Pragmatism in Indian Foreign Policy: How Ideas Constrain Modi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indian Parliament Passes Anti-Tax-Evasion Bill by Stephanie Soong Johnston

Volume 78, Number 7 May 18, 2015 (C) Tax Analysts 2015. All rights reserved. Tax Analysts does not claim copyright in any public domain or third party content. Indian Parliament Passes Anti-Tax-Evasion Bill by Stephanie Soong Johnston Reprinted from Tax Notes Int’l, May 18, 2015, p. 591 (C) Tax Analysts 2015. All rights reserved. does not claim copyright in any public domain or third party content. Indian Parliament Passes dodging. ‘‘This is absolutely necessary if you are seri- ous about curbing the black money,’’ he said. Anti-Tax-Evasion Bill India has previously raised concerns about round- tripping, a strategy where Indian companies secretly by Stephanie Soong Johnston transfer funds into a country that doesn’t charge CGT, such as Mauritius, to establish residency and then bring India’s Rajya Sabha, the upper house of Parliament, the money back to India as foreign investment. on May 13 passed an anti-tax-evasion bill that would Ravishankar Raghavan of Majmudar & Partners levy a flat tax on undeclared foreign income and assets agreed that the bill doesn’t do much to prevent tax eva- and impose stricter noncompliance penalties, a move sion, but he told Tax Analysts he is concerned that Prime Minister Narendra Modi called a ‘‘historic mile- expatriates, nonresident Indians, foreign companies, stone.’’ The upper house also delayed passage of a con- and trusts that have a business connection in India stitutional bill that would pave the way for a national could fall in the tax department’s cross hairs by becom- goods and services tax regime. -

UTTAR PRADESH STATE POWER SECTOR EMPLOYEE's TRUST 24-Ashok Marg, Shakti Bhawan Vistar, Lucknow-226001

UTTAR PRADESH STATE POWER SECTOR EMPLOYEE'S TRUST 24-Ashok Marg, Shakti Bhawan Vistar, Lucknow-226001 GPF Number Generation Module Report Code : FP204 List Of GPF Number Alloted in Officer Cadre Date From : 01/04/2018 To : 31/03/2019 Sl. No. New GPF Number Name Father Name Designation Division Code , Name & Station 1 EB/O/10702 WALIUDDIN KHAN SRI ALLAH BUKSH AE 952 - ELECT CIV DISTR DIV-MEERUT 2 EB/O/10701 SHAHID MASHUQ SRI MASHUQ ALI AE 628A - ELECT WORKSHOP DIV-LUCKNOW 3 EB/O/10700 JAWAHAR LAL LATE BENI PRASAD OSD 992 - ACCOUNTS OFFICER HQ UPPCL- YADAV LUCKNOW 4 EB/O/10699 DINESH KUMAR LATE SHRI AE 390 - PARICHHA THERMAL POWER GUPTA KISHORA SHARAN PROJECT- JHANSI GUPTA 5 EB/O/10698 ALOK KHARE SRI ONKAR AAO 612 - ELECT DISTRIBUTION PRASAD KHARE CIRCLE-RAIBARELY 6 EB/O/10697 PAWAN KUMAR LATE SRI BABU AAO 166 - ZONAL ACCOUNTS OFFICER (TC)- GUPTA RAM GUPTA LUCKNOW 7 EB/O/10696 ANIL KUMAR LATE PRATAP SO 992 - ACCOUNTS OFFICER HQ UPPCL- SINGH NARAYAN SINGH LUCKNOW 8 EB/O/10695 PARAS NATH LATE TRIVENI AE 1111 - HQ UP JAL VIDUT NIGAM LTD.- YADAV YADAV LUCKNOW 9 EB/O/10694 BABU LAL LATE MEWA LAL AE 2004 - THERMAL POWER STATION OBRA PRAJAPATI "B"- OBRA 10 EB/O/10693 PAWAN KUMAR LATE SRI HARI AE 914A - ELECT DIST. DIV IV-SYANA, SINGH BULANDSHAHAR 11 EB/O/10692 KRISHAN PAL LATE RAM PAL AAO 577 - ELECT URBAN DISTR DIVSION(KD) -ALLAHABAD 12 EB/O/10691 SHIV ADHAR LATE DURGA AE 2004 - THERMAL POWER STATION OBRA PRASAD PAL "B"- OBRA 13 EB/O/10690 RAGHUPATI SRI RAM CHANDRA AE 2004 - THERMAL POWER STATION OBRA "B"- OBRA 14 EB/O/10689 JANAK DHARI LATE BUDHI RAM AE 2006 - TOWNSHIP ATPS OBRA- OBRA 15 EB/O/10688 RAKESH KUMAR LATE SRI MOTI LAL AE 390 - PARICHHA THERMAL POWER DWIVEDI DWIVEDI PROJECT- JHANSI 16 EB/O/10687 SATISH KUMAR LATE JAIRAM AE 2004 - THERMAL POWER STATION OBRA SINGH SINGH "B"- OBRA 17 EB/O/10686 YOGENDRA LATE THAN SINGH AE 489 - ELE DISTR DIVISION-I-BAREILLY SINGH 18 EB/O/10685 RAM SINGH SRI KRISHNA AE 2004 - THERMAL POWER STATION OBRA PRASAD SINGH "B"- OBRA 19 EB/O/10684 BUDH PRIYA SRI JASWANT AAO 426A - ELECT. -

