Taking up the Challenge of Translating Buddhism: an FPMT International Translation and Editorial Meeting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Self-Compassion: Integrating Buddhist Philosophy and Practices with Western Psychotherapy and a Group Counselling Curriculum

SELF-COMPASSION: INTEGRATING BUDDHIST PHILOSOPHY AND PRACTICES WITH WESTERN PSYCHOTHERAPY AND A GROUP COUNSELLING CURRICULUM by Amy Roomy MEd, University of Victoria, 2000 Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Curriculum Theory and Implementation Program Faculty of Education Amy Roomy 2017 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2017 Approval Name: Amy Roomy Degree: Doctor of Philosophy Title: Self-Compassion: Integrating Buddhist Philosophy and Practices with Western Psychotherapy and a Group Counselling Curriculum Examining Committee: Chair: Shawn Bullock Associate Professor Heesoon Bai Senior Supervisor Professor Charles Scott Supervisor Adjunct Professor Allan MacKinnon Internal/External Examiner Associate Professor Thupten Jinpa External Examiner Adjunct Professor School of Religious Studies McGill University Date Defended/Approved: May 18, 2017 ii Abstract In this dissertation, self-compassion and its significance to us are explored from the bifocal perspective of contemporary Western psychotherapy and Buddhist wisdom traditions containing philosophical, spiritual and psychological teachings. The dissertation explores the dialogue and synthesis that have been transpiring for the last few decades between Buddhist and Western psychological systems as proposed and practised by Buddhist and Western psychotherapists, psychiatrists and teachers on compassion and self-compassion. My personal orientation and experience of both Buddhism and the practice of Western psychotherapy serve to promote here a rich, meaningful integration and application of self-compassion in the arenas of education and human service, including schooling and mental health. Chapter 1 is a discussion of the context for my inspiration to study and research self- compassion as a Buddhist practitioner and psychotherapist. In chapter 2, I examine the Buddhist concept of self, as it is integral to the understanding of self-compassion. -

Shamatha & Vipashyana Meditation

Shamatha & Vipashyana Meditation The Core Practice Manuals Of the Indian and Tibetan Traditions An Advanced Buddhist Studies/Rime Shedra NYC Course Ten Tuesdays from September 18 to December 11, 2018, from 7-9:15 pm Shambhala Meditation Center of New York Sourcebook of Readings “All you who would protect your minds, Maintain your mindfulness and introspection; Guard them both, at cost of life and limb, I join my hands, beseeching you.” v. 3 “Examining again and yet again The state and actions of your body and your mind- This alone defines in brief The maintenance of watchful introspection.” v. 108 --Shantideva, Bodhicharyavatara, Chapter Five RIME SHEDRA CHANTS ASPIRATION In order that all sentient beings may attain Buddhahood, From my heart I take refuge in the three jewels. This was composed by Mipham. Translated by the Nalanda Translation Committee MANJUSHRI SUPPLICATION Whatever the virtues of the many fields of knowledge All are steps on the path of omniscience. May these arise in the clear mirror of intellect. O Manjushri, please accomplish this. This was specially composed by Mangala (Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche). Translated by the Nalanda Translation Committee DEDICATION OF MERIT By this merit may all obtain omniscience May it defeat the enemy, wrong doing. From the stormy waves of birth, old age, sickness and death, From the ocean of samsara, may I free all beings By the confidence of the golden sun of the great east May the lotus garden of the Rigden’s wisdom bloom, May the dark ignorance of sentient beings be dispelled. May all beings enjoy profound, brilliant glory. -

The Influence of the Contemplative on Higher Education in American (Capitalist) Culture

University of Portland Pilot Scholars Graduate Theses and Dissertations 2021 The Water In Which We Swim: The Influence of the Contemplative on Higher Education in American (Capitalist) Culture Namdrol Miranda Adams Follow this and additional works at: https://pilotscholars.up.edu/etd Part of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning Commons, and the Social and Philosophical Foundations of Education Commons Recommended Citation Adams, Namdrol Miranda, "The Water In Which We Swim: The Influence of the Contemplative on Higher Education in American (Capitalist) Culture" (2021). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 97. https://pilotscholars.up.edu/etd/97 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Pilot Scholars. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Pilot Scholars. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Water In Which We Swim: The Influence of the Contemplative on Higher Education in American (Capitalist) Culture by Namdrol Miranda Adams A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education in Leading and Learning University of Portland School of Education 2021 The Water in Which We Swim: The Influence of the Contemplative on Higher Education in American (Capitalist) Culture by Namdrol Miranda Adams This dissertation is completed as a partial requirement for the Doctor of Education (EdD) degree at the University of Portland in Portland, Oregon. Approved: REDACTED ______ ______________________ -

