A Newsletter for Graduates of the Program of Liberal Studies Vol VI

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liberal Arts Colleges in American Higher Education

Liberal Arts Colleges in American Higher Education: Challenges and Opportunities American Council of Learned Societies ACLS OCCASIONAL PAPER, No. 59 In Memory of Christina Elliott Sorum 1944-2005 Copyright © 2005 American Council of Learned Societies Contents Introduction iii Pauline Yu Prologue 1 The Liberal Arts College: Identity, Variety, Destiny Francis Oakley I. The Past 15 The Liberal Arts Mission in Historical Context 15 Balancing Hopes and Limits in the Liberal Arts College 16 Helen Lefkowitz Horowitz The Problem of Mission: A Brief Survey of the Changing 26 Mission of the Liberal Arts Christina Elliott Sorum Response 40 Stephen Fix II. The Present 47 Economic Pressures 49 The Economic Challenges of Liberal Arts Colleges 50 Lucie Lapovsky Discounts and Spending at the Leading Liberal Arts Colleges 70 Roger T. Kaufman Response 80 Michael S. McPherson Teaching, Research, and Professional Life 87 Scholars and Teachers Revisited: In Continued Defense 88 of College Faculty Who Publish Robert A. McCaughey Beyond the Circle: Challenges and Opportunities 98 for the Contemporary Liberal Arts Teacher-Scholar Kimberly Benston Response 113 Kenneth P. Ruscio iii Liberal Arts Colleges in American Higher Education II. The Present (cont'd) Educational Goals and Student Achievement 121 Built To Engage: Liberal Arts Colleges and 122 Effective Educational Practice George D. Kuh Selective and Non-Selective Alike: An Argument 151 for the Superior Educational Effectiveness of Smaller Liberal Arts Colleges Richard Ekman Response 172 Mitchell J. Chang III. The Future 177 Five Presidents on the Challenges Lying Ahead The Challenges Facing Public Liberal Arts Colleges 178 Mary K. Grant The Importance of Institutional Culture 188 Stephen R. -

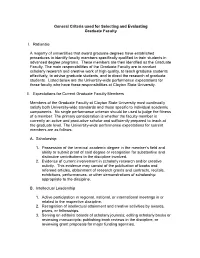

General Criteria Used for Selecting and Evaluating Graduate Faculty I

General Criteria used for Selecting and Evaluating Graduate Faculty I. Rationale A majority of universities that award graduate degrees have established procedures to identify faculty members specifically qualified to train students in advanced degree programs. These members are then identified as the Graduate Faculty. The main responsibilities of the Graduate Faculty are to conduct scholarly research and creative work of high quality, to teach graduate students effectively, to advise graduate students, and to direct the research of graduate students. Listed below are the University-wide performance expectations for those faculty who have these responsibilities at Clayton State University. II. Expectations for Current Graduate Faculty Members Members of the Graduate Faculty at Clayton State University must continually satisfy both University-wide standards and those specific to individual academic components. No single performance criterion should be used to judge the fitness of a member. The primary consideration is whether the faculty member is currently an active and productive scholar and sufficiently prepared to teach at the graduate level. The University-wide performance expectations for current members are as follows: A. Scholarship 1. Possession of the terminal academic degree in the member’s field and ability to submit proof of said degree or recognition for substantive and distinctive contributions to the discipline involved. 2. Evidence of current involvement in scholarly research and/or creative activity. This evidence may consist of the publication of books and refereed articles, obtainment of research grants and contracts, recitals, exhibitions, performances, or other demonstrations of scholarship appropriate to the discipline. B. Intellectual Leadership 1. Active participation in regional, national, or international meetings in or related to the respective discipline. -

