Julia Thecla: Undiscovered Worlds Joanna Gardner-Hugget

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monster Roster: Existentialist Art in Postwar Chicago Receives First Major Exhibition, at University of Chicago’S Smart Museum of Art, February 11 – June 12, 2016

Contact C.J. Lind | 773.702.0176 | [email protected] For Immediate Release “One of the most important Midwestern contributions to the development of American art” MONSTER ROSTER: EXISTENTIALIST ART IN POSTWAR CHICAGO RECEIVES FIRST MAJOR EXHIBITION, AT UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO’S SMART MUSEUM OF ART, FEBRUARY 11 – JUNE 12, 2016 Related programming highlights include film screenings, monthly Family Day activities, and a Monster Mash Up expert panel discussion (January 11, 2016) The Smart Museum of Art at the University of Chicago, 5550 S. Greenwood Avenue, will mount Monster Roster: Existentialist Art in Postwar Chicago, the first-ever major exhibition to examine the history and impact of the Monster Roster, a group of postwar artists that established the first unique Chicago style, February 11–June 12, 2016. The exhibition is curated by John Corbett and Jim Dempsey, independent curators and gallery owners; Jessica Moss, Smart Museum Curator of Contemporary Art; and Richard A. Born, Smart Museum Senior Curator. Monster Roster officially opens with a free public reception, Wednesday, February 10, 7–9pm featuring an in-gallery performance by the Josh Berman Trio. The Monster Roster was a fiercely independent group of mid-century artists, spearheaded by Leon Golub (1922–2004), which created deeply psychological works drawing on classical mythology, ancient art, and a shared persistence in depicting the figure during a period in which abstraction held sway in international art circles. “The Monster Roster represents the first group of artists in Chicago to assert its own style and approach—one not derived from anywhwere else—and is one of the most important Midwestern contributions to the development of American art,” said co-curator John Corbett. -

The Factory of Visual

ì I PICTURE THE MOST COMPREHENSIVE LINE OF PRODUCTS AND SERVICES "bey FOR THE JEWELRY CRAFTS Carrying IN THE UNITED STATES A Torch For You AND YOU HAVE A GOOD PICTURE OF It's the "Little Torch", featuring the new controllable, méf » SINCE 1923 needle point flame. The Little Torch is a preci- sion engineered, highly versatile instrument capa- devest inc. * ble of doing seemingly impossible tasks with ease. This accurate performer welds an unlimited range of materials (from less than .001" copper to 16 gauge steel, to plastics and ceramics and glass) with incomparable precision. It solders (hard or soft) with amazing versatility, maneuvering easily in the tightest places. The Little Torch brazes even the tiniest components with unsurpassed accuracy, making it ideal for pre- cision bonding of high temp, alloys. It heats any mate- rial to extraordinary temperatures (up to 6300° F.*) and offers an unlimited array of flame settings and sizes. And the Little Torch is safe to use. It's the big answer to any small job. As specialists in the soldering field, Abbey Materials also carries a full line of the most popular hard and soft solders and fluxes. Available to the consumer at manufacturers' low prices. Like we said, Abbey's carrying a torch for you. Little Torch in HANDY KIT - —STARTER SET—$59.95 7 « '.JBv STARTER SET WITH Swest, Inc. (Formerly Southwest Smelting & Refining REGULATORS—$149.95 " | jfc, Co., Inc.) is a major supplier to the jewelry and jewelry PRECISION REGULATORS: crafts fields of tools, supplies and equipment for casting, OXYGEN — $49.50 ^J¡¡r »Br GAS — $49.50 electroplating, soldering, grinding, polishing, cleaning, Complete melting and engraving. -

BROWNIE the Complete Emarcy Recordings of Clifford Brown Including Newly Discovered Essential Material from the Legendary Clifford Brown – Max Roach Quintet

