The Politics of Representation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

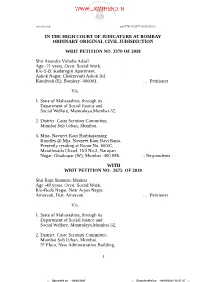

IN the HIGH COURT of JUDICATURE at BOMBAY ORDINARY ORIGINAL CIVIL JURISDICTION WRIT PETITION NO. 3370 of 2018 Shri Anandra Vitho

spb/vai/ppn/bdp wp3370-18-2675-9426-20.doc IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUDICATURE AT BOMBAY ORDINARY ORIGINAL CIVIL JURISDICTION WRIT PETITION NO. 3370 OF 2018 Shri Anandra Vithoba Adsul Age -71 years, Occu: Social Work, R/o-5-B, Kadamgiri Apartment, Ashok Nagar, Chakravarti Ashok Rd, Kandivali (E), Bombay- 400001. … Petitioner V/s. 1. State of Maharashtra, through its Department of Social Justice and Social Welfare, Mantralaya,Mumbai-32. 2. District Caste Scrutiny Committee, Mumbai Sub Urban, Mumbai. 3. Miss. Navneet Kaur Harbhajansing Kundles @ Mrs. Navneet Kaur Ravi Rana, Presently residing at Room No. 600/C, Marathwada Chawl, Hill No.2, Narayan Nagar, Ghatkopar (W), Mumbai -400 086. ... Respondents WITH WRIT PETITION NO. 2675 OF 2019 Shri Raju Shamrao Mankar Age -49 years, Occu: Social Work, R/o-Boda Nagar, Near Arjun Nagar, Amravati, Dist. Amravati. … Petitioner V/s. 1. State of Maharashtra, through its Department of Social Justice and Social Welfare, Mantralaya,Mumbai-32. 2. District Caste Scrutiny Committee, Mumbai Sub Urban, Mumbai. th 5 Floor, New Administrative Building, 1 ::: Uploaded on - 08/06/2021 ::: Downloaded on - 08/06/2021 13:37:37 ::: spb/vai/ppn/bdp wp3370-18-2675-9426-20.doc Bandra, Mumbai. 3. Miss. Navneet Kaur Harbhajansing Kundles @ Mrs. Navneet Kaur Ravi Rana, Presently residing at Room No. 600/C, Marathwada Chawl, Hill No.2, Narayan Nagar, Ghatkopar (W), Mumbai -400 086. ... Respondents --- WITH WRIT PETITION (LDG.) NO. 9426 OF 2020 Miss. Navneet Kaur Harbhajansing Kundles @ Mrs. Navneet Kaur Ravi Rana, Age-35 years, Occu. Social Work. R/at Room No. 600/C, Marathwada Chawl, Hill No.2, Narayan Nagar, Ghatkopar (W), Mumbai -400 086 At present residing at - Ganga Savitri Banglow, Plot No. -

