Life in the Medieval University Cambridge University Press

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

31Higher Education

Educación ess Superior y Sociedad Higher Education in the Caribbean 311 Instituto Internacional de Unesco para la Educación Superior en América Latina y el Caribe (IESALC), 2019-II Educación Superior y Sociedad (ESS) Nueva etapa Vol. 31 ISSN 07981228 (formato impreso) ISSN 26107759 (formato digital) Publicación semestral EQUIPO DE PRODUCCIÓN Débora Ramos Ayumarí Rodríguez Enrique Ravelo José Antonio Vargas Sara Maneiro Yara Bastidas Zulay Gómez José Quinteiro Yeritza Rodríguez CORRECCIÓN DE ESTILO Annette Insanally DIAGRAMACIÓN Pedro Juzgado A. TRADUCCIÓN Yara Bastidas Apartado Postal Nª 68.394 Caracas 1062-A, Venezuela Teléfono: +58 - 212 - 2861020 E-mail: [email protected] / [email protected] 2 CONSEJO EDITORIAL INTERNACIONAL • Rectores Dra. Alta Hooker Rectora de la Universidad de las Regiones Autónomas de la Costa Caribe Nicaragüense Dr. Benjamín Scharifker Podolsky Rector Metropolitana, Venezuela Dr. Emilio Rodríguez Ponce Rector de la Universidad de Tarapacá, Chile Dr. Francisco Herrera Rector Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Honduras Dr. Ricardo Hidalgo Ottolenghi Rector UTE Padre D. Ramón Alfredo de la Cruz Baldera Pontificia Universidad Católica Madre y Maestra, República Dominicana Dr. Rita Elena Añez Rectora Universidad Nacional Experimental Politécnica “Antonio José de Sucre” Dr. Waldo Albarracín Rector Universidade Mayor de San Andrés, Bolivia Dr. Freddy Álvarez González Rector de la Universidad Nacional de Educación -UNAE Dra. Sara Deifilia Ladrón de Guevara González Universidad Veracruzana, México • Expertos e investigadores -

One, Holy, Catholic, and Apostolic: a History of the Church in the Middle Ages

ONE , H OLY , CATHOLIC , AND APOSTOLIC : A H ISTORY OF THE CHURCH IN THE MIDDLE AGES COURSE GUIDE Professor Thomas F. Madden SAINT LOUIS UNIVERSITY One, Holy, Catholic, and Apostolic: A History of the Church in the Middle Ages Professor Thomas F. Madden Saint Louis University Recorded Books ™ is a trademark of Recorded Books, LLC. All rights reserved. One, Holy, Catholic, and Apostolic: A History of the Church in the Middle Ages Professor Thomas F. Madden Executive Producer John J. Alexander Executive Editor Donna F. Carnahan RECORDING Producer - David Markowitz Director - Matthew Cavnar COURSE GUIDE Editor - James Gallagher Contributing Editor - Karen Sparrough Design - Edward White Lecture content ©2006 by Thomas F. Madden Course guide ©2006 by Recorded Books, LLC 72006 by Recorded Books, LLC Cover image: Basilica of Notre Dame Cathedral, Paris © Clipart.com #UT095 ISBN: 978-1-4281-3777-6 All beliefs and opinions expressed in this audio/video program and accompanying course guide are those of the author and not of Recorded Books, LLC, or its employees. Course Syllabus One, Holy, Catholic, and Apostolic: A History of the Church in the Middle Ages About Your Professor ................................................................................................... 4 Introduction ................................................................................................................... 5 Lecture 1 Birth of the Medieval Church ................................................................. 6 Lecture 2 The Church in an Age of -

Opportunities for Teaching and Studying Medicine in Medieval Portugal Before the Foundation of the University of Lisbon (1290)(*)