Liberal Arts Education and Information Technology

VIEWPOINT Liberal Arts Education and Information Technology: Time for Another Renewal Liberal arts colleges must accommodate the powerful changes that are taking place in the way people communicate and learn by Todd D. Kelley hree significant societal trends and that institutional planning and deci- Five principal reasons why the future will most certainly have a broad sion making must reflect the realities of success of liberal arts colleges is tied to Timpact on information services rapidly changing information technol- their effective use of information tech- and higher education for some time to ogy. Boards of trustees and senior man- nology are: come: agement must not delay in examining • Liberal arts colleges have an obliga- • the increasing use of information how these changes in society will impact tion to prepare their students for life- technology (IT) for worldwide com- their institutions, both negatively and long learning and for the leadership munications and information cre- positively, and in embracing the idea roles they will assume when they ation, storage, and retrieval; that IT is integral to fulfilling their liberal graduate. • the continuing rapid change in the arts missions in the future. • Liberal arts colleges must demon- development, maturity, and uses of (2) To plan and support technological strate the use of the most significant information technology itself; and change effectively, their colleges must approaches to problem solving and • the growing need in society for have sufficient high-quality information communications to have emerged skilled workers who can understand services staff and must take a flexible and since the invention of the printing and take advantage of the new meth- creative approach to recruiting and press and movable type. -

The Magisterium of the Faculty of Theology of Paris in the Seventeenth Century

Theological Studies 53 (1992) THE MAGISTERIUM OF THE FACULTY OF THEOLOGY OF PARIS IN THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY JACQUES M. GRES-GAYER Catholic University of America S THEOLOGIANS know well, the term "magisterium" denotes the ex A ercise of teaching authority in the Catholic Church.1 The transfer of this teaching authority from those who had acquired knowledge to those who received power2 was a long, gradual, and complicated pro cess, the history of which has only partially been written. Some sig nificant elements of this history have been overlooked, impairing a full appreciation of one of the most significant semantic shifts in Catholic ecclesiology. One might well ascribe this mutation to the impetus of the Triden tine renewal and the "second Roman centralization" it fostered.3 It would be simplistic, however, to assume that this desire by the hier archy to control better the exposition of doctrine4 was never chal lenged. There were serious resistances that reveal the complexity of the issue, as the case of the Faculty of Theology of Paris during the seventeenth century abundantly shows. 1 F. A. Sullivan, Magisterium (New York: Paulist, 1983) 181-83. 2 Y. Congar, 'Tour une histoire sémantique du terme Magisterium/ Revue des Sci ences philosophiques et théologiques 60 (1976) 85-98; "Bref historique des formes du 'Magistère' et de ses relations avec les docteurs," RSPhTh 60 (1976) 99-112 (also in Droit ancien et structures ecclésiales [London: Variorum Reprints, 1982]; English trans, in Readings in Moral Theology 3: The Magisterium and Morality [New York: Paulist, 1982] 314-31). In Magisterium and Theologians: Historical Perspectives (Chicago Stud ies 17 [1978]), see the remarks of Y. -

OAKWOOD UNIVERSITY Faculty Handbook

FACULTY HANDBOOK OAKWOOD UNIVERSITY Faculty Handbook (Revised 2008) Faculty Handbook Page 1 FACULTY HANDBOOK Table of Contents Section I General Administration Information Oakwood University Mission Statement ........................................................................................... 5 Historic Glimpses .............................................................................................................................. 5 Accreditation ...................................................................................................................................... 5 Affirmative Action and Religious Institution Exemption .................................................................. 6 Sexual Harassment ............................................................................................................................. 6 Drug-free Environment ...................................................................................................................... 7 Establishment and Dissolution of Departments and Majors .............................................................. 8 Section II Policies Governing Faculty Functions Faculty Classifications ...................................................................................................................... 10 Academic Rank ................................................................................................................................. 11 Promotions ....................................................................................................................................... -

Development of a Curriculum in the Early American Colleges Author(S): Joe W

The Development of a Curriculum in the Early American Colleges Author(s): Joe W. Kraus Source: History of Education Quarterly, Vol. 1, No. 2, (Jun., 1961), pp. 64-76 Published by: History of Education Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/367641 Accessed: 02/05/2008 14:31 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=hes. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We enable the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org THE DEVELOPMENT OF A CURRICULUM IN THE EARLY AMERICAN COLLEGES Joe W. Kraus The early American colleges were smaller and poorer counter- parts of the universities of Great Britain, rather than indigenous institutions, and the mother country was the source of their cur- riculum. -

Recommendations of the Faculty Task Force for the Restructuring of the Division of Academic Affairs

