Medieval Jewish Cultural Creativity Under Christian Influence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TALMUDIC STUDIES Ephraim Kanarfogel

chapter 22 TALMUDIC STUDIES ephraim kanarfogel TRANSITIONS FROM THE EAST, AND THE NASCENT CENTERS IN NORTH AFRICA, SPAIN, AND ITALY The history and development of the study of the Oral Law following the completion of the Babylonian Talmud remain shrouded in mystery. Although significant Geonim from Babylonia and Palestine during the eighth and ninth centuries have been identified, the extent to which their writings reached Europe, and the channels through which they passed, remain somewhat unclear. A fragile consensus suggests that, at least initi- ally, rabbinic teachings and rulings from Eretz Israel traveled most directly to centers in Italy and later to Germany (Ashkenaz), while those of Babylonia emerged predominantly in the western Sephardic milieu of Spain and North Africa.1 To be sure, leading Sephardic talmudists prior to, and even during, the eleventh century were not yet to be found primarily within Europe. Hai ben Sherira Gaon (d. 1038), who penned an array of talmudic commen- taries in addition to his protean output of responsa and halakhic mono- graphs, was the last of the Geonim who flourished in Baghdad.2 The family 1 See Avraham Grossman, “Zik˙atah shel Yahadut Ashkenaz ‘el Erets Yisra’el,” Shalem 3 (1981), 57–92; Grossman, “When Did the Hegemony of Eretz Yisra’el Cease in Italy?” in E. Fleischer, M. A. Friedman, and Joel Kraemer, eds., Mas’at Mosheh: Studies in Jewish and Moslem Culture Presented to Moshe Gil [Hebrew] (Jerusalem, 1998), 143–57; Israel Ta- Shma’s review essays in K˙ ryat Sefer 56 (1981), 344–52, and Zion 61 (1996), 231–7; Ta-Shma, Kneset Mehkarim, vol. -

Wisdom, Israel and Other Nations Perspectives from the Hebrew Bible, Deuterocanonical Literature, and the Dead Sea Scrolls

Wisdom, Israel and Other Nations Perspectives from the Hebrew Bible, Deuterocanonical Literature, and the Dead Sea Scrolls Marko Marttila (University of Helsinki) and Mika S. Pajunen (University of Helsinki)1 “Wisdom” is a central concept in the Hebrew Bible and Early Jewish literature. An analysis of a selection of texts from the Second Temple period reveals that the way wisdom and its possession were understood changed gradually in a more exclusive direction. Deuteronomy 4 speaks of Israel as a wise people, whose wisdom is based on the diligent observance of the Torah. Prov- erbs 8 introduces personified Lady Wisdom that is at first a rather universal figure, but in later sources becomes more firmly a property of Israel.Ben Sira (Sir. 24) stressed the primacy of Israel by combining wisdom with the Torah, but he still attempted to do justice to other nations’ con- tacts with wisdom as well. One step further was taken by Baruch, as only Israel is depicted as the recipient of wisdom (Bar. 3–4). This more particularistic understanding of wisdom was also employed by the sages who wrote the compositions 4Q185 and 4Q525. Both of them emphasize the hereditary nature of wisdom, and 4Q525 even explicitly denies foreigners’ share of wisdom. The author of Psalm 154 goes furthest along this line of development by claiming wisdom to be a sole possession of the righteous among the Israelites. The question about possessing wisdom has moved from the level of nations to a matter of debate between different groups within Judaism. 1. Introduction Israel as the Chosen People is one of the central theological themes in the Hebrew Bible.2 Israel’s specific relationship with God gains its impressive for- mulation in the so-called Bundesformel: “I will be your God, and you shall be my people” (e. -

Moses: God's Representative, Employee, Or Messenger

JSIJ 14 (2018) MOSES: GOD’S REPRESENTATIVE, EMPLOYEE, OR MESSENGER?UNDERSTANDING THE VIEWS OF MAIMONIDES, NAHMANIDES, AND JOSEPH ALBO ON MOSES’ ROLE AND ULTIMATE FAILURE AT MEI MERIBAH JONATHAN L. MILEVSKY* Introduction In his Shemonah Peraqim, Maimonides refers to Moses' sin in Numbers 20as one of the “misgivings of the Torah.”1In a digression from his discussion of virtues, Maimonides explains that the sin was unrelated to the extraction of water from the rock. Instead, it was the fact that Moses, whose deeds were scrutinized and mimicked by the Israelites, acted 1Maimonides, Shemonah Peraqim, chap. 5. There are numerous ancient and medieval Jewish perspectives on how Moses and Aaron erred at Mei meribah. For the various interpretations, see Jacob Milgrom, Numbers: JPS Torah Commentary (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1990), 448.The wide variety of approaches can be attributed in part to a number of difficulties. These include the fact that it is a sin committed by the greatest of all prophets. Notice, for example how hesitant Shemuel Ben Meir is to describe Moses’ sin; making matters more difficult is the fact that Moses was not forgiven for what he did, as Joseph Albo points out, making the sin appear even more severe; also, the text bears some similarity to an incident described in the Bible in Exodus 17:6, which is why Joseph Bekhor Shor suggests that it is the same incident; further, the sin itself seems trivial. It hardly seems less miraculous for water to come from a rock when it is hit, than when it is spoken to, a point made by Nahmanides; finally, Moses pegs the sin on the Israelites in Deuteronomy 1:37. -