Opportunities for Teaching and Studying Medicine in Medieval Portugal before the Foundation of the University of Lisbon (1290)(*) IONA McCLEERY (**) ABSTRACT This paper discusses where Portuguese physicians studied medicine. The careers of two thirteenth-century physicians, Petrus Hispanus and Giles of Santarém, indicate that the Portuguese travelled abroad to study in Montpellier or Paris. But it is also possible that there were opportunities for study in Portugal itself. Particularly significant in this respect is the tradition of medical teaching associated with the Augustinian house of Santa Cruz in Coimbra and the reference to medical texts found in Coimbra archives. From these sources it can be shown that there was a suitable environment for medical study in medieval Portugal, encouraging able students to further their medical interests elsewhere. BIBLID [0211-9536(2000) 20; 305-329] Fecha de aceptación: 8 de marzo de 1998 (*) A version of this paper was delivered at the «Medical Teaching» conference at King’s College, Cambridge on 7-9 January 1998. I would like to thank Roger French for inviting me to take part in the conference, and Cornelius O’Boyle, Michael McVaugh, Tessa Webber, Charles Burnett, Miguel de Asua, Klaus-Dietrich Fischer, and Tiziana Pesenti for their comments and encouragement during the conference. Further thanks go to my friends and office mates Julie Kerr, Angus Stewart, Haki Antonsson and Björn Weiler, who have kept me going throughout my studies. Finally, I am very grateful to my supervisor, Simone Macdougall, who read a draft of this paper at short notice, and whose advice and suggestions are greatly appreciated. -

Liberal Arts Colleges in American Higher Education

Liberal Arts Colleges in American Higher Education: Challenges and Opportunities American Council of Learned Societies ACLS OCCASIONAL PAPER, No. 59 In Memory of Christina Elliott Sorum 1944-2005 Copyright © 2005 American Council of Learned Societies Contents Introduction iii Pauline Yu Prologue 1 The Liberal Arts College: Identity, Variety, Destiny Francis Oakley I. The Past 15 The Liberal Arts Mission in Historical Context 15 Balancing Hopes and Limits in the Liberal Arts College 16 Helen Lefkowitz Horowitz The Problem of Mission: A Brief Survey of the Changing 26 Mission of the Liberal Arts Christina Elliott Sorum Response 40 Stephen Fix II. The Present 47 Economic Pressures 49 The Economic Challenges of Liberal Arts Colleges 50 Lucie Lapovsky Discounts and Spending at the Leading Liberal Arts Colleges 70 Roger T. Kaufman Response 80 Michael S. McPherson Teaching, Research, and Professional Life 87 Scholars and Teachers Revisited: In Continued Defense 88 of College Faculty Who Publish Robert A. McCaughey Beyond the Circle: Challenges and Opportunities 98 for the Contemporary Liberal Arts Teacher-Scholar Kimberly Benston Response 113 Kenneth P. Ruscio iii Liberal Arts Colleges in American Higher Education II. The Present (cont'd) Educational Goals and Student Achievement 121 Built To Engage: Liberal Arts Colleges and 122 Effective Educational Practice George D. Kuh Selective and Non-Selective Alike: An Argument 151 for the Superior Educational Effectiveness of Smaller Liberal Arts Colleges Richard Ekman Response 172 Mitchell J. Chang III. The Future 177 Five Presidents on the Challenges Lying Ahead The Challenges Facing Public Liberal Arts Colleges 178 Mary K. Grant The Importance of Institutional Culture 188 Stephen R. -

Science and Nature in the Medieval Ecological Imagination Jessica Rezunyk Washington University in St

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations Arts & Sciences Winter 12-15-2015 Science and Nature in the Medieval Ecological Imagination Jessica Rezunyk Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds Recommended Citation Rezunyk, Jessica, "Science and Nature in the Medieval Ecological Imagination" (2015). Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 677. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds/677 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Arts & Sciences at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS Department of English Dissertation Examination Committee: David Lawton, Chair Ruth Evans Joseph Loewenstein Steven Meyer Jessica Rosenfeld Science and Nature in the Medieval Ecological Imagination by Jessica Rezunyk A dissertation presented to the Graduate School of Arts & Sciences of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2015 St. Louis, Missouri © 2015, Jessica Rezunyk Table of Contents List of Figures……………………………………………………………………………. iii Acknowledgments…………………………………………………………………………iv Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………vii Chapter 1: (Re)Defining -

