Brahminical Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cow Care in Hindu Animal Ethics Kenneth R

THE PALGRAVE MACMILLAN ANIMAL ETHICS SERIES Cow Care in Hindu Animal Ethics Kenneth R. Valpey The Palgrave Macmillan Animal Ethics Series Series Editors Andrew Linzey Oxford Centre for Animal Ethics Oxford, UK Priscilla N. Cohn Pennsylvania State University Villanova, PA, USA Associate Editor Clair Linzey Oxford Centre for Animal Ethics Oxford, UK In recent years, there has been a growing interest in the ethics of our treatment of animals. Philosophers have led the way, and now a range of other scholars have followed from historians to social scientists. From being a marginal issue, animals have become an emerging issue in ethics and in multidisciplinary inquiry. Tis series will explore the challenges that Animal Ethics poses, both conceptually and practically, to traditional understandings of human-animal relations. Specifcally, the Series will: • provide a range of key introductory and advanced texts that map out ethical positions on animals • publish pioneering work written by new, as well as accomplished, scholars; • produce texts from a variety of disciplines that are multidisciplinary in character or have multidisciplinary relevance. More information about this series at http://www.palgrave.com/gp/series/14421 Kenneth R. Valpey Cow Care in Hindu Animal Ethics Kenneth R. Valpey Oxford Centre for Hindu Studies Oxford, UK Te Palgrave Macmillan Animal Ethics Series ISBN 978-3-030-28407-7 ISBN 978-3-030-28408-4 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-28408-4 © Te Editor(s) (if applicable) and Te Author(s) 2020. Tis book is an open access publication. Open Access Tis book is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made. -

The Merchant Castes of a Small Town in Rajasthan

THE MERCHANT CASTES OF A SMALL TOWN IN RAJASTHAN (a study of business organisation and ideology) CHRISTINE MARGARET COTTAM A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Ph.D. at the Department of Anthropology and Soci ology, School of Oriental and African Studies, London University. ProQuest Number: 10672862 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10672862 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 2 ABSTRACT Certain recent studies of South Asian entrepreneurial acti vity have suggested that customary social and cultural const raints have prevented positive response to economic develop ment programmes. Constraints including the conservative mentality of the traditional merchant castes, over-attention to custom, ritual and status and the prevalence of the joint family in management structures have been regarded as the main inhibitors of rational economic behaviour, leading to the conclusion that externally-directed development pro grammes cannot be successful without changes in ideology and behaviour. A focus upon the indigenous concepts of the traditional merchant castes of a market town in Rajasthan and their role in organising business behaviour, suggests that the social and cultural factors inhibiting positivejto a presen ted economic opportunity, stimulated in part by external, public sector agencies, are conversely responsible for the dynamism of private enterprise which attracted the attention of the concerned authorities. -

Delayed Gratification and Parental Decision-Making: Investigating the Impact of Poverty on Child Marriage in India

Delayed Gratification and Parental Decision-Making: Investigating the Impact of Poverty on Child Marriage in India Karan Bains Faculty Advisor: Professor Jessica W. Reyes April 16, 2014 Submitted to the Department of Economics at Amherst College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts with honors. ABSTRACT Child marriage has negative health effects and limits future opportunities available to children, potentially trapping them in a cycle of poverty. While a large body of literature studies the impact of parental decision-making on child welfare in general, this paper applies such thinking to female child marriage in India. I first develop a model of parental decision- making under which poverty constraints lead parents to make suboptimal choices such as marrying their daughters prematurely. I then test this model empirically, estimating a two-stage least squares regression to determine the causal impact of poverty on child marriage. Following Chin and Prakash (2011), I estimate the effect of affirmative action policies on poverty in India. I then use this exogenous variation in poverty to identify the relationship between current poverty and future child marriage outcomes. This analysis is conducted using state-year data for India over the period 1960-2000 from Besley and Burgess (2000), with retrospective child marriage variables constructed from the 2005-06 National Family Health Survey in India. I find that poverty has a significant positive effect on the incidence and depth of child marriage, a result which proves robust to different time periods, data sets, and specifications. More concretely, a one percentage point decrease in current poverty incidence leads to a one percentage point decrease in lifetime child marriage rates. -