MAITRIPA COLLEGE COURSE CATALOG 2016 – 2017 Academic Year

MAITRIPA COLLEGE COURSE CATALOG 2016 – 2017 Academic Year Maitripa College is a non-profit corporation authorized by the State of Oregon to offer and confer the academic degrees described herein, following a determination that state academic standards will be satisfied under OAR 583-030. Inquiries concerning the standards or school compliance may be directed to the Office of Degree Authorization, Higher Education Coordinating Commission, 775 Court Street NE, Salem, Oregon 97301. TABLE OF CONTENTS GENERAL INFORMATION .................................................................................................................... 1 THE MISSION ............................................................................................................................................... 1 THE VISION .................................................................................................................................................. 1 THE EDUCATIONAL PHILOSOPHY .............................................................................................................. 2 DEVELOPING THE WISDOM TO SUSTAIN COMPASSION .................................................................................. 2 STATEMENT ON ACADEMIC FREEDOM........................................................................................................... 2 OUR HISTORY .............................................................................................................................................. 3 FACULTY & ADMINISTRATION ......................................................................................................... -

Herefore, Prajfiabecomeseven on the Research Are Professionally the Mind May Have Been Made Perceive

PRAJNA: Sharp, Illuminating, and Rationale for the Compassionate Inquisitiveness Establishment of a Network of Contemplative Observatories by KARL BRUNNHOLZL by B. ALAN WALLACE This excerpt is taken from SINCE IHH I URN OF THE CENTURY, Karl Brunnholzl's The Heart a rapidly growing number of sci- Attack Sutra, a practical and entific studies have revealed the clear explanation of The health benefits of various kinds Heart Sutra, perhaps the of mindfulness-based meditation. most well-known of the core Brain scans, EEG measurements, Buddhist texts. behavioral studies, and question- naires have shown the influence of meditation on the brain and As .the basic inquisitiveness behavior, which in the minds of and curiosity of our mind, prajna many people lends some degree is both precise and playful at the ,«****■ of credibility to the practice of same time. Iconographically it is meditation. In the overwhelm- often depicted as a double-blad- ing majority of such studies, ed, flaming sword which is ex- those who conduct and report B. Alan Wallace with Mathieu Ricard tremely sharp. Such a sword ob- (Courtesy of Mind & Life Institute, viously needs to be handled with ...a worldwide network photo by Raphaele Demandre) great care, and mav even seem of contemplative ob- somewhat threatening. servatories linked by tion, and all discoveries pertain- Prajna is indeed threatening to way of the internet, and our ego and to our cherished be- ing to meditation are claimed by ; collaborating with each lief systems since it undermines our very solid-looking objective selves. Prajna means being found- the scientists, who in many cases our verv notion of reality and reality, but it also cuts through out bv ourselves, which first of all other, modeled after the have little or no meditative expe- the reference points upon which the subjective experiencer of such requires taking an honest look at Human Genome Project. -

Sakya Chronicles 2012 May the Radiant Flower of Tibetan Tradition Be Preserved for the Benefit of All Beings

Sakya Chronicles 2012 May the radiant flower of Tibetan Tradition be preserved for the benefit of all beings. His Holiness the Dalai Lama with H.H. Jigdal Dagchen Sakya with, from left to right: H.E. Avikrita Rinpoche, H.E. Zaya Rinpoche, H.E. Asanga Rinpoche, H.E. Abhaya Rinpoche and H.E. Dagmo Kusho. Dharamsala , India Nov. 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS Tenshug for H.H. J.D. Sakya 2 H.H. J.D. Sakya’s San Francisco Teaching Trip 12 H.E. Dagmo Kusho’s California Teaching trip 3 Drokor Yeshin Korlo 14 H.E. Avikrita Rinpoche gives teachings in CA 4 Lama Choedak’s Visit 15 Dhungseys H.E. Avikrita Rinpoche and 5 H.E. Asanga Rinpoche returns to Seattle 17 H.E. Abhaya Rinpoche visit Seattle Entryway to the Dharma 19 Dharma Teens led by H.E. Avikrita Rinpoche and 7 H.E. Asanga Rinpoche gives teachings in CA 20 H.E. Abhaya Rinpoche H.E. Asanga Rinpoche and H.E. Dagmo 22 Kusho Sakya’s Travels to Vietnam Commentary by H.E. Zaya Rinpoche 7 4th Annual Live Animal Release 8 H.H.J.D. Sakya’s Asia Teaching Trip 24 Gyap-Shi Puja 9 H.E. Asanga Rinpoche teaches in Asia 30 The Heart Sutra Conference 10 Sakya Monastery Boiler Replacement Project 31 H.E. Dagmo Kusho Tara Teachings in Eugene, OR 12 Sakya Lamdre Lineage Tree 32 © 2013 Sakya Monastery of Tibetan Buddhism All rights reserved 108 NW 83rd Street, Seattle, WA 98117 • Tel: 206-789-2573 • Website: www.sakya.org • Email: [email protected] TENSHUG FOR H.H. -

