Cheering Or Jeering?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liberal Base 'Less Than Enthusiastic' As PM Trudeau Prepares to Defend

Big Canadian challenge: the world is changing in Health disruptive + powerful + policy transformative briefi ng ways, & we better get HOH pp. 13-31 a grip on it p. 12 p.2 Hill Climbers p.39 THIRTIETH YEAR, NO. 1602 CANADA’S POLITICS AND GOVERNMENT NEWSPAPER MONDAY, FEBRUARY 4, 2019 $5.00 News Liberals News Election 2019 News Foreign policy House sitting last Trudeau opportunity for Liberal base ‘less than ‘masterful’ at Trudeau Liberals soft power, to highlight enthusiastic’ as PM falling short on achievements, hard power, says control the Trudeau prepares to ex-diplomat agenda and the Rowswell message, says a defend four-year record BY PETER MAZEREEUW leading pollster rime Minister Justin Trudeau Phas shown himself to be one to ‘volatile electorate,’ of the best-ever Canadian leaders BY ABBAS RANA at projecting “soft power” on the world stage, but his government’s ith the Liberals and Con- lack of focus on “hard power” servatives running neck W is being called into question as and neck in public opinion polls, say Liberal insiders Canada sits in the crosshairs of the 13-week sitting of the House the world’s two superpowers, says is the last opportunity for the The federal Liberals are heading into the next election with some members of the a former longtime diplomat. Continued on page 35 base feeling upset that the party hasn’t recognized their eff orts, while it has given Continued on page 34 special treatment to a few people with friends in the PMO, say Liberal insiders. Prime News Cybercrime Minister News Canada-China relations Justin Trudeau will RCMP inundated be leading his party into Appointing a the October by cybercrime election to special envoy defend his reports, with government’s a chance for four-year little success in record before ‘moral suasion’ a volatile prosecution, electorate. -

ONLINE INCIVILITY and ABUSE in CANADIAN POLITICS Chris

ONLINE INCIVILITY AND ABUSE IN CANADIAN POLITICS Chris Tenove Heidi Tworek TROLLED ON THE CAMPAIGN TRAIL ONLINE INCIVILITY AND ABUSE IN CANADIAN POLITICS CHRIS TENOVE • HEIDI TWOREK COPYRIGHT Copyright © 2020 Chris Tenove; Heidi Tworek; Centre for the Study of Democratic Institutions, University of British Columbia. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. CITATION Tenove, Chris, and Heidi Tworek (2020) Trolled on the Campaign Trail: Online Incivility and Abuse in Canadian Politics. Vancouver: Centre for the Study of Democratic Institutions, University of British Columbia. CONTACT DETAILS Chris Tenove, [email protected] (Corresponding author) Heidi Tworek, [email protected] CONTENTS AUTHOR BIOGRAPHIES ..................................................................................................................1 RESEARCHERS ...............................................................................................................................1 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ...................................................................................................................2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................3 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................5 FACING INCIVILITY IN #ELXN43 ....................................................................................................8 -

Chong Favoured in Conservative Leadership Contest

Chong Favoured in Conservative Leadership Contest Chong and Raitt favoured among party members, Half want “someone else" TORONTO December 8th – In a random sampling of public opinion taken by the Forum Poll among 1304 Canadian voters, Michael Chong leads preference for a Conservative leader among the general public (10%), followed by Lisa Raitt (8%), Michael Chong leads Kellie Leitch (7%), Chris Alexander (6%) and Maxime Bernier (5%) and Steve preference for a Blaney (5%). Andrew Scheer (3%) and Brad Trost (2%) have less support. Other Conservative leader candidates were excluded for brevity. among the general public It must be pointed out that fully half the sample opts for “someone else” (53%), (10%), followed by Lisa other than the 8 candidates listed. Raitt (8%), Kellie Leitch (7%), Chris Alexander (6%) Among Conservative voters, there is no clear favourite, and Chris Alexander (8%), and Maxime Bernier (5%) Steve Blaney (9%), Michael Chong (8%) and Lisa Raitt (8%) are evenly matched. and Steve Blaney (5%) One half choose “someone else”. “We are drawing closer to Among a very small sample of Conservative Party members (n=65), Raitt (12%) the Leadership and Chong (10%) are tied, and followed by Chris Alexander (9%) and Kellie Leitch Convention, and (8%). One half want “someone else” (48%). interested voters have had “We are drawing closer to the Leadership Convention, and interested voters have the chance to see two had the chance to see two debates now. Yet, Conservatives still haven’t seen the debates now. Yet, candidate they want, and one half won’t support any of the people running," said Conservatives still haven’t Forum Research President, Dr. -

