Governmental Regulation of Tartan and Commodification of Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Balmoral Tartan

The Balmoral Tartan Introduction The Balmoral tartan (Fig 1) is said to have been designed in 1853 by Prince Albert, The Prince Consort, Queen Victoria's husband. It is unique in several respects: it is the only tartan known to have been designed by a member of the Royal Family; has a unique construction; and is reserved for members of the Royal Family. It is worn by HM The Queen and several members of the Royal Family but only with the Queen's permission. The only other approved wearers of the Balmoral tartan are the Piper to the Sovereign and pipers on the Balmoral Estate (estate workers and ghillies wear the Balmoral tweed). Fig 1. Specimen of the original Balmoral Tartan c1865. © The Author. There is some confusion over the exact date of the original design. In 1893 D.W. Stewarti wrote, ''Her Majesty the Queen has not only granted permission for its publication here, but has also graciously afforded information concerning its inception in the early years of the reign, when the sett was designed by the Prince Consort.'' Harrison (1968) ii states that both the Balmoral tartan and Tweed were designed by Prince Albert. Writing of the tartan specimen in Stewart’s Old & Rare Harrison noted that “The illustrations were all woven in fine silk which did not allow of (sic) the reproduction of the pure black and white twist effect of the original. Mr Stewart compromised by using shades of dull mauve as the nearest that his materials allowed. Thus, for generations the Balmoral was looked upon not as a pure grey scheme but as a scheme of very quiet mauves” (Fig 2). -

Modh-Textiles-Scotland-Issue-4.Pdf

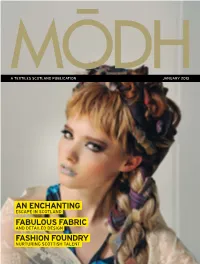

A TEXTILES SCOTLAND PUBLICATION JANUARY 2013 AN ENCHANTING ESCAPE IN SCOTLAND FABULOUS FABRIC AND DETAILED DESIGN FASHION FOUNDRY NURTURING SCOTTISH TALENT contents Editor’s Note Setting the Scene 3 Welcome from Stewart Roxburgh 21 Make a statement in any room with inspired wallpaper Ten Must-Haves for this Season An Enchanting Escape 4 Some of the cutest products on offer this season 23 A fashionable stay in Scotland Fabulous Fabric Fashion Foundry 6 Uncovering the wealth of quality fabric in Scotland 32 Inspirational hub for a new generation Fashion with Passion Devil is in the Detail 12 Guest contributor Eric Musgrave shares his 38 Dedicated craftsmanship from start to fi nish thoughts on Scottish textiles Our World of Interiors Find us 18 Guest contributor Ronda Carman on why Scotland 44 Why not get in touch – you know you want to! has the interiors market fi rmly sewn up FRONT COVER Helena wears: Jacquard Woven Plaid with Herringbone 100% Merino Wool Fabric in Hair by Calzeat; Poppy Soft Cupsilk Bra by Iona Crawford and contributors Lucynda Lace in Ivory by MYB Textiles. Thanks to: Our fi rst ever guest contributors – Eric Musgrave and Ronda Carman. Read Eric’s thoughts on the Scottish textiles industry on page 12 and Ronda’s insights on Scottish interiors on page 18. And our main photoshoot team – photographer Anna Isola Crolla and assistant Solen; creative director/stylist Chris Hunt and assistant Emma Jackson; hair-stylist Gary Lees using tecni.art by L’Oreal Professionnel and the ‘O’ and irons by Cloud Nine, and make-up artist Ana Cruzalegui using WE ARE FAUX and Nars products. -

Kilts & Tartan

Kilts & Tartan Made Easy An expert insider’s frank views and simple tips Dr Nicholas J. Fiddes Founder, Scotweb Governor, Why YOU should wear a kilt, & what kind of kilt to get How to source true quality & avoid the swindlers Find your own tartans & get the best materials Know the outfit for any event & understand accessories This e-book is my gift to you. Please copy & send it to friends! But it was a lot of work, so no plagiarism please. Note my copyright terms below. Version 2.1 – 7 November 2006 This document is copyright Dr Nicholas J. Fiddes (c) 2006. It may be freely copied and circulated only in its entirety and in its original digital format. Individual copies may be printed for personal use only. Internet links should reference the original hosting address, and not host it locally - see back page. It may not otherwise be shared, quoted or reproduced without written permission of the author. Use of any part in any other format without written permission will constitute acceptance of a legal contract for paid licensing of the entire document, at a charge of £20 UK per copy in resultant circulation, including all consequent third party copies. This will be governed by the laws of Scotland. Kilts & Tartan - Made Easy www.clan.com/kiltsandtartan (c) See copyright notice at front Page 1 Why Wear a Kilt? 4 Celebrating Celtic Heritage.................................................................................................. 4 Dressing for Special Occasions.......................................................................................... -

