Chabad V. Russian Federation, 466 F.Supp.2D 6 (2006)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Tribu1e 10 Eslller, Mv Panner in Torah

gudath Israel of America's voice in kind of informed discussion and debate the halls of courts and the corri that leads to concrete action. dors of Congress - indeed every A But the convention is also a major where it exercises its shtadlonus on yardstick by which Agudath Israel's behalf of the Kial - is heard more loudly strength as a movement is measured. and clearly when there is widespread recognition of the vast numbers of peo So make this the year you ple who support the organization and attend an Agm:fah conventicm. share its ideals. Resente today An Agudah convention provides a forum Because your presence sends a for benefiting from the insights and powerfo! - and ultimately for choice aa:ommodotions hadracha of our leaders and fosters the empowering - message. call 111-m-nao is pleased to announce the release of the newest volume of the TlHllE RJENNlERT JED>JITJION ~7~r> lEN<ClY<ClUO>lPElOl l[}\ ~ ·.:~.~HDS. 1CA\J~YA<Gr M(][1CZ\V<Q . .:. : ;······~.·····················.-~:·:····.)·\.~~····· ~s of thousands we~ed.(>lig~!~d~ith the best-selling mi:i:m niw:.r c .THE :r~~··q<:>Jy(MANDMENTS, the inaugural volume of theEntzfl(lj)('dia (Mitzvoth 25-38). Now join us aswestartfromthebeginning. The En~yclop~dia provides yau with • , • A panciramicviewofthe entire Torah .Laws, cust9ms and details about each Mitzvah The pririlafy reasons and insights for each Mitzvah. tteas.. ury.· of Mid. ra. shim and stories from Cha. zal... and m.uc.h.. n\ ''"'''''' The Encyclopedia of the Taryag Mitzvoth The Taryag Legacy Foundation is a family treasure that is guaranteed to wishes to thank enrich, inspire, and elevate every Jewish home. -

A Fresh Perspective on the History of Hasidic Judaism

eSharp Issue 20: New Horizons A Fresh Perspective on the History of Hasidic Judaism Eva van Loenen (University of Southampton) Introduction In this article, I shall examine the history of Hasidic Judaism, a mystical,1 ultra-orthodox2 branch of Judaism, which values joyfully worshipping God’s presence in nature as highly as the strict observance of the laws of Torah3 and Talmud.4 In spite of being understudied, the history of Hasidic Judaism has divided historians until today. Indeed, Hasidic Jewish history is not one monolithic, clear-cut, straightforward chronicle. Rather, each scholar has created his own narrative and each one is as different as its author. While a brief introduction such as this cannot enter into all the myriad divergences and similarities between these stories, what I will attempt to do here is to incorporate and compare an array of different views in order to summarise the history of Hasidism and provide a more objective analysis, which has not yet been undertaken. Furthermore, my historical introduction in Hasidic Judaism will exemplify how mystical branches of mainstream religions might develop and shed light on an under-researched division of Judaism. The main focus of 1 Mystical movements strive for a personal experience of God or of his presence and values intuitive, spiritual insight or revelationary knowledge. The knowledge gained is generally ‘esoteric’ (‘within’ or hidden), leading to the term ‘esotericism’ as opposed to exoteric, based on the external reality which can be attested by anyone. 2 Ultra-orthodox Jews adhere most strictly to Jewish law as the holy word of God, delivered perfectly and completely to Moses on Mount Sinai. -

Preliminary Programme

Preliminary Programme DLM Forum Member Meeting 28-29th November 2018 Vienna, Austria The Austrian States Archives are pleased to invite members of the DLM Forum to the Mem- ber Meeting in Vienna on the 28th and 29th of November, 2018. The venue of the meeting is the Conference Hall of the Austrian State Archives (Notten- dorfer Gasse 2, 1030 Vienna). The Archives are situated only 5 stops by underground from the City Center. During the conference, Vienna will be in the middle of the holiday season. The city comes alive with lights, music, Christmas Markets and more. If you are considering a long weekend in Vienna, you might enjoy the magical Christmas spirit and get some gifts at its great shop- ping boulevards. The Christmas markets are selling traditional food, mulled wine and hand crafted goods and are loved by both locals and tourists alike. Please visit DLM Forum website and register If you have any questions, please contact Ms Beatrix Horvath at [email protected] See you in Vienna! Wednesday 28th November CROSS-BORDER COOPERATION AND NEW SOLUTIONS FOR DIGITAL DATA 11:45 – 12:20 Registration and coffee / tea 12:20 – 12:30 Welcome Chair: Jan Dalsten Sørensen Jan Dalsten Sørensen, Welcome from the chair of the DLM Forum and Chair of the DLM Forum the Austrian State Archives Mrs. Karin Holzer, Austrian State Archives Chair: Jonas Kerschner, Austrian 13:30 – 14:30 Session I, Interactive session States Archives J. Dalsten Sørensen, Danish National Archives, Denmark Meet the new eArchiving Building Block Mrs. Manuela Speiser, European -

