Development of a Curriculum in the Early American Colleges Author(S): Joe W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Curriculum Vitae Quick Guide

College of Medicine Curriculum Vitae for Promotion and Tenure Quick Guide CV Section AI Screen(s) Feeding to Activity Description and Notes (In Order of Report) This Section . Personal and Contact Name and credentials, primary academic Information CV Header department, division/section, primary administrative . Yearly Data role, office location, and other contact information . Administrative Leadership Postgraduate Education Postgraduate training, including internship, . Postgraduate Education and Training residency, fellowship, and postgraduate research. and Training Education Education leading to formal academic degrees . Education Current and previous professional employment history, including academic, government, Professional hospital/agency, military, and other private/public Experience professional positions . Academic . Administrative Administrative leadership roles such as Dean, . Professional Experience . Government Program Director, Chair, and Chief will also fall . Administrative Leadership . Hospital/Agency under this section, but are to be entered on the . Other Professional Administrative Leadership screen. Committee roles will not appear here. Those roles U.S. Military Experience are to be entered on the Service screens and will fall under Service on the CV report. Honors, awards, and special recognition received Honors and Awards Distinguished professorships and endowed . Honors and Awards positions should be captured here. Specialty certification that is required for professional practice within your discipline . Board Certification, Board Certification Certification received as a result of continuing Practice Certification, and education will not appear here. That should be Licensure entered on the Professional Growth and Development screen. Professional licensure required for professional practice within your discipline . Board Certification, Licensure License numbers will be captured in the system, but Practice Certification, and will not appear on the CV report. -

Pedagogy, Curriculum, Teaching Practices and Teacher Education in Developing Countries

Pedagogy, curriculum, teaching practices and teacher education in developing countries EVIDENCE BRIEF The evidence suggests that when teachers see pedagogy as entailing communication with students they use practices in interactive ways that mean that learning is more likely to take place: the ‘how’ is more important than ‘what’ teachers do. drawing on students’ alignment of professional About this brief backgrounds and experiences. development with teachers’ This paper summaries evidence Six practices used in interactive needs, the promoted pedagogy from a DFID-funded review by ways by effective teachers were and in-class monitoring of Westbrook et al. (2013), entitled more likely to enhance learning: teachers Pedagogy, Curriculum, Teaching support from head teachers demonstration and explanation, Practices and Teacher Education alignment of forms of drawing on subject knowledge in Developing Countries, produced assessment with the school flexible use of whole-class, group by the University of Sussex. The curriculum. review identifies pedagogic and pair work where students practices that most effectively discuss a shared task Practices were disabled by support all students to learn, and frequent, relevant use of learning misalignment of: determines ways that these can be materials beyond the textbook initial teacher training with the supported by teacher education open and closed questioning, school curriculum and the school curriculum. expanding responses, Continuing professional encouraging questioning development with the promoted This brief provides an overview of use of local languages and code pedagogy the strength of evidence, key switching (switching between two the school curriculum with findings and theory of change, to languages within a sentence to assessment. assist policy makers and ensure understanding) Further disabling factors were: researchers in assessing the planning and varying lesson poor communication with the evidence in this field. -

EDUCATION in CHINA a Snapshot This Work Is Published Under the Responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD

EDUCATION IN CHINA A Snapshot This work is published under the responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD. The opinions expressed and arguments employed herein do not necessarily reflect the official views of OECD member countries. This document and any map included herein are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. Photo credits: Cover: © EQRoy / Shutterstock.com; © iStock.com/iPandastudio; © astudio / Shutterstock.com Inside: © iStock.com/iPandastudio; © li jianbing / Shutterstock.com; © tangxn / Shutterstock.com; © chuyuss / Shutterstock.com; © astudio / Shutterstock.com; © Frame China / Shutterstock.com © OECD 2016 You can copy, download or print OECD content for your own use, and you can include excerpts from OECD publications, databases and multimedia products in your own documents, presentations, blogs, websites and teaching materials, provided that suitable acknowledgement of OECD as source and copyright owner is given. All requests for public or commercial use and translation rights should be submitted to [email protected]. Requests for permission to photocopy portions of this material for public or commercial use shall be addressed directly to the Copyright Clearance Center (CCC) at [email protected] or the Centre français d’exploitation du droit de copie (CFC) at [email protected]. Education in China A SNAPSHOT Foreword In 2015, three economies in China participated in the OECD Programme for International Student Assessment, or PISA, for the first time: Beijing, a municipality, Jiangsu, a province on the eastern coast of the country, and Guangdong, a southern coastal province. -