The Dignity of Santana Mondal

ISSN (Online) - 2349-8846 The Dignity of Santana Mondal VIJAY PRASHAD Vol. 49, Issue No. 20, 17 May, 2014 Vijay Prashad ([email protected]) is the Edward Said Chair at the American University of Beirut, Lebanon. Santana Mondal, a dalit woman supporter of the Communist Party of India (Marxist), was attacked by Trinamool Congress men for defying their diktat and exercising her franchise. This incident illustrates the nature of the large-scale violence which has marred the 2014 Lok Sabha elections in West Bengal. Serious allegations of booth capturing and voter intimidation have been levelled against the ruling TMC. Santana Mondal, a 35 year old woman, belongs to the Arambagh Lok Sabha parliamentary constituency in Hooghly district, West Bengal. She lives in Naskarpur with her two daughters and her sister Laxmima. The sisters work as agricultural labourers. Mondal and Laxmima are supporters of the Communist Party of India-Marxist [CPI(M)], whose candidate Sakti Mohan Malik is a sitting Member of Parliament (MP). Before voting took place in the Arambagh constituency on 30 April, political activists from the ruling Trinamool Congress (TMC) had reportedly threatened everyone in the area against voting for the Left Front, of which the CPI(M) is an integral part. Mondal ignored the threats. Her nephew Pradip also disregarded the intimidation and became a polling agent for the CPI(M) at one of the booths. After voting had taken place, three political activists of the TMC visited Mondal’s home. They wanted her nephew Pradip but could not find him there. On 6 May, two days later, the men returned. -

The Pulitzer Prizes 2020 Winne

WINNERS AND FINALISTS 1917 TO PRESENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Excerpts from the Plan of Award ..............................................................2 PULITZER PRIZES IN JOURNALISM Public Service ...........................................................................................6 Reporting ...............................................................................................24 Local Reporting .....................................................................................27 Local Reporting, Edition Time ..............................................................32 Local General or Spot News Reporting ..................................................33 General News Reporting ........................................................................36 Spot News Reporting ............................................................................38 Breaking News Reporting .....................................................................39 Local Reporting, No Edition Time .......................................................45 Local Investigative or Specialized Reporting .........................................47 Investigative Reporting ..........................................................................50 Explanatory Journalism .........................................................................61 Explanatory Reporting ...........................................................................64 Specialized Reporting .............................................................................70 -

