THE LIBERAL ARTS at EVERGREEN Sam Schrager

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liberal Arts Colleges in American Higher Education

Liberal Arts Colleges in American Higher Education: Challenges and Opportunities American Council of Learned Societies ACLS OCCASIONAL PAPER, No. 59 In Memory of Christina Elliott Sorum 1944-2005 Copyright © 2005 American Council of Learned Societies Contents Introduction iii Pauline Yu Prologue 1 The Liberal Arts College: Identity, Variety, Destiny Francis Oakley I. The Past 15 The Liberal Arts Mission in Historical Context 15 Balancing Hopes and Limits in the Liberal Arts College 16 Helen Lefkowitz Horowitz The Problem of Mission: A Brief Survey of the Changing 26 Mission of the Liberal Arts Christina Elliott Sorum Response 40 Stephen Fix II. The Present 47 Economic Pressures 49 The Economic Challenges of Liberal Arts Colleges 50 Lucie Lapovsky Discounts and Spending at the Leading Liberal Arts Colleges 70 Roger T. Kaufman Response 80 Michael S. McPherson Teaching, Research, and Professional Life 87 Scholars and Teachers Revisited: In Continued Defense 88 of College Faculty Who Publish Robert A. McCaughey Beyond the Circle: Challenges and Opportunities 98 for the Contemporary Liberal Arts Teacher-Scholar Kimberly Benston Response 113 Kenneth P. Ruscio iii Liberal Arts Colleges in American Higher Education II. The Present (cont'd) Educational Goals and Student Achievement 121 Built To Engage: Liberal Arts Colleges and 122 Effective Educational Practice George D. Kuh Selective and Non-Selective Alike: An Argument 151 for the Superior Educational Effectiveness of Smaller Liberal Arts Colleges Richard Ekman Response 172 Mitchell J. Chang III. The Future 177 Five Presidents on the Challenges Lying Ahead The Challenges Facing Public Liberal Arts Colleges 178 Mary K. Grant The Importance of Institutional Culture 188 Stephen R. -

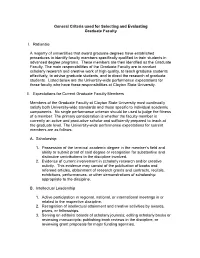

General Criteria Used for Selecting and Evaluating Graduate Faculty I

General Criteria used for Selecting and Evaluating Graduate Faculty I. Rationale A majority of universities that award graduate degrees have established procedures to identify faculty members specifically qualified to train students in advanced degree programs. These members are then identified as the Graduate Faculty. The main responsibilities of the Graduate Faculty are to conduct scholarly research and creative work of high quality, to teach graduate students effectively, to advise graduate students, and to direct the research of graduate students. Listed below are the University-wide performance expectations for those faculty who have these responsibilities at Clayton State University. II. Expectations for Current Graduate Faculty Members Members of the Graduate Faculty at Clayton State University must continually satisfy both University-wide standards and those specific to individual academic components. No single performance criterion should be used to judge the fitness of a member. The primary consideration is whether the faculty member is currently an active and productive scholar and sufficiently prepared to teach at the graduate level. The University-wide performance expectations for current members are as follows: A. Scholarship 1. Possession of the terminal academic degree in the member’s field and ability to submit proof of said degree or recognition for substantive and distinctive contributions to the discipline involved. 2. Evidence of current involvement in scholarly research and/or creative activity. This evidence may consist of the publication of books and refereed articles, obtainment of research grants and contracts, recitals, exhibitions, performances, or other demonstrations of scholarship appropriate to the discipline. B. Intellectual Leadership 1. Active participation in regional, national, or international meetings in or related to the respective discipline. -

The Search for a Vice President for Academic Affairs and Provost • the Evergreen State College 3