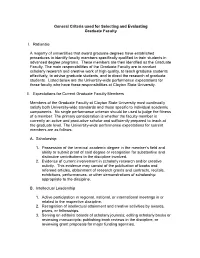

General Criteria Used for Selecting and Evaluating Graduate Faculty I

General Criteria used for Selecting and Evaluating Graduate Faculty I. Rationale A majority of universities that award graduate degrees have established procedures to identify faculty members specifically qualified to train students in advanced degree programs. These members are then identified as the Graduate Faculty. The main responsibilities of the Graduate Faculty are to conduct scholarly research and creative work of high quality, to teach graduate students effectively, to advise graduate students, and to direct the research of graduate students. Listed below are the University-wide performance expectations for those faculty who have these responsibilities at Clayton State University. II. Expectations for Current Graduate Faculty Members Members of the Graduate Faculty at Clayton State University must continually satisfy both University-wide standards and those specific to individual academic components. No single performance criterion should be used to judge the fitness of a member. The primary consideration is whether the faculty member is currently an active and productive scholar and sufficiently prepared to teach at the graduate level. The University-wide performance expectations for current members are as follows: A. Scholarship 1. Possession of the terminal academic degree in the member’s field and ability to submit proof of said degree or recognition for substantive and distinctive contributions to the discipline involved. 2. Evidence of current involvement in scholarly research and/or creative activity. This evidence may consist of the publication of books and refereed articles, obtainment of research grants and contracts, recitals, exhibitions, performances, or other demonstrations of scholarship appropriate to the discipline. B. Intellectual Leadership 1. Active participation in regional, national, or international meetings in or related to the respective discipline. -

Decoding the Statutes of Gregory IX for the University of Paris 1231

Decoding The Statutes of Gregory IX for the University of Paris 1231 What had motivated Gregory IX's interest in the University of Paris? The Statutes of Gregory IX 1 for the University of Paris 1231 2 define the new rights and privileges of the teachers and students and help stopping the exodus of the teachers and students from the University, particularly for Oxford. It serves to ratify with immediacy as per a perceived denial 3 of justice, which had been sanctioned by Queen Blanche in 1229 and resulted in the teachers’ 2-year suspension of their teaching for the courses in retaliation. 4 Well-versed in the political situation of Europe 5, Pope Gregory IX’s 6 worries seem well-founded an exodus of teachers and students from The University of Paris does happen before the enactment of The Statutes. The teacher-student exodus in Europe has always been a widespread phenomenon.7 Gregory XI’s bestow on students’ right and privileges may well be his being a past student of The University of Paris, but his strong stance in anti-hereticism might point to his intended control over the teachers and students 8 carries much water. While no ulterior motive could justly be implied to Gregory IX, as a nephew of the 1 Based on the translation from Dana C. Munro, trans., University of Pennsylvania Translations and Reprints , (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1897), Vol. II: No. 3, pp. 7-11 2 Hereafter called The Statutes. 3 The trouble originated in a quarrel in an inn in Paris which developed into a fight between the students and the citizens of Paris. -

