside that of any con- temporary man or woman, it was sometimes not enough. However, time has allowed a fuller examination of their work and its place in the impressionist canon. -

2010-2011 Newsletter

Newsletter WILLIAMS G RADUATE PROGRAM IN THE HISTORY OF A RT OFFERED IN COLLABORATION WITH THE CLARK ACADEMIC YEAR 2010–11 Newsletter ••••• 1 1 CLASS OF 1955 MEMORIAL PROFESSOR OF ART MARC GOTLIEB Letter from the Director Greetings from Williamstown! Our New features of the program this past year include an alumni now number well over 400 internship for a Williams graduate student at the High Mu- going back nearly 40 years, and we seum of Art. Many thanks to Michael Shapiro, Philip Verre, hope this newsletter both brings and all the High staff for partnering with us in what promises back memories and informs you to serve as a key plank in our effort to expand opportuni- of our recent efforts to keep the ties for our graduate students in the years to come. We had a thrilling study-trip to Greece last January with the kind program academically healthy and participation of Elizabeth McGowan; coming up we will be indeed second to none. To our substantial community of alumni heading to Paris, Rome, and Naples. An ambitious trajectory we must add the astonishingly rich constellation of art histori- to be sure, and in Rome and Naples in particular we will be ans, conservators, and professionals in related fields that, for a exploring 16th- and 17th-century art—and perhaps some brief period, a summer, or on a permanent basis, make William- sense of Rome from a 19th-century point of view, if I am al- stown and its vicinity their home. The atmosphere we cultivate is lowed to have my way. -

HARD FACTS and SOFT SPECULATION Thierry De Duve

THE STORY OF FOUNTAIN: HARD FACTS AND SOFT SPECULATION Thierry de Duve ABSTRACT Thierry de Duve’s essay is anchored to the one and perhaps only hard fact that we possess regarding the story of Fountain: its photo in The Blind Man No. 2, triply captioned “Fountain by R. Mutt,” “Photograph by Alfred Stieglitz,” and “THE EXHIBIT REFUSED BY THE INDEPENDENTS,” and the editorial on the facing page, titled “The Richard Mutt Case.” He examines what kind of agency is involved in that triple “by,” and revisits Duchamp’s intentions and motivations when he created the fictitious R. Mutt, manipulated Stieglitz, and set a trap to the Independents. De Duve concludes with an invitation to art historians to abandon the “by” questions (attribution, etc.) and to focus on the “from” questions that arise when Fountain is not seen as a work of art so much as the bearer of the news that the art world has radically changed. KEYWORDS, Readymade, Fountain, Independents, Stieglitz, Sanitary pottery Then the smell of wet glue! Mentally I was not spelling art with a capital A. — Beatrice Wood1 No doubt, Marcel Duchamp’s best known and most controversial readymade is a men’s urinal tipped on its side, signed R. Mutt, dated 1917, and titled Fountain. The 2017 centennial of Fountain brought us a harvest of new books and articles on the famous or infamous urinal. I read most of them in the hope of gleaning enough newly verified facts to curtail my natural tendency to speculate. But newly verified facts are few and far between. -

American Art New York | November 19, 2019

American Art New York | November 19, 2019 AMERICAN ART | 39 2 | BONHAMS AMERICAN ART | 3 American Art at Bonhams New York Jennifer Jacobsen Director Aaron Anderson Los Angeles Scot Levitt Vice President Kathy Wong Specialist San Francisco Aaron Bastian Director American Art New York | Tuesday November 19, 2019 at 4pm BONHAMS BIDS INQUIRIES ILLUSTRATIONS 580 Madison Avenue +1 (212) 644 9001 Jennifer Jacobsen Front Cover: Lot 15 New York, New York 10022 +1 (212) 644 9009 fax Director Inside Front Cover: Lots 47 and 48 bonhams.com [email protected] +1 (917) 206 1699 Inside Back Cover: Lot 91 [email protected] Back Cover: Lot 14 PREVIEW To bid via the internet please visit Friday, November 15, 10am - 5pm www.bonhams.com/25246 Aaron Anderson Saturday, November 16, 10am - 5pm +1 (917) 206 1616 Sunday, November 17, 12pm - 5pm Please note that bids should be [email protected] Monday, November 18, 10am - 5pm summited no later than 24hrs prior to the sale. New Bidders must REGISTRATION also provide proof of identity when IMPORTANT NOTICE SALE NUMBER: 25246 submitting bids. Failure to do this Please note that all customers, Lots 1 - 101 may result in your bid not being irrespective of any previous processed. activity with Bonhams, are CATALOG: $35 required to complete the Bidder LIVE ONLINE BIDDING IS Registration Form in advance of AUCTIONEER AVAILABLE FOR THIS SALE the sale. The form can be found Rupert Banner - 1325532-DCA Please email bids.us@bonhams. at the back of every catalogue com with “Live bidding” in the and on our website at www. -