) Division Yours Faithfully, GARY GILLESPIE Chief Economist

Chief Economist Directorate Office of the Chief Economic Adviser (OCEA) Division <<Name>> <<Organisation>> <<Address 1>> <<Address 2>> <<Address 3>> <<Address 4>> <<Address 5>> URN: Dear << Contact >> Help us make decisions to help businesses trade locally and internationally I am writing to ask you to take part in the 20172016 ScottishScottish GlobalGlobal ConnectionsConnections SurveySurvey.. ThisThis isis the only official trade survey for Scotland, undertaken in partnership with Scottish Development International. This survey measures key indicators on the state of the Scottish economy. It helps us to measure the value and destination of sales of Scottish goods and services and the depth of international involvement of Scottish firms. To make sure the results are accurate, all types and sizes of organisation are included in the sample for this survey, including those businesses whose head offices are located outside Scotland. Even if you have no international connections, your response is still valuable to us. Once completed, please return the survey in the enclosed pre-paid envelope. Your response is appreciated by XXXXXXXXXFriday 22nd September. All information 2017 you. All provide information will be you kept provide completely will be confidential. kept Ifcompletely you have confidential.any queries please If you emailhave [email protected] queries please contact our. Alternatively helpline on you0131 can 244 contact 6803 or thee-mail helpline [email protected]. on 0131 244 6803 between 10am and 4pm. Please note you can also reply electronically. Further information can be found at: http://www.gov.scot/Topics/Statistics/Browse/Economy/Exports/GCSElectReturn. Thank you in advance for your cooperation. -

An Introduction to Policy in Scotland

POLICY GUIDE #1 2019 AN INTRODUCTION TO POLICY IN SCOTLAND This first guide provides an introduction to policymaking BES – SCOTTISH POLICY in Scotland, how policies are developed, and the difference GROUP between policy and legislation. Subsequent guides will focus on how scientists can get involved in the policy process The BES Scottish Policy Group at Holyrood and the various opportunities for evidence (SPG) is a group of British Ecological Society (BES) submission, such as to Scottish Parliament Committees. members promoting the use To find out about the policy making process at Westminster of ecological knowledge in please read the BES UK Policy Guides. Scotland. Our aim is to improve communication between BES members and policymakers, increase the impact of ecological research, and support evidence- WHAT IS A POLICY? EXAMPLES OF POLICY informed policymaking. We engage with policymaking A policy is a set of principles to Details of a policy and the steps by making the best scientific guide actions in order to achieve an needed to meet the policy ambitions evidence accessible to objective. A ‘government policy’, are often specified in Government decision-makers based on our therefore describes a course of strategies, which are usually membership expertise. action or an objective planned by developed through stakeholder the Government on a particular engagement – (i.e. Government Our Policy Guides are a resource subject. Documentation on Scottish consultations). These strategies are for scientists interested in Government policies is publicly non-binding but are often developed the policymaking process available through the Scottish to help meet binding objectives, for in Scotland and the various Government website. -

Scotland's International Framework: US Engagement Strategy

SCOTLAND’S INTERNATIONAL FRAMEWORK US ENGAGEMENT STRATEGY CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 – Why the US? – Scotland’s international ambitions – Strategic objectives for engagement with the US INFOGRAPHICS 3 STRATEGIC OBJECTIVE 1 – GLOBAL OUTLOOK 5 – Aim – Trade and Investment – Education – What is our long-term ambition? STRATEGIC OBJECTIVE 2 – 6 RELATIONSHIP AND PARTNERSHIPS – Aim – Public Diplomacy and Governmental Exchanges – Diaspora Engagement – Research, Innovation and Entrepreneurship – What is our long-term ambition? STRATEGIC OBJECTIVE 3 – 8 REPUTATION AND ATTRACTIVENESS – Aim – What is our long-term ambition? – Delivery – Additional sources and further information 9 SCOTLAND’S INTERNATIONAL FRAMEWORK US ENGAGEMENT STRATEGY 1 INTRODUCTION THE CONNECTIONS BETWEEN SCOTLAND AND THE US ARE STRONG, ENDURING, AND OF SUCH A SCALE THAT THE US HAS REMAINED SCOTLAND’S MOST SIGNIFICANT INTERNATIONAL PARTNER FOR MANY YEARS. Why the US? the challenges and opportunities posed by disruptive new technologies. These and other Historically, Scotland and the Scots have challenges are best tackled through close played a profound role in American political, collaboration, sharing our experience and the commercial and cultural life. The influence best of our expertise. and attraction of the US resonates throughout Scottish society. More than 5 million Scotland’s international ambitions Americans identify themselves as of Scottish One of the priorities of Scotland’s Economic descent, with nearly 3 million more as Scots- Strategy is internationalisation. The Trade Irish.1 This plan builds on that relationship, and Investment Strategy published in March making the most of existing connections, 2016 and the Phase 1 report of the Enterprise creating new ones, and working together with and Skills Review published in October 2016 partners in the US for our mutual benefit. -