We Are Now 3 Issues Old I

Weare now3 issues old I fkxar-iir .?Ole Third Edition December, 2015 With you, By you, For you. TheArtof ENTREPRENEVRSHIP Malaviya National Institute of Technology Jaipur (Institute of National Importance, Established by the Act of Parliament) Jawahar Lal Nehru Marg, Jaipur - 302 017, India (Alumni Magazine of Malaviya National Institute of Technology Jaipur) www.mnit.ac.in PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor Institute Motto CONTENTSDecember 2015 *1T: 4741el:t VISION To create a center for imparting technical education of Messages international standards and conducting research at the cutting edge of technology to meet the current and future challenges of technological development. Alumni Committee (ALCOM) MISSION The Art of Entrepreneurship (Cover Story) To create technical manpower for meeting the current and future demands of industry; to reorganize ALUMNI SECTION education and research in close interaction with industry with emphasis on the development of '89 Batch Reunion leadership qualities in the young men and women entering the portals of the Institute with sensitivity to social development and eye for opportunities for Through my Window growth in the international perspective. Profiles 1970 Batch (1965 Entrance) Between the Lines Design & Print Popular Printers EDITORIAL TEAM Profiles 1990 Batch Jaipur Prof. Dharmendar Boolchandani ^,LAVIYA. r"TIONAL INS1TTUTE CY- TECHNE` Professor Alumni Day 2014 December 2015 Electronics and Communication Engineering Vol - III Developments Prakhar Bansal 4th year, Civil Engineering 10th Convocation Malaviya National Institute of Technology Jaipur Neha Garg (Institute of National Importance, Established by the Act of Parliament) 4th year, Chemical Engineering Jawahar Lal Nehru Marg, MNIT Paathshala Jaipur - 302 017, India www.mnitacin Shruti Trivedi 2nd year, Chemical Engineering Vote of Thanks All rights reserved. -

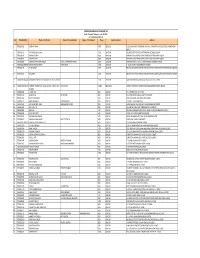

Tax Payers of Barmer District Having Turnover Upto 1.5 Crore

Tax Payers of Barmer District having Turnover upto 1.5 Crore Administrative S.No GSTN_ID TRADE NAME ADDRESS Control 1 CENTRE 08AUJPJ7098Q1ZJ MAHAVEER TRADING COMPANY 200-SHIV MANDIR KE PASS, K-12, KRISHI UPAJ MANDI, BARMER, BARMER, 344001 2 STATE 08APUPP8468G1ZX SARASWATI ENT UDHYOG SHIVKAR, KURLA, BARMER, BARMER, 3 STATE 08AGNPB2451R1ZZ NAVKAR MARKETING HAMIR PURA, BARMER, BARMER, 344001 4 STATE 08GLAPS3519H1ZW MAHADEV FILLING STATION DERPANA, BHUKA BHAGAT SINGH SINDHARI, BARMER, BARMER, 344033 5 STATE 08AIZPK6223E1ZY MANOJ MOTORS CHOHTAN CHORAYA, BARMER, BARMER, BARMER, 344001 6 STATE 08CBCPS3058P1Z0 SIDHI VINAYAK MACHINERY STORE NH 15,SANCHORE ROAD,DHORIMANA, BARMER, BARMER, 7 STATE 08AKUPM3367L2ZA JAI AMBEY CEMENT AGENCY SARKA PAR, KAWAS, TEH.BARMER, BARMER, BARMER, 344001 8 STATE 08APBPS5918K1ZF RAMDEV ENTERPRISES STATION ROAD, BARMER, BARMER, BARMER, 344001 9 STATE 08AQAPD1285G1Z6 PALIWAL MOTORS NH-15, PALIWAL MARKET, OPP. KRASHI MANDI,NH-15, BARMER, BARMER, 344001 10 STATE 08ASFPS2843E1ZO MAHALAXMI CEMENT AGENCY CHOHTAN, TEH.CHOHTAN, BARMER, BARMER, 11 CENTRE 08ASXPR1331G1ZE JAMBHESHWAR ENTERPRISES NH - 15DHORIMANA, BARMER, BARMER, 12 STATE 08AAWPJ8789P1Z5 CHINTAMANI DAS AMRIT LAL I-26, KRISHI UPAJ MANDI, BARMER, BARMER, 13 STATE 08AITPR5394P1ZW RADHEY KRISHAN STONE CRUSHING COMPANY LUNU KHURAD, BARMER, BARMER, 344001 14 STATE 08AAVPD5725E1ZL KAPIL AGENCY NAYAPURA, BARMER, BARMER, 344001 15 STATE 08AIAPV1445J1Z3 SHIVAM HP GAS GRAMIN VITARAK SHOBHALA DARSHAN, SONADI, BARMER, BARMER, 344001 16 STATE 08ABBPM6195J1Z9 ASHOK M. MEHTA LAXMI BAZAR, BARMER, BARMER, BARMER, 17 STATE 08ALJPR3888H1ZE KHILJEE INDUSTRIES H1 BY 37, RIICO INDUSTRIAL AREA, BARMER, BARMER, 344001 18 STATE 08BBWPK2773A1ZG CHAMUNDA ENTERPRISES BHATALA, TEH. SINDARI, BARMER, BARMER, 344001 19 STATE 08BPTPS9842F1Z0 SHREE VIRATRA TYRES NH-15 SANCHORE ROAD, DHORIMANA, BARMER, BARMER, 20 STATE 08AFCPD9643P1ZY NANURAM MANGILAL LAXMI BAZAR, BARMER, BARMER, BARMER, 21 CENTRE 08AYBPR8618Q1ZJ SODHA H. -