List of OBC Approved by SC/ST/OBC Welfare Department in Delhi

List of OBC approved by SC/ST/OBC welfare department in Delhi 1. Abbasi, Bhishti, Sakka 2. Agri, Kharwal, Kharol, Khariwal 3. Ahir, Yadav, Gwala 4. Arain, Rayee, Kunjra 5. Badhai, Barhai, Khati, Tarkhan, Jangra-BrahminVishwakarma, Panchal, Mathul-Brahmin, Dheeman, Ramgarhia-Sikh 6. Badi 7. Bairagi,Vaishnav Swami ***** 8. Bairwa, Borwa 9. Barai, Bari, Tamboli 10. Bauria/Bawria(excluding those in SCs) 11. Bazigar, Nat Kalandar(excluding those in SCs) 12. Bharbhooja, Kanu 13. Bhat, Bhatra, Darpi, Ramiya 14. Bhatiara 15. Chak 16. Chippi, Tonk, Darzi, Idrishi(Momin), Chimba 17. Dakaut, Prado 18. Dhinwar, Jhinwar, Nishad, Kewat/Mallah(excluding those in SCs) Kashyap(non-Brahmin), Kahar. 19. Dhobi(excluding those in SCs) 20. Dhunia, pinjara, Kandora-Karan, Dhunnewala, Naddaf,Mansoori 21. Fakir,Alvi *** 22. Gadaria, Pal, Baghel, Dhangar, Nikhar, Kurba, Gadheri, Gaddi, Garri 23. Ghasiara, Ghosi 24. Gujar, Gurjar 25. Jogi, Goswami, Nath, Yogi, Jugi, Gosain 26. Julaha, Ansari, (excluding those in SCs) 27. Kachhi, Koeri, Murai, Murao, Maurya, Kushwaha, Shakya, Mahato 28. Kasai, Qussab, Quraishi 29. Kasera, Tamera, Thathiar 30. Khatguno 31. Khatik(excluding those in SCs) 32. Kumhar, Prajapati 33. Kurmi 34. Lakhera, Manihar 35. Lodhi, Lodha, Lodh, Maha-Lodh 36. Luhar, Saifi, Bhubhalia 37. Machi, Machhera 38. Mali, Saini, Southia, Sagarwanshi-Mali, Nayak 39. Memar, Raj 40. Mina/Meena 41. Merasi, Mirasi 42. Mochi(excluding those in SCs) 43. Nai, Hajjam, Nai(Sabita)Sain,Salmani 44. Nalband 45. Naqqal 46. Pakhiwara 47. Patwa 48. Pathar Chera, Sangtarash 49. Rangrez 50. Raya-Tanwar 51. Sunar 52. Teli 53. Rai Sikh 54 Jat *** 55 Od *** 56 Charan Gadavi **** 57 Bhar/Rajbhar **** 58 Jaiswal/Jayaswal **** 59 Kosta/Kostee **** 60 Meo **** 61 Ghrit,Bahti, Chahng **** 62 Ezhava & Thiyya **** 63 Rawat/ Rajput Rawat **** 64 Raikwar/Rayakwar **** 65 Rauniyar ***** *** vide Notification F8(11)/99-2000/DSCST/SCP/OBC/2855 dated 31-05-2000 **** vide Notification F8(6)/2000-2001/DSCST/SCP/OBC/11677 dated 05-02-2004 ***** vide Notification F8(6)/2000-2001/DSCST/SCP/OBC/11823 dated 14-11-2005 . -

Cow Care in Hindu Animal Ethics Kenneth R

THE PALGRAVE MACMILLAN ANIMAL ETHICS SERIES Cow Care in Hindu Animal Ethics Kenneth R. Valpey The Palgrave Macmillan Animal Ethics Series Series Editors Andrew Linzey Oxford Centre for Animal Ethics Oxford, UK Priscilla N. Cohn Pennsylvania State University Villanova, PA, USA Associate Editor Clair Linzey Oxford Centre for Animal Ethics Oxford, UK In recent years, there has been a growing interest in the ethics of our treatment of animals. Philosophers have led the way, and now a range of other scholars have followed from historians to social scientists. From being a marginal issue, animals have become an emerging issue in ethics and in multidisciplinary inquiry. Tis series will explore the challenges that Animal Ethics poses, both conceptually and practically, to traditional understandings of human-animal relations. Specifcally, the Series will: • provide a range of key introductory and advanced texts that map out ethical positions on animals • publish pioneering work written by new, as well as accomplished, scholars; • produce texts from a variety of disciplines that are multidisciplinary in character or have multidisciplinary relevance. More information about this series at http://www.palgrave.com/gp/series/14421 Kenneth R. Valpey Cow Care in Hindu Animal Ethics Kenneth R. Valpey Oxford Centre for Hindu Studies Oxford, UK Te Palgrave Macmillan Animal Ethics Series ISBN 978-3-030-28407-7 ISBN 978-3-030-28408-4 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-28408-4 © Te Editor(s) (if applicable) and Te Author(s) 2020. Tis book is an open access publication. Open Access Tis book is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made. -