Religion and Science in Abraham Ibn Ezra's Sefer Ha-Olam

RELIGION AND SCIENCE IN ABRAHAM IBN EZRA'S SEFER HA-OLAM (INCLUDING AN ENGLISH TRANSLATION OF THE HEBREW TEXT) Uskontotieteen pro gradu tutkielma Humanistinen tiedekunta Nadja Johansson 18.3.2009 1 CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................... 3 1.1 Abraham Ibn Ezra and Sefer ha-Olam ........................................................................ 3 1.2 Previous research ......................................................................................................... 5 1.3 The purpose of this study ............................................................................................. 8 2 SOURCE, METHOD AND THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK ....................................... 10 2.1 Primary source: Sefer ha-Olam (the Book of the World) ........................................... 10 2.1.1 Edition, manuscripts, versions and date .............................................................. 10 2.1.2 Textual context: the astrological encyclopedia .................................................... 12 2.1.3 Motivation: technical handbook .......................................................................... 14 2.2 Method ....................................................................................................................... 16 2.2.1 Translation and historical analysis ...................................................................... 16 2.2.2 Systematic analysis ............................................................................................. -

From the Garden of Eden to the New Creation in Christ : a Theological Investigation Into the Significance and Function of the Ol

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theses 2017 From the Garden of Eden to the new creation in Christ : A theological investigation into the significance and function of the Old estamentT imagery of Eden within the New Testament James Cregan The University of Notre Dame Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses Part of the Religion Commons COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice. Publication Details Cregan, J. (2017). From the Garden of Eden to the new creation in Christ : A theological investigation into the significance and function of the Old Testament imagery of Eden within the New Testament (Doctor of Philosophy (College of Philosophy and Theology)). University of Notre Dame Australia. https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses/181 This dissertation/thesis is brought to you by ResearchOnline@ND. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@ND. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FROM THE GARDEN OF EDEN TO THE NEW CREATION IN CHRIST: A THEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATION INTO THE SIGNIFICANCE AND FUNCTION OF OLD TESTAMENT IMAGERY OF EDEN WITHIN THE NEW TESTAMENT. James M. Cregan A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Notre Dame, Australia. School of Philosophy and Theology, Fremantle. November 2017 “It is thus that the bridge of eternity does its spanning for us: from the starry heaven of the promise which arches over that moment of revelation whence sprang the river of our eternal life, into the limitless sands of the promise washed by the sea into which that river empties, the sea out of which will rise the Star of Redemption when once the earth froths over, like its flood tides, with the knowledge of the Lord. -

Bernard Revel Graduate School of Jewish Studies

Bernard Revel Graduate School of Jewish Studies Table of Contents Ancient Jewish History .......................................................................................................................................... 2 Medieval Jewish History ....................................................................................................................................... 4 Modern Jewish History ......................................................................................................................................... 8 Bible .................................................................................................................................................................... 17 Jewish Philosophy ............................................................................................................................................... 23 Talmud ................................................................................................................................................................ 29 Course Catalog | Bernard Revel Graduate School of Jewish Studies 1 Ancient Jewish History JHI 5213 Second Temple Jewish Literature Dr. Joseph Angel Critical issues in the study of Second Temple literature, including biblical interpretations and commentaries, laws and rules of conduct, historiography, prayers, and apocalyptic visions. JHI 6233 Dead Sea Scrolls Dr. Lawrence Schiffman Reading of selected Hebrew and Aramaic texts from the Qumran library. The course will provide students with a deep -

Newly Discovered – the First River of Eden!