A.W. Entwistle Braj Centre of Krishna Pilgrimage Egbert Forsten

A.W. Entwistle Braj Centre of Krishna Pilgrimage Egbert Forsten. Groningen. 1987. file:///W|/Resources/AA/00/00/03/01/00001/00002.txt[21/11/2016 07:19:08] This book has been written and published with financial support from the Netherlands Organization for the Advancement of Pure Research (Z.W.O.) Cover illustration & frontispiece: The temple of Shrinathji on the Govard- han hill as seen from Anyor Cover design: Jurjen Pinkster Distributor for India and the Indian Subcontinent: Motilal Banarsidass, Bungalow Road, Jawahar Nagar, Dehli 110 007 (India). CIP-GEGEVENS KONINKLIJKE BIBLIOTHEEK, DEN HAAG Entwistle, Alan W. Braj, Centre of Krishna Pilgrimage / Alen W. Entwistle. Groningen : Forsten. Ill., krt. (Groningen Oriental Studies ; vol. 3) Met 3 kaarten. Met lit. opg., reg. isbn 90-6980-016-0 geb. siso 214.4 UDC 294-5 (54) (091) Trefw. : Braj (India); cultuurgeschiedenis / Krishna-cultus ; bedevaart; India. Copyright 1987, Egbert Forsten, Groningen, The Netherlands All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. file:///W|/Resources/AA/00/00/03/01/00001/00003.txt[21/11/2016 07:19:08] Contents Abbreviations vii Preface ix 1 Introduction 1 The landscape 1 2 The local inhabitants 4 3 The devotional sects 8 4 Varieties of pilgrimage 12 5 Rules and regulations 19 2 The myth 1 The scriptural sources 22 2 The setting 27 3 The birth of -

The Politics of Representation

The Politics of Representation Enumeration and the Mobilization of Caste Identity in Colonial India c. 1900-1935 ICLS Senior Thesis April 12, 2012 1 The Politics of Representation: Enumeration and the Mobilization of Caste Identity in Colonial India c. 1900-1935 Contents Abstract ………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Part I : Representations of Caste A brief history ……………………………………………………………………………… 2 Part II : Governance, ethnography, identity Numbers and the colonial state: an “administrative episteme” …………………………… 19 The genealogy of caste enumeration: gazetteers and early censuses, 1857-1901 ………… 20 Systematizing social divisions: H.H. Risley and the Census of 1901 …………………… 25 Mobility and the limits of caste contestation: The census and the formation of the non-Brahmin public sphere in Bombay …………………………………………… 30 Part III : Mobilizing minority: statistics, politics, and the Dalit challenge Colonial governmentality and its interlocutors …………………………………………. 36 A shifting tide: the dilemmas of the last caste censuses, 1921-1931 ……………………. 39 The Dalit case: diagnosis and prescriptions …………………………………………… 44 Ambedkar as Dalit representative ……………………………………………… 49 Secularizing untouchability …………………………………………………………… 54 Conclusions …………………………………………………………………………………… 58 Works Cited …………………………………………………………………………………… 61 2 Abstract Ever since the publication of Bernard Cohn’s “The Census, Social Structure, and Objectification in South Asia” in 1987, the caste census has become an important node of scholarship on the relationship between knowledge production and social structure in colonial India. Much of this scholarship falls within an anti- or post-colonial framework, emphasizing the ways in which the caste census, as a tool of colonial knowledge-power production, participated in producing the modern “caste system,” while leaving out the ways in which such statistical tools as the census were put to use by the most marginalized caste groups in the service of emancipation. -