How to Practice Dharma, II Explained in Detail How the FPMT Lineage Series, of Which This Book Is the Third, Came About

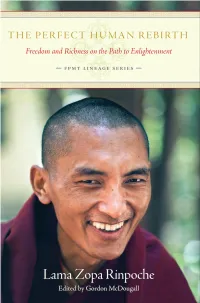

The Perfect Human Rebirth FPMT Lineage Series FPMT Lineage is a series of books of Lama Zopa Rinpoche’s teachings on the graduated path to enlightenment drawn from his four decades of dis- courses on the topic based on his own textbook, Th e Wish-fulfi lling Golden Sun, and several traditional lam-rim texts, and in general arranged according to the outline of Liberation in the Palm of Your Hand. Th is series is the most extensive contemporary lam-rim commentary available and comprises the essence of the FPMT’s education program. Th e FPMT Lineage Series is dedicated to the long life and perfect health of Lama Zopa Rinpoche, to his continuous teaching activity and to the fulfi llment of all his holy wishes. May whoever sees, touches, reads, remembers, or talks or thinks about these books never be reborn in unfortunate circumstances, receive only rebirths in situations conducive to the perfect practice of Dharma, meet only perfectly qualifi ed spiritual guides, quickly develop bodhicitta and immediately attain enlightenment for the sake of all sentient beings. FPMT Lineage Series Lama Zopa Rinpoche Th e Perfect Human Rebirth Freedom and Richness on the Path to Enlightenment Edited by Gordon McDougall Series editor Nicholas Ribush Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive • Boston www.LamaYeshe.com A non-profi t charitable organization for the benefi t of all sentient beings and an affi liate of the Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition www.fpmt.org First published 2013 Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive PO Box 636 Lincoln MA 01773, USA © Lama Th ubten Zopa Rinpoche 2013 Please do not reproduce any part of this book by any means whatsoever without our permission Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data To come Th ubten Zopa, Rinpoche, 1945- Th e perfect human rebirth : freedom and richness on the path to enlightenment / Th ubten Zopa, Rinpoche ; edited by Gordon McDougall ; series editor, Nicholas Ribush. -

Annual Report 2017 12 Pages.Indd

ANNUAL2017 REPORT Maitripa College President Yangsi Rinpoche presents an honorary Maitripa College degree to His Holiness the Dalai Lama during the 3-day Environmental Summit hosted by the College in 2013 Mission Statement Maitripa College is a Buddhist institution of higher education offering contemplative learning culminating in graduate degrees. Founded upon three pillars of scholarship, meditation, and service, Maitripa College curriculum combines Western academic and Tibetan Buddhist disciplines. Through the development of wisdom and compassion, graduates are empowered with a sense of responsibility to work joyfully for the wellbeing of others. We serve our students and the region through diverse and relevant educational, religious, and community programs. Welcome from the Dean Dear Friends, It has been another inspiring and impactful year at Maitripa College. It is hard to believe that Maitripa has been doing the work of educating hearts and minds for over a decade now; we are at once really taking root and simultaneously still so new! I was reminded of the importance of the kind of education we are offering here at Maitripa College by an experience I had recently in which I had to undergo a series of fairly invasive medical tests and exams to follow up on a previous health issue (just a check-up, everything is fi ne). During the experience of these tests, which were, superfi cially and by most standards, pretty unpleasant, I found myself repeatedly and naturally closing my eyes and directing my mind into my daily meditation practice, and, despite the unpleasantness I was experiencing, really feeling quite good. I am not a particularly disciplined or focused practitioner, but I have had a fairly consistent practice over the years, and have spent some time in meditation retreat, and like anything else it seems that the mere habit of directing the mind towards a positive state resounds. -

Dalai Lama on Environment

A B His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama on Environment Collected Statements 1987-2017 C D Dedication This book is dedicated to millions of people across the world striving for a greener, healthier and more sustainable future for our planet. - Environment & Development Desk TIBET POLICY INSTITUTE E Copyright @Environment and Development Desk,TPI First Edition March 1994 Second Edition 1995 Third Edition December 2004 Fourth and Updated Edition January 2007 Fifth and Updated Edition April 2015 Sixth and Updated Edition June 2017 No. of Copies: 1000 ISBN: 81-86627-39-1 Published by: Environment and Development Desk The Tibet Policy Institute Central Tibetan Administration Dharamsala - 176215 H.P. INDIA Tel: +91-1892-223556, 222403 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.tibet.net and www.tibetpolicy.net F The three main commitments of His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama are: * Promotion of human values, * Promotion of religious harmony, * Preservation of Tibet’s spiritual heritage and protection of its environment. G H Foreword Since 1959, His Holiness the Dalai Lama has worked tirelessly to resolve the Tibet issue with Beijing through non-violence and has been recognised the world over as one of the most revered and respected spiritual teachers, an indefatigable champion of Tibetan freedom, and a committed spokesperson for the environmental movement. His Holiness was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1989 in recognition of his non- violent struggle to resolve the Tibet issue with China, his teachings on peace, compassion and environmental conservation. According to Buddhist teachings, there is a close interdependence between the natural environment and sentient beings. -