The Search for aVice President for Academic Affairs and Provost The Evergreen State College• Olympia, Washington Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................2 Leadership Agenda for the Vice President for Academic Affairs and Provost of The Evergreen State College .........10 About Evergreen ....................................................................3 Academic Visioning for A Progressive, Public College The Evergreen State College ...........................................10 of Liberal Arts and Sciences ................................................3 Academic Excellence Through Commitment to Diversity ....................................................3 Student-Centeredness ......................................................11 Learning Environment .........................................................4 Strengthening Retention Through Student Success ..................................................11 The Five Foci and Six Expectations of an Evergreen Graduate ...................................................4 Enrollment ........................................................................11 The Evergreen Community ....................................................6 Academic Partnership and Campus Community ..........................................................12 Faculty and Staff ..................................................................6 External Relationships .......................................................13 Students ..............................................................................7 -

Pacific Lutheran University Catalog 2016-17 Clarifications As of February 9, 2017 ______Errata Are in Bold And/Or Strikethroughs

Pacific Lutheran University Catalog 2016-17 Clarifications as of February 9, 2017 ________________________________________________________________________________ Errata are in bold and/or strikethroughs ADMISSION UNDERGRADUATE - INTERNATIONAL STUDENTS: http://www.plu.edu/catalog-2016- 2017/undergraduate-admission/international-students/ International Pathway Program to Undergraduate Studies International students who do not meet the English proficiency requirement for undergraduate admission at PLU are encouraged to join the University community through the International Pathway Program. To join the International Pathway Program (IPP), students are required to submit the following: A completed IPP application. School Records: . Documentation of completion of secondary school. For incoming freshmen international students, official secondary school records are required. An official school record (transcript) with English translation from all colleges or universities attended in the United States, home country, or other country. Evidence of English proficiency: . Test of English as a Foreign Language (TOEFL) with a minimum score of 480 (paper test format) 157 (computer-based), 55 (internet-based), or either . International English Language Testing System (IELTS) with a minimum score of 5.0, . Pearson Test of English (PTE) with a minimum score of 42. A completed International Student Declaration of Finances Students have up to twelve months to complete the IPP. Upon completion of the IPP, students will be considered for admission to -

Liberal Arts Education and Information Technology

VIEWPOINT Liberal Arts Education and Information Technology: Time for Another Renewal Liberal arts colleges must accommodate the powerful changes that are taking place in the way people communicate and learn by Todd D. Kelley hree significant societal trends and that institutional planning and deci- Five principal reasons why the future will most certainly have a broad sion making must reflect the realities of success of liberal arts colleges is tied to Timpact on information services rapidly changing information technol- their effective use of information tech- and higher education for some time to ogy. Boards of trustees and senior man- nology are: come: agement must not delay in examining • Liberal arts colleges have an obliga- • the increasing use of information how these changes in society will impact tion to prepare their students for life- technology (IT) for worldwide com- their institutions, both negatively and long learning and for the leadership munications and information cre- positively, and in embracing the idea roles they will assume when they ation, storage, and retrieval; that IT is integral to fulfilling their liberal graduate. • the continuing rapid change in the arts missions in the future. • Liberal arts colleges must demon- development, maturity, and uses of (2) To plan and support technological strate the use of the most significant information technology itself; and change effectively, their colleges must approaches to problem solving and • the growing need in society for have sufficient high-quality information communications to have emerged skilled workers who can understand services staff and must take a flexible and since the invention of the printing and take advantage of the new meth- creative approach to recruiting and press and movable type. -