The Battle for India's Future: Democracy, Growth And

Transcript The Battle for India’s Future: Democracy, Growth and Inequality Ellen Barry International Correspondent, The New York Times James Crabtree Associate Fellow, Asia-Pacific Programme, Chatham House, Associate Professor of Practice, Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, Author, The Billionaire Raj: A Journey Through India’s New Gilded Age Shashank Joshi Senior Research Fellow, RUSI Saurabh Mukherjea CEO, Ambit Capital (2016-2018), Author, The Unusual Billionaires Chair: Dr Gareth Price Senior Research Fellow, Asia-Pacific Programme, Chatham House 3 July 2018 The views expressed in this document are the sole responsibility of the speaker(s) and participants, and do not necessarily reflect the view of Chatham House, its staff, associates or Council. Chatham House is independent and owes no allegiance to any government or to any political body. It does not take institutional positions on policy issues. This document is issued on the understanding that if any extract is used, the author(s)/speaker(s) and Chatham House should be credited, preferably with the date of the publication or details of the event. Where this document refers to or reports statements made by speakers at an event, every effort has been made to provide a fair representation of their views and opinions. The published text of speeches and presentations may differ from delivery. © The Royal Institute of International Affairs, 2018. 10 St James’s Square, London SW1Y 4LE T +44 (0)20 7957 5700 F +44 (0)20 7957 5710 www.chathamhouse.org Patron: Her Majesty The Queen Chairman: Stuart Popham QC Director: Dr Robin Niblett Charity Registration Number: 208223 2 The Battle for India’s Future: Democracy, Growth and Inequality Dr Gareth Price Okay, welcome to Chatham House everyone. -

“Product Positioning of Patanjali Ayurved Ltd.”

“PRODUCT POSITIONING OF PATANJALI AYURVED LTD.” DR. D.T. SHINDE SAILEE J. GHARAT Associate Professor Research Scholar Head, Dept. of Commerce & Accountancy K.B.P. College, Vashi, Navi K.B.P.College, Vashi, Navi Mumbai Mumbai (MS) INDIA (MS) INDIA In today’s age there is tough competition in the field of production and marketing. Instead of that we are witnessing the Brand positioning by Patanjali. Currently, Patanjali is present in almost all categories of personal care and food products ranging from soaps, shampoos, dental care, balms, skin creams, biscuits, ghee, juices, honey, mustard oil, sugar and much more. In this research paper researcher wants to study the strategies adopted by Patanjali. Keywords: Patanjali, Brand, Positioning, PAL. INTRODUCTION Objectives of the study: To study Patanjali as a brand and its product mix. To analyze and identify important factors influencing Patanjali as a brand. To understand the business prospects and working of Patanjali Ayurved Ltd To identify the future prospects of the company in comparison to other leading MNCs. Relevance of the study: The study would relevant to the young entrepreneurs for positioning of their business. It would also open the path for various research areas. Introduction: Baba Ramdev established the Patanjali Ayurved Limited in 2006 along with Acharya Balkrishna with the objective of establishing science of Ayurveda in accordance and coordinating with the latest technology and ancient wisdom. Patanjali Ayurved is perhaps the DR. D.T. SHINDE SAILEE J. GHARAT 1P a g e fastest growing fast-moving-consumer goods firm in India with Annual revenue at more than Rs 2,000 crore. -

9 Post & Telecommunications

POST AND TELECOMMUNICATIONS 441 9 Post & Telecommunications ORGANISATION The Office of the Director General of Audit, Post and Telecommunications has a chequered history and can trace its origin to 1837 when it was known as the Office of the Accountant General, Posts and Telegraphs and continued with this designation till 1978. With the departmentalisation of accounts with effect from April 1976 the designation of AGP&T was changed to Director of Audit, P&T in 1979. From July 1990 onwards it was designated as Director General of Audit, Post and Telecommunications (DGAP&T). The Central Office which is the Headquarters of DGAP&T was located in Shimla till early 1970 and thereafter it shifted to Delhi. The Director General of Audit is assisted by two Group Officers in Central Office—one in charge of Administration and other in charge of the Report Group. However, there was a difficult period from November 1993 till end of 1996 when there was only one Deputy Director for the Central office. The P&T Audit Organisation has 16 branch Audit Offices across the country; while 10 of these (located at Chennai, Delhi, Hyderabad, Kapurthala, Lucknow, Mumbai, Nagpur, Patna and Thiruvananthapuram as well as the Stores, Workshop and Telegraph Check Office, Kolkata) were headed by IA&AS Officers of the rank of Director/ Dy. Director. The charges of the remaining branch Audit Offices (located at Ahmedabad, Bangalore, Bhopal, Cuttack, Jaipur and Kolkata) were held by Directors/ Dy. Directors of one of the other branch Audit Offices (as of March 2006) as additional charge. P&T Audit organisation deals with all the three principal streams of audit viz. -