BROWNIE The Complete Emarcy Recordings of Clifford Brown Including Newly Discovered Essential Material from the Legendary Clifford Brown – Max Roach Quintet Dan Morgenstern Grammy Award for Best Album Notes 1990 Disc 1 1. DELILAH 8:04 Clifford Brown-Max RoaCh Quintet: (V. Young) Clifford Brown (tp), Harold Land (ts), Richie 2. DARN THAT DREAM 4:02 Powell (p), George Morrow (b), Max RoaCh (De Lange - V. Heusen) (ds) 3. PARISIAN THOROUGHFARE 7:16 (B. Powell) 4. JORDU 7:43 (D. Jordan) 5. SWEET CLIFFORD 6:40 (C. Brown) 6. SWEET CLIFFORD (CLIFFORD’S FANTASY)* 1:45 1~3: Los Angeles, August 2, 1954 (C. Brown) 7. I DON’T STAND A GHOST OF A CHANCE* 3:03 4~8: Los Angeles, August 3, 1954 (Crosby - Washington - Young) 8. I DON’ T STAND A GHOST OF A CHANC E 7:19 9~12: Los Angeles, August 5, 1954 (Crosby - Washington - Young) 9. STOMPIN’ AT TH E SAVOY 6:24 (Goodman - Sampson - Razaf - Webb) 10. I GET A KICK OUT OF YOU 7:36 (C. Porter) 11. I GET A KICK OUT OF YOU* 8:29 * Previously released alternate take (C. Porter) 12. I’ LL STRING ALONG WITH YOU 4:10 (Warren - Dubin) Disc 2 1. JOY SPRING* 6:44 (C. Brown) Clifford Brown-Max RoaCh Quintet: 2. JOY SPRING 6:49 (C. Brown) Clifford Brown (tp), Harold Land (ts), Richie 3. MILDAMA* 3:33 (M. Roach) Powell (p), George Morrow (b), Max RoaCh (ds) 4. MILDAMA* 3:22 (M. Roach) Los Angeles, August 6, 1954 5. MILDAMA* 3:55 (M. Roach) 6. -

Selected Highlights of Women's History

Selected Highlights of Women’s History United States & Connecticut 1773 to 2015 The Permanent Commission on the Status of Women omen have made many contributions, large and Wsmall, to the history of our state and our nation. Although their accomplishments are too often left un- recorded, women deserve to take their rightful place in the annals of achievement in politics, science and inven- Our tion, medicine, the armed forces, the arts, athletics, and h philanthropy. 40t While this is by no means a complete history, this book attempts to remedy the obscurity to which too many Year women have been relegated. It presents highlights of Connecticut women’s achievements since 1773, and in- cludes entries from notable moments in women’s history nationally. With this edition, as the PCSW celebrates the 40th anniversary of its founding in 1973, we invite you to explore the many ways women have shaped, and continue to shape, our state. Edited and designed by Christine Palm, Communications Director This project was originally created under the direction of Barbara Potopowitz with assistance from Christa Allard. It was updated on the following dates by PCSW’s interns: January, 2003 by Melissa Griswold, Salem College February, 2004 by Nicole Graf, University of Connecticut February, 2005 by Sarah Hoyle, Trinity College November, 2005 by Elizabeth Silverio, St. Joseph’s College July, 2006 by Allison Bloom, Vassar College August, 2007 by Michelle Hodge, Smith College January, 2013 by Andrea Sanders, University of Connecticut Information contained in this book was culled from many sources, including (but not limited to): The Connecticut Women’s Hall of Fame, the U.S. -

Louise Bourgeois Brochure

LOUISE BOURGEOIS American, French born (1911 - 2010) The Blind Leading The Blind 1947 - 49, painted wood 70⅜ × 96⅞ × 17⅜ in. Regents Collections Acquisition Program with Match- ing Funds from the Jerome L. Greene, Agnes Gund, Sydney and Frances Lewis, and Leonard C. Yaseen Purchase Fund, 1989 Living in New York during the mid 1940s, when World War II cut her off from friends and family in France, Louise Bourgeois created vertical wood sculptures that she exhibited as loosely grouped, solitary figures. These objects represented sorely missed people and her own loneliness and isolation in America. In 1948, Bourgeois made the first of five variations of The Blind Leading The Blind as pairs of legs which, unable to stand alone, were bound together for strength by lintel like boards. The figures appear to walk tentatively on tiptoe under the boards, the weight of which presses down on the individual pairs even as it holds them togeth- er as an uneasy collective. One of the artist’s most abstract works, this sculpture takes on an anthropomorphic presence by resting directly on the floor and sharing the viewer’s space. In 1949, after being called before the House Un-American Activities Commit- tee, Bourgeois named the series The Blind Leading the Blind. The title paraphras- es Jesus’s description of the hypocritical Pharisees and scribes (Matthew 15:14): “Let them alone, they are blind guides. And if a blind man leads a blind man, both will fall into a pit.” Exposing the folly of untested belief, unscrutinized ritual, and regimented thinking, the parable has been used as a subject by other artists. -

Chicago Tourist Information 7 August, 2003

Lepton Photon 2003 Chicago Tourist Information 7 August, 2003 XXI International Symposium on Lepton and Photon Interactions at High Energies Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, Batavia, IL USA 11 – 16 August 2003 CHICAGO TOURIST INFORMATION Wednesday 13 August 2003 is a free day at the Lepton Photon 2003 Symposium. The Symposium banquet will be held in the evening at Navy Pier in downtown Chicago. It will begin with a reception at 6:30 p.m., followed by dinner at 7:30 p.m. There will be a lakefront fireworks display right off the pier at 9:30 p.m. Buses will depart from Navy Pier around 10:00 p.m. We hope that many of you will take advantage of the time to visit Chicago. We will run several buses to Chicago in the morning. There will be a few additional buses in the afternoon. Detailed schedules will be available at the beginning of the conference and sign-up for the bus transportation is requested. We have some suggestions for tours you might take or sights you might see depending on your interests. Please be aware that many of the attractions are internationally renowned and, depending on the time of the year and the weather, can be quite crowded and have long waits for admission. In some cases, you can get tickets in advance through the web or Ticketron. All times and fees are for Wednesday, 13 August 2003 and do vary from day to day. More information is available in the materials we have provided in the registration packet and at the official city of Chicago Website: http://www.cityofchicago.org. -