1 1. As You May Know, Andrew Scheer Has Resigned As Leader the Conservative Party of Canada

1_1. As you may know, Andrew Scheer has resigned as leader the Conservative Party of Canada. A vote will be held in August among party members to elect a new leader. The following people are running for the leadership of the federal Conservative Party. For each one, please indicate how favourable you are towards them. - Peter MacKay REGION HOUSEHOLD INCOME HOUSEHOLD Date of completion COMPOSITION Total BC AB SK/MB Ontario Quebec Atlantic <$40K $40K - $60K - $100K+ Kids No Kids August August <$60K <$100K 17th 18th A B C D E F G H I J K L M N Base: All Respondents (unwtd) 2001 241 200 197 702 461 200 525 357 555 391 453 1548 1000 1001 Base: All Respondents (wtd) 2001 268 226 124 770 478 134 626 388 492 309 425 1576 973 1028 550 70 67 31 206 118 58 139 104 165 107 121 429 275 275 Favourable 28% 26% 29% 25% 27% 25% 44% 22% 27% 34% 35% 28% 27% 28% 27% ABCDE G GH 471 62 57 31 206 85 30 149 87 119 76 93 378 232 238 Unfavourable 24% 23% 25% 25% 27% 18% 22% 24% 22% 24% 25% 22% 24% 24% 23% E 980 137 102 62 359 274 46 339 197 208 126 211 769 466 514 Don't know enough about them to have an informed opinion 49% 51% 45% 50% 47% 57% 34% 54% 51% 42% 41% 50% 49% 48% 50% F F F BDF IJ IJ 2001 268 226 124 770 478 134 626 388 492 309 425 1576 973 1028 Sigma 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% Statistics: Overlap formulae used - Column Proportions: Columns Tested (5%): A/B/C/D/E/F,G/H/I/J,K/L,M/N Minimum Base: 30 (**), Small Base: 100 (*) - Column Means: Columns Tested (5%): A/B/C/D/E/F,G/H/I/J,K/L,M/N Minimum Base: 30 (**), Small Base: 100 (*) 1_2. -

Core 1..24 Committee

House of Commons CANADA Standing Committee on Procedure and House Affairs PROC Ï NUMBER 013 Ï 2nd SESSION Ï 39th PARLIAMENT EVIDENCE Thursday, January 31, 2008 Chair Mr. Gary Goodyear Also available on the Parliament of Canada Web Site at the following address: http://www.parl.gc.ca 1 Standing Committee on Procedure and House Affairs Thursday, January 31, 2008 Ï (1105) equal representation, which further compounds the problem, in my [English] view. The Chair (Mr. Gary Goodyear (Cambridge, CPC)): I That notwithstanding, it does appear that the steering committee recognize you, Mr. Lukiwski. has determined, in its infinite wisdom, that legislation is not a priority for this committee, that they wish to discuss Madam Let me welcome everybody back after the holidays. I hope you all Redman's motion. had a productive time in your ridings. On behalf of, I'm sure, other members of the committee, I wish all of you a very happy, With that in mind, I have a motion, Chair. I apologize, because it prosperous, and safe new year. was rather hastily written and it's handwritten, because it just occurred in the last few moments. But I'd like to read it. It's only in Colleagues, this morning I want to present the steering English, not in both official languages. I assume the clerk will be committee's report. The steering committee met earlier this week able to get the correct translation. I would like to read it into the and drafted the second report of the subcommittee on agenda and record. procedure of the Standing Committee on Procedure and House Affairs. -

