Rolling Thunder Post-Mortem

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View Book Sample

DANGEROUS GAMES: HOW TO PLAY (BOOK #1) BY MATT FORBECK ALSO BY MATT FORBECK Hard Times in Dragon City (Shotguns & Sorcery #1) Bad Times in Dragon City (Shotguns & Sorcery #2) End Times in Dragon City (Shotguns & Sorcery #3) Leverage: The Con Job Matt Forbeck’s Brave New World: Revolution Matt Forbeck’s Brave New World: Revelation Matt Forbeck’s Brave New World: Resolution Amortals Vegas Knights Carpathia Magic: The Gathering comics Guild Wars: Ghosts of Ascalon (with Jeff Grubb) Mutant Chronicles Star Wars vs. Star Trek Secret of the Spiritkeeper Prophecy of the Dragons The Dragons Revealed Blood Bowl Blood Bowl: Dead Ball Blood Bowl: Death Match Blood Bowl: Rumble in the Jungle Eberron: Marked for Death Eberron: The Road to Death Eberron: The Queen of Death Full Moon Enterprises Beloit, WI, USA www.forbeck.com Dangerous Games and all prominent fictional characters, locations, and organizations depicted herein are trademarks of Matt Forbeck. The appearance of other trademarks herein is not intended as a challenge to those trademarks. © 2013 by Matt Forbeck. All Rights Reserved. 12 for ’12 logo created by Jim Pinto. Dangerous Games logo created by Matt Forbeck. Cover design by Matt Forbeck. This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Dedicated to my wife Ann and our kids Marty, Pat, Nick, Ken, and Helen. They’re always my favorite players. Thanks to Peter Adkison, Adrian Swartout, Owen Seyler, and the rest of the Gen Con staff for being such great sports and even better friends. -

E6: the Game Inside the World's Most Popular Roleplaying Game

E6 The Game Inside the World’s Most Popular Roleplaying Game v 0.4.1 BY RYAN STOUGHTON E6: The Game Inside the World’s Most Popular Roleplaying Game E6: The Game Inside the World’s Most Popular Roleplaying Game CREDITS WRITING: Ryan Stoughton LAYOUT: J.A. Dettman The original EN World thread from which DESIGNATION OF OPEN CONTENT this document was transcribed is available All text in this document is declared Open at the following URL: Content, as per Section 15 of the Open Gaming License. http://www.enworld.org/ showthread.php?t=200754 2 3 E6: The Game Inside the World’s Most Popular Roleplaying Game E6: The Game Inside the World’s Most Popular Roleplaying Game INTRODUCTION WHAT IS E6? In E6, the stats of an average person are Earlier this year Ryan Dancey suggested the stats of a 1st-level commoner. Like that d20 has four distinct quartiles of play: their medieval counterparts, this person has never travelled more than a mile from Levels 1-5: Gritty fantasy their home. Imagine a 6th-level Wizard Levels 6-10: Heroic fantasy or 6th-level Fighter from the commoner’s Levels 11-15: Wuxia perspective. The wizard could kill Levels 16-20: Superheroes everyone in your village with a few words. The fighter could duel with ten armed There’s been some great discussion about guards in a row and kill every one of them. how to define those quartiles, and how If you spot a manticore, everyone you each different quartile suited some groups know is in terrible, terrible danger. -

