John Vardill: a Loyalist's Progress

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table of Contents

T a b l e C o n T e n T s I s s u e 9 s u mm e r 2 0 1 3 o f pg 4 pg 18 pg 26 pg 43 Featured articles Pg 4 abraham lincoln and Freedom of the Press A Reappraisal by Harold Holzer Pg 18 interbranch tangling Separating Our Constitutional Powers by Judith s. Kaye Pg 26 rutgers v. Waddington Alexander Hamilton and the Birth Pangs of Judicial Review by David a. Weinstein Pg 43 People v. sanger and the Birth of Family Planning clinics in america by Maria T. Vullo dePartments Pg 2 From the executive director Pg 58 the david a. Garfinkel essay contest Pg 59 a look Back...and Forward Pg 66 society Officers and trustees Pg 66 society membership Pg 70 Become a member Back inside cover Hon. theodore t. Jones, Jr. In Memoriam Judicial Notice l 1 From the executive director udicial Notice is moving forward! We have a newly expanded board of editors Dearwho volunteer Members their time to solicit and review submissions, work with authors, and develop topics of legal history to explore. The board of editors is composed J of Henry M. Greenberg, Editor-in-Chief, John D. Gordan, III, albert M. rosenblatt, and David a. Weinstein. We are also fortunate to have David l. Goodwin, Assistant Editor, who edits the articles and footnotes with great care and knowledge. our own Michael W. benowitz, my able assistant, coordinates the layout and, most importantly, searches far and wide to find interesting and often little-known images that greatly compliment and enhance the articles. -

The Church Militant: the American Loyalist Clergy and the Making of the British Counterrevolution, 1701-92

The Church Militant: The American Loyalist Clergy and the Making of the British Counterrevolution, 1701-92 Peter W. Walker Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2016 © 2016 Peter Walker All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Church Militant: The American Loyalist Clergy and the Making of the British Counterrevolution, 1701-92 Peter W. Walker This dissertation is a study of the loyalist Church of England clergy in the American Revolution. By reconstructing the experience and identity of this largely-misunderstood group, it sheds light on the relationship between church and empire, the role of religious pluralism and toleration in the American Revolution, the dynamics of loyalist politics, and the religious impact of the American Revolution on Britain. It is based primarily on the loyalist clergy’s own correspondence and writings, the records of the American Loyalist Claims Commission, and the archives of the SPG (the Church of England’s missionary arm). The study focuses on the New England and Mid-Atlantic colonies, where Anglicans formed a religious minority and where their clergy were overwhelmingly loyalist. It begins with the founding of the SPG in 1701 and its first forays into America. It then examines the state of religious pluralism and toleration in New England, the polarising contest over the proposed creation of an American bishop after the Seven Years’ War, and the role of the loyalist clergy in the Revolutionary War itself, focusing particularly on conflicts occasioned by the Anglican liturgy and Book of Common Prayer. -

Download Searchable

/& A^ S^^lS^, /.cr^S^^^^/iil &i^ ^ * * -^ iy^^nrfc*< //^*^^ c^^^^-^^*-^... ^ A^ __^ 1 ^i-^J THE BLACK BOOK PAGE 15 OF ORIGINAL MANUSCRIPT IN HANDWRITING OF MYLES COOPER The BLACK BOOK, or BOOK OF MIS DEMEANORS in KING'S COLLEGE, New-York, ijji-i-jjz,. Now published for the first Time. New-York: Printed for COLUMBIANA atthe UNIVERSITYPRESS, M.CM.XXXI. Edited and annotated by MILTON HALSEY THOMAS, B.Sc. Curator of Columbiana Reprinted from the COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY QUARTERLY March, 1931, Vol. XXIII, No. i FOREWORD Columbia is most fortunate in having had preserved through a hundred and sixty years that extraordinary docu ment, "The Book of Misdemeanours in King's College, New York." Myles Cooper, coming to the College after seven years at Oxford, did much to fit it into the pattern of his alma mater, and as part of his system of rigid discipline he introduced the Black Book, which had been for centuries a tradition at Queen's College, Oxford. In its pages, as in no other record which has come down to us, we can be with the students of King's College day by day in the most inti mate manner. Aside from its interest as a human docu ment, the Black Book has great value as an unconsciously transmitted source-book with its off-hand mention of facts which historians will eagerly pounce upon. The original is a black leather volume measuring seven and three-fourths by six and one-fourth inches; it is a blank- book of about a hundred and fifty leaves, of which only the first thirty-one pages and the last page bear writing. -