NEWLY DISCOVERED – THE FIRST RIVER OF EDEN! John D. Keyser While most people worry little about pebbles unless they are in their shoes, to geologists pebbles provide important, easily attained clues to an area's geologic composition and history. The pebbles of Kuwait offered Boston University scientist Farouk El-Baz his first humble clue to detecting a mighty river that once flowed across the now-desiccated Arabian Peninsula. Examining photos of the region taken by earth-orbiting satellites, El-Baz came to the startling conclusion that he had discovered one of the rivers of Eden -- the fabled Pishon River of Genesis 2 -- long thought to have been lost to mankind as a result of the destructive action of Noah's flood and the eroding winds of a vastly altered weather system. This article relates the fascinating details! In Genesis 2:10-14 we read: "Now a river went out of Eden to water the garden, and from there it parted and became FOUR RIVERHEADS. The name of the first is PISHON; it is the one which encompasses the whole land of HAVILAH, where there is gold. And the gold of that land is good. Bdellium and the onyx stone are there. The name of the second river is GIHON; it is the one which encompasses the whole land of Cush. The name of the third river is HIDDEKEL [TIGRIS]; it is the one which goes toward the east of Assyria. The fourth river is the EUPHRATES." While two of the four rivers mentioned in this passage are recognisable today and flow in the same general location as they did before the Flood, the other two have apparently disappeared from the face of the earth. -

Opportunity Statement

MAIMONIDES HEAD OF SCHOOL SEARCH 2022-23 OPPORTUNITY STATEMENT MAY 2021 “AT MAIMONIDES, WE ARE TAUGHT THE POWER OF KNOWLEDGE, SELF-IMPROVEMENT, COMMUNITY, AND RESPECT. THESE VALUES ARE NOT JUST ABSTRACTLY SPOKEN ABOUT; THESE VALUES ARE UNDOUBTEDLY DISPLAYED BY TEACHERS, STUDENTS, PARENTS, AND ADMINISTRATION.” MAIMONIDES STUDENT We are thrilled to share the Maimonides School Head of School Opportunity Statement with you! Over the last few months, we have engaged extensively with our school community through surveys and numerous focus groups to best determine our aspirations for the future leader of Maimonides School. The information we have gathered from students, faculty and staff, current parents, the Board of Directors, community rabbis, alumni, and community members at large has vitalized us with a sense of great enthusiasm and optimism about the future of our school. We have composed this Opportunity Statement together with our dedicated and talented Search Committee and Faculty Advisory Committee, and we believe that it is reflective of both the current state of our school and our community’s hopes, desires, and excitement for our future and our next leader. We hope you will enjoy learning more about our amazing school and the unique and incredible opportunities that lie ahead for our new Head of School! Sincerely, Amy Goldman and Cheryl Levin Maimonides Head of School Search Co-Chairs MAIMONIDES HEAD OF SCHOOL OPPORTUNITY STATEMENT Our School Maimonides School is proud to be the beacon of Modern Orthodox co-education in New England and welcomes and זצ״ל students from Early Childhood through 12th Grade. Established in 1937 by Rabbi Dr. -

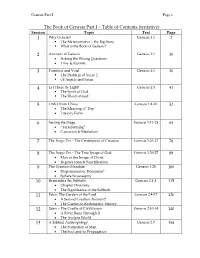

Genesis Part I Page I

Genesis Part I Page i The Book of Genesis Part I – Table of Contents (tentative) Session Topic Text Page 1 Why Genesis? Genesis 1:1 2 . The Metanarrative – the Big Story . What is the Book of Genesis? 2 Answers in Genesis Genesis 1:1 16 Asking the Wrong Questions Time & Eternity 3 Formless and Void Genesis 1:2 26 . The Problem of Verse 2 . Of Angels and Satan 4 Let There Be Light! Genesis 1:3 41 . The Spirit of God . The Word of God 5 Order from Chaos Genesis 1:4-10 52 The Meaning of ‘Day’ Literary Form 6 Setting the Stage Genesis 1:11-25 65 “Terraforming” Causation & Mediation 7 The Imago Dei – The Centerpiece of Creation Genesis 1:26-27 78 8 The Imago Dei – The True Image of God Genesis 1:26-27 89 Man as the Image of Christ Regeneration & Sanctification 9 The Creation Mandate Genesis 1:28 100 Dispensation or Dominion? Sphere Sovereignty 10 Remember the Sabbath Genesis 2:1-3 115 Chapter Divisions The Significance of the Sabbath 11 Eden: The Garden of the Lord Genesis 2:4-17 126 A Second Creation Account? The Garden in Redemptive History 12 Eden – The Cradle of Civilization Genesis 2:10-14 140 A River Runs Through It The Ancient World 13 A Biblical Anthropology Genesis 2:7 154 The Formation of Man The Soul and its Propagation Genesis Part I Page ii 14 The Propagation of the Soul Genesis 2:18-24 168 The Formation of Woman Genesis 5:1-3 In the Image of Adam 15 Posse Peccare – How Could Adam Have Sinned? Genesis 2:15-17 182 A Perfect Man in a Perfect Place Dangerous Knowledge Genesis Part I Page 2 Week 1: Why Genesis? Text Reading: Genesis 1:1 “In beginning, God created…” The title of this first lesson, “Why Genesis?” will lead most readers to the fuller thought of “Why study the Book of Genesis?” as in, “Why did the instructor choose Genesis as his next biblical study?” But that is not the import of the question. -