JENNIFER ROSE WEBSTER [email protected] | Jenniferrosewebster.Com

JENNIFER ROSE WEBSTER [email protected] | jenniferrosewebster.com EDUCATION Ph.D., University of Washington. Department of History March 2015 Dissertation: “Toward a Sacred Topography of Central Asia: Shrines, Pilgrimage, and Gender in Kyrgyzstan,” directed by Professors Glennys Young and Joel Walker M.A.I.S., University of Washington. Jackson School of International Studies, June 2006 Comparative Religion B.A., Reed College. Department of Biology May 2002 Thesis: “Mr. Toad Goes for a Ride: Amphibian Decline, Its Causes, and Solutions through Management and Conservation,” directed by Professor Robert Kaplan FELLOWSHIPS & AWARDS 2012-2013 Roshan Cultural Heritage Institute Graduate Fellowship in Persian Studies 2012 International Research & Exchange Board (IREX) Individual Advanced Research Opportunity Fellowship in Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan 2011 Chester A. Fritz Fellowship for research in Kyrgyzstan 2011 Maurice and Lois Schwartz Fellowship for research in Central Asia 2010 Maurice and Lois Schwartz Fellowship for research in Central Asia 2009 Maurice and Lois Schwartz Fellowship for research in Central Asia 2009-2010 Foreign Language and Area Studies Fellowship, summer and academic year Russian 2008-2009 Foreign Language and Area Studies Fellowship, summer and academic year Persian 2008 INSER Language and Cultural Exposure Travel Award 2005-2006 Foreign Language and Area Studies Fellowship, academic year Uzbek 2004-2005 Foreign Language and Area Studies Fellowship, academic year Arabic 2004 Social Science Research Council Fellowship for Uzbek language study JENNIFER ROSE WEBSTER CV 2 PUBLICATIONS In print: “’My Cousin Bought the Phone for Me. I Never Go to Mobile Shops.’: The Role of Family in Women’s Technological Inclusion in Islamic Culture.” Computer Supported Cooperative Work (2019). -

2014-15 Wacla College Liberal Arts Essay Contest Contacts Institution

2014-15 WaCLA College Liberal Arts Essay Contest Contacts Institution Contact Email Phone Antioch University Seattle Dan Hocoy [email protected] 206-268-4117 Bellevue College W. Russ Payne [email protected] 425-564-2079 Big Bend Community College Central Washington University Laila Abdalla [email protected] 509-963-3533 Roxanne Easley [email protected] 509-963-1877 Centralia College Clatsop Community College Donna Larson [email protected] 503.338.2442 Columbia Basin College Eastern Washington University Lynn Briggs [email protected] 509-359-2328 Edmonds Community College Everett Community College Eugene McAvoy [email protected] 425-388-9031 Heritage University Paula Collucci [email protected] 509-865-0729 ext 3304 Highline College North Seattle Community College Tracy Heinlein [email protected] 206-934-3711 Olympic College Ian Sherman [email protected] 360-475-7658 Saint Martin's University Eric Apfelstadt [email protected] 360-438-4564 Seattle Pacific University Mark Walhout [email protected] 206-281-2981 Seattle University Sven Arvidson [email protected] 206-296-5470 South Puget Sound Community College Debbie Teed [email protected] 360-596-5451 Spokane Falls Community College Glen Cosby [email protected] 509-533-3576 The Evergreen State College Nancy Murray [email protected] 360-867-5497 Trinity Lutheran College David Schulz [email protected] 425-249-4764 University of Puget Sound Sharon Chambers-Gordon [email protected] 253-879-3329 University of Washington - -