FTF May 15, 2013 Recommendations of the Faculty Task Force For the Restructuring of the Division of Academic Affairs Introduction On March 1, 2013, the Provost, pursuant to the Chancellor’s request, formed two Task Forces to consider the optimal structure for the Academic Affairs Division: a Chairs Task Force and a Faculty Task Force. The Executive Committee of the Faculty Senate selected the members of the Faculty Task Force from nominations submitted by the colleges and key councils/committees of the Faculty Senate. The members were: Adriana Lopez-Ramirez - College of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences Cynthia Daily - College of Business Kent Layton - College of Education Shannon Collier-Tenison - College of Professional Studies Matthew Gifford - College of Science Steve Minsker - College of Engineering and Information Technology John DiPippa - Law School (Chair) Karen Russ - Ottenheimer Library Thomas Clifton - Undergraduate Council Amanda Nolen - Graduate Council Andrew Wright - Faculty Senate Executive Committee Elisabeth Sherwin - Planning and Finance Committee Sarah Beth Estes – Academic Restructuring Liaison (non-voting member) Time Line The Task Forces were to review the existing Academic Affairs division structure and to recommend, by May 15, 2013 at least two new academic structures designed to: Enhance interdisciplinary collaboration to facilitate UALR’s timely response to the changing needs of the city, state and nation in terms of curricula, community engagement, and research. Implement an efficient academic structure that will result in cost savings allowing UALR to match available resources to strategic priorities. By April 23, 2013, the task forces submitted their preliminary recommendations to the Liaison who made them available to the campus community. -

The Status of Women Faculty in the Humanities and Social Sciences at Princeton University

The Status of Women Faculty in the Humanities and Social Sciences at Princeton University July 2005 Joan S. Girgus Special Assistant to the Dean of the Faculty Professor of Psychology Thanks to Bruce Draine (Astrophysical Sciences), Gilda Paul (Office of the Dean of the Faculty), Christina Paxson (Economics and the Woodrow Wilson School), and Virginia Zakian (Molecular Biology) for their help with the analyses, figures, and tables in this report, and Carolynne Lewis- Arévalo for her help with formatting and typing. The Status of Women Faculty in the Humanities and Social Sciences at Princeton University Executive Summary This report on The Status of Women Faculty in the Humanities and Social Sciences at Princeton parallels the report on The Status of Women Faculty in the Natural Sciences and Engineering that was issued in September 2003. The order of the topics and the time periods covered are identical in the two reports, in order to make it easier to think about the two reports in tandem. The following are the major points of the data on tenure-track women faculty in the Humanities and Social Sciences. The detailed data are contained within the report. • Representation of tenure-track women in the Humanities and Social Sciences Departments grew slowly, and not very steadily, over the decade between 1992 and 2002 (from 23.2% to 26.9%). In the Humanities, the percentage of tenured women increased from 17.3 % to 26.3%, while the percentage of women assistant professors actually declined from 50.0% to 41.0%. In the Social Sciences, there was a slight increase in the percentage of tenured women (from 15.7% to 17.6%) and a somewhat greater increase in the percentage of women assistant professors (from 25.9% to 34.0%). -

Student Power in Medieval Universities

• Student Power In Medieval Universities V. R. CARDOZIER Current student power efforts have precedent in medieval universities, pri marily at Bologna, which was a completely student-dominated university. The university government was composed of students only, except for the chancellor, a church appointee whose power was limited largely to awarding degrees. Professors were required to abide by student-approved regulations, to swear obedience to the (student) rector, and to follow procedures pre scribed by students in conduct of classes. Either by church or royal decree, students enjoyed privileges unknown today, such as freedom from taxation and military service, often freedom from arrest and trial in civil courts, and other considerations. URRENT A'ITEMPTS by university stu UNIVERSITY GOVERNMENT C dents to gain more control over their own affairs and over university govern Student power at Bologna evolved ment in general are not a new phenomenon. naturally from the circumstances under Their desire to influence curricula. course which the university developed. It began content, teaching methods, grading, selec as a collection of teachers who practiced tion and promotion of professors, to gain essentially as independent entrepreneurs. student representation on university gov Although the teachers formed guilds quite erning bodies, freedom from police inter early, these were informal and without vention in campus demonstrations, and power. complete self-determination of non-aca While almost all of the teachers were demic student life, all have precedents in Bolognese, most of the students were for medieval universities. eigners. To protect themselves from in The most complete student control of justices by the city and to provide other universities occurred at Bologna during services cooperatively, the students began the 13th and 14th centuries. -