Erasmus + Agreement

Annex to Erasmus+ Inter-Institutional Agreement Institutional Factsheet 1. Institutional Information 1.1. Institutional details Name of the institution Université Paris Diderot – Paris 7 Erasmus Code F PARIS007 EUC Nr. 28258 Institution website http://www.univ-paris-diderot.fr Online course catalogue / 1.2. Main contacts Contact person Jan DOUAT* Responsibility Central management of the Erasmus+ program Contact person for Erasmus+ partners Contact details Phone: +33 1 57 27 59 53 - Fax: +33 1 57 27 55 07 Email: [email protected] Contact person Floriane THOREZ* Responsibility Contact person for incoming students / Internships Contact details Phone: +33 1 57 27 55 05 - Fax: +33 1 57 27 55 07 - Email: [email protected] Contact person Valérie BEAUDOIN* Responsibility Contact person for outgoing students Contact details Phone: +33 1 57 27 55 34 - Fax: +33 1 57 27 55 07 - Email: [email protected] The email address will remain identical even in the case of a turnover Annex to Erasmus + Inter-Institutional Agreement | Institutional Factsheet Page 1 / 4 2. Detailed requirements and additional information 2.1. Recommended language skills Following agreement with our institution, the sending institution is responsible for providing support to its nominated candidates so that they can have the recommended language skills at the start of the study or teaching period: COURSES ARE TAUGHT IN FRENCH Type of mobility Subject area Language(s) of instruction Recommended language of instruction -

Curriculum Vitae Voula Tsouna

1 Curriculum Vitae Voula Tsouna Department of Philosophy, University of California Santa Barbara, CA 93106-3090 [email protected] Place of Birth: Athens, Greece Nationality: Greek (EU) & USA Languages: Ancient Greek, Latin, French (fluent), English (fluent), Modern Greek (fluent), Italian (competent), German (reading) AREA OF SPECIALIZATION Ancient Philosophy AREAS OF COMPETENCE Siècle des Lumières (French Enlightment), Early Modern Philosophy, topics in Epistemology, Moral Psychology, and Ethics. EDUCATION 1988 PhD (Thèse de doctorat), Ancient Philosophy, University of Paris X 1984-86 Doctoral Research, fully enrolled graduate student at the University of Cambridge, King’s College 1984 Diplôme d’Études Approfondies (DEA, equivalent to the MA), Ancient Philosophy, University of Paris X 1983 Bachelor of Arts in Philosophy summa cum laude (Πτυχεῖον summa cum laude), Philosophy, University of Athens ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS 2006–present University of California at Santa Barbara, Full Professor 2000–2006 University of California at Santa Barbara, Associate Professor 1997–2000 University of California at Santa Barbara, Assistant Professor 1997 (Winter) University of California at Santa Barbara, Visiting Assistant Professor of Philosophy 2010 (Spring) University of Crete, Holder of the Michelis Chair in Aesthetics at the Department of Philosophy and Social Studies 1994–1996 Pomona College, Visiting Assistant Professor 1992–1993 University of Glasgow, Scotland, Research Fellow 1991–1992 California State University at San Bernardino, Lecturer -

Liberal Arts Education and Information Technology

VIEWPOINT Liberal Arts Education and Information Technology: Time for Another Renewal Liberal arts colleges must accommodate the powerful changes that are taking place in the way people communicate and learn by Todd D. Kelley hree significant societal trends and that institutional planning and deci- Five principal reasons why the future will most certainly have a broad sion making must reflect the realities of success of liberal arts colleges is tied to Timpact on information services rapidly changing information technol- their effective use of information tech- and higher education for some time to ogy. Boards of trustees and senior man- nology are: come: agement must not delay in examining • Liberal arts colleges have an obliga- • the increasing use of information how these changes in society will impact tion to prepare their students for life- technology (IT) for worldwide com- their institutions, both negatively and long learning and for the leadership munications and information cre- positively, and in embracing the idea roles they will assume when they ation, storage, and retrieval; that IT is integral to fulfilling their liberal graduate. • the continuing rapid change in the arts missions in the future. • Liberal arts colleges must demon- development, maturity, and uses of (2) To plan and support technological strate the use of the most significant information technology itself; and change effectively, their colleges must approaches to problem solving and • the growing need in society for have sufficient high-quality information communications to have emerged skilled workers who can understand services staff and must take a flexible and since the invention of the printing and take advantage of the new meth- creative approach to recruiting and press and movable type. -