Liberal Arts Colleges in American Higher Education

Liberal Arts Colleges in American Higher Education: Challenges and Opportunities American Council of Learned Societies ACLS OCCASIONAL PAPER, No. 59 In Memory of Christina Elliott Sorum 1944-2005 Copyright © 2005 American Council of Learned Societies Contents Introduction iii Pauline Yu Prologue 1 The Liberal Arts College: Identity, Variety, Destiny Francis Oakley I. The Past 15 The Liberal Arts Mission in Historical Context 15 Balancing Hopes and Limits in the Liberal Arts College 16 Helen Lefkowitz Horowitz The Problem of Mission: A Brief Survey of the Changing 26 Mission of the Liberal Arts Christina Elliott Sorum Response 40 Stephen Fix II. The Present 47 Economic Pressures 49 The Economic Challenges of Liberal Arts Colleges 50 Lucie Lapovsky Discounts and Spending at the Leading Liberal Arts Colleges 70 Roger T. Kaufman Response 80 Michael S. McPherson Teaching, Research, and Professional Life 87 Scholars and Teachers Revisited: In Continued Defense 88 of College Faculty Who Publish Robert A. McCaughey Beyond the Circle: Challenges and Opportunities 98 for the Contemporary Liberal Arts Teacher-Scholar Kimberly Benston Response 113 Kenneth P. Ruscio iii Liberal Arts Colleges in American Higher Education II. The Present (cont'd) Educational Goals and Student Achievement 121 Built To Engage: Liberal Arts Colleges and 122 Effective Educational Practice George D. Kuh Selective and Non-Selective Alike: An Argument 151 for the Superior Educational Effectiveness of Smaller Liberal Arts Colleges Richard Ekman Response 172 Mitchell J. Chang III. The Future 177 Five Presidents on the Challenges Lying Ahead The Challenges Facing Public Liberal Arts Colleges 178 Mary K. Grant The Importance of Institutional Culture 188 Stephen R. -

The Neighborhood School Curriculum Outline

The Neighborhood School Curriculum Outline 2008-2009 Curriculum is at the heart of our school. It is born of the interests and developmental capacity of the children and the goals and knowledge of the teachers. We understand that children are learning to make sense of the world. They need to be equipped to live in the world. We work with each child to further that child’s academic and social development. The curriculum provides opportunities for children to find new areas of interest and strength as they grow, to present their ideas and be well spoken and self assured in public presentations. Children develop a sense of responsibility towards the community through their group work, as well as towards their own individual learning. We provide children with work that is real. We look at what real writers do, what good readers to in order to build curriculum that is important and relevant to the lives of the children. We teach children to be researchers from pre- kindergarten up through 5th grade and to reflect on their experiences to ask questions and learn. We assess children through looking at collections of their work, through observing them work and participate in class activities, by keeping notes on their progress and through conferencing with them about their work. Every spring, each grade level and the administration meet to decide the curriculum for the following year. Our mixed age classes are on a two year cycle of curriculum, to match the two years the children are in the classes. We choose topics and areas of study that are important and worthwhile, that spark the ideas of children, that provide a platform for later learning. -

The Church Militant: the American Loyalist Clergy and the Making of the British Counterrevolution, 1701-92

The Church Militant: The American Loyalist Clergy and the Making of the British Counterrevolution, 1701-92 Peter W. Walker Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2016 © 2016 Peter Walker All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Church Militant: The American Loyalist Clergy and the Making of the British Counterrevolution, 1701-92 Peter W. Walker This dissertation is a study of the loyalist Church of England clergy in the American Revolution. By reconstructing the experience and identity of this largely-misunderstood group, it sheds light on the relationship between church and empire, the role of religious pluralism and toleration in the American Revolution, the dynamics of loyalist politics, and the religious impact of the American Revolution on Britain. It is based primarily on the loyalist clergy’s own correspondence and writings, the records of the American Loyalist Claims Commission, and the archives of the SPG (the Church of England’s missionary arm). The study focuses on the New England and Mid-Atlantic colonies, where Anglicans formed a religious minority and where their clergy were overwhelmingly loyalist. It begins with the founding of the SPG in 1701 and its first forays into America. It then examines the state of religious pluralism and toleration in New England, the polarising contest over the proposed creation of an American bishop after the Seven Years’ War, and the role of the loyalist clergy in the Revolutionary War itself, focusing particularly on conflicts occasioned by the Anglican liturgy and Book of Common Prayer. -

