A.W. Entwistle Braj Centre of Krishna Pilgrimage Egbert Forsten

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Epic Imagination in Contemporary Indian Literature

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School May 2017 Modern Mythologies: The picE Imagination in Contemporary Indian Literature Sucheta Kanjilal University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the South and Southeast Asian Languages and Societies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Kanjilal, Sucheta, "Modern Mythologies: The pE ic Imagination in Contemporary Indian Literature" (2017). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/6875 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Modern Mythologies: The Epic Imagination in Contemporary Indian Literature by Sucheta Kanjilal A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy with a concentration in Literature Department of English College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Gurleen Grewal, Ph.D. Gil Ben-Herut, Ph.D. Hunt Hawkins, Ph.D. Quynh Nhu Le, Ph.D. Date of Approval: May 4, 2017 Keywords: South Asian Literature, Epic, Gender, Hinduism Copyright © 2017, Sucheta Kanjilal DEDICATION To my mother: for pencils, erasers, and courage. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS When I was growing up in New Delhi, India in the late 1980s and the early 1990s, my father was writing an English language rock-opera based on the Mahabharata called Jaya, which would be staged in 1997. An upper-middle-class Bengali Brahmin with an English-language based education, my father was as influenced by the mythological tales narrated to him by his grandmother as he was by the musicals of Broadway impressario Andrew Lloyd Webber. -

In the Name of Krishna: the Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town

In the Name of Krishna: The Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Sugata Ray IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Frederick M. Asher, Advisor April 2012 © Sugata Ray 2012 Acknowledgements They say writing a dissertation is a lonely and arduous task. But, I am fortunate to have found friends, colleagues, and mentors who have inspired me to make this laborious task far from arduous. It was Frederick M. Asher, my advisor, who inspired me to turn to places where art historians do not usually venture. The temple city of Khajuraho is not just the exquisite 11th-century temples at the site. Rather, the 11th-century temples are part of a larger visuality that extends to contemporary civic monuments in the city center, Rick suggested in the first class that I took with him. I learnt to move across time and space. To understand modern Vrindavan, one would have to look at its Mughal past; to understand temple architecture, one would have to look for rebellions in the colonial archive. Catherine B. Asher gave me the gift of the Mughal world – a world that I only barely knew before I met her. Today, I speak of the Islamicate world of colonial Vrindavan. Cathy walked me through Mughal mosques, tombs, and gardens on many cold wintry days in Minneapolis and on a hot summer day in Sasaram, Bihar. The Islamicate Krishna in my dissertation thus came into being. -

Bhagavata Purana

Bhagavata Purana The Bh āgavata Pur āṇa (Devanagari : भागवतपुराण ; also Śrīmad Bh āgavata Mah ā Pur āṇa, Śrīmad Bh āgavatam or Bh āgavata ) is one of Hinduism 's eighteen great Puranas (Mahapuranas , great histories).[1][2] Composed in Sanskrit and available in almost all Indian languages,[3] it promotes bhakti (devotion) to Krishna [4][5][6] integrating themes from the Advaita (monism) philosophy of Adi Shankara .[5][7][8] The Bhagavata Purana , like other puranas, discusses a wide range of topics including cosmology, genealogy, geography, mythology, legend, music, dance, yoga and culture.[5][9] As it begins, the forces of evil have won a war between the benevolent devas (deities) and evil asuras (demons) and now rule the universe. Truth re-emerges as Krishna, (called " Hari " and " Vasudeva " in the text) – first makes peace with the demons, understands them and then creatively defeats them, bringing back hope, justice, freedom and good – a cyclic theme that appears in many legends.[10] The Bhagavata Purana is a revered text in Vaishnavism , a Hindu tradition that reveres Vishnu.[11] The text presents a form of religion ( dharma ) that competes with that of the Vedas , wherein bhakti ultimately leads to self-knowledge, liberation ( moksha ) and bliss.[12] However the Bhagavata Purana asserts that the inner nature and outer form of Krishna is identical to the Vedas and that this is what rescues the world from the forces of evil.[13] An oft-quoted verse is used by some Krishna sects to assert that the text itself is Krishna in literary -

