2020 Forest Action Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lepidoptera of North America 5

Lepidoptera of North America 5. Contributions to the Knowledge of Southern West Virginia Lepidoptera Contributions of the C.P. Gillette Museum of Arthropod Diversity Colorado State University Lepidoptera of North America 5. Contributions to the Knowledge of Southern West Virginia Lepidoptera by Valerio Albu, 1411 E. Sweetbriar Drive Fresno, CA 93720 and Eric Metzler, 1241 Kildale Square North Columbus, OH 43229 April 30, 2004 Contributions of the C.P. Gillette Museum of Arthropod Diversity Colorado State University Cover illustration: Blueberry Sphinx (Paonias astylus (Drury)], an eastern endemic. Photo by Valeriu Albu. ISBN 1084-8819 This publication and others in the series may be ordered from the C.P. Gillette Museum of Arthropod Diversity, Department of Bioagricultural Sciences and Pest Management Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO 80523 Abstract A list of 1531 species ofLepidoptera is presented, collected over 15 years (1988 to 2002), in eleven southern West Virginia counties. A variety of collecting methods was used, including netting, light attracting, light trapping and pheromone trapping. The specimens were identified by the currently available pictorial sources and determination keys. Many were also sent to specialists for confirmation or identification. The majority of the data was from Kanawha County, reflecting the area of more intensive sampling effort by the senior author. This imbalance of data between Kanawha County and other counties should even out with further sampling of the area. Key Words: Appalachian Mountains, -

Influences of Trees on Abundance of Natural Enemies of Insect Pests: a Review*

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Agronomy & Horticulture -- Faculty Publications Agronomy and Horticulture Department 1995 Influences of rT ees on Abundance of Natural Enemies of Insect Pests: A Review Mary Ellen Dix United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service R. J. Johnson University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Mark O. Harrell University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Ronald M. Case University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Robert J. Wright University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/agronomyfacpub Part of the Plant Sciences Commons Dix, Mary Ellen; Johnson, R. J.; Harrell, Mark O.; Case, Ronald M.; Wright, Robert J.; Hodges, Laurie; Brandle, James R.; Schoeneberger, Michelle M.; Sunderman, N. J.; Fitzmaurice, R. L.; Young, Linda J.; and Hubbard, Kenneth G., "Influences of rT ees on Abundance of Natural Enemies of Insect Pests: A Review" (1995). Agronomy & Horticulture -- Faculty Publications. 412. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/agronomyfacpub/412 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Agronomy and Horticulture Department at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Agronomy & Horticulture -- Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Authors Mary Ellen Dix, R. J. Johnson, Mark O. Harrell, Ronald M. Case, Robert J. Wright, Laurie Hodges, James R. Brandle, Michelle M. Schoeneberger, N. J. Sunderman, R. L. Fitzmaurice, Linda J. Young, and Kenneth G. Hubbard This article is available at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/ agronomyfacpub/412 Dix, Johnson, Harrell, Case, Wright, Hodges, Brandle, Schoenberger, Sunderman, Fitzmaurice, Young & Hubbard in Agroforestry Systems 29 (1995) Agroforestry Systems 29: 303-311, 1995. -

Roosevelt Wild Life Bulletins the Roosevelt Wild Life Station

SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry Digital Commons @ ESF Roosevelt Wild Life Bulletins The Roosevelt Wild Life Station 1926 Roosevelt Wild Life Bulletin Charles C. Adams SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.esf.edu/rwlsbulletin Part of the Animal Sciences Commons, Biodiversity Commons, Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, and the Natural Resources and Conservation Commons Recommended Citation Adams, Charles C., "Roosevelt Wild Life Bulletin" (1926). Roosevelt Wild Life Bulletins. 23. https://digitalcommons.esf.edu/rwlsbulletin/23 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the The Roosevelt Wild Life Station at Digital Commons @ ESF. It has been accepted for inclusion in Roosevelt Wild Life Bulletins by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ ESF. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. VOLUME 4 OCTOBER, 1926 NUMBER 1 Roosevelt Wild Life Bulletin OF THE Roosevelt Wild Life Forest Experiment Station OF The New York State College of Forestry AT Syracuse University RELATION OF BIRDS TO WOODLOTS CONTENTS OF ROOSEVELT WILD LIFE BULLETIN (To obtain these publications see announcement on back of title page.) Roosevelt Wild Life Bulletin, Vol. i, No. i. December, 192 1. 1. Foreword Dr. George Bird Grinnell. 2. Roosevelt Wild Life State Memorial Dr. Charles C. Adams. 3. Appropriateness and Appreciation of the Roosevelt Wild Life Memorial Dr. Charles C. Adams. 4. Suggestions for Research on North American Big Game and Fur- Bearing Animals Dr. Charles C. Adams. 5. Theodore Roosevelt Sir Harry H. Johnston. 6. Roosevelt's Part in Forestry Dr. -