Political Parties in India

A M K RESOURCE WORLD GENERAL KNOWLEDGE www.amkresourceinfo.com Political Parties in India India has very diverse multi party political system. There are three types of political parties in Indiai.e. national parties (7), state recognized party (48) and unrecognized parties (1706). All the political parties which wish to contest local, state or national elections are required to be registered by the Election Commission of India (ECI). A recognized party enjoys privileges like reserved party symbol, free broadcast time on state run television and radio in the favour of party. Election commission asks to these national parties regarding the date of elections and receives inputs for the conduct of free and fair polls National Party: A registered party is recognised as a National Party only if it fulfils any one of the following three conditions: 1. If a party wins 2% of seats in the Lok Sabha (as of 2014, 11 seats) from at least 3 different States. 2. At a General Election to Lok Sabha or Legislative Assembly, the party polls 6% of votes in four States in addition to 4 Lok Sabha seats. 3. A party is recognised as a State Party in four or more States. The Indian political parties are categorized into two main types. National level parties and state level parties. National parties are political parties which, participate in different elections all over India. For example, Indian National Congress, Bhartiya Janata Party, Bahujan Samaj Party, Samajwadi Party, Communist Party of India, Communist Party of India (Marxist) and some other parties. State parties or regional parties are political parties which, participate in different elections but only within one 1 www.amkresourceinfo.com A M K RESOURCE WORLD GENERAL KNOWLEDGE state. -

Modi, Social Media, and Competitive Electoral Populism in India

International Journal of Communication 11(2017), 4158–4180 1932–8036/20170005 Fragile Hegemony: Modi, Social Media, and Competitive Electoral Populism in India SUBIR SINHA1 School of Oriental and African Studies, London, UK Direct and unmediated communication between the leader and the people defines and constitutes populism. I examine how social media, and communicative practices typical to it, function as sites and modes for constituting competing models of the leader, the people, and their relationship in contemporary Indian politics. Social media was mobilized for creating a parliamentary majority for Narendra Modi, who dominated this terrain and whose campaign mastered the use of different platforms to access and enroll diverse social groups into a winning coalition behind his claims to a “developmental sovereignty” ratified by “the people.” Following his victory, other parties and political formations have established substantial presence on these platforms. I examine emerging strategies of using social media to criticize and satirize Modi and offering alternative leader-people relations, thus democratizing social media. Practices of critique and its dissemination suggest the outlines of possible “counterpeople” available for enrollment in populism’s future forms. I conclude with remarks about the connection between activated citizens on social media and the fragility of hegemony in the domain of politics more generally. Keywords: Modi, populism, Twitter, WhatsApp, social media On January 24, 2017, India’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), proudly tweeted that Narendra Modi, its iconic prime minister of India, had become “the world’s most followed leader on social media” (see Figure 1). Modi’s management of—and dominance over—media and social media was a key factor contributing to his convincing win in the 2014 general election, when he led his party to a parliamentary majority, winning 31% of the votes cast. -

Public Notice-Merged.Pdf

No. 30-02/202 0-ws Government of lndia Ministry of Communications Department of Posts (PO Division) Dak Bhawan, Sansad Marg New Delhi- 110 001 Dated: 8th September, 2020 PUBLIC NOTICE SUBJECT: SEEKtNG suGGEsrloNs/FEEDBAcK/coMMENTS/|NpursrurEWs FROM GENERAL PUBLIC/STAKEHOLDERS ON THE DRAFT "INDIAN POST OFFICE RULES,2020" The central Government proposes to make a new set of lndian post office Rules' 2020 (lPo Rules, 2020) which wiil be in supersession of lpo Rures, 1933. passage 2- with the of time and induction of technorogy, the working of the post office has changed significanfly since 1933, so there is a need for a new set of rules in sync with the today's environment. 3. ln the new set of rpo Rures, 2020. some new rures have been framed, obsolete rules have been dereted from and many rures have been re- framed/modified in sync with the present scenario. The lndian post office Rules, 2020 will be a new set of Rures which wiil govern the functioning of the post offices henceforth. 4. ln the context of the above, the draft of proposed rpo Rures,2020 is hereby notified for information, seeking suggestions/feedbacucomments/inputs/views from general public/stakehorders/customers. Notice is hereby given that the suggestions/feedbacucomments/inputs/views received with regard to the said draft lPo Rules, 2020 will be taken into consideration tilr 6:00 p.m. of 9th october, 2020. 5. Suggestions/Feedback/comments/rnputsA/iews, if any, may be addressed to Ms. Sukriti Gupta, Assistant Director General (postal Operations, Room No. 340, Third Floor, Dak Bhawan, sansad Marg, New Derhi-i10001 , Ter. -