A Layman's Guide to the Palestinian-Israeli Conflict

CJPME’s Vote 2019 Elections Guide « Vote 2019 » Guide électoral de CJPMO A Guide to Canadian Federal Parties’ Positions on the Middle East Guide sur la position des partis fédéraux canadiens à propos du Moyen-Orient Assembled by Canadians for Justice and Peace in the Middle East Préparé par Canadiens pour la justice et la paix au Moyen-Orient September, 2019 / septembre 2019 © Canadians for Justice and Peace in the Middle East Preface Préface Canadians for Justice and Peace in the Middle East Canadiens pour la paix et la justice au Moyen-Orient (CJPME) is pleased to provide the present guide on (CJPMO) est heureuse de vous présenter ce guide Canadian Federal parties’ positions on the Middle électoral portant sur les positions adoptées par les East. While much has happened since the last partis fédéraux canadiens sur le Moyen-Orient. Canadian Federal elections in 2015, CJPME has Beaucoup d’eau a coulé sous les ponts depuis les élections fédérales de 2015, ce qui n’a pas empêché done its best to evaluate and qualify each party’s CJPMO d’établir 13 enjeux clés relativement au response to thirteen core Middle East issues. Moyen-Orient et d’évaluer les positions prônées par chacun des partis vis-à-vis de ceux-ci. CJPME is a grassroots, secular, non-partisan organization working to empower Canadians of all CJPMO est une organisation de terrain non-partisane backgrounds to promote justice, development and et séculière visant à donner aux Canadiens de tous peace in the Middle East. We provide this horizons les moyens de promouvoir la justice, le document so that you – a Canadian citizen or développement et la paix au Moyen-Orient. -

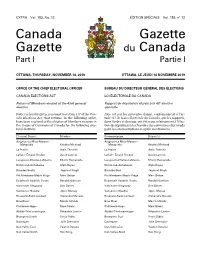

Canada Gazette, Part I

EXTRA Vol. 153, No. 12 ÉDITION SPÉCIALE Vol. 153, no 12 Canada Gazette Gazette du Canada Part I Partie I OTTAWA, THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 14, 2019 OTTAWA, LE JEUDI 14 NOVEMBRE 2019 OFFICE OF THE CHIEF ELECTORAL OFFICER BUREAU DU DIRECTEUR GÉNÉRAL DES ÉLECTIONS CANADA ELECTIONS ACT LOI ÉLECTORALE DU CANADA Return of Members elected at the 43rd general Rapport de député(e)s élu(e)s à la 43e élection election générale Notice is hereby given, pursuant to section 317 of the Can- Avis est par les présentes donné, conformément à l’ar- ada Elections Act, that returns, in the following order, ticle 317 de la Loi électorale du Canada, que les rapports, have been received of the election of Members to serve in dans l’ordre ci-dessous, ont été reçus relativement à l’élec- the House of Commons of Canada for the following elec- tion de député(e)s à la Chambre des communes du Canada toral districts: pour les circonscriptions ci-après mentionnées : Electoral District Member Circonscription Député(e) Avignon–La Mitis–Matane– Avignon–La Mitis–Matane– Matapédia Kristina Michaud Matapédia Kristina Michaud La Prairie Alain Therrien La Prairie Alain Therrien LaSalle–Émard–Verdun David Lametti LaSalle–Émard–Verdun David Lametti Longueuil–Charles-LeMoyne Sherry Romanado Longueuil–Charles-LeMoyne Sherry Romanado Richmond–Arthabaska Alain Rayes Richmond–Arthabaska Alain Rayes Burnaby South Jagmeet Singh Burnaby-Sud Jagmeet Singh Pitt Meadows–Maple Ridge Marc Dalton Pitt Meadows–Maple Ridge Marc Dalton Esquimalt–Saanich–Sooke Randall Garrison Esquimalt–Saanich–Sooke -