Cankerworms Marion S

Published by Utah State University Extension and Utah Plant Pest Diagnostic Laboratory ENT-119-08 March 2020 Cankerworms Marion S. Murray Erin W. Hodgson IPM Project Leader Extension Entomology Specialist What You Should Know • Both spring and fall cankerworms occur sporadically in Utah, typically on a five to seven year cycle. • Larvae feed for six weeks in the spring and cause heavy defoliation in outbreak years. • Treatment is often not warranted for most years; however, using Bacillus thuringiensis or spinosad before larvae exceed 1/2 inch is an effective control option. ankerworms, also known as inchworms, are in 2 the order Lepidoptera and family Geometridae. Fig. 2. Fall cankerworm feeding damage. CGeometrid moth adults have slender bodies and relatively large, broad forewings (Figs. 1, 3). Both Hosts and Life Cycle fall, Alsophila pometaria, and spring, Paleacrita vernata, cankerworms occur in Utah, with the fall cankerworm Fall and spring cankerworm larvae feed on a wide being most common. Insect outbreaks are periodic variety of hardwood tree foliage including apple, ash, and concentrated in urban areas or near deciduous red and white oaks, maple (including boxelder), elm, woodlands, and can cause complete defoliation of cherry, linden, and honeylocust (Fig. 2). trees in early spring. Both cankerworm species are native to deciduous forests of North America, and Cankerworms have one generation per year. Eggs have many natural enemies that regulate outbreak hatch in early spring soon after bud break (about populations. Typically, the cankerworm population will 148-290 degree days after January 1, at 50˚F lower increase to an upper limit where it will remain for 2 to 3 developmental threshold). -

Maine Forest Service MAINE DEPARTMENT OF

Maine Forest Service ● MAINE DEPARTMENT OF CONSERVATION FALL CANKERWORM Alsophila pometaria (Harris) Insect and Disease Laboratory ● 168 State House Station ● 50 Hospital Street ● Augusta, Maine ● 043330168 Damage This important pest of forest and shade trees occurs generally throughout most of Northeastern America where it feeds on a variety of hardwoods. Damage is first noticed in early May when feeding by the tiny larvae known as "cankerworms," "loopers," "inchworms" or "measuring worms" on the opening buds and expanding leaves causes the foliage to be skeletonized. Later as the larvae mature all but the midrib (and veins) of leaves are devoured. Occasional outbreaks of this pest in Maine have caused severe defoliation of oak and elm. The outbreaks are most often localized and usually last three to four years before natural control factors cause the population to collapse. Trees subjected to two or more years of heavy defoliation may be seriously damaged, especially weaker trees or trees growing on poor sites. Hosts Its preferred hosts are oak, elm and apple, but it also occurs on maple, beech, ash, poplar, box elder, basswood, and cherry. Description and Habits The wingless, greyishbrown female cankerworm moths emerge from the duff with the onset of cold weather in October and November and crawl up the tree trunks. The male moth is greyishbrown with a one inch wing span. Males can often be seen flitting through infested stands during the day or warmer nights during hunting season. The females are not often seen. Females deposit their eggs in singlelayered compact masses of 100 or more on the bark of smaller branches and twigs of trees often high in the crown from October to early December. -

Insects That Feed on Trees and Shrubs

INSECTS THAT FEED ON COLORADO TREES AND SHRUBS1 Whitney Cranshaw David Leatherman Boris Kondratieff Bulletin 506A TABLE OF CONTENTS DEFOLIATORS .................................................... 8 Leaf Feeding Caterpillars .............................................. 8 Cecropia Moth ................................................ 8 Polyphemus Moth ............................................. 9 Nevada Buck Moth ............................................. 9 Pandora Moth ............................................... 10 Io Moth .................................................... 10 Fall Webworm ............................................... 11 Tiger Moth ................................................. 12 American Dagger Moth ......................................... 13 Redhumped Caterpillar ......................................... 13 Achemon Sphinx ............................................. 14 Table 1. Common sphinx moths of Colorado .......................... 14 Douglas-fir Tussock Moth ....................................... 15 1. Whitney Cranshaw, Colorado State University Cooperative Extension etnomologist and associate professor, entomology; David Leatherman, entomologist, Colorado State Forest Service; Boris Kondratieff, associate professor, entomology. 8/93. ©Colorado State University Cooperative Extension. 1994. For more information, contact your county Cooperative Extension office. Issued in furtherance of Cooperative Extension work, Acts of May 8 and June 30, 1914, in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, -