The Magisterium of the Faculty of Theology of Paris in the Seventeenth Century

Theological Studies 53 (1992) THE MAGISTERIUM OF THE FACULTY OF THEOLOGY OF PARIS IN THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY JACQUES M. GRES-GAYER Catholic University of America S THEOLOGIANS know well, the term "magisterium" denotes the ex A ercise of teaching authority in the Catholic Church.1 The transfer of this teaching authority from those who had acquired knowledge to those who received power2 was a long, gradual, and complicated pro cess, the history of which has only partially been written. Some sig nificant elements of this history have been overlooked, impairing a full appreciation of one of the most significant semantic shifts in Catholic ecclesiology. One might well ascribe this mutation to the impetus of the Triden tine renewal and the "second Roman centralization" it fostered.3 It would be simplistic, however, to assume that this desire by the hier archy to control better the exposition of doctrine4 was never chal lenged. There were serious resistances that reveal the complexity of the issue, as the case of the Faculty of Theology of Paris during the seventeenth century abundantly shows. 1 F. A. Sullivan, Magisterium (New York: Paulist, 1983) 181-83. 2 Y. Congar, 'Tour une histoire sémantique du terme Magisterium/ Revue des Sci ences philosophiques et théologiques 60 (1976) 85-98; "Bref historique des formes du 'Magistère' et de ses relations avec les docteurs," RSPhTh 60 (1976) 99-112 (also in Droit ancien et structures ecclésiales [London: Variorum Reprints, 1982]; English trans, in Readings in Moral Theology 3: The Magisterium and Morality [New York: Paulist, 1982] 314-31). In Magisterium and Theologians: Historical Perspectives (Chicago Stud ies 17 [1978]), see the remarks of Y. -

OAKWOOD UNIVERSITY Faculty Handbook

FACULTY HANDBOOK OAKWOOD UNIVERSITY Faculty Handbook (Revised 2008) Faculty Handbook Page 1 FACULTY HANDBOOK Table of Contents Section I General Administration Information Oakwood University Mission Statement ........................................................................................... 5 Historic Glimpses .............................................................................................................................. 5 Accreditation ...................................................................................................................................... 5 Affirmative Action and Religious Institution Exemption .................................................................. 6 Sexual Harassment ............................................................................................................................. 6 Drug-free Environment ...................................................................................................................... 7 Establishment and Dissolution of Departments and Majors .............................................................. 8 Section II Policies Governing Faculty Functions Faculty Classifications ...................................................................................................................... 10 Academic Rank ................................................................................................................................. 11 Promotions ....................................................................................................................................... -

42.8% 41.4% 15.8%

The Evergreen State College | New Student Survey 2014 | First‐time, First‐Year Students How many colleges/educational institutions did you apply to? A total of 42.8% of the First‐time, First‐year students who responded to the survey indicated that they applied only to Evergreen. 41.4% applied to 2 to 4 institutions, and 15.8% applied to five or more institutions. How many institutions did you apply to? 100% 75% 50% 42.8% 41.4% 25% 15.8% 0% Just Evergreen 2‐4 Institutions 5 or more How many colleges/educational institutions did you apply to? First‐time, First‐year Students %N Just Evergreen 42.8% 119 2‐4 Institutions 41.4% 115 5 or more 15.8% 44 What were your top three choices of college that you applied to? 42.8% of the First‐time, First‐year Students responding to the survey applied only to Evergreen. Of those students that applied to other institutions (N=159), the majority were baccalaureate universities within the Washington or Oregon. First Second Third Total % of total Choice Choice Choice Mentions The Evergreen State College 220 30 10 260 93.5% Western Washington University 5 18 9 32 11.5% University of Washington 4 4 3 11 4.0% Hampshire College 5 5 10 3.6% Washington State University 6 3 9 3.2% Humboldt State University 1 2 5 8 2.9% Portland State University 3 5 8 2.9% Reed College 2 6 8 2.9% Office of Institutional Research and Assessment December 2014 The Evergreen State College | New Student Survey 2014 | First‐time, First‐Year Students First Second Third Total % of total Choice Choice Choice Mentions Southern Oregon University -