Monster Manual

CREDITS MONSTER MANUAL DESIGN MONSTER MANUAL REVISION Skip Williams Rich Baker, Skip Williams MONSTER MANUAL D&D REVISION TEAM D&D DESIGN TEAM Rich Baker, Andy Collins, David Noonan, Monte Cook, Jonathan Tweet, Rich Redman, Skip Williams Skip Williams ADDITIONAL DEVELOPMENT ADDITIONAL DESIGN David Eckelberry, Jennifer Clarke Peter Adkison, Richard Baker, Jason Carl, Wilkes, Gwendolyn F.M. Kestrel, William W. Connors, Sean K Reynolds Bill Slavicsek EDITORS PROOFREADER Jennifer Clarke Wilkes, Jon Pickens Penny Williams EDITORIAL ASSITANCE Julia Martin, Jeff Quick, Rob Heinsoo, MANAGING EDITOR David Noonan, Penny Williams Kim Mohan MANAGING EDITOR D&D CREATIVE DIRECTOR Kim Mohan Ed Stark CORE D&D CREATIVE DIRECTOR DIRECTOR OF RPG R&D Ed Stark Bill Slavicsek DIRECTOR OF RPG R&D ART DIRECTOR Bill Slavicsek Dawn Murin VISUAL CREATIVE DIRECTOR COVER ART Jon Schindehette Henry Higginbotham ART DIRECTOR INTERIOR ARTISTS Dawn Murin Glen Angus, Carlo Arellano, Daren D&D CONCEPTUAL ARTISTS Bader, Tom Baxa, Carl Critchlow, Brian Todd Lockwood, Sam Wood Despain, Tony Diterlizzi, Scott Fischer, Rebecca Guay-Mitchell, Jeremy Jarvis, D&D LOGO DESIGN Paul Jaquays, Michael Kaluta, Dana Matt Adelsperger, Sherry Floyd Knutson, Todd Lockwood, David COVER ART Martin, Raven Mimura, Matthew Henry Higginbotham Mitchell, Monte Moore, Adam Rex, Wayne Reynolds, Richard Sardinha, INTERIOR ARTISTS Brian Snoddy, Mark Tedin, Anthony Glen Angus, Carlo Arellano, Daren Waters, Sam Wood Bader, Tom Baxa, Carl Critchlow, Brian Despain, Tony Diterlizzi, Larry Elmore, GRAPHIC -

Adobe Photoshop

I W A N T T O B I E A N A W E A book of Humor, S O Almanackery, M and Memoir E R by Ewen Cluney O B O SampleT file E W E N C L U N E Y I WANT TO BE AN AWESOME ROBOT A Book of Humor/Memoir/Almanackery By Ewen Cluney Sample file 1 ©2014 by Ewen Cluney Edited by Ellen Marlow Cover design by Clay Gardner In case it wasn’t clear, this book is a work of satire. There are true things in it, but it’s mostly lies told for comedy. Image Credits Cover Photo © 2011 by joecicak Kurumi and Maid RPG artwork by Susan Mewhiney Catgirl artwork by Thinh Pham “My Dumb Recipes” and “At the Plant” photos by Ewen Cluney Activity Section Art by Dawn Davis Ewen caricature by C. Ellis Dice photo by James Jones, used under a Creative Commons Attribution License. VCR photo by Akinom, used under a Creative Commons Attribution License. Bacon pie shell photo by nacho spiterson, used under a Creative Commons Attribution License. Infinite Loop photo by Michael Fonfara, used under a Creative Commons Attribu- tion License. Quetzalcoatl statue photo by Don DeBold, used under a Creative Commons Attribution License. Cosplay photo by Joppo Klein, used under a Creative Commons Attribution License. IBM 5150 photo by Boffy b, used under a Creative Commons Attribution License. Android OS photo by davidsancar, used under a Creative Commons Attribution License. Vladimir Putting photo by the Russian Presidential Press and Information Office, used under a Creative CommonsSample Attribution fileLicense. -

The Rise and Fall of an Open Business Model

Revue d'économie industrielle 146 | 2e trimestre 2014 Écosystèmes et modèles d'affaires The Rise and Fall of an Open Business Model Benoît Demil and Xavier Lecocq Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/rei/5803 DOI: 10.4000/rei.5803 ISSN: 1773-0198 Publisher De Boeck Supérieur Printed version Date of publication: 15 May 2014 Number of pages: 85-113 ISBN: 9782804189754 ISSN: 0154-3229 Electronic reference Benoît Demil and Xavier Lecocq, « The Rise and Fall of an Open Business Model », Revue d'économie industrielle [Online], 146 | 2e trimestre 2014, Online since 15 May 2016, connection on 10 December 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/rei/5803 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/rei.5803 © Revue d’économie industrielle THE RISE AND FALL OF AN OPEN BUSINESS MODEL1 Benoît Demil, IAE de Lille – LEM (UMR CNRS 8179) Xavier Lecocq, IAE de Lille et IESEG, LEM (UMR CNRS 8179) Keywords: Open Innovation, Business Model, Value Creation, Value Capture, Performance Mots clés : Innovation ouverte, modèle économique, création de valeur, capture de valeur, performance 1. THE RISE AND FALL OF AN OPEN BUSINESS MODEL Today, business model (BM) tends to be considered as the main driver of the performance of organizations whatever their sector. The literature stresses particularly how BM innovation may disrupt competition and create competitive advantage (e.g., Casadesus-Masanell and Ricart, 2010; Giesen et al., 2007; Johnson et al., 2008; Svejenova et al., 2010). Innovation in the domain has been prolific since the advent of the Internet era and numerous examples have been analyzed such as Amazon, Google or IBM. -

Vol. I N° 1 Flanneries

Vol. I n° 1 Flanneries Vol. I, n° 1 juin 2000 Couverture : Claire Mabille Logo Flanneries : Arkayn Cartographie : Stéphane Tanguay ADVANCED DUNGEONS & DRAGONS, AD&D, GREYHAWK et WORLD OF GREYHAWK sont des marques déposées appartenant à TSR, Inc. Tous les personnages, noms et autres éléments originaux du décor de campagne WORLD OF GREYHAWK sont également des marques déposées de TSR, Inc. TSR, Inc. est une filiale de Wizards of the Coast, Inc. Sauf indications contraires, les droits d'auteurs des textes publiés dans Flanneries appartiennent exclusivement à leurs auteurs respectifs. Editorial La production de suppléments GREYHAWK a été stoppée pour la première fois en 1993 alors que d’excellents suppléments tels que The Marklands ou Iuz the Evil venaient juste de sortir. Cet arrêt imprévu fut une grande déception. A l’époque, tout laissait penser que GREYHAWK était mort et enterré. En fait, il n’en fut rien. Le 12 mai 1995, une bande de fans se faisant nommer “The Council of Greyhawk” décide de continuer à le faire vivre sur le net et publie rapidement le premier Oerth Journal. L’Oerth Journal existe toujours et ses publications sont toujours aussi intéressantes. En 1997, sentant peut-être que quelque chose est en train de leur échapper, les décideurs de TSR/WotC prennent enfin la décision de relancer les productions GREYHAWK. Tous les fans exultent. Deux suppléments majeurs sortent en 1998, The Adventure Begins et Player’s Guide to Greyhawk ; suivi d’un autre l’année suivante, The Scarlet Brotherhood. Ceux-ci sont immédiatement traduits en français. Le Monde de GREYHAWK est relancé en anglais et pour la première fois il est accessible en français. -

The Platinum Appendix

SHANNON APPELCLINE SHANNON A HISTORY OF THE ROLEPLAYING GAME INDUSTRY THE PLATINUM APPENDIX SHANNON APPELCLINE This supplement to the Designers & Dragons book series was made possible by the incredible support given to us by the backers of the Designers & Dragons Kickstarter campaign. To all our backers, a big thank you from Evil Hat! _Journeyman_ Antoine Pempie Carlos Curt Meyer Donny Van Zandt Gareth Ryder-Han- James Terry John Fiala Keith Zientek malifer Michael Rees Patrick Holloway Robert Andersson Selesias TiresiasBC ^JJ^ Anton Skovorodin Carlos de la Cruz Curtis D Carbonell Dorian rahan James Trimble John Forinash Kelly Brown Manfred Gabriel Michael Robins Patrick Martin Frosz Robert Biddle Selganor Yoster Todd 2002simon01 Antonio Miguel Morales CURTIS RICKER Doug Atkinson Garrett Rooney James Turnbull John GT Kelroy Was Here Manticore2050 Michael Ruff Nielsen Robert Biskin seraphim_72 Todd Agthe 2Die10 Games Martorell Ferriol Carlos Gustavo D. Cardillo Doug Keester Garry Jenkins James Winfield John H. Ken Manu Marron Michael Ryder Patrick McCann Robert Challenger Serge Beaumont Todd Blake 64 Oz. Games Aoren Flores Ríos D. Christopher Doug Kern Gary Buckland James Wood John Hartwell ken Bronson Manuel Pinta Michael Sauer Patrick Menard Robert Conley Sérgio Alves Todd Bogenrief 6mmWar Apocryphal Lore Carlos Ovalle Dawson Dougal Scott Gary Gin Jamie John Heerens Ken Bullock Guerrero Michael Scholl Patrick Mueller-Best Robert Daines Sergio Silvio Todd Cash 7th Dimension Games Aram Glick Carlos Rincon D. Daniel Wagner Douglas Andrew Gary Kacmarcik Jamie MacLaren John Hergenroeder Ken Ditto Manuel Siebert Michael Sean Manley Patrick Murphy Robert Dickerson Herrera Gea Todd Dyck 9thLevel Aram Zucker-Scharff caroline D.J. -

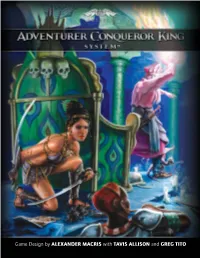

Adventurer Conqueror King System © 2011–2012 Autarch

TM Game Design by ALEXANDER MACRIS with TAVIS ALLISON and GREG TITO RULES FOR ROLEPLAYING IN A WORLD OF SWORDS, SORCERY, AND STRONGHOLDS FIRST EDITION Adventurer Conqueror King System © 2011–2012 Autarch. The Auran Empire™ and all proper names, dialogue, plots, storylines, locations, and characters relating thereto are copyright 2011 by Alexander Macris and used by Autarch™ under license. This material is protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America. Any reproduction or unauthorized use of the material or artwork contained herein is prohibited without the written permission of the copyright owners. Autarch™, Adventure Conqueror King™, Adventurer Conqueror King System™, and ACKS™ are trademarks of Autarch™. Auran Empire™ is a trademark of Alexander Macris and used by Autarch™ under license. Adventurer Conqueror King System is distributed to the hobby, toy, and comic trade in the United States by Game Salute LLC. This product is a work of fiction. Any similarity to actual people, organizations, places, or events is purely coincidental. Printed in the USA. ISBN 978-0-9849832-0-9 AUT1003.20120131.431 www.autarch.co CREDITS Lead Designer: Alexander Macris Graphic Design: Carrie Keymel Greg Lincoln Additional Design: Tavis Allison Greg Tito Intern: Chris Newman Development: Alexander Macris Kickstarter Support: Chris Hagerty Tavis Allison Timothy Hutchings Greg Tito Event Support: Tavis Allison Editing: Tshilaba Verite Ryan Browning Jonathan Steinhauer Ezra Claverie Paul Vermeren Chris Hagerty Paul Hughes Art: Ryan Browning -

Preparing for Adventure

Sample file Basic & Expert rules for roleplaying in fantastical worlds of fantasy! Editing, Layout & Writing: Anders Honoré Cover Art: Sydni Kruger Interior Art: David Revoy, Anders Honoré, David Lewis Johnson, Miguel Santos, Nathan Winburn, Bree Orlock of Stardust Publications, Rick Hershey, Vagelio Kaliva, Patrick E. Pullen, Dean Spencer & from the Public Domain Thanks to: Dave Arneson, Gary Gygax, Rob Kuntz, J. Eric Holmes, Tom Moldway, David SampleCook, Steve Marsh, Frank Mentzer, Ryan Dancey, Dan Proctor, Mikefile Mearls, Jeremy Crawford, Brendan Strejcek, Jeff Rients, Alexis Smolensk, Alex Schroeder & Eric Diaz. “Into the Unknown” is published by Anders Honoré under the Open Game License version 1.0a Copyright 2000 Wizards of the Coast, Inc. Minor modifications were made to frames and coloring of some pieces. LEGAL INFORMATION worldwide, royalty-free, non-exclusive license with the exact All quotes cited are public domain or cited under fair use. They terms of this License to Use, the Open Game Content. are in any case not open game content nor covered by the open 5. Representation of Authority to Contribute: If You are game license. contributing original material as Open Game Content, You All artwork, except for the “5e Compatible” icon, is used under represent that Your Contributions are Your original creation license or in the public domain and is not open game content nor and/or You have sufficient rights to grant the rights conveyed covered by the open game license. by this License. All art by Patrick E. Pullen is coprighted by Patrick E. Pullen. 6. Notice of License Copyright: You must update the COPYRIGHT Art from Sydni Kruger, David Lewis Johnson and David Revoy NOTICE portion of this License to include the exact text of the used under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International COPYRIGHT NOTICE of any Open Game Content You are License. -

Sample Fileyour Character Can Try to Do Anything You Can Imagine

CREDITS PLAYER’S HANDBOOK DESIGN GRAPHIC DESIGNERS Jonathan Tweet Sherry Floyd, Sean Glenn, Paul Hebron, Dawn Murin PLAYER’S HANDBOOK REVISION Andy Collins PUBLISHING PRODUCTION SPECIALISTS Carmen Cheung, Angelika Lokotz, D&D 3RD EDITION CORE DESIGN TEAM Nancy Walker Monte Cook, Jonathan Tweet, Skip Williams CARTOGRAPHER Todd Gamble D&D 3RD EDITION REVISION TEAM Richard Baker, Andy Collins, David PHOTOGRAPHER Noonan, Rich Redman, Skip Williams Craig Cudnohufsky ADDITIONAL DESIGN PREPRESS MANAGER Peter Adkison, Richard Baker Jefferson Dunlap DEVELOPMENT IMAGING TECHNICIAN Gwendolyn F.M. Kestrel, Chris Sims, Carmen Cheung Bill Slavicsek, Ed Stark PRODUCTION MANAGER EDITORS Cynda Callaway Julia Martin, John Rateliff R&D GROUP MANAGER EDITORIAL ASSISTANCE AND Mike Mearls PROOFREADING Bill McQuillan, David Noonan, D&D BRAND TEAM Jeff Quick, Penny Williams Nathan Stewart, Liz Schuh, Laura Tommervik, Shelly Mazzanoble, MANAGING EDITOR Chris Lindsay, Hilary Ross Kim Mohan OTHER WIZARDS OF THE COAST VISUAL CREATIVE DIRECTOR R&D CONTRIBUTORS Jon Schindehette Paul Barclay, Jason Carl, Michele Carter, Jennifer Clarke Wilkes, Bruce ART DIRECTOR R. Cordell, Mike Donais, David Dawn Murin Sample Eckelberry,file Skaff Elias, Andrew Finch, Jeff Grubb, Rob Heinsoo, Duane ADDITIONAL ART DIRECTION Maxwell, Christopher Perkins, Jon Kate Irwin Pickens, Sean K Reynolds, Charles Ryan, Mike Selinker, Jonathan Tweet, D&D CONCEPTUAL ARTISTS Todd Lockwood, Sam Wood James Wyatt D&D LOGO DESIGN BASED ON THE DESIGN OF Matt Adelsperger, Sherry Floyd PREVIOUS EDITIONS -

Dungeons & Dragons®

01_292907 ffirs.qxp 6/9/08 2:49 PM Page iii Dungeons & Dragons® 4th Edition FOR DUMmIES‰ by Bill Slavicsek and Richard Baker Foreword by Mike Mearls Lead Game Developer for the DUNGEONS & DRAGONS game 01_292907 ffirs.qxp 6/9/08 2:49 PM Page iv Dungeons & Dragons® 4th Edition For Dummies® Published by Wiley Publishing, Inc. 111 River Street Hoboken, NJ 07030-5774 www.wiley.com Copyright © 2008 by Wiley Publishing, Inc., Indianapolis, Indiana Published by Wiley Publishing, Inc., Indianapolis, Indiana Published simultaneously in Canada No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except as permitted under Sections 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permis- sion of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 646-8600. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Legal Department, Wiley Publishing, Inc., 10475 Crosspoint Blvd., Indianapolis, IN 46256, (317) 572-3447, fax (317) 572-4355, or online at http://www. wiley.com/go/permissions. Trademarks: Wiley, the Wiley Publishing logo, For Dummies, the Dummies Man logo, A Reference for the Rest of Us!, The Dummies Way, Dummies Daily, The Fun and Easy Way, Dummies.com, and related trade dress are trademarks or registered trademarks of John Wiley & Sons, Inc. and/or its affiliates in the United States and other countries, and may not be used without written permission. -

Dungeon Master's Guide Core Rulebook II V.3.5

® Core Rulebook II v.3.5 Based on the original Dungeons & Dragons game created by E. Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson This WIZARDS OF THE COAST® game product contains no Open Game Content. No portion of this work may be reproduced in any form without written permission. To learn more about the Open Gaming License and the d20 System License, please visit www.wizards.com/d20. U.S., CANADA, EUROPEAN HEADQUARTERS ASIA, PACIFIC, & LATIN AMERICA Wizards of the Coast, Belgium Wizards of the Coast, Inc. T Hosfveld 6d P.O. Box 707 1702 Groot-Bijgaarden Renton WA 98057-0707 Belgium Questions? 1-800-324-6496 +322- 467- 3360 620-17752-001-EN 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 First Printing: July 2003 DUNGEONS & DRAGONS, D&D, DUNGEON MASTER, d20 System, the d20 System logo, WIZARDS OF THE COAST, and the Wizards of the Coast logo are registered trademarks owned by Wizards of the Coast, Inc., a subsidiary of Hasbro, Inc. d20 is a trademark of Wizards of the Coast, Inc. Distributed to the hobby, toy, and comic trade in the United States and Canada by regional distributors. Distributed in the United States to the book trade by Holtzbrinck Publishing. Distributed in Canada to the book trade by Fenn Ltd. Distributed worldwide by Wizards of the Coast, Inc. and regional distributors. This material is protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America. Any reproduction or unauthorized use of the material or artwork contained herein is prohibited without the express written permission of Wizards of the Coast, Inc.