Lelov: Cultural Memory and a Jewish Town in Poland. Investigating the Identity and History of an Ultra - Orthodox Society

Lelov: cultural memory and a Jewish town in Poland. Investigating the identity and history of an ultra - orthodox society. Item Type Thesis Authors Morawska, Lucja Rights <a rel="license" href="http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/3.0/"><img alt="Creative Commons License" style="border-width:0" src="http://i.creativecommons.org/l/by- nc-nd/3.0/88x31.png" /></a><br />The University of Bradford theses are licenced under a <a rel="license" href="http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/">Creative Commons Licence</a>. Download date 03/10/2021 19:09:39 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10454/7827 University of Bradford eThesis This thesis is hosted in Bradford Scholars – The University of Bradford Open Access repository. Visit the repository for full metadata or to contact the repository team © University of Bradford. This work is licenced for reuse under a Creative Commons Licence. Lelov: cultural memory and a Jewish town in Poland. Investigating the identity and history of an ultra - orthodox society. Lucja MORAWSKA Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Social and International Studies University of Bradford 2012 i Lucja Morawska Lelov: cultural memory and a Jewish town in Poland. Investigating the identity and history of an ultra - orthodox society. Key words: Chasidism, Jewish History in Eastern Europe, Biederman family, Chasidic pilgrimage, Poland, Lelov Abstract. Lelov, an otherwise quiet village about fifty miles south of Cracow (Poland), is where Rebbe Dovid (David) Biederman founder of the Lelov ultra-orthodox (Chasidic) Jewish group, - is buried. -

Genocide, Memory and History

AFTERMATH GENOCIDE, MEMORY AND HISTORY EDITED BY KAREN AUERBACH AFTERMATH AFTERMATH GENOCIDE, MEMORY AND HISTORY EDITED BY KAREN AUERBACH Aftermath: Genocide, Memory and History © Copyright 2015 Copyright of the individual chapters is held by the chapter’s author/s. Copyright of this edited collection is held by Karen Auerbach. All rights reserved. Apart from any uses permitted by Australia’s Copyright Act 1968, no part of this book may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the copyright owners. Inquiries should be directed to the publisher. Monash University Publishing Matheson Library and Information Services Building 40 Exhibition Walk Monash University Clayton, Victoria, 3800, Australia www.publishing.monash.edu Monash University Publishing brings to the world publications which advance the best traditions of humane and enlightened thought. Monash University Publishing titles pass through a rigorous process of independent peer review. www.publishing.monash.edu/books/agmh-9781922235633.html Design: Les Thomas ISBN: 978-1-922235-63-3 (paperback) ISBN: 978-1-922235-64-0 (PDF) ISBN: 978-1-876924-84-3 (epub) National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: Title: Aftermath : genocide, memory and history / editor Karen Auerbach ISBN 9781922235633 (paperback) Series: History Subjects: Genocide. Genocide--Political aspects. Collective memory--Political aspects. Memorialization--Political aspects. Other Creators/Contributors: Auerbach, Karen, editor. Dewey Number: 304.663 CONTENTS Introduction ............................................... -

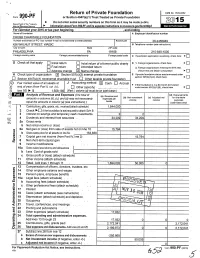

990-PF Return of Private Foundation

Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990-PF or Section 4947(a)(1) Trust Treated as Private Foundation Do not enter social security numbers on this form as it may be made public. M015 Department of the Treasury ► Internal R venue Service ► Information about Form 990-PF and its separate instructions is at www.irs.gov/form990 For calendar year 2015 or tax year beg innin g and endin g Name of foundation A Employer identification number CHUBB C HARITABLE FOUNDATION Number and street (or P O box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite 26-2456949 436 WALNUT STREET, WA09C B Telephone number (see instructions) City or town State ZIP code PHILADELPHIA PA 19106 215-640-1000 Foreign country name Foreign province/state/county Foreign postal code I q C If exemption application is pending, check here ► q q G Check all that apply, Initial return q Initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations, check here ► q Final return q Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, q q Address change Q Name change check here and attach computation ► H Check type of organization Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated under q section 507(b)(1)(A), check here ► q Section 4947 (a)( 1 ) nonexem pt charitable trust Other taxable p rivate foundation Fair market value of all assets at J Accounting method © Cash q Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination q end of year (from Part fl, co/ (c), q Other (specify) under section 507(b)( 1)(B), check here ------------------------- ► '9 line 10; t . -