2016-17 Wacla College Liberal Arts Essay Contest Contacts Institution

2016-17 WaCLA College Liberal Arts Essay Contest Contacts Institution Contact Email Phone Antioch University Seattle Dan Hocoy [email protected] 206-268-4117 Bellevue College W. Russ Payne [email protected] 425-564-2079 Big Bend Community College Central Washington University Laila Abdalla [email protected] 509-963-3533 Roxanne Easley [email protected] 509-963-1877 Centralia College Christian Bruhn [email protected] 360-753-3433 ext 258 Clatsop Community College Donna Larson [email protected] 503-338-2442 Columbia Basin College Eastern Washington University Lynn Briggs [email protected] 509-359-2328 Edmonds Community College Everett Community College Eugene McAvoy [email protected] 425-388-9031 Gonzaga University Elisabeth Mermann Jozwiak [email protected] 509-313-5522 Heritage University Paula Collucci [email protected] 509-865-0729 ext 3304 Highline College North Seattle Community College Tracy Heinlein [email protected] 206-934-3711 Olympic College Ian Sherman [email protected] 360-475-7658 Pacific Lutheran University Saint Martin's University Sheila Steiner [email protected] 360-923-8724 Seattle Pacific University Mark Walhout [email protected] 206-281-2981 Seattle University Sven Arvidson [email protected] 206-296-5470 South Puget Sound Community College Debbie Teed [email protected] 360-596-5451 Spokane Falls Community College Glen Cosby [email protected] 509-533-3576 Tacoma Community College The Evergreen State College Nancy Murray [email protected] 360-867-5497 -

Washington State Colleges & Universities

WASHINGTON STATE COLLEGES & UNIVERSITIES • Links to Washington State Colleges & Universities WASHINGTON STATE COLLEGES UNIVERSITIES WEBSITE LINK ANTIOCH UNIVERSITY-SEATTLE . www.antiochseattle.edu BASTYR UNIVERSITY-KENMORE . www.bastyr.edu CENTRAL WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY . www.cwu.edu CITY UNIVERSITY . www.cityu.edu EASTERN WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY . www.ewu.edu EVERGREEN STATE COLLEGE. www.evergreen.edu GONZAGA UNIVERSITY . www.gonzaga.edu PACIFIC LUTHERAN UNIVERSITY. www.plu.edu ST. MARTIN COLLEGE . www.stmartin.edu SEATTLE CENTRAL COLLEGE . www.seattlecentral.edu SEATTLE PACIFIC UNIVERSITY . www.spu.edu SEATTLE UNIVERSITY . www.seattleu.edu UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON . www.washington.edu UNIVERSITY OF PUGET SOUND. www.pugetsound.edu WALLA WALLA UNIVERSITY . www.wallawalla.edu WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY . www.wsu.edu WESTERN GOVERNORS UNIVERSITY . www.wgu.edu WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY-TRI-CITIES . www.tricity.wsu.edu WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY-VANCOUVER . www.vancouver.wsu.edu WESTERN WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY . www.wwu.edu WHITMAN COLLEGE . www.whitman.edu WHITWORTH COLLEGE . www.whitworth.edu COMMUNITY COLLEGES & TECHNICAL SCHOOLS BATES TECHNICAL . www.bates.ctc.edu BELLEVUE COMMUNITY COLLEGE . www.bellevuecollege.edu BELLINGHAM TECHNICAL COLLEGE . www.btc.ctc.edu BIG BEND COMMUNITY COLLEGE . www.bigbend.edu CASCADIA COMMUNITY COLLEGE . www.cascadia.edu CENTRAL SEATTLE COMMUNITY COLLEGE . www.seattlecentral.edu CENTRALIA COMMUNITY COLLEGE . www.centralia.edu CLARK COMMUNITY COLLEGE . www.clark.edu CLOVER PARK TECHNICAL . www.cptc.edu COMMUNITY COLLEGES & TECHNICAL SCHOOLS (cont.) COLUMBIA COLLEGE . www.ccis.edu COLUMBIA BASIN COLLEGE . www.columbiabasin.edu EDMONDS COMMUNITY COLLEGE. www.edcc.edu EVERETT COMMUNITY COLLEGE . www.everettcc.edu GRAYS HARBOR COLLEGE . www.ghc.edu GREEN RIVER COMMUNITY COLLEGE . www.greenriver.edu HIGHLINE COMMUNITY COLLEGE . www.highline.edu LAKE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY .