Adas Torah Journal of Torah Ideas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Path to Follow a Hevrat Pinto Publication Pikudei 381

The Path To Follow A Hevrat Pinto Publication Pikudei 381 Under the Direction of Rabbi David H. Pinto Shlita Adar I 29th 5771 www.hevratpinto.org | [email protected] th Editor-in-Chief: Hanania Soussan March 5 2011 32 rue du Plateau 75019 Paris, France • Tel: +331 48 03 53 89 • Fax: +331 42 06 00 33 Rabbi David Pinto Shlita Batei Midrashim As A Refuge Against The Evil Inclination is written, “These are the accounts of the Sanctuary, the Sanctuary of Moreover, what a person studies will only stay with him if he studies in a Beit Testimony” (Shemot 38:21). Our Sages explain that the Sanctuary was HaMidrash, as it is written: “A covenant has been sealed concerning what we a testimony for Israel that Hashem had forgiven them for the sin of the learn in the Beit HaMidrash, such that it will not be quickly forgotten” (Yerushalmi, golden calf. Moreover, the Midrash (Tanchuma, Pekudei 2) explains Berachot 5:1). I have often seen men enter a place of study without the intention that until the sin of the golden calf, G-d dwelled among the Children of of learning, but simply to look at what was happening there. Yet they eventually ItIsrael. After the sin, however, His anger prevented Him from dwelling among them. take a book in hand and sit down among the students. This can only be due to the The nations would then say that He was no longer returning to His people, and sound of the Torah and its power, a sound that emerges from Batei Midrashim and therefore to show the nations that this would not be the case, He told the Children conquers their evil inclination, lighting a spark in the heart of man so he begins to of Israel: “Let them make Me a Sanctuary, that I may dwell among them” (Shemot study. -

Chanukahsale

swwxc ANDswwxc swwxc CHANUKAH SALE * CHANUKAH 20% OFF ALL SALEswwxc ARTSCROLL PUBLICATIONS PLUS SHABSI’S CHANUKAH SPECIALS° א פרייליכען חנוכה SALE NOW THRU DEC. 31ST, 2019 *20% off List Price °While Supplies Last swwxc ALL CHANUKAH 2,000+ TITLES swwxc list SALE 20% OFFprice Let the Sar HaTorah, Maran Rav Chaim Kanievsky shlita, enrich your Shabbos table. by Rabbi Shai Graucher As we read through Rav Chaim Kanievsky on Chumash, we can almost hear the voice of this incomparable gadol b’Yisrael, in his Torah insights, his guidance in matters large and small, and in the stories, warm and personal, of Rav Chaim and his illustrious family. Rabbi Shai Graucher is an almost-daily visitor to Rav Chaim. He pored through all of Rav Chaim’s many Torah writings, learned with him, and collected Rav Chaim’s insights and comments on the Chumash, translated and adapted for maximum readability and clarity. Rav Chaim Kanievsky on Chumash is an instant classic, a sefer that belongs on every Shabbos table. Bereishis $25.99 NOW ONLY $20.79 Shemos $25.99 NOW ONLY $20.79 For the Entire Family — Bring the Parashah to Life! THE Weekly Parashah by Rabbi Nachman Zakon illustrated by Tova Katz This unique narrative retelling of the Chumash is designed to engage readers ages 8 and up. Written by an educator with decades of experience, it will instill in the hearts of young people a love for Torah and a commitment to Jewish tradition and values. Based on the Chumash text, classic commentators, and the Midrash, The Weekly Parashah features age-appropriate text and graphics, gorgeous illustrations, and dozens of short sidebars that enhance the reading experience. -

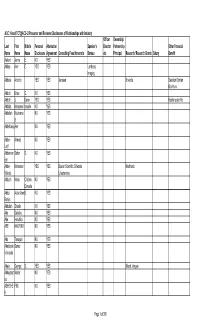

ACC14 and Tctacci2 Presenter and Reviewer Disclosures B.Pdf

ACC.14 and TCT@ACC-i2 Presenter and Reviewer Disclosures of Relationships with Industry Officer Ownership Last First Middle Personal Attestation Speaker's Director Partnership Other Financial Name Name Name Disclosure Agreement Consulting Fees Honoraria Bureau etc Principal Research/ Research Grants Salary Benefit Aaland Jenna E. NO YES Abbas Amr E. YES YES Lantheus Imaging Abbate Antonio YES YES Janssen Novartis Swedish Orphan Biovitrum Abbott Brian G. NO YES Abbott J. Dawn YES YES Boston scientific Abdalla Mohamed Ismaile NO YES Abdallah Mouhama NO YES d Abdelbaky Amr NO YES Abdel- Ahmed NO YES Latif Abdelmon Sahar S. NO YES eim Abdel- Mohamed YES YES Boston Scientific, Edwards Medtronic Wahab Lifesciences Abduch Maria Cristina NO YES Donadio Abdul Aizai Azan B. NO YES Rahim Abdullah Shuaib NO YES Abe Daisuke NO YES Abe Haruhiko NO YES ABE NAOYUKI NO YES Abe Takayuki NO YES Abedzade Sanaz NO YES h Anaraki Abela George S. YES YES Merck, Amgen Abhayarat Walter NO YES na ABHISHE FNU NO YES K Page 1 of 350 Officer Ownership Last First Middle Personal Attestation Speaker's Director Partnership Other Financial Name Name Name Disclosure Agreement Consulting Fees Honoraria Bureau etc Principal Research/ Research Grants Salary Benefit Abidi Syed NO YES Abidov Aiden NO YES Abi-samra Freddy Michel NO YES Abizaid Alexandre YES YES Abbott, Boston Scientific Abo- Elsayed NO YES Salem Abou- Alex NO YES Chebl AbouEzze Omar F NO YES ddine Aboulhosn Jamil A. YES YES GE Medical, Actelion United Therapeutics, Actelion Pharmaceuticals Pharmaceuticals Abraham Jacob NO YES Abraham JoEllyn Moore NO YES Abraham Maria Roselle NO YES Abraham Theodore P. -

400 Editor RABBI SHIMON HELINGER

ב"ה למען ישמעו • פרשת תצוה • 400 EDITOR RABBI SHIMON HELINGER PURIM A POTENT DAY INTENSE REJOICING The Rebbe once said: It’s obvious that we must distance ourselves entirely The Zohar notes that Purim is similar to Yom We read in the Gemara that on Purim one must drink from anything negative (“cursed be Haman”), HaKipurim. This means that what is accomplished “until he cannot differentiate (“ad d’lo yada”) between and seek to treasure and embrace all good things on Yom Kippur by fasting can be accomplished ‘cursed be Haman’ and ‘blessed be Mordechai.’ ” (“blessed be Mordechai”). That applies at any time. on Purim by rejoicing. Furthermore, the very The Gemara relates a story of two amoraim, Rabbah The unique aspect of Purim is that we can accomplish name Kipurim (“like Purim”), implies that Purim and Rav Zeira, who had their Purim seuda together, this by allowing our neshama to express itself freely. is the greater Yom-Tov, impacting a person sharing profound secrets of the Torah over a This kind of avoda is superior to serving HaShem by more powerfully. number of cups of wine. However, Rav Zeira was so means of conscious thought (yada). Indeed, in this Indeed, Chazal teach that when Moshiach comes, all overwhelmed by the intense kedusha of Rabbah’s kind of avoda we can resemble the Yidden at the the Yomim-Tovim will cease to exist; only the Yom- revelations that his neshama left his body. time of the Purim story who, when the inner power Tov of Purim will remain. Chassidus explains that of their neshamos surfaced, fulfilled all the mitzvos the joy and holiness of Purim are so great, that even faithfully, even to the point of mesiras nefesh. -

Women, Relationships & Jewish Texts

WOMEN, RELATIONSHIPS sukkot& JEWISH TEXTS Rethinking Sukkot: Women, Relationships and Jewish Texts a project of jwi.org/clergy © Jewish Women International 2019 Shalom Colleagues and Friends, On behalf of the Clergy Task Force, we are delighted to offer this newly revised resource to enrich Sukkot celebra- tions. Rethinking Sukkot: Women, Relationships and Jewish Texts is designed to spark new conversations about iconic relationships by taking a fresh look at old texts. Using the text of Kohelet, which is read on the Shabbat that falls during Sukkot, as well as prayers, midrash, and modern commentary, the guide serves to foster conversations about relationships. It combines respectful readings with provocative and perceptive insights, questions and ideas that can help shape healthier relationships. We hope it will be warmly received and widely used throughout the Jewish community. We are grateful to our many organizational partners for their assistance and support in distributing this resource in preparation for the observance of Sukkot. We deeply appreciate the work of the entire Clergy Task Force and want to especially acknowledge Rabbi Donna Kirshbaum, co-editor of this guide, and each of the contributors for their thoughtful commentaries. Please visit jwi.org/clergy to learn more about the important work of the Task Force. We welcome your reactions to this resource, and hope you will use it in many settings. Wishing you a joyful Sukkot, Rabbi Leah Citrin Rabbi David Rosenberg Co-Chair, Clergy Task Force Co-Chair, Clergy Task Force Lori Weinstein Deborah Rosenbloom CEO, JWI Vice President of Programs & New Initiatives, JWI MEMBERS Rabbi Leah Citrin (co-chair) Rabbi Joshua Rabin Temple Beth Or, Raleigh, NC United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism, New York, NY Rabbi Sean Gorman Pride of Israel Synagogue, Toronto, ON Rabbi Nicole K. -

1 Jews, Gentiles, and the Modern Egalitarian Ethos

Jews, Gentiles, and the Modern Egalitarian Ethos: Some Tentative Thoughts David Berger The deep and systemic tension between contemporary egalitarianism and many authoritative Jewish texts about gentiles takes varying forms. Most Orthodox Jews remain untroubled by some aspects of this tension, understanding that Judaism’s affirmation of chosenness and hierarchy can inspire and ennoble without denigrating others. In other instances, affirmations of metaphysical differences between Jews and gentiles can take a form that makes many of us uncomfortable, but we have the legitimate option of regarding them as non-authoritative. Finally and most disturbing, there are positions affirmed by standard halakhic sources from the Talmud to the Shulhan Arukh that apparently stand in stark contrast to values taken for granted in the modern West and taught in other sections of the Torah itself. Let me begin with a few brief observations about the first two categories and proceed to somewhat more extended ruminations about the third. Critics ranging from medieval Christians to Mordecai Kaplan have directed withering fire at the doctrine of the chosenness of Israel. Nonetheless, if we examine an overarching pattern in the earliest chapters of the Torah, we discover, I believe, that this choice emerges in a universalist context. The famous statement in the Mishnah (Sanhedrin 4:5) that Adam was created singly so that no one would be able to say, “My father is greater than yours” underscores the universality of the original divine intent. While we can never know the purpose of creation, one plausible objective in light of the narrative in Genesis is the opportunity to actualize the values of justice and lovingkindness through the behavior of creatures who subordinate themselves to the will 1 of God. -

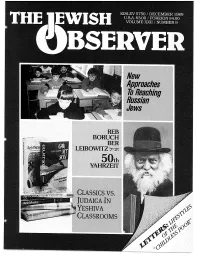

Israel of America, 5 Beekman Street, New York, N

FIFTY CENTS VOL. 2 No. 3 DECEMBER 1964 I TEVES 5725 THE "American Orthodoxy" Yesterday and Today • The Orthodox Jew and The Negro Revolution •• ' The Professor' and Bar Ilan • Second Looks at The Jewish Scene THE JEWISH QBSERVER contents articles "AMERICAN ORTHODOXY" I YESTERDAY AND TODAY, Yaakov Jacobs 3 A CENTRAL ORTHODOX AGENCY, A Position Paper .................... 9 HARAV CHAIM MORDECAI KATZ, An Appreciation ........................ 11 THE JEWISH OBSERVER is published monthly, except July and August, ASPIRATION FOR TORAH, Harav Chaim Mordecai Katz 12 by the Agudath Israel of America, 5 Beekman Street, New York, N. Y. 10038. Second class postage paid at New York, N. Y. THE ORTHODOX JEW AND THE NEGRO REVOLUTION, Subscription: $5.00 per year; single copy: 50¢. Printed in the Marvin Schick 15 U.S.A. THE PROFESSOR AND BAR JI.AN, Meyer Levi .................................... 18 Editorial Board DR. ERNST L. BODENHFJMER Chairman RABBI NATHAN BULMAN RABBI JOSEPH ELIAS JOSEPH FRIEDENSON features RABBI MORRIS SHERER Art Editor BOOK REVIEW ................................................. 20 BERNARD MERI.ING Advertising Manager RABBI SYSHE HESCHEL SECOND LOOKS AT THE JEWISH SCENE ................................................... 22 Managing Editor RABBI Y AAKOV JACOBS THE JEWISH OBSERVER does not assume responsibility for the Kashrus of any product or service the cover advertised in its pages. HARAV CHAIM MORDECAI KATZ dedicating the new dormitory of the Telshe DEC. 1964 VOL. II, No. 3 Yeshiva, and eulogizing the two young students who perished in the fire ~'@> which destroyed the old structure. (See AN APPRECIATION on page 11, and ASPIRATION FOR TORAH on page 12.) OrthudoxJudaism in ih~ Uniied States in our ··rei~oval oi the women's gallery; or th;c~nfirma~· · . -