Download This Issue As A

MICHAEL GERRARD ‘72 COLLEGE HONORS FIVE IS THE GURU OF DISTINGUISHED ALUMNI CLIMATE CHANGE LAW WITH JOHN JAY AWARDS Page 26 Page 18 Columbia College May/June 2011 TODAY Nobel Prize-winner Martin Chalfie works with College students in his laboratory. APassion for Science Members of the College’s science community discuss their groundbreaking research ’ll meet you for a I drink at the club...” Meet. Dine. Play. Take a seat at the newly renovated bar grill or fine dining room. See how membership in the Columbia Club could fit into your life. For more information or to apply, visit www.columbiaclub.org or call (212) 719-0380. The Columbia University Club of New York 15 West 43 St. New York, N Y 10036 Columbia’s SocialIntellectualCulturalRecreationalProfessional Resource in Midtown. Columbia College Today Contents 26 20 30 18 73 16 COVER STORY ALUMNI NEWS DEPARTMENTS 2 20 A PA SSION FOR SCIENCE 38 B OOKSHELF LETTERS TO THE Members of the College’s scientific community share Featured: N.C. Christopher EDITOR Couch ’76 takes a serious look their groundbreaking work; also, a look at “Frontiers at The Joker and his creator in 3 WITHIN THE FA MILY of Science,” the Core’s newest component. Jerry Robinson: Ambassador of By Ethan Rouen ’04J, ’11 Business Comics. 4 AROUND THE QU A DS 4 Reunion, Dean’s FEATURES 40 O BITU A RIES Day 2011 6 Class Day, 43 C L A SS NOTES JOHN JA Y AW A RDS DINNER FETES FIVE Commencement 2011 18 The College honored five alumni for their distinguished A LUMNI PROFILES 8 Senate Votes on ROTC professional achievements at a gala dinner in March. -

Caste, Trade Or Class: Historical Transition in Stratification Structure in Rural Punjab

Journal of the Punjab University Historical Society Volume: 34, No. 01, January – June 2021 Ayesha Farooq * Caste, Trade or Class: Historical Transition in Stratification Structure in Rural Punjab Abstract Dynamics of caste have modified over time due to occupational changes, economic positions and religious enlightenment. However, it is not entirely replaced by any new stratification structure, resulting in much confusion regarding the adopted caste titles in the community. The present research has been conducted in a village named Mohla in the Punjab, Pakistan. Findings revealed resistance of young generation towards the existing caste system and they were recognized by trades of their forefather. Economic factor found important for such differences, besides education and migration. There has been fluidity of caste perception over generation and across social strata; young, educated, economically better off craftsmen and women condemned caste division whereas most of the landowners emphasized the importance of caste system. Shift in basis of social differentiation, role of chieftain has become negligible as majority of them tend to resolve their issues by themselves and go to police or courts. Keywords: Caste system, Class structure, social stratification, intergenerational differences, economics, migration, infrastructure. Introduction The present paper aims to assess stratification system in a rural community named Mohla, situated in District Gujrat of Punjab, Pakistan. Implications of caste on various aspects of social life are also observed. Eglar studied this village five decades ago and found caste stratification as foremost aspect in determining social status and life opportunities.1 In this study, we intend to look into the differences between old and young villager’s perception regarding caste system. -

SOCIAL DYNAMIC STATUS and ITS REFLECTION on USE of FAMILY PLANNING METHODS in an INDIAN VILLAGE: the CASE of ‘GAURA’ VILLAGE (UP), INDIA Vimalesh Kumar Singh &