2019 Federal Election: Result and Analysis

2019 Federal Election: Result and Analysis O C T O B E R 22, 2 0 1 9 NATIONAL ELECTION RESULTS 157 121 24 3 32 (-20) (+26) (-15) (+1) (+22) Comparison between results reflected based on party standings at dissolution of the 42nd parliament • The Liberal Party of Canada (LPC) won a second mandate, although was diminished to minority status. • The result of the 43rd Canadian election is one of the closest in recent memory, with both the Liberals and Conservatives separated by little more than one percentage point. Conservatives share of vote is slightly higher than the Liberals, making major gains in key areas for the party • Bloc Quebecois (BQ) is a winner in this election, moving up to official party status which will give the party added resources as well as significance in the House of Commons • The NDP managed to win enough seats to potentially play an important role in the House of Commons, but the party took a big hit in Quebec — where they were only able to hold one of the Layton era “Orange Wave” seats • Maxime Bernier, who started the People’s Party of Canada after narrowly losing the Conservative leadership contest in 2017, lost the seat he has held onto since 2006 • The former Treasury Board president Dr. Jane Philpott, who ran as an independent following her departure from the liberal caucus, lost her seat in Markham Stouffville to former Liberal MPP and Ontario Minister of Health, Dr. Helena Jaczek. Jody Wilson-Raybould won as an independent in Vancouver Granville NATIONAL ELECTION RESULTS 10 2 32 3 39 24 PARTY STANDINGS AT -

What to Do About Question Period: a Roundtable

What to do about Question Period: A Roundtable Michael Chong, MP; Marlene Jennings, MP; Mario Laframboise, MP; Libby Davies, MP; Tom Lukiwski, MP On May 7, 2010 a motion calling for the Standing Committee on Procedure and House Affairs to recommend changes to the Standing Orders and other conventions governing Oral Questions was introduced by the member for Wellington–Halton Hills. Among other things the Committee would consider ways of (i) elevating decorum and fortifying the use of discipline by the Speaker, to strengthen the dignity and authority of the House, (ii) lengthening the amount of time given for each question and each answer, (iii) examining the convention that the Minister questioned need not respond, (iv) allocating half the questions each day for Members, whose names and order of recognition would be randomly selected, (v) dedicating Wednesday exclusively for questions to the Prime Minister, (vi) dedicating Monday, Tuesday, Thursday and Friday for questions to Ministers other than the Prime Minister in a way that would require Ministers be present two of the four days to answer questions concerning their portfolio, based on a published schedule that would rotate and that would ensure an equitable distribution of Ministers across the four days. The motion was debated on May 27, 2010. The following extracts are taken from that debate. Michal Chong (Conservative, Wel- Since this motion was made public, I have received lington–Halton Hills): Canadians phone calls, letters and emails from citizens across know that something is not quite right this country. From Kingston, a proud member of the with their democratic institutions. -

Canada This Month Public Opinion Research Release Date: July 22, 2020 Federal Politics Field Dates: July 14 to July 20, 2020

Canada This Month Public Opinion Research Release Date: July 22, 2020 Federal Politics Field Dates: July 14 to July 20, 2020 STRICTLY PRIVILEGED AND CONFIDENTIAL 2 Federal Politics in the time of COVID-19 The COVID-19 outbreak has set off a series of changes in the Canadian political landscape. Federally, approval of the government’s handling of the pandemic has been rising, which has translated to the highest government satisfaction that we’ve seen in years. Though approval of the government’s handling of COVID-19 has remained stable, general satisfaction with the federal government has been declining since May. Even so, Trudeau maintains his lead as the best option for Prime Minister of Canada and the Liberals maintain their lead in vote. Today, INNOVATIVE is releasing results from our July 2020 Canada This Month survey. This online survey was in field from July 14th to July 20th with a weighted sample size of 2,000 and oversamples in Alberta and BC. Detailed methodology is provided in the appendix. This report covers key results on how Canadians are rating the Federal government’s handling of COVID-19 and the impacts that is having for government satisfaction and vote choice. 3 Government Approval The federal government continues to receive high marks, both generally and for their handling of COVID-19 specifically. Federal Satisfaction: A majority (54%) report they are satisfied with 4 the performance of the federal government Generally speaking, how satisfied are you with the performance of the FEDERAL government in Canada? Would you -