Dr. Jeffrey Dirk Wilson CV

Photo credit: Robert M. West Jeffrey Dirk Wilson “For natures such as mine, a journey is invaluable: it enlivens, corrects, teaches, and cultivates.” Johann Wolfgang von Goethe 1 Jeffrey Dirk Wilson: CV—May 20, 2021 With tomatoes on my right, cucumbers on my left, and apples behind me. “The greatest service which can be rendered any country is to add an useful plant to its culture.” Thomas Jefferson 2 Jeffrey Dirk Wilson: CV—May 20, 2021 Jeffrey Dirk Wilson 103c Aquinas Hall School of Philosophy The Catholic University of America 410.452.8465 [email protected] ______________________________________________________________________________ Areas of Specialization: Areas of Competence: Ancient Greek Philosophy Art and Language Classical Metaphysics Epistemology Political Philosophy Ethics Human Nature Academic Experience: Collegiate Associate Professor (formerly Clinical Associate Professor), The School of Philosophy of the Catholic University of America; courses taught: “The Classical Mind,” “The Modern Mind,” “Metaphysics,” “Philosophy of Art” “Philosophy of Knowledge,” “Philosophy of Human Nature,” “Philosophy of Natural Right and Natural Law,” “Political Philosophy,” “Philosophy of Language” “Senior Seminar: The Metaphysics of Beauty”: 2015-present. Non-Residential Fellow, Instituto de Filosofía Edith Stein: 2021-present. Clinical Assistant Professor, The School of Philosophy of The Catholic University of America: 2009-2015. Adjunct Clinical Assistant Professor, St. Mary’s Seminary and University, School of Theology; course taught: “Metaphysics”: winter-spring 2013. Lecturer (full-time), Mount St. Mary’s University, Emmitsburg, Maryland; courses taught: “From Cosmos to Citizen,” “From Self to Society,” “Moral Philosophy”: 2007-2009. Lecturer, The School of Philosophy, The Catholic University of America, Washington, D.C.; courses taught: “The Classical Mind,” “The Modern Mind”: 2005-2006, fall 2006.” Member of the Library Committee for the School of Philosophy, The Catholic University of America, Washington, D.C.: 2005-2006. -

The Magisterium of the Faculty of Theology of Paris in the Seventeenth Century

Theological Studies 53 (1992) THE MAGISTERIUM OF THE FACULTY OF THEOLOGY OF PARIS IN THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY JACQUES M. GRES-GAYER Catholic University of America S THEOLOGIANS know well, the term "magisterium" denotes the ex A ercise of teaching authority in the Catholic Church.1 The transfer of this teaching authority from those who had acquired knowledge to those who received power2 was a long, gradual, and complicated pro cess, the history of which has only partially been written. Some sig nificant elements of this history have been overlooked, impairing a full appreciation of one of the most significant semantic shifts in Catholic ecclesiology. One might well ascribe this mutation to the impetus of the Triden tine renewal and the "second Roman centralization" it fostered.3 It would be simplistic, however, to assume that this desire by the hier archy to control better the exposition of doctrine4 was never chal lenged. There were serious resistances that reveal the complexity of the issue, as the case of the Faculty of Theology of Paris during the seventeenth century abundantly shows. 1 F. A. Sullivan, Magisterium (New York: Paulist, 1983) 181-83. 2 Y. Congar, 'Tour une histoire sémantique du terme Magisterium/ Revue des Sci ences philosophiques et théologiques 60 (1976) 85-98; "Bref historique des formes du 'Magistère' et de ses relations avec les docteurs," RSPhTh 60 (1976) 99-112 (also in Droit ancien et structures ecclésiales [London: Variorum Reprints, 1982]; English trans, in Readings in Moral Theology 3: The Magisterium and Morality [New York: Paulist, 1982] 314-31). In Magisterium and Theologians: Historical Perspectives (Chicago Stud ies 17 [1978]), see the remarks of Y.