10.92 14.99 *V

J ' •* ,. FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 10,1961 ifta Weeiheir Avenge Dally Net Preea Rm I ^ U. I8.^'WmthMr 1 TfkGK F d m i E E N r v v the VBMk Itodad ± Dim . 91. 1999 VWr mM m U tonight tea Ut MsBOhsater Child Bttt'jiy O f W 13,314 S 86. Snntoy «k*etowlng * « * ■ * , . ' Loyal CIxtila o f K w f’a Daugfetara TV, Radio, Topics Beat Tuesdsy at 1 pja- to JkXLM M W clM aM ^^ Wgkt omnf j iVifaftoy wiU meet In the FUtowaUp Itoera Hospital Notes Buckley Bdwol M br^. F U R N A C E ^ IL MMabMF.nf tiM AndM Into to dky. n gh tet tor leik AbptttTown of Center Concregmtlaoat Oburdi Of Oiild Unit Talk ^IS'subject FlU ^ ^ ABt essalt o PsEfisKr Bnnu «f OMoIntloa Monday a t 7:45 p jn . Co-hoatoaaea M o ^ Today. How Do They iB- Manchetter^A City,of ViUage Chorm Th« atpwr aub wfl » j«t- will be Mra. Clarence Peteraen and VMtfev h m an t ts S p-m flueooo CWldreBT” LT. W O O D C O . t ie i* putty tomorrow ni(ht at 8 tar an aiaaa ' vm M asatonMy R ol^ Dlgwi. M aaolieatpr • t O M U t Mlaa Dorothy PeUraen. A baby-sltttog oervloo tot (GtaMlfM AdvmtWng an Pngn t) •mCE'FIVB CEN«’;'f^:,!| e’dock. publte la Invited. wkan ihsy an t <e « : » aai 8188 seiwol attsBdaaee oftlowr, wiU be school ohlldreo wlU be avaUable at YdL. LXXX, NO. 112 (TEN PA^^S—TV 8®CrnON--SUBU|ffl||A TODAY) MANCHESTER, c 6n n \ SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 1\,.19C1 T Army PrL James A. -

Scotland and the UK Constitution

Scotland and the UK Constitution The 1998 devolution acts brought about the most significant change in the constitution of the United Kingdom since at least the passage of the 1972 European Communities Act. Under those statutes devolved legislatures and administrations were created in Wales, Northern Ireland, and Scotland. The documents below have been selected to give an overview of the constitutional settlement established by the devolution acts and by the Courts. Scotland has been chosen as a case study for this examination, both because the Scottish Parliament has been granted the most extensive range of powers and legislative competences of the three devolved areas, but also because the ongoing debate on Scottish independence means that the powers and competencies of the Scottish Parliament are very much live questions. The devolution of certain legislative and political powers to Scotland was effected by the Scotland Act 1998. That statute, enacted by the Westminster Parliament, creates the Scottish Parliament and the Scottish Executive (now the “Scottish Government”), and establishes the limits on the Parliament’s legislative competence. Schedule 5 of the Act, interpolated by Section 30(1), lists those powers which are reserved to the Westminster Parliament, and delegates all other matters to the devolved organs. Thus, while constitutional matters, foreign affairs, and national defence are explicitly reserved to Westminster, all matters not listed— including the education system, the health service, the legal system, environmental -

![[Tweed and Textiles from Early Times to the Present Day]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8427/tweed-and-textiles-from-early-times-to-the-present-day-678427.webp)

[Tweed and Textiles from Early Times to the Present Day]

[Tweed and Textiles from Early Times to the Present Day] The crofting way of life as it was lived in the Calbost area occupied the time of the whole population; both male and female during the four seasons of the year in a fully diversified way of life. Their work alternated from agriculture, fishing, kelping, weaving and knitting, cattle and sheep etc. etc. Some of that work was seasonal and some work was carried on inside during the winter months when it was difficult to participate in outdoor work because of the weather and the long winter evenings. Distaff – ‘Cuigeal’ The manufacture of cloth on order to protect him from the elements was one of man’s most ancient occupations and spinning was carried out by the distaff and spindle from an early date, yet it is believed that the distaff is still in use in parts of the world today. The distaff was also used extensively in Lewis in times past. A distaff is simply a 3 ft x 1½ inch rounded piece of wood with about 8 inches of one end flattened in order to hold the wool on the outer end as the distaff protrudes out in front of the spinner as she held it under her arm with a tuft of wool at the end. The wool from the distaff was then linked to the spindle ‘Dealgan’ or ‘Fearsaid’ which is held in the opposite hand and given a sharp twist by the fingers at the top of the spindle, in order to put the twist in the yarn as the spindle rotates in a suspended position hanging from the head. -