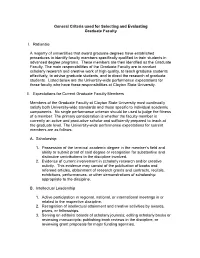

General Criteria Used for Selecting and Evaluating Graduate Faculty I

General Criteria used for Selecting and Evaluating Graduate Faculty I. Rationale A majority of universities that award graduate degrees have established procedures to identify faculty members specifically qualified to train students in advanced degree programs. These members are then identified as the Graduate Faculty. The main responsibilities of the Graduate Faculty are to conduct scholarly research and creative work of high quality, to teach graduate students effectively, to advise graduate students, and to direct the research of graduate students. Listed below are the University-wide performance expectations for those faculty who have these responsibilities at Clayton State University. II. Expectations for Current Graduate Faculty Members Members of the Graduate Faculty at Clayton State University must continually satisfy both University-wide standards and those specific to individual academic components. No single performance criterion should be used to judge the fitness of a member. The primary consideration is whether the faculty member is currently an active and productive scholar and sufficiently prepared to teach at the graduate level. The University-wide performance expectations for current members are as follows: A. Scholarship 1. Possession of the terminal academic degree in the member’s field and ability to submit proof of said degree or recognition for substantive and distinctive contributions to the discipline involved. 2. Evidence of current involvement in scholarly research and/or creative activity. This evidence may consist of the publication of books and refereed articles, obtainment of research grants and contracts, recitals, exhibitions, performances, or other demonstrations of scholarship appropriate to the discipline. B. Intellectual Leadership 1. Active participation in regional, national, or international meetings in or related to the respective discipline. -

Chapter 4: Putting It Into Practice: Curriculum and Pedagogy

3XWWLQJLWLQWRSUDFWLFH 4 &XUULFXOXPDQGSHGDJRJ\ 4.1 Curriculum, from the Latin for ‘course’, is the content or subject matter that is taught. Pedagogy, from the Greek words for ‘boy’ and ‘guide’, refers to the art or science of teaching or the techniques used to teach students. The notion of a teacher guiding students through a course of study has more contemporary relevance than the content driven, ‘drill and skill’, approaches that characterised schooling until the last few decades of the 1900s. 4.2 Good teachers have always, through sound and supportive teacher/student relationships, guided students through what they need and want to learn. This chapter considers the importance of relevant curricula and engaging pedagogy in promoting learning as well as the methods used to assess student achievement. Curriculum and pedagogy 4.3 If the definitions of curriculum and pedagogy are clear, the separation of the two in classrooms is not. While the curriculum is the content that education departments mandate must be taught, classroom teachers have significant responsibility for, and control over, how the curriculum is presented and delivered. In practice, an inspired and talented teacher can energise dull content and find ways to link it to real life while a mediocre or unmotivated teacher can compromise the appeal of the most relevant and imaginative curriculum by poor delivery. 4.4 The research at Flinders University by Slade and Trent indicates that boys are aware of and reactive to what they view to be irrelevant curriculum and poor teaching. Boys see curriculum and pedagogy as inseparable from each other and from other aspects of schooling. -

Liberal Arts Education and Information Technology

VIEWPOINT Liberal Arts Education and Information Technology: Time for Another Renewal Liberal arts colleges must accommodate the powerful changes that are taking place in the way people communicate and learn by Todd D. Kelley hree significant societal trends and that institutional planning and deci- Five principal reasons why the future will most certainly have a broad sion making must reflect the realities of success of liberal arts colleges is tied to Timpact on information services rapidly changing information technol- their effective use of information tech- and higher education for some time to ogy. Boards of trustees and senior man- nology are: come: agement must not delay in examining • Liberal arts colleges have an obliga- • the increasing use of information how these changes in society will impact tion to prepare their students for life- technology (IT) for worldwide com- their institutions, both negatively and long learning and for the leadership munications and information cre- positively, and in embracing the idea roles they will assume when they ation, storage, and retrieval; that IT is integral to fulfilling their liberal graduate. • the continuing rapid change in the arts missions in the future. • Liberal arts colleges must demon- development, maturity, and uses of (2) To plan and support technological strate the use of the most significant information technology itself; and change effectively, their colleges must approaches to problem solving and • the growing need in society for have sufficient high-quality information communications to have emerged skilled workers who can understand services staff and must take a flexible and since the invention of the printing and take advantage of the new meth- creative approach to recruiting and press and movable type. -