Cecilia Beaux: Philadelphia Artist

Cecilia Beaux: PhiladelphiaArtist PUBLISHED SINCE 1877 BY THE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF PENNSYLVANIA - - 2 b ?n1nq CXXIV a 3 Book Reviews OGDEN, Legacy- A Biography ofMoses and Walter Annenberg, by Nelson D. Lankford 419 HEMPHIL, Bowing to Necessity: A History ofManners in America, 1620-1860, by Franklin T. Lambert 421 ST. GEORGE, Conversing by Signs: Poetics of Implication in ColonialNew England Culture, by Margaretta M. Lovell 422 DALZELL and DALZELL, George Washington'sMount Vernon: At Home in Revolutionary America, and GARRETr, ed., LAuTMAN, photog., George Washington'sMount Vernon, and GREENBERG, BucHMAN, photog., George Washington:Architect, by James D. Kornwolf 425 WARREN, ed., The Papersof George Washington.Presidential Series, Vol. 7. December 1790-March 1791, by Patrick J. Furlong 431 MASTROMARNO, WARREN, eds., The Papers of George Washington. PresidentialSeries. Vol. 8: March-September 1791, by Ralph Ketcham 432 ABBOT and LENGEL, eds., The Papersof George Washington. Retirement Series. Vol. 3: September 1798-April 1799. Vol. 4: April-December 1799, by John Ferling 435 LARSON, Daughters ofLight: Quaker Women Preachingand Prophesyingin the Colonies andAbroad, 1700-1775, by Jean R. Soderlund 437 LAMBERT, Inventing the "GreatAwakening," by Timothy D. Hall 439 FORTUNE, Franklinand His Friends:Portraying the Man of Science in Eighteenth-CenturyAmerica, by Brian J. Sullivan 441 NUxOLL and GALLAGHER, The Papers ofRobert Morris, 1781-1784. VoL 9: January 1-October30,1784, by Todd Estes 443 RIGAL, The American Manufactory: Art, Labor, and the World of Things in the Early Republic, by Colleen Terrell 445 SKEEN, Citizen Soldiers in the War of 1812, by Samuel Watson 446 WEEKLEY, The Kingdoms ofEdward Hicks, and FORD, EdwardHicks: Painterof the PeaceableKingdom, by Carol Eaton Sokis 448 GRIFFIN, ed., Beloved Sisters and Loving Friends:Letters from Rebecca Primus ofRoyal Oak, Maryland, andAddie Brown of HartfordConnecticut,1854-1868 by Frances Smith Foster 452 DYER, Secret Yankees: The Union Circle in ConfederateAtlanta, by Jonathan M. -