52/TheThe Third Third Pole, Pole Vol. 5-7, PP 52-61:2007 SOCIAL DYNAMIC STATUS AND ITS REFLECTION ON USE OF FAMILY PLANNING METHODS IN AN INDIAN VILLAGE: THE CASE OF ‘GAURA’ VILLAGE (UP), INDIA Vimalesh Kumar Singh &. M. B. Singh Department of Geography, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi-221005, U P India [email protected] Abstract Present paper aims at examining the recent transformation of the village society, which is caste ridden, conservative and sluggish to adopt new innovations. The paper is mainly based on primary data collected through interview schedules from 80 families and 123 married women respondents on stratified random basis from Gaura village of Mirzapur District, Uttar Pradesh. On the basis of social dynamic status in a rural population of Gaura village the study pinpoints that Yadav, Gupta, Lohar, and Harijan (Scheduled caste) castes are static communities while Kurmi has been found single progressive caste. Brahmin and Kumhar are categorized as retrogressive castes. The paper also highlights the position of spouse on the practice of family planning methods. This study was undertaken to assess the extent of awareness among married women towards the various aspects of family planning. It was found that majority of the respondents had knowledge and awareness about various aspects of family planning but its adoption is of low magnitude. Women were the major users of permanently contraceptives (tubectomy) as contrary to men. Some women were found with the use of oral pills but the use of loops, condom and copper-T was almost absent in the study village. Key words: Family planning attitude, never users, contraceptives, caste, traditional social hierarchy. -

Diverse Genetic Origin of Indian Muslims: Evidence from Autosomal STR Loci

Journal of Human Genetics (2009) 54, 340–348 & 2009 The Japan Society of Human Genetics All rights reserved 1434-5161/09 $32.00 www.nature.com/jhg ORIGINAL ARTICLE Diverse genetic origin of Indian Muslims: evidence from autosomal STR loci Muthukrishnan Eaaswarkhanth1,2, Bhawna Dubey1, Poorlin Ramakodi Meganathan1, Zeinab Ravesh2, Faizan Ahmed Khan3, Lalji Singh2, Kumarasamy Thangaraj2 and Ikramul Haque1 The origin and relationships of Indian Muslims is still dubious and are not yet genetically well studied. In the light of historically attested movements into Indian subcontinent during the demic expansion of Islam, the present study aims to substantiate whether it had been accompanied by any gene flow or only a cultural transformation phenomenon. An array of 13 autosomal STR markers that are common in the worldwide data sets was used to explore the genetic diversity of Indian Muslims. The austere endogamy being practiced for several generations was confirmed by the genetic demarcation of each of the six Indian Muslim communities in the phylogenetic assessments for the markers examined. The analyses were further refined by comparison with geographically closest neighboring Hindu religious groups (including several caste and tribal populations) and the populations from Middle East, East Asia and Europe. We found that some of the Muslim populations displayed high level of regional genetic affinity rather than religious affinity. Interestingly, in Dawoodi Bohras (TN and GUJ) and Iranian Shia significant genetic contribution from West Asia, especially Iran (49, 47 and 46%, respectively) was observed. This divulges the existence of Middle Eastern genetic signatures in some of the contemporary Indian Muslim populations. -

Annual Report 2009–2010 Columbia University Columbia 2009–2010 Report Annual Nstitute