The Scottish Bar: the Evolution of the Faculty of Advocates in Its Historical Setting, 28 La

Louisiana Law Review Volume 28 | Number 2 February 1968 The cottS ish Bar: The volutE ion of the Faculty of Advocates in Its Historical Setting Nan Wilson Repository Citation Nan Wilson, The Scottish Bar: The Evolution of the Faculty of Advocates in Its Historical Setting, 28 La. L. Rev. (1968) Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/lalrev/vol28/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Louisiana Law Review by an authorized editor of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE SCOTTISH BAR: THE EVOLUTION OF THE FACULTY OF ADVOCATES IN ITS HISTORICAL SOCIAL SETTING Nan Wilson* Although the expression "advocate" is used in early Scottish statutes such as the Act of 1424, c. 45, which provided for legal aid to the indigent, the Faculty of Advocates as such dates from 1532 when the Court of Session was constituted as a College of Justice. Before this time, though friends of litigants could appear as unpaid amateurs, there had, of course, been professional lawyers, lay and ecclesiastical, variously described as "fore- speakers," procurators and prolocutors. The functions of advo- cate and solicitor had not yet been differentiated, though the notary had been for historical reasons. The law teacher was then essentially an ecclesiastic. As early as 1455, a distinctive costume (a green tabard) for pleaders was prescribed by Act of Parliament.' Between 1496 and 1501, at least a dozen pleaders can be identified as in extensive practice before the highest courts, and procurators appeared regularly in the Sheriff Courts.2 The position of notary also flourished in Scotland as on the Continent, though from 1469 the King asserted the exclusive right to appoint candidates for that branch of legal practice. -

University of Southampton Research Repository

University of Southampton Research Repository Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis and, where applicable, any accompanying data are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis and the accompanying data cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content of the thesis and accompanying research data (where applicable) must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder/s. When referring to this thesis and any accompanying data, full bibliographic details must be given, e.g. Thesis: Author (Year of Submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University Faculty or School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. Data: Author (Year) Title. URI [dataset] University of Southampton Faculty of Arts and Humanities Winchester School of Art Banal and Splendid Form: revaluing textile makers’ social and poetic identity as a strategy for textile manufacturing innovation Volume 1 by Clio Padovani Critical commentary for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy July 2019 University of Southampton Abstract Faculty of Arts and Humanities Winchester School of Art Critical commentary for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Banal and Splendid Form: revaluing textile makers’ social and poetic identity as a strategy for textile manufacturing innovation by Clio Padovani This is a submission for the Award of PhD by Published Works. The commentary on three published submissions organises a programme of work focussed on reframing traditional textile craft skills within the context of innovation and knowledge exchange policies. -

THE ORIGINS of the “Mccrackens”

THE ORIGINS OF THE “McCrackens” By Philip D. Smith, Jr. PhD, FSTS, GTS, FSA Scot “B’e a’Ghaidhlig an canan na h’Albanaich” – “Gaelic was the language of the Scottish people.” The McCrackens are originally Scottish and speakers of the Scottish Gaelic language, a cousin to Irish Gaelic. While today, Gaelic is only spoken by a few thousands, it was the language of most of the people of the north and west of Scotland until after 1900. The McCracken history comes from a long tradition passed from generation to generation by the “seannachies”, the oral historians, of the Gaelic speaking peoples. According to tradition, the family is named for Nachten, Lord of Moray, a district in the northeast of Scotland. Nachten supposedly lived in the 9th century. In the course of time a number of his descendants moved southwest across Scotland and settled in Argyll. The family multiplied and prospered. The Gaelic word for “son” is “mac” and that for “children” is “clann” The descendants of Nachten were called by their neighbors, the Campbells, MacDougalls, and others the “Children of the Son of Nachten”, in Gaelic “Cloinne MacNachtain”, “Clan MacNachtan”. Spelling was not regularized in either Scotland or America until well after 1800. Two spellings alternate for the guttural /k/-like sound common in many Gaelic words, -ch and –gh. /ch/ is the most common Scottish spelling but the sound may be spelled –gh. The Scottish word for “lake” is “loch” while in Northern England and Ireland the same word is spelled “lough”. “MacLachlan” and “Mac Loughlin” are the same name as are “Docherty” and “Dougherty”.