Emmet, Lydia Field American, 1866 - 1952

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS American Paintings, 1900–1945 Emmet, Lydia Field American, 1866 - 1952 William Merritt Chase, Lydia Field Emmet, 1892, oil on canvas, Brooklyn Museum, Gift of the Artist, 15.316 BIOGRAPHY Lydia Field Emmet led a remarkably successful artistic career spanning more than 50 years. She is best known as a painter of portraits, particularly of children. Emmet was born in New Rochelle, New York, into a family of female artists. Her mother, Julia Colt Pierson Emmet, her sisters Rosina Emmet Sherwood and Jane Emmet de Glehn, and her cousin Ellen Emmet Rand were all painters. Lydia Emmet’s talent (and enterprise) was apparent early, as she began selling illustrations at the age of 14. In 1884 she accompanied Rosina to Europe, and they studied at the Académie Julian in Paris for six months. During the late 1880s Emmet sold wallpaper designs, made illustrations for Harper’s Weekly, and created stained glass designs for Tiffany Glass Company. From 1889 to 1895 Emmet studied at the Art Students League, where her instructors included William Merritt Chase (American, 1849 - 1916) and Kenyon Cox (American, 1856 - 1919). Chase appointed her an instructor at his Shinnecock Summer School of Art on Long Island, where she taught preparatory classes for several terms. Emmet also posed for one of his most elegant portraits, now in the collection of the Brooklyn Museum. Emmet, Lydia Field 1 © National Gallery of Art, Washington National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS American Paintings, 1900–1945 In 1893 both Emmet and her sister Rosina painted murals for the Women’s Building at the World’s Fair in Chicago. -

Jane Peterson Bio.Pages

Jane Peterson Biography Jennie Christine Peterson - Class of 1901 (1876 - 8/14/1965) - born in Elgin, Illinois, officially changed her name to Jane in 1909 following her first major American exhibition at the St. Botolph Club in Boston. As a child, she attended public school, but with her family’s support and encouragement, Peterson eventually applied and was accepted at the prestigious Pratt Institute in New York. While there, she studied under Arthur Wesley Dow. Peterson’s mother, proud of her daughter’s talent, and keen for her to succeed as an artist, provided her with $300 toward enrollment at the institute—a significant investment at the time for the family. After graduation in 1901, Peterson went on to study oil and watercolor painting at the Art Students League in New York City with Frank DuMond. By 1912, Peterson was teaching watercolor at the Art Students League and eventually became the Drawing Supervisor of the Brooklyn Public Schools. Like many young people, especially artists, Peterson extended her artistic education by taking the traditional grand tour of Europe. For the rest of her life she would frequently return to travel on the continent. The grand European tour was one of the best ways for young artists to view specific works of art and to learn from the masters. Peterson studied with Frank Brangwyn in Venice and London, Joaquin Sorolla in Madrid, and Jacques Blanche and Andre L’Hote in Paris. Under their direction she gained a diverse and expert knowledge of painting techniques and composition. Studying in Paris, Peterson also became friends with Gertrude and Leo Stein, becoming a regular at the sibling’s various gatherings where the guests included Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse. -

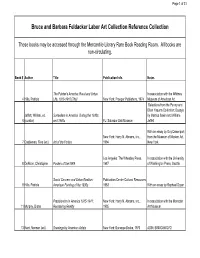

Bruce and Barbara Feldacker Labor Art Collection Reference Collection

Page 1 of 31 Bruce and Barbara Feldacker Labor Art Collection Reference Collection These books may be accessed through the Mercantile Library Rare Book Reading Room. All books are non-circulating. Book # Author Title Publication Info. Notes The Painter's America: Rural and Urban In association with the Whitney 4 Hills, Patricia Life, 1810-1910 [The] New York: Praeger Publishers, 1974 Museum of American Art Selections from the Penny and Elton Yasuna Collection; Essays Jeffett, William, ed. Surrealism in America During the 1930s by Martica Sawin and William 6 (curator) and 1940s FL: Salvador Dali Museum Jeffett With an essay by Guy Davenport; New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., from the Museum of Modern Art, 7 Castleman, Riva (ed.) Art of the Forties 1994 New York Los Angeles: The Wheatley Press, In association with the University 8 DeNoon, Christopher Posters of the WPA 1987 of Washington Press, Seattle Social Concern and Urban Realism: Publication Center Cultural Resources, 9 Hills, Patricia American Painting of the 1930s 1983 With an essay by Raphael Soyer Precisionism in America 1915-1941: New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., In association with the Montclair 11 Murphy, Diana Reordering Reality 1995 Art Museum 13 Kent, Norman (ed.) Drawings by American Artists New York: Bonanza Books, 1970 ASIN: B000G5WO7Q Page 2 of 31 Slatkin, Charles E. and New York: Oxford University Press, 14 Shoolman, Regina Treasury of American Drawings 1947 ASIN: B0006AR778 15 American Art Today National Art Society, 1939 ASIN: B000KNGRSG Eyes on America: The United States as New York: The Studio Publications, Introduction and commentary on 16 Hall, W.S. -