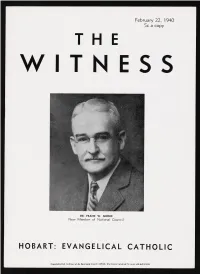

The W I T N E

February 22, 1940 5c a copy THE WITNESS DR. FRANK W. MOORE New Member of National Council HOBART: EVANGELICAL CATHOLIC Copyright 2020. Archives of the Episcopal Church / DFMS. Permission required for reuse and publication. SCHOOLS CLERGY NOTES SCHOOLS BARROWS, W. S., retired headmaster of De- Veaux School, Niagara Falls, N. Y., died at tElfg dînerai ©ijcologtcal the age of 79 on Jan. 27th in Lexington, Va. K e m p e r 1T O X ^em in arg BARTH, T. N., rector of St. Bartholomew’s p Church, Baltimore, Md., has accepted a call KENOSHA, WISCONSIN Three-year undergraduate to Calvary Church, Memphis, Tenn., and course of prescribed and elective will take over the duties in March. Episcopal Boarding and Day School. DUNSTAN, A. M., rector of St. Thomas Preparatory to all colleges. Unusual study. Church, Dover, N. H., since 1927, resigned his position on February 1st. opportunities in Art and Music. Fourth-year course for gradu FORTUNE, Ft V. D., formerly assistant Complete sports program. Junior ates, offering larger opportunity minister at St. Paul’s Church, Cleveland School. Accredited. Address: for specialization. Heights, Ohio, was instituted as rector of St. Paul’s Church, Steubenville, Ohio, on SISTERS OF ST. MARY Provision for more advanced January 25th by Bishop Beverley D. Tucker. work, leading to degrees of S.T.M. HATHEWAY, C. H., former canon of the Box W. T. and B.Th. Cathedral of All Saints, Albany, New York, Kemper Hall Kenosha, Wisconsin died at his home in Hudson on February ADDRESS 12th. He was 80 years of age. -

Development of a Curriculum in the Early American Colleges Author(S): Joe W

The Development of a Curriculum in the Early American Colleges Author(s): Joe W. Kraus Source: History of Education Quarterly, Vol. 1, No. 2, (Jun., 1961), pp. 64-76 Published by: History of Education Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/367641 Accessed: 02/05/2008 14:31 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=hes. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We enable the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org THE DEVELOPMENT OF A CURRICULUM IN THE EARLY AMERICAN COLLEGES Joe W. Kraus The early American colleges were smaller and poorer counter- parts of the universities of Great Britain, rather than indigenous institutions, and the mother country was the source of their cur- riculum. -

Britain's Conciliatory Proposal of 1776, a Study in Futility John Taylor Savage Jr

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Master's Theses Student Research 6-1968 Britain's conciliatory proposal of 1776, A study in futility John Taylor Savage Jr. Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/masters-theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Savage, John Taylor Jr., "Britain's conciliatory proposal of 1776, A study in futility" (1968). Master's Theses. Paper 896. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Project Name: S °''V°'~C,._ ~JoV1.-.._ \ _ I " ' J Date: Patron: Specialist: Oc,~ o7, Co.-. .... or ZD•S ~Tr ""0. ""I Project Description: Hardware Specs: BRITAIN'S CONCILIATORY PROPOSAL OF 1778, A STUDY IN FUTILITY BY JOHN TAYLOR SAVAGE, JR. A THESIS SUBMITI'ED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF RICHMOND IN CANDIDACY FOR IBE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN HISTORY JUNE, 1968 L:·--:..,:.·:·· -. • ~ ' > ... UNJVE:i1'.':~ i ., ·:.·. ',' ... - \ ;, '.. > TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE PREFACE • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • iv INTRODUCTION • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • v CHAPTER I. THE DECEMBER TO FEBRUARY PREPARATIONS LEADING TO THE NORTH CONCILIATORY PLAN OF 1778 • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 1 II. CONCILIATORY PROPOSAL AND COMMISSIONERS: FEBRUARY TO APRIL 1778 • • • • • • • • • • 21 III. THE RESPONSE IN ENGLAND AND FRANCE, FROM MARCH TO MAY, TO BRITAIN'S CONCILIATORY EFFORTS • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 52 IV. AMERICA PREPARES FOR THE RECEPTION OF THE CARLISLE Cu'1MISSION, MARCH TO JUNE 1778. • 70 V. THE JUNE NEGOTIATIONS • • • • • • • • • • • 92 VI. THE SUMMER NEGOTIATIONS: A DISAPPOINT· MENT •••••••• • • • • • • • • • • • 115 VII. -