Vidura, Uddhava and Maitreya

Çré Çayana Ekädaçé Issue no: 17 27th July 2015 Vidura, Uddhava and Maitreya Features VIDURA QUESTIONS UDDHAVA Srila Sukadeva Goswami THE MOST EXALTED PERSONALITY IN THE VRISHNI DYNASTY Lord Krishna instructing Uddhava Lord Sriman Purnaprajna Dasa UDDHAVA REMEMBERS KRISHNA Srila Vishvanatha Chakravarti Thakur UDDHAVA GUIDES VIDURA TO TAKE SHELTER OF MAITREYA ÅñI Srila Sukadeva Goswami WHY DID UDDHAVA REFUSE TO BECOME THE SPIRITUAL MASTER OF VIDURA? His Divine Grace A .C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada WHY DID KRISHNA SEND UDDHAVA TO BADRIKASHRAMA? Srila Vishvanatha Chakravarti Thakur WHO IS MAITREYA ÅñI? Srila Krishna-Dvaipayana Vyasa Issue no 16, Page — 2 nityaà bhägavata-sevayä VIDURA QUESTIONS UDDHAVA be the cause of the Åg Veda, the creator of the mind Srila Sukadeva Goswami and the fourth Plenary expansion of Viñëu. O sober one, others, such as Hridika, Charudeshna, Gada and After passing through very wealthy provinces like the son of Satyabhama, who accept Lord Sri Krishna Surat, Sauvira and Matsya and through western India, as the soul of the self and thus follow His path without known as Kurujangala. At last he reached the bank of deviation-are they well? Also let me inquire whether the Yamuna, where he happened to meet Uddhava, Maharaja Yudhisthira is now maintaining the kingdom the great devotee of Lord Krishna. Then, due to his great according to religious principles and with respect love and feeling, Vidura embraced him [Uddhava], for the path of religion. Formerly Duryodhana was who was a constant companion of Lord Krishna and burning with envy because Yudhisthira was being formerly a great student of Brihaspati's. -

Mahabharata Tatparnirnaya

Mahabharatha Tatparya Nirnaya Chapter XIX The episodes of Lakshagriha, Bhimasena's marriage with Hidimba, Killing Bakasura, Draupadi svayamwara, Pandavas settling down in Indraprastha are described in this chapter. The details of these episodes are well-known. Therefore the special points of religious and moral conduct highlights in Tatparya Nirnaya and its commentaries will be briefly stated here. Kanika's wrong advice to Duryodhana This chapter starts with instructions of Kanika an expert in the evil policies of politics to Duryodhana. This Kanika was also known as Kalinga. Probably he hailed from Kalinga region. He was a person if Bharadvaja gotra and an adviser to Shatrujna the king of Sauvira. He told Duryodhana that when the close relatives like brothers, parents, teachers, and friends are our enemies, we should talk sweet outwardly and plan for destroying them. Heretics, robbers, theives and poor persons should be employed to kill them by poison. Outwardly we should pretend to be religiously.Rituals, sacrifices etc should be performed. Taking people into confidence by these means we should hit our enemy when the time is ripe. In this way Kanika secretly advised Duryodhana to plan against Pandavas. Duryodhana approached his father Dhritarashtra and appealed to him to send out Pandavas to some other place. Initially Dhritarashtra said Pandavas are also my sons, they are well behaved, brave, they will add to the wealth and the reputation of our kingdom, and therefore, it is not proper to send them out. However, Duryodhana insisted that they should be sent out. He said he has mastered one hundred and thirty powerful hymns that will protect him from the enemies. -

Download Book

PREMA-SAGARA OR OCEAN OF LOVE THE PREMA-SAGARA OR OCEAN OF LOVE BEING A LITERAL TRANSLATION OF THE HINDI TEXT OF LALLU LAL KAVI AS EDITED BY THE LATE PROCESSOR EASTWICK, FULLY ANNOTATED AND EXPLAINED GRAMMATICALLY, IDIOMATICALLY AND EXEGETICALLY BY FREDERIC PINCOTT (MEMBER OF THE ROYAL ASIATIC SOCIETY), AUTHOR OF THE HINDI ^NUAL, TH^AKUNTALA IN HINDI, TRANSLATOR OF THE (SANSKRIT HITOPADES'A, ETC., ETC. WESTMINSTER ARCHIBALD CONSTABLE & CO. S.W. 2, WHITEHALL GARDENS, 1897 LONDON : PRINTED BY GILBERT AND KIVJNGTON, LD-, ST. JOHN'S HOUSE, CLEKKENWELL ROAD, E.G. TRANSLATOR'S PREFACE IT is well known to aU who have given thought to the languages of India that the or Bhasha as Hindi, the people themselves call is the most diffused and most it, widely important language of India. There of the are, course, great provincial languages the Bengali, Marathi, Panjabi, Gujarat!, Telugu, and Tamil which are immense numbers of spoken by people, and a knowledge of which is essential to those whose lot is cast in the districts where are but the Bhasha of northern India towers they spoken ; high above them both on account of the all, number of its speakers and the important administrative and commercial interests which of attach to the vast stretch territory in which it is the current form of speech. The various forms of this great Bhasha con- of about stitute the mother-tongue eighty-six millions of people, a almost as as those of the that is, population great French and German combined and cover the empires ; they important region hills on the east to stretching from the Rajmahal Sindh on the west and from Kashmir on the north to the borders of the ; the south. -