Miles Mcenery Gallery 525 West 22Nd Street, New York, NY 10011 | 511

BO BARTLETT (b. 1955, Columbus, GA) received his Certificate of Fine Arts in 1981 from the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and received a certificate in filmmaking from New York University in 1986. In January 2018, Columbus State University unveiled the Bo Bartlett Center, which features a permanent collection of Bartlett’s work. He has had numerous solo exhibitions internationally. Recent solo exhibitions include Miles McEnery Gallery, New York, NY; “Forty Years of Drawing”, The Florence Academy of Art, Jersey City, NJ; “Paintings and Works on Paper”, Weber Fine Art, Greenwich, CT; Miles McEnery Gallery, New York, NY; “Retrospective”, The Bo Bartlett Center, Columbus, GA; “Paintings from the Outpost”, Dowling Walsh Gallery, Rockland, ME; “Bo Bartlett: American Artist,” The Mennello Museum of American Art and the Orlando Museum of Art, Orlando, FL; Ameringer | McEnery | Yohe, New York, NY; Morris Museum of Art, Augusta, GA; University of Mississippi Museum, Oxford, MS; “Love and Other Sacraments,” Dowling Walsh Gallery, Rockland, ME; “Paintings of Home,” Ilges Gallery, Columbus State University, Columbus, GA; “A Survey of Paintings,” W.C. Bradley Co. Museum, Columbus, GA; “Sketchbooks, Journals and Studies,” Columbus Bank & Trust, Columbus, GA; Dowling Walsh Gallery, Rockland, ME and“Paintings of Home,” P.P.O.W. Gallery, New York, NY. Recent group exhibitions include “A Telling Instinct: John James Audubon and Contemporary Art,” Asheville Art Museum, Asheville, NC; “Bo Bartlett and Betsy Eby,” Ithan Substation No. 1, Villanova, PA; “Truth & Vision: 21st Century Realism,” Delaware Art Museum, Wilmington, DE; “Rockwell and Realism in an Abstract World,” Norman Rockwell Museum, Stockbridge, MA; “The Things We Carry: Contemporary Art in the South,” Gibbes Museum of Art, Charleston, SC; Nocturnes: Romancing the Night,” National Arts Club, New York, NY; “The Philadelphia Story,” Asheville Art Museum, Asheville, NC and “Best of the Northwest: Selected Paintings from the Permanent Collection,” Tacoma Art Museum, Tacoma, WA. -

Robert Henri American / Estadounidense, 1865–1929 Beatrice Whittaker Oil on Canvas, 1919

Daniel Garber American / Estadounidense, 1880–1958 Junior Camp Oil on board, ca. 1924 Daniel Garber served on the faculty of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts for over forty years. He started as a student in 1899, studying with William Merritt Chase. After being awarded a scholarship that allowed him to study in Europe for two years, he returned to Philadelphia in 1907, where he was first hired by Emily Sartain to teach at the Philadelphia School of Design for Women. This painting demonstrates a shift in Garber’s style, as he is known for his Impressionist landscapes. In the 1920s, Garber began experimenting with a heavier stitch-like brushstroke, as seen here, in one of his many depictions of the Delaware River embankment near his home and studio. Campamento juvenil Óleo sobre tabla, ca. 1924 Daniel Garber formó parte del cuerpo docente de la Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts durante más de cuarenta años. Comenzó como estudiante en 1899 y fue alumno de William Merritt Chase. Tras estudiar en Europa durante dos años gracias a una beca, regresó en 1907 a Filadelfia, donde fue contratado por primera vez por Emily Sartain para impartir clases en la Philadelphia School of Design for Women. Esta pintura pone de manifiesto un cambio estilístico en Garber, conocido por sus paisajes impresionistas. En la década de 1920, Garber comenzó a experimentar con pinceladas más empastadas, semejantes a puntadas, como se aprecia aquí en una de sus muchas representaciones del dique del río Delaware, cercano a su hogar y estudio. Gift of Bella Mabury in honor of Paul R. -