Justice on Trial German Unification and the 1992 Leipzig Trial

Justice on Trial German Unification and the 1992 Leipzig Trial Emily Purvis Candidate for Senior Honors in History, Oberlin College Thesis Advisor: Professor Annemarie Sammartino/ Professor Renee Romano Spring 2020 Table of Contents Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………………. 1 Chapter 1: A New Germany ………………………………………………………………...... 13 Political Unification Legal Unification and Constitutional Amendment Rehabilitation and Compensation for Victims of the GDR First and Second Statute(s) for the Correction of SED Injustice Trials of the NVA Border Guards Chapter 2: Trying the DDR…………………………………………………………………… 33 The Indictment The Proceedings The Verdict Chapter 3: A Divided Public…………………………………………………………………... 53 Leniency Critique Victor’s Justice Critique Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………... 70 Bibliography…………………………………………………………………………………… 73 Purvis 1 Introduction In late September 1992, the District Court of Leipzig in eastern Germany handed down an indictment of former East German judge Otto Fuchs. Shortly thereafter, Judge Fuchs and his wife jumped out of a seventh story window. Fuchs was found in the morning, clutching his wife’s hand as they lay, lifeless, on the cobblestone street below.1 This tragic act marked the end of Fuchs’ story, and the beginning of another, for Fuchs was not the only one subpoenaed by the Leipzig District Court that day. The court charged eighty-six-year-old Otto Jürgens with the same crime, and unlike his colleague, who jumped to his death to avoid being brought to justice, Jürgens decided to face his fate head-on. These two men, only one of which lived to see his day in court, were being charged for their roles in orchestrating one of the most notorious show trials in East German history: the Waldheim Trials. -

THE GERMAN ARCHIVAL SYSTEM 1945-1995 By

THE GERMAN ARCHIVAL SYSTEM 1945-1995 by REGINA LANDWEHR B.Sc.(Hons.), The University of Calgary, 1993 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARCHIVAL STUDIES in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES SCHOOL OF LIBRARY, ARCHIVAL AND INFORMATION STUDIES We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April 1996 © Regina Landwehr 1996 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. -Department The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Date APnJL 2.2/ 14% DE-6 (2/88) ABSTRACT After World War Two, Germany became divided into two countries commonly called East and West Germany. This thesis describes how the two countries, one communist and one pluralistic, developed distinctly different archival systems with respect to the organization, legislation and appraisal methods of government archival institutions. East Germany's archival system was organized and legislated into a rigorous hierarchical structure under central government control with the mandate of fulfilling in a systematic way primarily ideological objectives. Although professional collaboration between the archivists of the two countries had been officially severed since the early years of separation by East Germany, because of irreconcilable political differences, they influenced each others' thoughts. -

After Chabad: Enforcement in Cultural Property Disputes

Comment After Chabad: Enforcement in Cultural Property Disputes Giselle Barciat I. INTRODUCTION Cultural property is a unique form of property. It may be at once personal property and real property; it is non-fungible; it carries deep historical value; it educates; it is part tangible, part transient.' Cultural property is property that has acquired a special social status inextricably linked to a certain group's identity. Its value to the group is unconnected to how outsiders might assess its economic worth. 2 If, as Hegel posited, property is an extension of personhood, then cultural property, for some, is an extension of nationhood. Perhaps because of that unique status, specialized rules have developed, both domestically and internationally, to resolve some of the legal ambiguities inherent in "owning" cultural property. The United States, for example, has passed numerous laws protecting cultural property4 and has joined treaties and participated in international conventions affirming cultural property's special legal status.5 Those rules focus primarily on conflict prevention and rely upon t Yale Law School, J.D. expected 2013; University of Cambridge, M.Phil. 2009; Harvard University, A.B. 2008. Many thanks to Professor Amy Chua for her supervision, support, and insightful comments. I am also grateful to Camey VanSant and Leah Zamore for their meticulous editing. And, as always, thanks to Daniel Schuker. 1. The United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property (1970 UNESCO Convention) defines cultural property as "property which, on religious or secular grounds, is specifically designated by each State as being of importance for archaeology, prehistory, history, literature, art or science." 1970 UNESCO Convention art. -

From Paris to Abroad - Diversity in Europe- in Varietate Concordia (EC, Brussels, 2000)