Rabbi Eliezer Levin, ?"YT: Mussar Personified RABBI YOSEF C

il1lj:' .N1'lN1N1' invites you to join us in paying tribute to the memory of ,,,.. SAMUEL AND RENEE REICHMANN n·y Through their renowned benevolence and generosity they have nobly benefited the Torah community at large and have strengthened and sustained Yeshiva Yesodei Hatorah here in Toronto. Their legendary accomplishments have earned the respect and gratitude of all those whose lives they have touched. Special Honorees Rabbi Menachem Adler Mr. & Mrs. Menachem Wagner AVODASHAKODfSHAWARD MESORES A VOS AW ARD RESERVE YOUR AD IN OUR TRIBUTE DINNER JOURNAL Tribute Dinner to be held June 3, 1992 Diamond Page $50,000 Platinum Page $36, 000 Gold Page $25,000 Silver Page $18,000 Bronze Page $10,000 Parchment $ 5,000 Tribute Page $3,600 Half Page $500 Memoriam Page '$2,500 Quarter Page $250 Chai Page $1,800 Greeting $180 Full Page $1,000 Advertising Deadline is May 1. 1992 Mall or fax ad copy to: REICHMANN ENDOWMENT FUND FOR YYH 77 Glen Rush Boulevard, Toronto, Ontario M5N 2T8 (416) 787-1101 or Fax (416) 787-9044 GRATITUDE TO THE PAST + CONFIDENCE IN THE FUTURE THEIEWISH ()BSERVER THE JEWISH OBSERVER (ISSN) 0021 -6615 is published monthly except July and August by theAgudath Israel of America, 84 William Street, New York, N.Y. 10038. Second class postage paid in New York, N.Y. LESSONS IN AN ERA OF RAPID CHANGE Subscription $22.00 per year; two years, $36.00; three years, $48.00. Outside of the United States (US funds drawn on a US bank only) $1 O.00 6 surcharge per year. -

Dvar Tora from Shabbat Naso, 5774

Divine Favoritism? R. Yaakov Bieler Parashat Naso, 5774 Birchat Kohanim appears in Parashat Naso. One of the most well-known passages of the Tora, due to its being recited both inside and outside the synagogue, appears in this week’s Parasha: BaMidbar 6:22-27 Speak unto Aharon and unto his sons, saying: In this way ye shall bless the children of Israel; ye shall say unto them: The Lord Bless thee, and Keep thee; The Lord Make His Face to Shine upon thee, and be Gracious unto thee; The Lord Lift up His Countenance upon thee, and Give thee peace. So shall they put My Name upon the children of Israel, and I will Bless them.' When Birchat Kohanim is invoked. Kohanim directly bless the people living in Israel daily each time the Amida is repeated, and in Chutz LaAretz on Yom Tov; the Shliach Tzibbur (prayer leader for the congregation) in the diaspora regularly invokes these blessings in Chazarat HaShaTz (the repetition of the Silent Devotion); and parents bestow these blessings on their children on Friday nights and Erev Yom HaKippurim both inside and outside Israel. A difficulty with an implication of these Berachot. Despite how well-known and often recited these particularly blessings may be, the Talmud startlingly points to one portion of this famous text and challenges it as unjust, and even hypocritical: Berachot 20b R. 'Avira discoursed — sometimes in the name of R. Ammi, and sometimes in the name of R. Assi — as follows: The Ministering Angels said before the Holy One, Blessed Be He: Sovereign of the Universe, it is written in Thy Law, (Devarim 10:17) “Who Regardeth not persons nor Taketh reward”,1 and dost Thou not (overly) Regard the person of Israel, as it is written, (BaMidbar 6:26) “The Lord Lift up His Countenance upon thee”?2 1 For the LORD your God, He is God of gods, and Lord of lords, the Great God, the Mighty, and the Awful, Who Regardeth not persons, nor Taketh reward. -