Third Grade Faculty Bios

Third Grade Faculty Bios 3A Lead Teacher, Mr. Kratz My name is Jeremy Kratz, and this is my second year at Great Hearts Academies. I have five years of experience in the classroom in various capacities, and also have a background in insurance and mortgage banking. I grew up in northern Indiana and have lived in Arizona for 21 years. My wife Amy and I have two children here at Archway Trivium West, in 3rd and 5th grades. I enjoy hiking and the great outdoors, traveling with my family, history, grilling, and music. I look forward to my second year with Great Hearts and helping instill truth, beauty, and goodness into the lives of our scholars. Sincerely, Jeremy Kratz [email protected] 3A Teacher Assistant, Ms. Shannon My name is Maria Shannon and I have been at Archway Trivium West for five years. This will be my first year in 3rd grade. I have lived in Avondale for 19 years and I have three daughters. I love to cook, sew, read, and craft. It is my pleasure to work with your child this year. Sincerely, Maria Shannon [email protected] 3B Lead Teacher, Mrs. Manson I am delighted to begin my first year of teaching with Great Hearts this year. I grew up in Phoenix with a detour to Tacoma, WA where I attended University of Puget Sound. I received my BA in Spanish and a Masters in Teaching. I taught 2nd and 3rd grade for 8 years in Tacoma before our family moved back to Goodyear. I love to cook, spend time with my family, read, and craft. -

Carleton Letter

Carleton UNIVERSITY March 24'h, 2012 S.S. lyengar PhD Director and Ryder Professor School of Computing and Information Sciences FIU, 11200 SW 8th Street, Miami, Florida 33199, USA Dear Prof. lyengar, I am deeply honoured to have had the chance to discuss my past research on the Brooks-lyengar algorithm on Robust Distributed Sensing and its application in Linux Operating Systems, as discussed on the phone last week. As I mentioned, in 1993 I was a researcher in the field of Real-Time Operating Systems (with a focus on Real-Time scheduling). During that period of research I was able to define new RT scheduling algorithms, and I included these (and other RT techniques) in the first existing RT version of an open-source OS (RT-Minix). The MINIX operating system was extended with real-time services, ranging from A/D drivers to new scheduling algorithms and statistics collection. A testbed was constructed to tests several sensor replication techniques in order to implement and verify several robust sensing algorithms. As a result, new services enhancing fault tolerance for replicated sensors were also provided within the kernel. The resulting OS offers new fea- tures such as real-time task management (for both periodic or a periodic tasks), clock resolution handling, and sensor replication manipulate Using this workbench, we implemented different versions of the Brooks-lyengar algorithm for robust sensing, using inexact agreement and optimal region. The introduction of this new mechanism provided more accuracy and precision. These results were published in various papers and a book. My ideas were used shortly after by other researchers in the field, leading to the development of the first versions of RT-Linux. -

Marquette University Handbook for Full-Time Faculty

HANDBOOK FOR FULL-TIME FACULTY Current version approved 27 August 2013 last amended September 30, 2021 FROM THE PRESIDENT Marquette University, since opening its doors in 1881, has constantly pursued intellectual excellence with explicit attention to religious faith and moral values, encouragement and development of leadership skills, and the promotion of justice and faith through service to others. We want to help our students become leaders in our contemporary world, exemplary in their chosen academic and professional fields, and, most important, marked in their personal and professional lives by the Jesuit values we share with them. To remain faithful to this heritage and achieve our goals, we first and foremost depend upon talented and dedicated faculty members. Throughout our history, we have succeeded in attracting and retaining outstanding educators, and I am pleased that you are a member of our Marquette community. I thank you for the countless ways in which you enable the university, amid our vibrant and challenging urban environment, to provide quality undergraduate, graduate, and professional education in an atmosphere of care and faith. This handbook is designed to be a helpful source for answering questions you may have about Marquette University and its policies, helping make your work here satisfying and productive. May God bless all of us abundantly in our commitment to the advancement of knowledge within our respective disciplines and to the students whose lives we will positively guide both inside and outside the classroom. Best, Michael R. Lovell President MARQUETTE UNIVERSITY Office of the Provost FACULTY HANDBOOK TABLE OF CONTENTS I. University Objectives and Organization A.