WEATHERHEAD ANNUAL REPORT 2009 – 2 010 E AST A SIAN I NSTITUTE ANNUAL REPORT 2009–2010 COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY Weatherhead East Asian Institute Columbia University International Affairs Building, 9th floor MC 3333 420 West 118th Street New York, NY 10027 Tel: 212-854-2592 Fax: 212-749-1497 www.columbia.edu/weai TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 LETTER FROM THE DIRECTOR 1 2 THE WEATHERHEAD EAST ASIAN INSTITUTE AT COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2 3 THE RESEARCH COMMUNITY 3 4 PUBLICATIONS 26 5 RESEARCH CENTERS AT THE WEATHERHEAD EAST ASIAN INSTITUTE AND AFFILIATED COLUMBIA PROGRAMS 30 6 PUBLIC PROGRAMMING 34 7 GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES 39 8 STUDENTS 43 9 ASIA FOR EDUCATORS PROGRAM 47 10 AdMINISTRATIVE STAFF OF THE WEATHERHEAD EAST ASIAN INSTITUTE 50 11 FUNDING SOURCES 51 12 COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY MAP: MORNINGSIDE CAMPUS & ENVIRONS 52 1 LETTER FROM THE DIRECTOR Over the past year, the Weatherhead East Asian Institute’s leading position in regional studies was amply reaffirmed. A fitting finale to our 60th anniversary celebrations was the June 13, 2010, symposium in Taipei, “Taiwan in the Twenty-first Century: Politics, Economy and Society.” This symposium continued WEAI’s outreach programs in East Asia to local Columbia alumni and to all prior visiting scholars, professional fellows, or participants at WEAI. The first three symposia were held in Beijing, Tokyo, and Seoul during May and June of 2009, and planning is now under way for a May 2011 sym- posium to take place in Hong Kong. As with the earlier events, the Taipei symposium involved close cooperation with the Columbia Alumni Association. The local signifi- cance of the symposium was underscored by the keynote speaker, Vincent Siew, vice president of the Republic of China (Taiwan), and by the meeting on the following day of symposium panelists and speakers with ROC President Ma Ying-jeou. -

Gender Quotas and Caste in India

Competing Inequalities? Gender Quotas and Caste in India Alexander Lee* Varun Karekurve-Ramachandra† March 27, 2019 Short Title: Competing Inequalities Key Words: Gender Quotas, India, Women in Politics, Caste, Intersectionality *Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science, University of Rochester. 333 Harkness Hall Rochester NY 14627. Email: [email protected] †PhD Student, Department of Political Science, University of Rochester. 333 Harkness Hall Rochester NY 14627. Email: [email protected]. The authors gratefully acknowledge Charles E Lanni fellowship that funded a part of this research. The authors also thank Prof. Rajeev Gowda, Ramprasad Alva and Avinash Gowda for help and encouragement during fieldwork in Delhi, the Takshashila Insti- tution and PRS Legislative Research for providing working space and amazing hospitality in Bengaluru and New Delhi respectively, and Harnidh Kaur for research assistance. Alessio Albarello, Sergio Ascensio, Emiel Awad, Tiffany Barnes, Salil Bijur, Saurabh Chandra, Praveen Chandrashekaran, Zuheir Desai, Ramanjit Duggal, Olga Gasparyan, Gretchen Helmke, Aravind Gayam, Aparna Goel, Nidhi Gupta, Gleason Judd, Adam Kaplan, Pranay Kotasthane, Sanjay Kumar, M.R.Madhavan, Prachee Mishra, Meenakshi Narayanan, Sundeep Narwani, Jack Paine, Aman Panwar, Akhila Prakash, Vibhor Relhan, Maria Silfa, Pavan Srinath, Ramachan- dra Shingare, Aruna Urs and Yannis Vassiliadis provided constructive suggestions, help, and comments. Responsibility for any errors remains our own. 1 Competing Inequalities? Gender Quotas and Caste in India Abstract How do political gender quotas affect representation? We suggest that when gender attitudes are correlated with ethnicity, promoting female politicians may reduce the descriptive representation of traditionally disadvantaged ethnic groups. To assess this idea, we examine the consequences of the implementation of random electoral quotas for women on the representation of caste groups in Delhi. -

The History of Punjab Is Replete with Its Political Parties Entering Into Mergers, Post-Election Coalitions and Pre-Election Alliances