1002 a K Int Coll Karab Mathura B 1003 Adarsh Int Coll Mitthauli Mathura B

PAGE:- 1 BHS&IE, UP EXAM YEAR-2021 *** PROPOSED CENTRE ALLOTMENT REPORT (UPDATED BY DISTRICT COMMITTEE) *** DIST-CD & NAME:- 05 MATHURA DATE:- 13/02/2021 CENT-CODE & NAME CENT-STATUS CEN-REMARKS EXAM SCH-STATUS SCHOOL CODE & NAME #SCHOOL-ALLOT SEX PART GROUP 1002 A K INT COLL KARAB MATHURA B HIGH BRM 1002 A K INT COLL KARAB MATHURA 46 F HIGH BRM 1022 S K D A INTER COLLEGE PACHAWAR MATHURA 7 M HIGH CRM 1123 D B R A I C ALIPUR KHERIYA MATHURA 7 F HIGH CRM 1212 SRI SS RATNI DEVI IC SIHORA MATHURA 36 F HIGH CRM 1213 SRI BABU KHAN H S ITAULI MATHURA 13 F HIGH CRM 1213 SRI BABU KHAN H S ITAULI MATHURA 44 M HIGH CRM 1237 B KHACHER SINGH I C BANDI MATHURA 11 F HIGH CRM 1344 M B S INTER COLLEGE NAGLA TEJA SIHORA MATHURA 109 M HIGH CUM 1432 PT HARI SHANKAR DWIVEDI HSS PURANA BUS STAND BALDEO MATHURA 55 M 328 INTER BRM 1002 A K INT COLL KARAB MATHURA 47 F ALL GROUP INTER BRM 1022 S K D A INTER COLLEGE PACHAWAR MATHURA 3 M OTHER THAN SCICNCE INTER CRM 1143 SHRI SHER SINGH M A I C CHHAULI MATHURA 23 M SCIENCE INTER CRM 1212 SRI SS RATNI DEVI IC SIHORA MATHURA 45 F SCIENCE INTER CRM 1344 M B S INTER COLLEGE NAGLA TEJA SIHORA MATHURA 185 M SCIENCE 303 CENTRE TOTAL >>>>>> 631 1003 ADARSH INT COLL MITTHAULI MATHURA B HIGH BRM 1003 ADARSH INT COLL MITTHAULI MATHURA 26 F HIGH BRM 1009 BRIJ HITKARI INT COLL BAJNA MATHURA 45 M HIGH BRM 1036 S K V INT COLL MANAGARHI MATHURA 16 F HIGH CUM 1190 S B B INTER COLLEGE BAJNA MATHURA 62 M HIGH CRM 1378 BALAJI H S SCHOOL MANIGARHI MATHURA 36 M HIGH CRM 1393 S H B INTER COLLEGE MUSMUNA MATHURA 67 M HIGH CRM 1465 BABA -

Journal of Bengali Studies

ISSN 2277-9426 Journal of Bengali Studies Vol. 6 No. 1 The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century Dolpurnima 16 Phalgun 1424 1 March 2018 1 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426), Vol. 6 No. 1 Published on the Occasion of Dolpurnima, 16 Phalgun 1424 The Theme of this issue is The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century 2 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 ISSN 2277-9426 Journal of Bengali Studies Volume 6 Number 1 Dolpurnima 16 Phalgun 1424 1 March 2018 Spring Issue The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century Editorial Board: Tamal Dasgupta (Editor-in-Chief) Amit Shankar Saha (Editor) Mousumi Biswas Dasgupta (Editor) Sayantan Thakur (Editor) 3 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 Copyrights © Individual Contributors, while the Journal of Bengali Studies holds the publishing right for re-publishing the contents of the journal in future in any format, as per our terms and conditions and submission guidelines. Editorial©Tamal Dasgupta. Cover design©Tamal Dasgupta. Further, Journal of Bengali Studies is an open access, free for all e-journal and we promise to go by an Open Access Policy for readers, students, researchers and organizations as long as it remains for non-commercial purpose. However, any act of reproduction or redistribution (in any format) of this journal, or any part thereof, for commercial purpose and/or paid subscription must accompany prior written permission from the Editor, Journal of Bengali Studies. -