New York Genealogical and Biographical Record, Vol 18

m<[ o V ^*^°x. „.-.*- ^.•^"•/ *^^'.?^\/ %*^-\*° .*' -'Mi' \/ •«• %/ -^"t *--^/ • ^ o5^^ ^x>^ ' "i'^ ^'} ei» * ^>syS->" • <L^ .-^'' r> * <? . * C (I o V ,0^ •^'^.-J^ .. V Digitized by the Internet Arciiive in 2008 with funding from The Library of Congress http://www.archive.org/details/newyorkgenealog18newy .^^ THE NEW YORK GENEA^ii*li^ND Biographical -^7 DEVOTED TO THE INTERESTS OF AMERICAN GENEALOGY AND BIOGRAPHY. ISSUED QUARTERLY. VOLUME XVIII., 1887. 1WASHIN6V PUBLISHED BY THE SOCIETY MoTT Memorial Hall, No. 64 Madison Avenue, NEW YORK CITY. PUBLICATION COMMITTEE: Rev. BEVERLEY R. BETTS, Chairman. Dr. SAMUEL S, PURPLE. Gen. JAS. GRANT WILSON, ex-officio. Mr. CHARLES B. MOORE. 4122 Press of J. J. Little & Co. , Astor Place, New York. / ) . J:m}7/zrpif\ IE IRDSKT I^E^. SARfflOJEL !p[a©^®®STjl FIRST 3ISEOP OF SEW-YOSK. Original Portrait in. dve aosaessiou of DT Jain es R.Chi1toii THE NEW YORK Vol. XVIII. NEW YORK, JANUARY, 1887. No. i. SAMUEL PROVOOST, FIRST BISHOP OF NEW YORK.* AN ADDRESS TO THE GENEALOGICAL AND BIOGRAPHICAL SOCIETY. By Gen. Ja.s. Grant Wilson. [With a Portrait of BishoJ> Provoost.) Mr. Chairman, Ladies and Gentlemen : " It is a pleasing fancy which the elder Disraeli has preserved, somewhere, in amber, that portrait-painting had its origin in the inventive fondness of a girl, who traced upon the wall the iirofile of her sleeping lover. It was an outline merely, but love could always fill it up and make it live. It is the most that I can hope to do for my dear, dead brother. But how many there are—the world-wide circle of his friends, his admiring diocese, his attached clergy, the immediate inmates of his heart, the loved ones of his hearth—from whose informing breath it will take life, reality, and beauty." These beautiful words are borrowed from Bishop Doane, of New Jersey, who used them as an introductory paragraph in a memorial of one of Bishop Pro- voost's successors, Jonathan Mayhew Wainwright. -

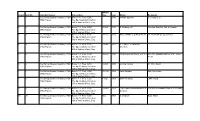

Count Item No. Calendar Header Subsection Month/ Day Year Writer Recipient 1 1 the Bishop Samuel Seabury (1729- 1796) Papers