From Paris to abroad - Diversity in Europe- In varietate Concordia (EC, Brussels, 2000) - - issue 6 a newsletter edited by the Institute for Research and Information on Volunteering (iriv)- www.iriv.net available on www.club-iriv.net « Thesestrangers in a foreign World « Ces Etrangères, en Monde inconnu Protection asked of me- Asilem’ontdemandé Befriendthem, lest yourself in Heaven Accueille-les, car Toi- même au Ciel Be found a refugee” Pourrait être une Réfugiée » Emily Dickinson (Quatrains II-2, 1864-65, Amherst, Massachusetts, Etats-Unis) traduction en français de Claire Malroux (NRF, Poésie/Gallimard, Paris, 2000) directrice de la publication : dr Bénédicte Halba, présidente de l’iriv, co-fondatrice du club de l’iriv à la Cité des Métiers © iriv, Paris, 03/ 2019 1 From Paris to Thessaloniki The main characteristic of France is to be a secular country in which “the state The Institute for Research and Information on Volunteering (Iriv) has published since becomes modern, in this view, by suppressing or privatizing religion because it is taken to represent their rationality of tradition, an obstacle to open debate September 2016 a newsletter dedicated to migration- Regards Croisés sur la Migration. Its main aim is to tackle the issue of diversity- the motto chosen for the European Union and discussion” and whose “effect can be intolerance and (EU) since 2000 and definitely in 2004 after the entrance of ten new EU country members discrimination”(Weil, 2009). Nonetheless former French Minister for Culture (it enlarged from 15 members to 25). André Malraux underlined that the 21st Century would be religious (or mystic) or wouldn’t be”. -

Download Catalogue

F i n e Ju d a i C a . pr i n t e d bo o K s , ma n u s C r i p t s , au t o g r a p h Le t t e r s , gr a p h i C & Ce r e m o n i a L ar t K e s t e n b a u m & Co m p a n y We d n e s d a y , ma r C h 21s t , 2012 K e s t e n b a u m & Co m p a n y . Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art A Lot 275 Catalogue of F i n e Ju d a i C a . PRINTED BOOKS , MANUSCRI P TS , AUTOGRA P H LETTERS , GRA P HIC & CERE M ONIA L ART Featuring: Property from the Library of a New England Scholar ——— To be Offered for Sale by Auction, Wednesday, 21st March, 2012 at 3:00 pm precisely ——— Viewing Beforehand: Sunday, 18th March - 12:00 pm - 6:00 pm Monday, 19th March - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm Tuesday, 20th March - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm No Viewing on the Day of Sale This Sale may be referred to as: “Maymyo” Sale Number Fifty Four Illustrated Catalogues: $38 (US) * $45 (Overseas) KestenbauM & CoMpAny Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art . 242 West 30th street, 12th Floor, new york, NY 10001 • tel: 212 366-1197 • Fax: 212 366-1368 e-mail: [email protected] • World Wide Web site: www.Kestenbaum.net K e s t e n b a u m & Co m p a n y . -

Confronting Muted Memories Reading Silences, Entangling Histories

BALTIC WORLDSBALTIC A scholarly journal and news magazine. December 2020. Vol. XIII:4. From the Centre for Baltic and East European Studies (CBEES), Södertörn University. Special Issue: 92 pages of memory studies December 2020. Vol. XIII:4 XIII:4 Vol. 2020. December Breaking BALTIC the silence through art Visualizing WORLDSbalticworlds.com traumatic events Sites and places for remembrance Bringing generations together Special issue: issue: Special Confronting Reading Silences, Entangling Histries Entangling Silences, Reading muted memories Reading Silences, Entangling Histories also in this issue Sunvisson Karin Illustration: ARCHIVES IN TALLINN / HOLOCAUST IN BELARUS / HOLODOMOR IN UKRAINE/ OBLIVION IN POLAND Sponsored by the Foundation BALTIC for Baltic and East European Studies WORLDSbalticworlds.com editorial in this issue Dealing with the demons of the past here are many aspects of the past even after generations. An in- that we talk little about, if at all. The dividual take is often the case, dark past casts shadows and when and the own family history is silenced for a long time, it will not drawn into this exploring artistic Tleave the bearer at peace. Nations, minorities, process. By facing the demons of families, and individuals suffer the trauma of the past through art, we may be the past over generations. The untold doesn’t able to create new conversations go away and can even tear us apart if not dealt and learn about our history with Visual with. Those are the topics explored in this Spe- less fear and prejudice, runs the representation cial Issue of Baltic Worlds “Reading Silences, argument. Film-makers, artists Entangling Histories”, guest edited by Margaret and researchers share their un- of the Holodomor Tali and Ieva Astahovska.