Judicial System in India During Mughal Period with Special Reference to Persian Sources

Judicial System in India during Mughal Period with Special Reference to Persian Sources (Nezam-e-dadgahi-e-Hend der ahd-e-Gorkanian bewizha-e manabe-e farsi) For the Award ofthe Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Submitted by Md. Sadique Hussain Under the Supervision of Dr. Akhlaque Ahmad Ansari Center Qf Persian and Central Asian Studies, School of Language, Literature and Culture Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi -110067. 2009 Center of Persian and Central Asian Studies, School of Language, Literature and Culture Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi -110067. Declaration Dated: 24th August, 2009 I declare that the work done in this thesis entitled "Judicial System in India during Mughal Period with special reference to Persian sources", for the award of degree of Doctor of Philosophy, submitted by me is an original research work and has not been previously submitted for any other university\Institution. Md.Sadique Hussain (Name of the Scholar) Dr.Akhlaque Ahmad Ansari (Supervisor) ~1 C"" ~... ". ~- : u- ...... ~· c "" ~·~·.:. Profess/~ar Mahdi 4 r:< ... ~::.. •• ~ ~ ~ :·f3{"~ (Chairperson) L~.·.~ . '" · \..:'lL•::;r,;:l'/ [' ft. ~ :;r ':1 ' . ; • " - .-.J / ~ ·. ; • : f • • ~-: I .:~ • ,. '· Attributed To My Parents INDEX Acknowledgment Introduction 1-7 Chapter-I 8-60 Chapter-2 61-88 Chapter-3 89-131 Chapter-4 132-157 Chapter-S 158-167 Chapter-6 168-267 Chapter-? 268-284 Chapter-& 285-287 Chapter-9 288-304 Chapter-10 305-308 Conclusion 309-314 Bibliography 315-320 Appendix 321-332 Acknowledgement At first I would like to praise God Almighty for making the tough situations and conditions easy and favorable to me and thus enabling me to write and complete my Ph.D Thesis work. -

Development of Iconic Tourism Sites in India

Braj Development Plan for Braj Region of Uttar Pradesh - Inception Report (May 2019) INCEPTION REPORT May 2019 PREPARATION OF BRAJ DEVELOPMENT PLAN FOR BRAJ REGION UTTAR PRADESH Prepared for: Uttar Pradesh Braj Tirth Vikas Parishad, Uttar Pradesh Prepared By: Design Associates Inc. EcoUrbs Consultants PVT. LTD Design Associates Inc.| Ecourbs Consultants| Page | 1 Braj Development Plan for Braj Region of Uttar Pradesh - Inception Report (May 2019) DISCLAIMER This document has been prepared by Design Associates Inc. and Ecourbs Consultants for the internal consumption and use of Uttar Pradesh Braj Teerth Vikas Parishad and related government bodies and for discussion with internal and external audiences. This document has been prepared based on public domain sources, secondary & primary research, stakeholder interactions and internal database of the Consultants. It is, however, to be noted that this report has been prepared by Consultants in best faith, with assumptions and estimates considered to be appropriate and reasonable but cannot be guaranteed. There might be inadvertent omissions/errors/aberrations owing to situations and conditions out of the control of the Consultants. Further, the report has been prepared on a best-effort basis, based on inputs considered appropriate as of the mentioned date of the report. Consultants do not take any responsibility for the correctness of the data, analysis & recommendations made in the report. Neither this document nor any of its contents can be used for any purpose other than stated above, without the prior written consent from Uttar Pradesh Braj Teerth Vikas Parishadand the Consultants. Design Associates Inc.| Ecourbs Consultants| Page | 2 Braj Development Plan for Braj Region of Uttar Pradesh - Inception Report (May 2019) TABLE OF CONTENTS DISCLAIMER ......................................................................................................................................... -