Life, Death and After Death (PDF)

Life, Death and After Death This book is published by Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive Bringing you the teachings of Lama Yeshe and Lama Zopa Rinpoche This book is made possible by kind supporters of the Archive who, like you, appreciate how we make these teachings freely available in so many ways, including in our website for instant reading, listening or downloading, and as printed and electronic books. Our website offers immediate access to thousands of pages of teachings and hundreds of audio recordings by some of the greatest lamas of our time. Our photo gallery and our ever-popular books are also freely accessible there. Please help us increase our efforts to spread the Dharma for the happiness and benefit of all beings. You can find out more about becoming a supporter of the Archive and see all we have to offer by visiting our website at http://www.LamaYeshe.com. Thank you so much, and please enjoy this ebook. previously published by the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive Becoming Your Own Therapist, by Lama Yeshe Advice for Monks and Nuns, by Lama Yeshe and Lama Zopa Rinpoche Virtue and Reality, by Lama Zopa Rinpoche Make Your Mind an Ocean, by Lama Yeshe Teachings from the Vajrasattva Retreat, by Lama Zopa Rinpoche Daily Purification: A Short Vajrasattva Practice, by Lama Zopa Rinpoche The Essence of Tibetan Buddhism, by Lama Yeshe Making Life Meaningful, by Lama Zopa Rinpoche Teachings from the Mani Retreat, by Lama Zopa Rinpoche The Direct and Unmistaken Method, by Lama Zopa Rinpoche The Yoga of Offering Food, by Lama Zopa Rinpoche The Peaceful -

Download Download

Original Research The Long-Haul: Buddhist Educational Strategies to Strengthen Students’ Resilience for Lifelong Personal Transformation and Positive Community Change Namdrol M. Adams1 and Kevin Kecskes2 1Maitripa College, 2Department of Public Administration, Portland State University. Cite as: Adams, N.M., & Kecskes, K. (2020).The Long-Haul: Buddhist Educational Strategies to Strengthen Students’ Resilience for Lifelong Personal Transformation and Positive Community Change. Metropolitan Universities, 31(3), 140-162. DOI: 10.18060/23997 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License. Editor: Valerie L. Holton, Ph.D. Abstract For decades, community engagement scholars have built a robust body of knowledge that explores multiple facets of the higher education community engagement domain. More recently, scholars and practitioners from mainly Christian affiliated faith-based institutions have begun to investigate the complex inner world of community-engaged students’ meaning- making and spiritual development. While most of this fascinating cross-domain effort has been primarily based on “Western” influenced Judeo-Christian traditions, this study explores service- learning/community engagement themes, approaches, rationale, and strategies from an “Eastern” perspective based on the rich tradition of Tibetan Buddhism. This case study research focuses on curricular approaches, influences, and impacts of Buddhist philosophy/spirituality on community engagement endeavors in the context of -

Here Are Cess, Or Otherwise, of Our Practice Sometimes Very Graphic

PURIFICATION: Dreams, Aches, Turbulence and Other Signs of Progress by ROB PREECE Just as Jung recognized that the greater need to receive some kind find these images interesting be- psyche's way of revealing itself is of approbation that tells us we cause we can gradually learn to History of the Karmapas through dreams, so too in the Ti- are worthy or that we have spiri- read their meaning and apply it betan tradition, dreams are often tual qualities. to our life. Purification dreams considered a way of discovering Looking for signs of the suc- can be extremely diverse and Recognizing a Tulku the effect of practice. There are cess, or otherwise, of our practice sometimes very graphic. I recall even texts, referred to during the may not be particularly useful. someone in retreat saying how for the discovery of his future in- giving of empowerments, which However, as we do Buddhist she had looked down at her right Most of us know that tulkus carnation, or tulku. Writing such describe the kinds of dreams practice, we will inevitably have leg; a split opened up in it and are recognized as reincarna- a letter, which was sometimes meditators may have. In the case some experiences that do reflect exuded a mass of little insectlike tions of specific masters, but transmitted orally to a trusted of tantric practice, it is even sug- the effect of purification in par- creatures. She was horrified un- we may not know the begin- disciple, then became one of the gested that sometimes medita- ticular. It is clear from my own til she realized this image might nings of the tulku "system." methods for recognizing the Kar- tors should continue a particular experience of this, however, that actually symbolize that some- Here's the story, along with a mapas.