Maria Tall Chief Maria Tall Chief

Maria Tall Chief Maria Tall Chief (later changed to Tallchief) was born in Oklahoma in 1925. Her father was Osage Native American and her mother of Scotch-Irish descent. It had been an unrealized dream of her mom to study dance and music, so Maria and her sister Marjorie were enrolled early in dance and piano lessons. Maria was only three years old when she began dance classes. It wasn’t long before Maria and Marjorie were performing at local rodeos. When she was eight, Maria’s family moved to California with the hope finding an opportunity for the girls in show business. Her mother asked a pharmacist for a recommendation for a dance teacher and was referred to Ernest Belcher, who was Marge Champion’s father. Maria soon moved on to more noted classical teachers of dance, but was also continuing to study piano and saw herself as having a career as a classical pianist. However, she continued with dance and at 17 went to New York looking for a way into the classical world of dance. Tallchief was soon offered a place with the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo where she performed for five years. It was there that she met George Balanchine. She eventually married Balanchine and returned to New York. Balanchine had just founded the New York City Ballet and Maria became its first prima ballerina. She was the first American woman and the first Native American to be recognized world wide as a prima ballerina. She was the first American invited to dance with the Bolshoi. -

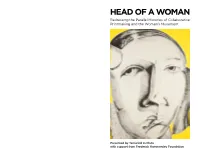

Head of a Woman Program Final Digital

HEAD OF A WOMAN Redressing the Parallel Histories of Collaborative Printmaking and the Women’s Movement Presented by Tamarind Institute with support from Frederick Hammersley Foundation Sixty years ago June Wayne, founder of collaborative printmaking over the past sixty years. The rise of Tamarind Lithography Workshop, submitted contemporary printmaking in the 1960s and 1970s runs parallel to the her proposal to the Ford Foundation to burgeoning women’s movement, which no doubt contributed to the establish a model workshop in Los Angeles, steady surge of women printers and printmakers. Head of a Woman brings together an intergenerational roster of artists, printers, scholars, specifically designed to restore the fine and publishers, with the hopes of reflecting on this intertwined history art of lithography. This symposium pays and propelling the industry--and the thinking around prints--forward. tribute to the creative industry that Wayne imagined, and the many remark- Diana Gaston able women who shaped the field of Director, Tamarind Institute 11:00 | THE LONG VIEW: WOMEN IN THE TAMARIND MORNING WORKSHOP AND THEIR CONTINUED IMPACT PRESENTATIONS CHRISTINE ADAMS holds a BFA in printmaking from Arizona State University and received 9:30 | DOORS OPEN her Tamarind Master Printer certificate in May 10:00 | INTRODUCTION 2019. Her printing experience includes positions at the LeRoy Neiman Center for Print Studies at Columbia University and Lower East Side 10:15 | INKED UP: SIXTY YEARS Printshop. Adams is currently a collaborative printer at Universal Limited Art Editions (ULAE) OF COLLABORATIVE WOMEN PRINTMAKERS and a member of the printmaking faculty at Parsons School of Design in New York City. -

Oral History Interview with Rachel Rosenthal

Oral history interview with Rachel Rosenthal Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 General............................................................................................................................. 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 1 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 1 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 2 Container Listing ...................................................................................................... Oral history interview with Rachel Rosenthal AAA.rosent89 Collection Overview Repository: Archives of American Art Title: Oral history interview with Rachel Rosenthal Identifier: AAA.rosent89 Date: 1989 September 2-3 Creator: Rosenthal, Rachel, 1926- (Interviewee) Roth, Moira (Interviewer) Women in the -

WORK EXPERIENCE ART INSTITUTE of CHICAGO Collection Manager for the Department of European Painting & Sculpture (EPS). Respo