Influence of Habitat and Bat Activity on Moth Community Composition and Seasonal Phenology Across Habitat Types

INFLUENCE OF HABITAT AND BAT ACTIVITY ON MOTH COMMUNITY COMPOSITION AND SEASONAL PHENOLOGY ACROSS HABITAT TYPES BY MATTHEW SAFFORD THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Entomology in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2018 Urbana, Illinois Advisor: Assistant Professor Alexandra Harmon-Threatt, Chair and Director of Research ABSTRACT Understanding the factors that influence moth diversity and abundance is important for monitoring moth biodiversity and developing conservation strategies. Studies of moth habitat use have primarily focused on access to host plants used by specific moth species. How vegetation structure influences moth communities within and between habitats and mediates the activity of insectivorous bats is understudied. Previous research into the impact of bat activity on moths has primarily focused on interactions in a single habitat type or a single moth species of interest, leaving a large knowledge gap on how habitat structure and bat activity influence the composition of moth communities across habitat types. I conducted monthly surveys at sites in two habitat types, restoration prairie and forest. Moths were collected using black light bucket traps and identified to species. Bat echolocation calls were recorded using ultrasonic detectors and classified into phonic groups to understand how moth community responds to the presence of these predators. Plant diversity and habitat structure variables, including tree diameter at breast height, ground cover, and vegetation height were measured during summer surveys to document how differences in habitat structure between and within habitats influences moth diversity. I found that moth communities vary significantly between habitat types. -

Forest Insect and Disease Conditions in the Rocky Mountain Region 1997-1999

Forest Insect and Disease Conditions in the Rocky Mountain Region 1997-1999 United States Renewable Rocky Department of Resources Mountain Agriculture Forest Health Region Management 2 FOREST INSECT AND DISEASE CONDITIONS IN THE ROCKY MOUNTAIN REGION 1997-1999 by The Forest Health Management Staff Edited by Jeri Lyn Harris, Michelle Frank, and Susan Johnson December 2001 USDA Forest Service Rocky Mountain Region Renewable Resources, Forest Health Management P.O. Box 25127 Lakewood, Colorado 80225-5127 Cover: Aerial photograph taken by Robert D. Averill on October 29, 1997, just days after a blowdown event occurred on the Routt National Forest. The picture was taken looking east toward a blowdown area that straddles both the Mt. Zirkel Wilderness and the Routt National Forest. “The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, or marital or family status. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternate means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326-W, Whitten Building, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call (202) 720-5964 (voice and TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity employer.” Maps in this product are reproduced from geospatial information prepared by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. GIS data and product accuracy may vary. -

Impacts of Native and Non-Native Plants on Urban Insect Communities: Are Native Plants Better Than Non-Natives?

Impacts of Native and Non-native plants on Urban Insect Communities: Are Native Plants Better than Non-natives? by Carl Scott Clem A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Auburn University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science Auburn, Alabama December 12, 2015 Key Words: native plants, non-native plants, caterpillars, natural enemies, associational interactions, congeneric plants Copyright 2015 by Carl Scott Clem Approved by David Held, Chair, Associate Professor: Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology Charles Ray, Research Fellow: Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology Debbie Folkerts, Assistant Professor: Department of Biological Sciences Robert Boyd, Professor: Department of Biological Sciences Abstract With continued suburban expansion in the southeastern United States, it is increasingly important to understand urbanization and its impacts on sustainability and natural ecosystems. Expansion of suburbia is often coupled with replacement of native plants by alien ornamental plants such as crepe myrtle, Bradford pear, and Japanese maple. Two projects were conducted for this thesis. The purpose of the first project (Chapter 2) was to conduct an analysis of existing larval Lepidoptera and Symphyta hostplant records in the southeastern United States, comparing their species richness on common native and alien woody plants. We found that, in most cases, native plants support more species of eruciform larvae compared to aliens. Alien congener plant species (those in the same genus as native species) supported more species of larvae than alien, non-congeners. Most of the larvae that feed on alien plants are generalist species. However, most of the specialist species feeding on alien plants use congeners of native plants, providing evidence of a spillover, or false spillover, effect. -