Cultural Proximity and Loan Outcomes

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES CULTURAL PROXIMITY AND LOAN OUTCOMES Raymond Fisman Daniel Paravisini Vikrant Vig Working Paper 18096 http://www.nber.org/papers/w18096 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 May 2012 Thanks to Andres Lieberman and Sravya Mamadiana for outstanding research assistance. We would like to thank Abhijit Banerjee, Oriana Bandiera, Shawn Cole, Esther Duflo, Michael Kremer, Raghu Rajan, Antoinette Schoar, Paola Sapienza, Luigi Zingales, and the participants at the CFS-EIEF Conference on Household Finance, Columbia University, Boston University, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, London Business School, London School of Economics - Development, MIT-Sloan, the NBER conferences in corporate finance and household finance, Stockholm School of Economics, and Vienna University of Economics and Business for valuable feedback. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2012 by Raymond Fisman, Daniel Paravisini, and Vikrant Vig. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Cultural Proximity and Loan Outcomes Raymond Fisman, Daniel Paravisini, and Vikrant Vig NBER Working Paper No. 18096 May 2012 JEL No. D82,G21,J15 ABSTRACT We present evidence that shared codes, religious beliefs, ethnicity - cultural proximity - between lenders and borrowers improves the efficiency of credit allocation. -

List of Shareholders Whose Final Dividend

TORRENTPHARMACEUTICALSLIMITED Details of Unpaid Dividend as on 01.09.2018 for Final Dividend 2017‐18 Sno Folio/DpidClid Name o f the Holder Name of Second Holder Name of Third Holder Shares Amount Due (Rs.) Address 1 TRE0026719 VIDEHA R SHAH 5600 28000.00 D 502, DHANANJAY TOWER,NR. SHYAMAL CHAR RASTA,SATELLITE ROAD,AHMEDABAD‐ 380015 2 TRE0026716 HASMUKHLAL M SHAH 5600 28000.00 18 LAD SOCIETY OUTSIDE VASTRAPURAHMEDABAD‐380054 3 TRE0036281 HARSHAD DESAI 8000 40000.00 SANJIVANI BLDG PHEROZSHAH STSANTACRUZ WBOMBAY‐400054 4 TRE0038073 PUSHPA DESAI 8000 40000.00 SANJIVANI BLDG PHEROZSHAH STSANTACRUZ WBOMBAY‐400054 5 TRE0005089 KANAYO DWARKADAS AHUJA GOPAL DWARKADAS AHUJA 2400 12000.00 DYNA HOUSE A‐57 STREET 1 MIDC ANDHERI EBOMBAY‐400093 6 IN30018312968815 RAJESH PRASAD MISRA MAYA MISRA 2400 12000.00 E ‐1/ 183 ARERA COLONYBHOPAL‐462016 7 TRE0031464 P VENKATESH 2400 12000.00 SRIVARU SECURITIES PRIVATE LIMITED49 THATHA MUTHIAPPAN STREETMADRAS‐600001 8 TRE0031465 D GANESH 2400 12000.00 SRIVARU SECURITIES PRIVATE LIMITED49 THATHA MUTHIAPPAN STREETMADRAS‐600001 9 IN30045010084885 KOOMBER PROPERTIES & LEASING COMPANY LIMITED 2200 11000.00 CAMELLIA HOUSE14, GURUSADAY ROADCALCUTTA‐700019 10 IN30039418405533 TORRENT PHARMACEUTICALS LIMITED ‐ UNCLAIMED SE ACCOUNT 57880 289400.00 TORRENT HOUSEOFF ASHRAM ROADAHMEDABADGUJARAT‐380009 SUSPEN 11 TRE0010943 J K RATHOD 800 4000.00 R F O ATPOST KASA D THANE0 12 TRE0012716 JAGDISH LAL RAJ KUMAR 800 4000.00 42 A EKTA VIHAR AMBALA CANTTHARYANA0 13 TRE0012833 BALVINDER SINGH 400 2000.00 H NO 1365/3 MIG FLAT PHASE‐XI -