Hood M U S Eum O F A

H O O D M U S E U M O F A R T D A R T M O U T H C O L L E G E quarter y Spring/Summer 2011 Cecilia Beaux, Maud DuPuy Darwin (detail), 1889, pastel on warm gray paper laid down on canvas. Promised gift to the Hood Museum of Art from Russell and Jack Huber, Class of 1963. Jerry Rutter teaching with the Yale objects. H O O D M U SE U M O F A RT S TA F F Susan Achenbach, Art Handler Gary Alafat, Security/Buildings Manager Juliette Bianco, Acting Associate Director Amy Driscoll, Docent and Teacher Programs Coordinator Patrick Dunfey, Exhibitions Designer/Preparations Supervisor Rebecca Fawcett, Registrarial Assistant Nicole Gilbert, Exhibitions Coordinator Cynthia Gilliland, Assistant Registrar Katherine Hart, Interim Director and Barbara C. and Harvey P. Hood 1918 Curator of Academic Programming Deborah Haynes, Data Manager Alfredo Jurado, Security Guard L E T T E R F R O M T H E D I R E C T O R Amelia Kahl Avdic, Executive Assistant he Hood Museum of Art has seen a remarkable roster of former directors during Adrienne Kermond, Tour Coordinator the past twenty-five years who are still active and prominent members of the Vivian Ladd, Museum Educator T museum and art world: Jacquelynn Baas, independent scholar and curator and Barbara MacAdam, Jonathan L. Cohen Curator of emeritus director of the University of California Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific American Art Film Archive; James Cuno, director of the Art Institute of Chicago; Timothy Rub, Christine MacDonald, Business Assistant director of the Philadelphia Museum of Art; Derrick Cartwright, director of the Seattle Nancy McLain, Business Manager Art Museum; and Brian Kennedy, president and CEO of the Toledo Museum of Art. -

Fine Paintings

FINE PAINTINGS Tuesday,Tuesday, OctoberOctober 15, 2019 NEW YORK FINE PAINTINGS AUCTION Tuesday, October 15, 2019 at 10am EXHIBITION Friday, October 11, 10am – 5pm Saturday, October 12, 10am – 5pm Sunday, October 13, Noon – 5pm LOCATION DOYLE 175 East 87th Street New York City 212-427-2730 www.Doyle.com Catalog: $10 The Marian Sulzberger Heiskell & Andrew Heiskell Collection Doyle is honored to present The Marian Sulzberger INCLUDING PROPERTY FROM THE ESTATES OF Heiskell and Andrew Heiskell Collection in select Claire Chasanoff auctions throughout the Fall season. A civic leader David Follett and philanthropist, Marian championed outdoor James and Mary Freeborn community spaces across New York and led a The Marian Sulzberger Heiskell and nonprofit organization responsible for restoring Andrew Heiskell Collection the 42nd Street theatres. She was instrumental in Leonore Hodorowski the 1972 campaign to create the Gateway National A New York Estate Recreation Area, a 26,000-acre park with scattered beaches and wildlife refuges around the entrance to A Palm Beach Heiress the New York-New Jersey harbor. A Park Avenue Estate For 34 years, she worked as a Director of INCLUDING PROPERTY FROM The New York Times, where her grandfather, A Connecticut Private Collection father, husband, brother, nephew and grand-nephew Gertrude D. Davis Trust served as successive publishers. Her work at the The Metropolitan Museum of Art newspaper focused on educational projects. Two New York Gentlemen In 1965, Marian married Andrew Heiskell, A Palm Beach Collector the Chairman of Time Inc., whose philanthropies A Prominent Philadelphia Collector included the New York Public Library. A South Carolina Collector Property from The Marian Sulzberger Heiskell and Andrew Heiskell Collection in the October 15 auction comprises a pair of gouaches by French artist Ernest Pierre Guérin (lot 20).