The Magisterium of the Faculty of Theology of Paris in the Seventeenth Century

Theological Studies 53 (1992) THE MAGISTERIUM OF THE FACULTY OF THEOLOGY OF PARIS IN THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY JACQUES M. GRES-GAYER Catholic University of America S THEOLOGIANS know well, the term "magisterium" denotes the ex A ercise of teaching authority in the Catholic Church.1 The transfer of this teaching authority from those who had acquired knowledge to those who received power2 was a long, gradual, and complicated pro cess, the history of which has only partially been written. Some sig nificant elements of this history have been overlooked, impairing a full appreciation of one of the most significant semantic shifts in Catholic ecclesiology. One might well ascribe this mutation to the impetus of the Triden tine renewal and the "second Roman centralization" it fostered.3 It would be simplistic, however, to assume that this desire by the hier archy to control better the exposition of doctrine4 was never chal lenged. There were serious resistances that reveal the complexity of the issue, as the case of the Faculty of Theology of Paris during the seventeenth century abundantly shows. 1 F. A. Sullivan, Magisterium (New York: Paulist, 1983) 181-83. 2 Y. Congar, 'Tour une histoire sémantique du terme Magisterium/ Revue des Sci ences philosophiques et théologiques 60 (1976) 85-98; "Bref historique des formes du 'Magistère' et de ses relations avec les docteurs," RSPhTh 60 (1976) 99-112 (also in Droit ancien et structures ecclésiales [London: Variorum Reprints, 1982]; English trans, in Readings in Moral Theology 3: The Magisterium and Morality [New York: Paulist, 1982] 314-31). In Magisterium and Theologians: Historical Perspectives (Chicago Stud ies 17 [1978]), see the remarks of Y. -

OAKWOOD UNIVERSITY Faculty Handbook

FACULTY HANDBOOK OAKWOOD UNIVERSITY Faculty Handbook (Revised 2008) Faculty Handbook Page 1 FACULTY HANDBOOK Table of Contents Section I General Administration Information Oakwood University Mission Statement ........................................................................................... 5 Historic Glimpses .............................................................................................................................. 5 Accreditation ...................................................................................................................................... 5 Affirmative Action and Religious Institution Exemption .................................................................. 6 Sexual Harassment ............................................................................................................................. 6 Drug-free Environment ...................................................................................................................... 7 Establishment and Dissolution of Departments and Majors .............................................................. 8 Section II Policies Governing Faculty Functions Faculty Classifications ...................................................................................................................... 10 Academic Rank ................................................................................................................................. 11 Promotions ....................................................................................................................................... -

Middle School Curriculum Guide 2017-2018

MIDDLE SCHOOL CURRICULUM GUIDE 2017-2018 As a member of the Princeton Day School community, I will pursue excellence in scholarship and character. I will try to be trustworthy, kind, honest, and fair; give my best in and out of the classroom and on the playing field; be respectful of myself, of property, and of all members of our community; take responsibility for my actions; maintain a sense of humor. Welcome to the Middle School at Princeton Day School, a lively and engaging place for students in grades 5 through 8. Our goal is to create a culture where students feel safe, valued, celebrated and known. The quote above is on a plaque in the Middle School, and it truly captures what we strive for here at Princeton Day School. In the Middle School at PDS, we encourage our students to be involved in activities both in and out of the classroom. We encourage them to take risks and value their own voice in the classroom. We believe in giving students opportunities to make mistakes, and then learn from them in a caring and supportive environment. In addition, we place great emphasis on keeping a growth mindset. We want students to view effort as the key to success; to keep focused on continued—life-long—growth; and to keep trying even though they may experience setbacks. Class sizes are kept small, and teachers, students, and parents work very closely together. Dedicated and talented faculty foster clear, thoughtful communication between home and school, forming a partnership that values educational excellence. At Princeton Day School, we teach skills and knowledge, but also, more critically, we teach our students how to think and learn.