POSTAL SAVINGS Reaching Everyone in Asia

POSTAL SAVINGS Reaching Everyone in Asia Edited by Naoyuki Yoshino, José Ansón, and Matthias Helble ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK INSTITUTE Postal Savings - Reaching Everyone in Asia Edited by Naoyuki Yoshino, José Ansón, and Matthias Helble ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK INSTITUTE © 2018 Asian Development Bank Institute All rights reserved. First printed in 2018. ISBN: 978 4 89974 083 4 (Print) ISBN: 978 4 89974 084 1 (PDF) The views in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Asian Development Bank Institute (ADBI), its Advisory Council, ADB’s Board or Governors, or the governments of ADB members. ADBI does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this publication and accepts no responsibility for any consequence of their use. ADBI uses proper ADB member names and abbreviations throughout and any variation or inaccuracy, including in citations and references, should be read as referring to the correct name. By making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area, or by using the term “recognize,” “country,” or other geographical names in this publication, ADBI does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Users are restricted from reselling, redistributing, or creating derivative works without the express, written consent of ADBI. ADB recognizes “China” as the People’s Republic of China. Note: In this publication, “$” refers to US dollars. Asian Development Bank Institute Kasumigaseki Building 8F 3-2-5, Kasumigaseki, Chiyoda-ku Tokyo 100-6008, Japan www.adbi.org Contents List of illustrations v List of contributors ix List of abbreviations xi Introduction 1 Naoyuki Yoshino, José Ansón, and Matthias Helble PART I: Global Overview 1. -

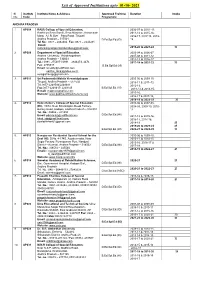

List of Approved Institutions Upto 11-08

List of Approved Institutions upto 01-10- 2021 Sl. Institute Institute Name & Address Approved Training Duration Intake No. Code Programme ANDHRA PRADESH 1. AP004 RASS College of Special Education, 2006-07 to 2010 -11, Rashtriya Seva Samiti, Seva Nilayram, Annamaiah 2011-12 to 2015-16, Marg, A.I.R. Bye – Pass Road, Tirupati, 2016-17, 2017-18, 2018- Andhra Pradesh – 517501 D.Ed.Spl.Ed.(ID) 19, Tel No.: 0877 – 2242404 Fax: 0877 – 2244281 Email: [email protected]; 2019-20 to 2023-24 30 2. AP008 Department of Special Education, 2003-04 to 2006-07 Andhra University, Vishakhapatnam 2007-08 to 2011-12 Andhra Pradesh – 530003 2012-13 to 2016-17 Tel.: 0891- 2754871 0891 – 2844473, 4474 2017-18 to 2021-22 30 Fax: 2755547 B.Ed.Spl.Ed.(VI) Email: [email protected] [email protected], [email protected] 3. AP011 Sri Padmavathi Mahila Visvavidyalayam , 2005-06 to 2009-10 Tirupati, Andhra Pradesh – 517 502 2010-11 & 2011–12 Tel:0877-2249594/2248481 2012-13, Fax:0877-2248417/ 2249145 B.Ed.Spl.Ed.(HI) 2013-14 & 2014-15, E-mail: [email protected] 2015-16, Website: www.padmavathiwomenuniv.org 2016-17 & 2017-18, 2018-19 to 2022-23 30 4. AP012 Helen Keller’s College of Special Education 2005-06 to 2007-08, (HI), 10/72, Near Shivalingam Beedi Factory, 2008-09, 2009-10, 2010- Bellary Road, Kadapa, Andhra Pradesh – 516 001 11 Tel. No.: 08562 – 241593 D.Ed.Spl.Ed.(HI) Email: [email protected] 2011-12 to 2015-16, [email protected]; 2016-17, 2017-18, [email protected] 2018-19 25 2019-20 to 2023-24 25 B.Ed.Spl.Ed.(HI) 2020-21 to 2024-25 30 5.