Month/ Count Item No. Calendar Header Subsection Day Year Writer Recipient 1 1 The Bishop Samuel Seabury (1729- Boxes 1-3, Files 1-250 1740 William Spencer S. Seabury, Sr. 1796) Papers The Bp. Seabury Collection Gift of Andrew Oliver, Esq. 2 2 The Bishop Samuel Seabury (1729- Boxes 1-3, Files 1-250 23-Oct 1753 S. Seabury, Sr. Thomas Sherlock, Bp. of London 1796) Papers The Bp. Seabury Collection Gift of Andrew Oliver, Esq. 3 3 The Bishop Samuel Seabury (1729- Boxes 1-3, Files 1-250 24-Dec 1755 Moses Mathers & Noah Wells Dr. Bearcroft (Sec'y, S.P.G.) 1796) Papers The Bp. Seabury Collection Gift of Andrew Oliver, Esq. 4 4 The Bishop Samuel Seabury (1729- Boxes 1-3, Files 1-250 23-Jan 1757 S. Clowes, Jr. and Wm. 1796) Papers The Bp. Seabury Collection Sherlock Gift of Andrew Oliver, Esq. 5 5 The Bishop Samuel Seabury (1729- Boxes 1-3, Files 1-250 28-Feb 1757 Philip Bearcroft (Sec'y, S.P.G.) Rev. Mr. Obadiah Mather & Mr. Noah 1796) Papers The Bp. Seabury Collection Wells Gift of Andrew Oliver, Esq. 6 6 The Bishop Samuel Seabury (1729- Boxes 1-3, Files 1-250 30-Oct 1760 Archbp. Secker Dr. Wm. Smith 1796) Papers The Bp. Seabury Collection Gift of Andrew Oliver, Esq. 7 7 The Bishop Samuel Seabury (1729- Boxes 1-3, Files 1-250 16-Feb 1762 Jane Durham Mrs. Ann Hicks 1796) Papers The Bp. Seabury Collection Gift of Andrew Oliver, Esq. 8 8 The Bishop Samuel Seabury (1729- Boxes 1-3, Files 1-250 4-Sep 1763 Sam'l Seabury John Troup 1796) Papers The Bp. -

Toleration and Reform: Virginia's Anglican Clergy, 1770-1776

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2009 Toleration and Reform: Virginia's Anglican Clergy, 1770-1776 Stephen M. Volpe College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the History of Religion Commons, Other Religion Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Volpe, Stephen M., "Toleration and Reform: Virginia's Anglican Clergy, 1770-1776" (2009). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626590. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-4yj8-rx68 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Toleration and Reform: Virginia’s Anglican Clergy, 1770-1776 Stephen M. Volpe Pensacola, Florida Bachelor of Arts, University of West Florida, 2004 A Thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of History The College of William and Mary August, 2009 APPROVAL PAGE This Thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts t / r ^ a — Stephen M. Volpe Approved by the Committee, July, 2009 Committee Chair Dr. Christopher Grasso, Associate Professor of History Lyon Gardiner Tyler Department of History The College of William and Mary ___________H h r f M ________________________ Dr. Jam es Axtell, Professor Emeritus of History Lyon Gardiner Tyler Department of History The College of William and Mary X ^ —_________ Dr. -

THE HISTORICAL SOCIETY of PENNSYLVANIA President, Boies Penrose Honorary Price-President', Roy F

THE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF PENNSYLVANIA President, Boies Penrose Honorary Price-President', Roy F. Nichols Vice-Presidents Richmond P. Miller Harold D. Saylor Ernest C. Savage Thomas E. Wynne Secretary\ Howard H. Lewis Treasurer^ George E. Nehrbas Councilors Benjamin Chew Robert L. McNeil, Jr. Mrs. L. M. C. Smith Thomas C. Cochran Henry J. Magaziner Martin P. Snyder H. Richard Dietrich, Jr. Bertram L. O'Neill Frederick B. Tolles Mrs. Anthony N. B. Garvan Henry R. Pemberton David Van Pelt Joseph W. Lippincott, Jr. E. P. Richardson H. Justice Williams Caroline Robbins Counsel, R. Sturgis Ingersoll I Director^ Nicholas B. Wainwright e$> cp <£ cjj Founded in 1824, The Historical Society of Pennsylvania has long been a center of research in Pennsylvania and American history. It has accumulated an important historical collection, chiefly through contributions of family, political, and business manuscripts, as well as letters, diaries, newspapers, magazines, maps, prints, paintings, photographs, and rare books. Additional contributions of such a nature are urgently solicited for preservation in the Society's fireproof building where they may be consulted by scholars. Membership, There are various classes of membership: general, $ 15.00; associate, $25.00; patron, $100.00; life, $300.00; benefactor, $1,000. Members receive certain privileges in the use of books, are invited to the Society's historical addresses and receptions, and receive The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. Those interested in joining the Society are invited to submit their names. Hours: The Society is open to the public Monday, 1 P.M. to 9 P.M.; Tuesday through Friday, 9 A.M. -