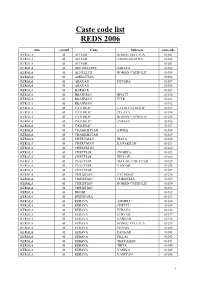

Caste Code List REDS 2006

Caste code list REDS 2006 state stateid Caste Subcaste castecode KERALA 01 ACHARI KONGU VELLALA 01001 KERALA 01 ACHARI VISHWAKARMA 01002 KERALA 01 ACHARI 01003 KERALA 01 ADI DRAVIDA PARAYA 01004 KERALA 01 AENTELUR ROMAN CATHOLIC 01005 KERALA 01 AMBATTAN 01006 KERALA 01 ARAYAN DEVARA 01007 KERALA 01 ARAYAN 01008 KERALA 01 BARBAR 01009 KERALA 01 BRAHMAN BHATT 01010 KERALA 01 BRAHMAN IYER 01011 KERALA 01 BRAHMAN 01012 KERALA 01 CATHOLIC LATIN CATHOLIC 01013 KERALA 01 CATHOLIC PULAYA 01014 KERALA 01 CATHOLIC ROMAN CATHOLIC 01015 KERALA 01 CATHOLIC SYRIAN 01016 KERALA 01 CATHOLIC 01017 KERALA 01 CHAKKILIYAN AMMA 01018 KERALA 01 CHAKKILIYAN 01019 KERALA 01 CHERUMAN IRAYA 01020 KERALA 01 CHERUMAN KANAKKAN 01021 KERALA 01 CHERUMAN 01022 KERALA 01 CHETTIAR CHAKKA 01023 KERALA 01 CHETTIAR TELUGU 01024 KERALA 01 CHETTIAR TELUGU CHETTIAR 01025 KERALA 01 CHETTIAR VANIAR 01026 KERALA 01 CHETTIAR 01027 KERALA 01 CHRISTIAN CATHOLIC 01028 KERALA 01 CHRISTIAN CHRISTIAN 01029 KERALA 01 CHRISTIAN ROMAN CATHOLIC 01030 KERALA 01 CHRISTIAN 01031 KERALA 01 DHOBI 01032 KERALA 01 DWEEPARA 01033 KERALA 01 EZHAVA AMMELU 01034 KERALA 01 EZHAVA CHETTI 01035 KERALA 01 EZHAVA EZHAVA 01036 KERALA 01 EZHAVA GHIYAIU 01037 KERALA 01 EZHAVA HARIJAN 01038 KERALA 01 EZHAVA KONGU VELLALA 01039 KERALA 01 EZHAVA MENON 01040 KERALA 01 EZHAVA PANKAR 01041 KERALA 01 EZHAVA PILLAI 01042 KERALA 01 EZHAVA THEYAHAN 01043 KERALA 01 EZHAVA THIYA 01044 KERALA 01 EZHAVA VANIKA 01045 KERALA 01 EZHAVA VANIYAN 01046 1 state stateid Caste Subcaste castecode KERALA 01 EZHAVA VARRER 01047 KERALA 01 EZHAVA VATHI 01048 KERALA 01 EZHAVA 01049 KERALA 01 EZHUTHACHAN 01050 KERALA 01 G.S.B. -

Dr. R.K. Maheshwari

Dr. R.K. Maheshwari 1. Personal Information (i) Name Rajesh Kumar Maheshwari Photo (ii) Qualification Ph.D. (iii) Designation Professor (iv) Email-id [email protected] (v) Employee No. (Vi) Department Department of Pharmacy S.G.S.I.T.S. Indore (vii) Experience • Post-Graduation Classes- 31 Years. • Under Graduation Classes- 33 Years. • Served M/s Martand Pharmaceuticals, Baraut (U.P.) as manufacturing chemist for 2 years and 8 months (12th Jan 1983 to 27th Sep 1985) and got approvals as manufacturing chemist for injectables, liquids (oral), tablets, capsules and ointments. 2. Educational Qualification S. No. Degree Specialization Year University/Board 1. Higher - 1975 Board of secondary Education Secondary M.P. Board, Bhopal 2. B.Pharm. - 1979 Dr. H.S.Gour University, Sagar (MP) 3. M.Pharm. Pharmaceutics 1981 Dr. H.S.Gour University, Sagar (MP) 4. Ph.D. Pharmaceutics 2008 School of Pharmacy, DAVV, Indore (MP) 3. Research Interests Solubilization, eco-friendly methods in analysis and formulation. 4. Research Paper Publications (I) International/National Journal Publications 1 R.K. Maheshwari, ‘Analysis of frusemide by application of hydrotropic solubilization phenomenon,’ The Indian Pharmacist, Vol. IV, No. 34, April 2005, p. 55-58. (Details-Titrimetric estimation, Hydrotropic solution- 2 M Sodium benzoate). 2 R. K. Maheshwari, “Spectrophotometric determination of cefixime in tablets by hydrotropic solubilization phenomenon,” The Indian Pharmacist, Vol. IV, No. 36, June 2005, p. 63-68. (Details-Spectrophotometric estimation at 288 nm, Hydrotropic solutions- 8 M Urea, 4 M Sodium acetate and 1.25 M Sodium citrate). 3 R. K. Maheshwari, S. C. Chaturvedi & N.K. Jain, “Application of hydrotropic solubilization phenomenon in spectrophotometric analysis of hydrochlorothiazide tablets,” Indian Drugs, 42(8), August 2005, p.