Fall Cankerworm William M

Forest Insect & Disease Leaflet 182 April 2013 U.S. Department of Agriculture • Forest Service Fall Cankerworm William M. Ciesla 1 and Christopher Asaro 2 Fall cankerworm, Alsophila pometaria to Georgia and west to California, (Harris), is an insect that feeds on the Colorado, Missouri, Montana, New foliage of many species of broadleaf Mexico and Utah. trees. It is native to North America and populations periodically build to Larvae feed on a wide range of broad- outbreak levels that cause extensive leaf trees and smaller woody plants defoliation. This insect is a member of including apple, Malus pumila, ash, a large family of moths known as the Fraxinus spp., basswood, Tilia spp., Geometridae. The larvae are common- beech, Fagus grandifolia, cherry, ly referred to as “loopers, spanworms, Prunus spp., elm, Ulmus spp., hickory, inchworms or measuring worms.” Carya spp., maple, Acer spp. and many These names derive from their unique species of oaks, Quercus spp. Oaks way of locomotion. Geometrid lar- vae have only two functional pairs of prolegs. They clasp their front legs on a leaf or branch and draw up with the prolegs on the hind end. This causes the thoracic and abdominal segments to form an arch (Figure 1). They then reach out again with their thoracic legs. This gives the impression that they are measuring as they move about. Distribution and Hosts Fall cankerworm is found from the Maritime Provinces of Canada Figure 1. Mature fall cankerworm larva in a classic west to Alberta, throughout the “looper” position. Note reduced proleg on fifth eastern United States from Maine abdominal segment. -

Lifecycle of Cankerworms

Cankerworms are common pests of shade trees such as elm, apple, hackberry, maple, Basswood, hickory, box elder, black cherry, beech, birch, and many others. They are also known as inchworms or loopers due to their distinctive “looping” motion. Cankerworms have their own natural cycles of periodical outbreaks (for 2-7 years) followed by a period of low population (for 13 to 18 years). During their period of abundance, they can cause major defoliation, branch dieback, and death of trees. This is the reason why they need to be controlled as soon as they are detected. What are Cankerworms? Cankerworms have two species; fall cankerworms and spring cankerworms. • The fall species (Alsophila pometaria) have three pairs of prolegs and they lay their eggs in late fall and winter. • The spring species (Paleacrita vernata) have two pairs of prolegs and they lay their eggs in early spring. Spring and fall cankerworm look very similar to each other. The best way to differentiate them is to count their prolegs. Fully-grown females of both species are wingless. They are greyish brown in color and measure about 10-12 mm in length. The male cankerworms measure 25 mm in length and have greyish brown wings with irregular white bands. The larvae of both species also look very similar. Mature larvae are light green to dark brown in color. Light green caterpillars often have white lines running down their body. The dark brown ones have black stripes. Lifecycle of Cankerworms This pest has one generation per year. The lifecycle of both spring and fall species is almost same. -

US EPA, Pesticide Product Label, VBC -60397,02/10/2015

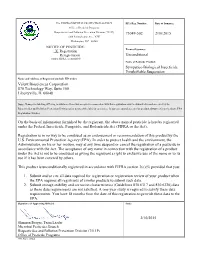

U.S. ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY EPA Reg. Number: Date of Issuance: Office of Pesticide Programs Biopesticides and Pollution Prevention Division (7511P) 73049-502 2/10/2015 1200 Pennsylvania Ave., N.W. Washington, D.C. 20460 NOTICE OF PESTICIDE: Term of Issuance: X Registration Reregistration Unconditional (under FIFRA, as amended) Name of Pesticide Product: Sympatico Biological Insecticide Emulsifiable Suspension Name and Address of Registrant (include ZIP Code): Valent Biosciences Corporation 870 Technology Way, Suite 100 Libertyville, IL 60048 Note: Changes in labeling differing in substance from that accepted in connection with this registration must be submitted to and accepted by the Biopesticides and Pollution Prevention Division prior to use of the label in commerce. In any correspondence on this product, always refer to the above EPA Registration Number. On the basis of information furnished by the registrant, the above named pesticide is hereby registered under the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA or the Act). Registration is in no way to be construed as an endorsement or recommendation of this product by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). In order to protect health and the environment, the Administrator, on his or her motion, may at any time suspend or cancel the registration of a pesticide in accordance with the Act. The acceptance of any name in connection with the registration of a product under the Act is not to be construed as giving the registrant a right to exclusive use of the name or to its use if it has been covered by others. This product is unconditionally registered in accordance with FIFRA section 3(c)(5) provided that you: 1.