The Colonial Clergy of the Middle Colonies New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania 1628-1776

The Colonial Clergy of the Middle Colonies New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania 1628-1776 BY FREDERICK LEWIS WEIS EDITOR'S NOTE NE of the most useful tools in the chest of the bibliog- O rapher, historian, and librarian is the series of little volumes by Dr. Weis on the colonial clergy. The gap in this series, the volume on the clergy of the Middle Colonies, was proving such a great hindrance to our revision of Evans' American Bibliography, that we have decided to print this volume for our own use, and to publish it in order to share it with others. The first volume of this series. The Colonial Clergy and the Colonial Churches of New England (Lancaster, 1936), is out of print. The Colonial Clergy of Maryland, Delaware, and Georgia (Lancaster, 1950), and The Colonial Clergy of Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina (Boston, 1955) may be obtained of the author (at Dublin, New Hampshire) for $3 a volume. The institutional data which is provided at the end of the New England volume is for the other colonies issued in a separate volume. The Colonial Churches and the Colonial Clergy in the Middle and Southern Colonies (Lancaster, 1938), which is still available from the author. The biographical data on the clergy of the Middle Colonies here printed is also available in monograph form from the American Antiquarian Society. C. K. S. i68 AMERICAN ANTIQUARIAN SOCIETY [Oct., BENJAMIN ABBOTT, b. Long Island, N.Y., 1732; member of the Philadelphia Conference of Methodists, 1773-1789; preached at Penns- neck, N. -

The Living Church· Iune 4

THE PARISH ADMINISTRATION/TRIENNIAL ISSUE [IVING CHURCH AN INDEPENDENT WEEKLY SERVING EPISCOPALIANS• JUNE 4, 2006 • $2.50 300 Years of Chang·ng Fortunes WHY DO "IN-THE-KNOW " EPISCOPALIANS CHOOSE WESTMINSTER COMMUNITIE S OF FLORIDA? They know about the unequalled Convenience Location Amenities Dining choices Housekeeping service Property and appliance maintenance Security Estate planning options Continuum of care Active lifestyle C oME AND STAY TH REE DAYS AND TWO ATTENTION Episcopal priests, missionaries, Christian NI GHTS ON US ! * educators, their spouses or surviving spouses. You may be eligible for a 10 10 entnnce f P n at our Bradenton, Experience urban excitement, St. Petersburg, and Jacksonville communities through our waterfront elegance , or Honorable Service Grant Program. Call coordinator, wooded serenity at a Donna Smaage, today at (800) 948-1881. Westminster community and let us impress you with our Westminster Communities of Florida signature Legendary Service' M. www.WestminsterRetirement.com • TransportJtlon ,snot included. (800) 948- 1881 ' Bradenton I Ft. Lauderdale I Ft. Walton Beach IJacksonville Orlando I Pensacola I Sr. Petersburg I Tallahassee I Winter Park Comefor the Lifestyle.Stay for a Lifetimer" The objective of THELIVING CHURCHmagazine is to build up the body of Christ, by describing how God is moving in his Church; by reporting news of the Church in an unbiased manner; and by presenting diverse points of view. THIS WEEK ---------- NEWS 21 Sensitive Issues to be Addressed Early at General Convention FEATURES 15 Faith in Daily Life Anne Rowthom BYPETER EATON 18 ECW Offers Change of Pace During General Convention Beth Marqurut (center left) and others 26 with Spokes for F'olks.