List of Mps on the Hill Names Political Affiliation Constituency

List of MPs on the Hill Names Political Affiliation Constituency Adam Vaughan Liberal Spadina – Fort York, ON Alaina Lockhart Liberal Fundy Royal, NB Ali Ehsassi Liberal Willowdale, ON Alistair MacGregor NDP Cowichan – Malahat – Langford, BC Anthony Housefather Liberal Mount Royal, BC Arnold Viersen Conservative Peace River – Westlock, AB Bill Casey Liberal Cumberland Colchester, NS Bob Benzen Conservative Calgary Heritage, AB Bob Zimmer Conservative Prince George – Peace River – Northern Rockies, BC Carol Hughes NDP Algoma – Manitoulin – Kapuskasing, ON Cathay Wagantall Conservative Yorkton – Melville, SK Cathy McLeod Conservative Kamloops – Thompson – Cariboo, BC Celina Ceasar-Chavannes Liberal Whitby, ON Cheryl Gallant Conservative Renfrew – Nipissing – Pembroke, ON Chris Bittle Liberal St. Catharines, ON Christine Moore NDP Abitibi – Témiscamingue, QC Dan Ruimy Liberal Pitt Meadows – Maple Ridge, BC Dan Van Kesteren Conservative Chatham-Kent – Leamington, ON Dan Vandal Liberal Saint Boniface – Saint Vital, MB Daniel Blaikie NDP Elmwood – Transcona, MB Darrell Samson Liberal Sackville – Preston – Chezzetcook, NS Darren Fisher Liberal Darthmouth – Cole Harbour, NS David Anderson Conservative Cypress Hills – Grasslands, SK David Christopherson NDP Hamilton Centre, ON David Graham Liberal Laurentides – Labelle, QC David Sweet Conservative Flamborough – Glanbrook, ON David Tilson Conservative Dufferin – Caledon, ON David Yurdiga Conservative Fort McMurray – Cold Lake, AB Deborah Schulte Liberal King – Vaughan, ON Earl Dreeshen Conservative -

The Head Vs. the Heart: in Campaign's 2Nd Week, O

The Head vs. the Heart: In campaign’s 2nd week, O’Toole is voters’ intellectual choice, shares ‘gut’ preference with Singh Trudeau trails on both measures, but all main party leaders chosen by at least ¼ August 26, 2021 – In an election that Suppose you are relying on each... which may be decided by small segments of leader are you most attracted to? (n=1,692) moveable voters migrating between parties, leadership matters. 36% 31% 33% 29% 25% A new study from the non-profit Angus 23% Reid Institute finds that, while the Liberals continue to hang on to a small advantage in vote intent, party chief 8% 6% Justin Trudeau is neither the most 5% 4% attractive leader when voters consider their choice with their head, nor with Heart or gut choice Reason or intellect choice their heart. Erin O’Toole When asked who they would be most Justin Trudeau amenable to if they rely on their gut in this campaign, 23 per cent of Jagmeet Singh Canadians choose Trudeau, compared Yves-François Blanchet (QC Only) to the one-in-three (33%) who pick NDP leader Jagmeet Singh, or the three-in- Annamie Paul ten (31%) who opt for the CPC’s Erin O’Toole. METHODOLOGY: Further, 60 per cent of Liberal The Angus Reid Institute conducted an online survey from Aug. 20- supporters say Trudeau is the most 23, 2021 among a representative randomized sample of 1,692 attractive leader for them if they rely on Canadian adults who are members of Angus Reid Forum. For their gut, while nearly one-third of this comparison purposes only, a probability sample of this size would same base opt for Singh.