Hebrew Printed Books and Manuscripts

HEBREW PRINTED BOOKS AND MANUSCRIPTS .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. SELECTIONS FROM FROM THE THE RARE BOOK ROOM OF THE JEWS’COLLEGE LIBRARY, LONDON K ESTENBAUM & COMPANY TUESDAY, MARCH 30TH, 2004 K ESTENBAUM & COMPANY . Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art Lot 51 Catalogue of HEBREW PRINTED BOOKS AND MANUSCRIPTS . SELECTIONS FROM THE RARE BOOK ROOM OF THE JEWS’COLLEGE LIBRARY, LONDON Sold by Order of the Trustees The Third Portion (With Additions) To be Offered for Sale by Auction on Tuesday, 30th March, 2004 (NOTE CHANGE OF SALE DATE) at 3:00 pm precisely ——— Viewing Beforehand on Sunday, 28th March: 10 am–5:30 pm Monday, 29th March: 10 am–6 pm Tuesday, 30th March: 10 am–2:30 pm Important Notice: The Exhibition and Sale will take place in our new Galleries located at 12 West 27th Street, 13th Floor, New York City. This Sale may be referred to as “Winnington” Sale Number Twenty Three. Catalogues: $35 • $42 (Overseas) Hebrew Index Available on Request KESTENBAUM & COMPANY Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art . 12 West 27th Street, 13th Floor, New York, NY 10001 ¥ Tel: 212 366-1197 ¥ Fax: 212 366-1368 E-mail: [email protected] ¥ World Wide Web Site: www.kestenbaum.net K ESTENBAUM & COMPANY . Chairman: Daniel E. Kestenbaum Operations Manager & Client Accounts: Margaret M. Williams Press & Public Relations: Jackie Insel Printed Books: Rabbi Belazel Naor Manuscripts & Autographed Letters: Rabbi Eliezer Katzman Ceremonial Art: Aviva J. Hoch (Consultant) Catalogue Photography: Anthony Leonardo Auctioneer: Harmer F. Johnson (NYCDCA License no. 0691878) ❧ ❧ ❧ For all inquiries relating to this sale, please contact: Daniel E. -

Temple Emanu-El Newsletter

Temple Emanu-El TEN Newsletter ISDN I E TEN VOLUME 92 NUMBER 2 | FEBRUARY - JUNE 2018 | SHEVAT/ADAR/NISAN/IYYAR/SIVAN/TAMUZ 5778 2 Letters 4 B’nai Mitzvahs Choice: The Foundation of Freedom 7 Contributions by Rabbi David-Seth Kirshner 14 Holidays 18 Upcoming Events 26 Sisterhood Chocolate or Vanilla? Democrat or Republican? Jersey Shore or the Hamptons? Our lives are full of choices. Some are trivial and will have very little impact on 29 Men’s Club the shaping of our future. Other decisions like who we marry, taking a specific job or moving to a new city all provide a different fundamental canvas that allows for the portrait of our lives to be painted. Sometimes, even the simplest decision of taking the day off on September 11, or missing a flight can make all of the impact that you could never anticipate. READ THE FULL MESSAGE FROM RABBI KIRSHNER ON THE NEXT PAGE > A LETTER FROM OUR RAbbI Choice: The Foundation of Freedom Chocolate or Vanilla? Democrat or Republican? Jersey Shore or the Hamptons? Our lives are full of choices. Some are trivial and will have very little impact on the shaping of our future. Other decisions like who we marry, taking a specific job or moving to a new city all provide a different fundamental canvas that allows for the portrait of our lives to be painted. Sometimes, even the simplest decision of taking the day off on September 11, or missing a flight can make all of the impact that you could never anticipate. Choice is rarely appreciated. -

JO1989-V22-N09.Pdf

Not ,iv.st a cheese, a traa1t1on... ~~ Haolam, the most trusted name in Cholov Yisroel Kosher Cheese. Cholov Yisroel A reputation earned through 25 years of scrupulous devotion and kashruth. With 12 delicious varieties. Haolam, a tradition you'll enjoy keeping. A!I Haolam Cheese products are under the strict Rabbinical supervision of: ~ SWITZERLAND The Rabbinate of K'hal Ada th Jeshurun Rabbi Avrohom Y. Schlesinger Washington Heights. NY Geneva, Switzerland THl'RM BRUS WORLD CHFf~~ECO lNC. 1'!-:W YORK. 1-'Y • The Thurm/Sherer Families wish Klal Yisroel n~1)n 1)J~'>'''>1£l N you can trust ... It has to be the new, improved parve Mi dal unsalted margarine r~~ In the Middle of Boro Park Are Special Families. They Are Waiting For A Miracle It hurts ... bearing a sick and helpless child. where-even among the finest families in our It hurts more ... not being able to give it the community. Many families are still waiting for proper care. the miracle of Mishkon. It hurts even more ... the turmoil suffered by Only you can make that miracle happen. the brothers and sisters. Mishkon. They are our children. Mishkon is helping not only its disabled resident Join in Mishkon's campaign to construct a children; it is rescuing the siblings, parents new facility on its campus to accommodate entire families from the upheaval caused by caring additional children. All contributions are for a handicapped child at home. tax-deductible. Dedication opportunities Retardation and debilitation strikes every- are available. Call 718-851-7100. Mishkon: They are our children.