The Calendars of India

The Calendars of India By Vinod K. Mishra, Ph.D. 1 Preface. 4 1. Introduction 5 2. Basic Astronomy behind the Calendars 8 2.1 Different Kinds of Days 8 2.2 Different Kinds of Months 9 2.2.1 Synodic Month 9 2.2.2 Sidereal Month 11 2.2.3 Anomalistic Month 12 2.2.4 Draconic Month 13 2.2.5 Tropical Month 15 2.2.6 Other Lunar Periodicities 15 2.3 Different Kinds of Years 16 2.3.1 Lunar Year 17 2.3.2 Tropical Year 18 2.3.3 Siderial Year 19 2.3.4 Anomalistic Year 19 2.4 Precession of Equinoxes 19 2.5 Nutation 21 2.6 Planetary Motions 22 3. Types of Calendars 22 3.1 Lunar Calendar: Structure 23 3.2 Lunar Calendar: Example 24 3.3 Solar Calendar: Structure 26 3.4 Solar Calendar: Examples 27 3.4.1 Julian Calendar 27 3.4.2 Gregorian Calendar 28 3.4.3 Pre-Islamic Egyptian Calendar 30 3.4.4 Iranian Calendar 31 3.5 Lunisolar calendars: Structure 32 3.5.1 Method of Cycles 32 3.5.2 Improvements over Metonic Cycle 34 3.5.3 A Mathematical Model for Intercalation 34 3.5.3 Intercalation in India 35 3.6 Lunisolar Calendars: Examples 36 3.6.1 Chinese Lunisolar Year 36 3.6.2 Pre-Christian Greek Lunisolar Year 37 3.6.3 Jewish Lunisolar Year 38 3.7 Non-Astronomical Calendars 38 4. Indian Calendars 42 4.1 Traditional (Siderial Solar) 42 4.2 National Reformed (Tropical Solar) 49 4.3 The Nānakshāhī Calendar (Tropical Solar) 51 4.5 Traditional Lunisolar Year 52 4.5 Traditional Lunisolar Year (vaisnava) 58 5. -

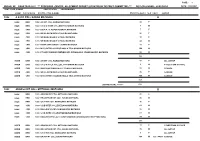

Mewar Residency, Rajputana Gazetteers

MEWAR RESIDENCY, RAJPUTANA GAZETTEERS. VOLUME II.~~ THE MEWAR RESIDENCY . .__.,... • .--, 0 STATISTICAL TABLES. COMPILED BY MAJOR K. D. ERSKINE, I.A. ~C~~ ~- • AJMER: SCOTTISH MISSION INDUSTRIES CO.,- LTD. 1908. CONTENTS. THE MEWAR RESIDENCY. PAGE. TABLE No. I.-Area, populati<;m, and normal khc7lsa reYenue ·of the four States '' 1 .. 2.~List of Political Agents and Residents 2-3 UDAIPUR STATE. TABLE. No. a.-Temperature at Udaipur city since 1898 4 ,. 4.-Rainfa.ll , , , 1896, with average for twenty-six years ending 1905 5 4A.-Rainfall at KherWii.ra cantonment ditto ditto 6 " 4B.- , ., Kotra ditto ditto ditto .. 7 " 5.-List of chiefs of .Mewli.r ... 8-12 " 6. -Population at the three enumerations 13 " .. 7.- , in 1901 by districts eto. 14: , 8.-Average monthly wages of skilled and unskilled labour 15 9. -Average prices of certain food grains and salt 16 " , ·10.-The Udaipur-Chitor Railway 17 11. -List of roads 18 " 12.- , , Imperial post and telegraph offices ... 19 " 13.-The Central Jail at Udaipur city .... " 20 H.-Education in 1905-06 21 " , 15.-List of schools in 1906 -~ 2'2-24 16.-Medical institutions 25 " 17.-List of hospitals and dispensaries in 1905 . 26 " ... , lR.-Vaccination 27 , 19.-List of nobles of the first rank •.• 28-29 DuNGARl'UR STATE. TABLE No. 20. -Rainfall at Diingarpur town since 1899, with average for seven years ending 1905 30 " 21.- List of chiefs of the Bagar and Diingarpur ... •;.• ... 31·32 11 PAGE. r.ABLE No. 22.-Population at the three enumera~ions 33 , . 23.- , . in 1901 by districts 34 , 24.-.Agricultural statistics 35 , 25.-Average prices of certain food grains and pulses and salt at Diingarpur town 36 , 26.-List of nobles of the first class 37 " 27.-The Jail at Diingarpur town 38 , 28.-List of schools in 1905-06 39 , 29.-Medical institutions and vaccination 40 BANSWARA STATE.