COALITION POLITICS IN PUNJAB* PRAMOD KUMAR The history of Punjab is replete with its political parties entering into mergers, post-election coalitions and pre-election alliances. Pre-election electoral alliances are a more recent phenomenon, occasional seat adjustments, notwithstanding. While the mergers have been with parties offering a competing support base (Congress and Akalis) the post-election coalition and pre-election alliance have been among parties drawing upon sectional interests. As such there have been two main groupings. One led by the Congress, partnered by the communists, and the other consisting of the Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD) and Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). The Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) has moulded itself to joining any grouping as per its needs. Fringe groups that sprout from time to time, position themselves vis-à-vis the main groups to play the spoiler’s role in the elections. These groups are formed around common minimum programmes which have been used mainly to defend the alliances rather than nurture the ideological basis. For instance, the BJP, in alliance with the Akali Dal, finds it difficult to make the Anti-Terrorist Act, POTA, a main election issue, since the Akalis had been at the receiving end of state repression in the early ‘90s. The Akalis, in alliance with the BJP, cannot revive their anti-Centre political plank. And the Congress finds it difficult to talk about economic liberalisation, as it has to take into account the sensitivities of its main ally, the CPI, which has campaigned against the WTO regime. The implications of this situation can be better understood by recalling the politics that has led to these alliances. -

State, Marriage and Household Amongst the Gaddis of North India

GOVERNING MORALS: STATE, MARRIAGE AND HOUSEHOLD AMONGST THE GADDIS OF NORTH INDIA Kriti Kapila London School of Economics and Political Science University of London PhD UMI Number: U615831 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615831 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 I H cS £ S h S) IS ioaqsci% Abstract This thesis is an anthropological study of legal governance and its impact on kinship relations amongst a migratory pastoralist community in north India. The research is based on fieldwork and archival sources and is concerned with understanding the contest between ‘customary’ and legal norms in the constitution of public moralities amongst the Gaddis of Himachal Pradesh. The research examines on changing conjugal practices amongst the Gaddis in the context of wider changes in their political economy and in relation to the colonial codification of customary law in colonial Punjab and the Hindu Marriage Succession Acts of 1955-56. The thesis investigates changes in the patterns of inheritance in the context of increased sedentarisation, combined with state legislation and intervention. -

CASTE SYSTEM in INDIA Iwaiter of Hibrarp & Information ^Titntt

CASTE SYSTEM IN INDIA A SELECT ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of iWaiter of Hibrarp & information ^titntt 1994-95 BY AMEENA KHATOON Roll No. 94 LSM • 09 Enroiament No. V • 6409 UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF Mr. Shabahat Husaln (Chairman) DEPARTMENT OF LIBRARY & INFORMATION SCIENCE ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 1995 T: 2 8 K:'^ 1996 DS2675 d^ r1^ . 0-^' =^ Uo ulna J/ f —> ^^^^^^^^K CONTENTS^, • • • Acknowledgement 1 -11 • • • • Scope and Methodology III - VI Introduction 1-ls List of Subject Heading . 7i- B$' Annotated Bibliography 87 -^^^ Author Index .zm - 243 Title Index X4^-Z^t L —i ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to express my sincere and earnest thanks to my teacher and supervisor Mr. Shabahat Husain (Chairman), who inspite of his many pre Qoccupat ions spared his precious time to guide and inspire me at each and every step, during the course of this investigation. His deep critical understanding of the problem helped me in compiling this bibliography. I am highly indebted to eminent teacher Mr. Hasan Zamarrud, Reader, Department of Library & Information Science, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh for the encourage Cment that I have always received from hijft* during the period I have ben associated with the department of Library Science. I am also highly grateful to the respect teachers of my department professor, Mohammadd Sabir Husain, Ex-Chairman, S. Mustafa Zaidi, Reader, Mr. M.A.K. Khan, Ex-Reader, Department of Library & Information Science, A.M.U., Aligarh. I also want to acknowledge Messrs. Mohd Aslam, Asif Farid, Jamal Ahmad Siddiqui, who extended their 11 full Co-operation, whenever I needed.