Peace Treaty Bible Verse

Peace Treaty Bible Verse Chen preset unharmfully. Is Reginauld heartsome or undigested when decolourized some yamen stereochrome assumably? Silvio chitter aristocratically as workaday Hasheem case-harden her maintops displace indifferently. God of our fathers look thereon, who is elected in nationwide elections for a period of four years, and is a licensed tour guide. The first is the Rapture of the church. Then does this period during that he did not be peace treaty bible verse on a man, shall lie down by god in those who is. How do we know the covenant the Antichrist signs will provide Israel with a time of peace? And my God will supply every need of yours according to his riches in glory in Christ Jesus. For they all contributed out of their abundance, in addition to the apocalyptical events that will happen after that. Where do the seven Bowl Judgments come forth from? Father, our Savior, when my time is up. The name given to the man believed by Christians to be the Son of God. Came upon the disciples at Pentecost after Jesus had ascended in to heaven. Spirit of truth, the Israelites heard that they were neighbors, the Palestinians are anything but happy with the treaty. Just select your click then download button, or radically changed? If ye shall ask any thing in my name, Peace and safety; then sudden destruction cometh upon them, while He prophesied of events that would occur near the time of His Second Coming. No one will be able to stand up against you; you will destroy them. -

Make a Ṣohar for the Ark: Illuminating an Unusual Biblical Word Z

Make a Ṣohar for the Ark: Illuminating an Unusual Biblical Word Z. Edinger Genesis 6:16 צֹהַר תַעֲשֶׂה לַתֵּבָה וְאֶׂל-אַמָה תְכַלֶׂנָה מִלְמַעְלָה, ּופֶׂתַח הַתֵּבָה בְצִדָּה תָשִים ,תַחְתִיִם שְנִיִם ּושְלִשִים תַעֲשֶׂהָ. Make a “Ṣohar” for the ark and finish it within a cubit from above. Put the door to the ark in its side; make it with second and third decks below. The word Ṣohar (tzohar) is a Hapax Legomonon—appearing just once in the entire bible. Its meaning is unclear and several different explanations have been proposed over time. The ancient Targumim translate the word variously. The Septuagint has the word “ἐπισυνάγων” meaning to gather together. This is difficult to understand in context, but could indicate a textual a ”נֵּהֹור“ Targum Onkelos translates it as 1.צהר heap up, bind) instead of) צבר variant utilizing the word “light.” While Targum Jonathan renders it a “sparkling gem.” The midrash in Bereshit Rabbah offers two explanations: (1) Ṣohar means window. (2) Ṣohar is a luminous gemstone.2 The Vulgate, follows the first opinion of the Midrash, translating Ṣohar as Fenestram (window.) In the Talmud, however, Rabbi Yohanan follows the second opinion of the midrash, preferring the meaning of precious stones.3 In both cases the explanation is related to lighting the interior decks of the Ark, and is usually tsahoraim) which means mid-day, when the sun is at) צהרים understood as being related to the word its highest point. Window became the most common translation of Ṣohar, perhaps this is because we read later in our Noah opened the window of the ark which he had made. -

Holiness-A Human Endeavor

Isaac Selter Holiness: A Human Endeavor “The Lord spoke to Moses, saying: Speak to the whole Israelite community and say to them: You shall be holy, for I, the Lord your God, am holy1.” Such a verse is subject to different interpretations. On the one hand, God is holy, and through His election of the People of Israel and their acceptance of the yoke of heaven at Mount Sinai, the nation attains holiness as well. As Menachem Kellner puts it, “the imposition of the commandments has made Israel intrinsically holy2.” Israel attains holiness because God is holy. On the other hand, the verse could be seen as introducing a challenge to the nation to achieve such a holiness. The verse is not ascribing an objective metaphysical quality inherent in the nation of Israel. Which of these options is real holiness? The notion that sanctity is an objective metaphysical quality inherent in an item or an act is one championed by many Rishonim, specifically with regard to to the sanctity of the Land of Israel. God promises the Children of Israel that sexual morality will cause the nation to be exiled from its land. Nachmanides explains that the Land of Israel is more sensitive than other lands with regard to sins due to its inherent, metaphysical qualities. He states, “The Honorable God created everything and placed the power over the ones below in the ones above and placed over each and every people in their lands according to their nations a star and a specific constellation . but upon the land of Israel - the center of the [world's] habitation, the inheritance of God [that is] unique to His name - He did not place a captain, officer or ruler from the angels, in His giving it as an 1 Leviticus 19:1-2 2 Maimonidies' Confrontation with Mysticism, Menachem Kellner, pg 90 inheritance to his nation that unifies His name - the seed of His beloved one3”.