DEVON L. PYLE-VOWLES 847-903-7940 email: [email protected] WORK EXPERIENCE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO Collection Manager for the Department of European Painting & Sculpture (EPS). Responsible for the department’s collection, including acquisitions, outgoing loans, incoming loans, deaccessions, object files, database records, metadata, and research materials. Coordinated and managed activities pertaining to the permanent collection, including the administration of new acquisitions, conservation treatment requests, gallery rotations and installations, loans, storage, documentation of permanent collection objects and promised gifts, and external research inquiries. When necessary, couriered the EPS collection for outgoing loan program of the AIC (about 10 times a year). Under advisement of curators, published accurate object information online through the museum’s databases, ensuring data fidelity and actively managed the tagging of the EPS collection. Served as liaison between department chair and curators, technicians, specialists, and support staff. As the main point of contact, collaborated with the departments of Collections and Loans, Experience Design on developing and maintaining accurate collection data on the website; Conservation and Science, Facilities, Imaging, the Office of the Secretary to the Board of Trustees. Also, coordinated communications when necessary with lenders, donors, estates, appraisers, EPS committee members, galleries, and collectors.(June 2014-July 2020) Collections Inventory Manager for the Department of European Decorative Arts. Responsible for developing, coordinating and implementing the protocol for the inventory project which included the collection being photographed for the database and the website. Maintained and updated the departmental accession files, location lists and corresponding Art Institute (AIC) database records for the European Decorative Arts collection. Worked closely with the Curator and Preparatory specialist on the collection assessment and photography process. -

Thomas Newbolt: Drama Painting – a Modern Baroque

NAE MAGAZINE i NAE MAGAZINE ii CONTENTS CONTENTS 3 EDITORIAL Off Grid - Daniel Nanavati talks about artists who are working outside the established art market and doing well. 6 DEREK GUTHRIE'S FACEBOOK DISCUSSIONS A selection of the challenging discussions on www.facebook.com/derekguthrie 7 THE WIDENING CHASM BETWEEN ARTISTS AND CONTEMPORARY ART David Houston, curator and academic, looks at why so may contemporary artists dislike contemporary art. 9 THE OSCARS MFA John Steppling, who wrote the script for 52nd Highway and worked in Hollywood for eight years, takes a look at the manipulation of the moving image makers. 16 PARTNERSHIP AGREEMENT WITH PLYMOUTH COLLEGE OF ART Our special announcement this month is a partnering agreement between the NAE and Plymouth College of Art 18 SPEAKEASY Tricia Van Eck tells us that artists participating with audiences is what makes her gallery in Chicago important. 19 INTERNET CAFÉ Tom Nakashima, artist and writer, talks about how unlike café society, Internet cafés have become. Quote: Jane Addams Allen writing on the show: British Treasures, From the Manors Born 1984 One might almost say that this show is the apotheosis of the British country house " filtered through a prism of French rationality." 1 CONTENTS CONTENTS 21 MONSTER ROSTER INTERVIEW Tom Mullaney talks to Jessica Moss and John Corbett about the Monster Roster. 25 THOUGHTS ON 'CAST' GRANT OF £500,000 Two Associates talk about one of the largest grants given to a Cornwall based arts charity. 26 MILWAUKEE MUSEUM'S NEW DESIGN With the new refurbishment completed Tom Mullaney, the US Editor, wanders around the inaugural exhibition. -

Feminist Scholarship Review: Women in Theater and Dance

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Feminist Scholarship Review Women and Gender Resource Action Center Spring 1998 Feminist Scholarship Review: Women in Theater and Dance Katharine Power Trinity College Joshua Karter Trinity College Patricia Bunker Trinity College Susan Erickson Trinity College Marjorie Smith Trinity College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/femreview Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Power, Katharine; Karter, Joshua; Bunker, Patricia; Erickson, Susan; and Smith, Marjorie, "Feminist Scholarship Review: Women in Theater and Dance" (1998). Feminist Scholarship Review. 10. https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/femreview/10 Peminist Scfiofarsliip CR§view Women in rrlieater ana(])ance Hartford, CT, Spring 1998 Peminist ScfioCarsfiip CJ?.§view Creator: Deborah Rose O'Neal Visiting Lecturer in the Writing Center Trinity College, Hartford, Connecticut Editor: Kimberly Niadna Class of2000 Contributers: Katharine Power, Senior Lecturer ofTheater and Dance Joshua Kaner, Associate Professor of Theater and Dance Patricia Bunker, Reference Librarian Susan Erickson, Assistant to the Music and Media Services Librarian Marjorie Smith, Class of2000 Peminist Scfzo{a:rsnip 9.?eview is a project of the Trinity College Women's Center. For more information, call 1-860-297-2408 rr'a6fe of Contents Le.t ter Prom. the Editor . .. .. .... .. .... ....... pg. 1 Women Performing Women: The Body as Text ••.•....••..••••• 2 by Katharine Powe.r Only Trying to Move One Step Forward • •.•••.• • • ••• .• .• • ••• 5 by Marjorie Smith Approaches to the Gender Gap in Russian Theater .••••••••• 8 by Joshua Karter A Bibliography on Women in Theater and Dance ••••••••.••• 12 by Patricia Bunker Women in Dance: A Selected Videography .••• .•...