American Sociological Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mohamed Ramadan I Arrêté À Trois Reprises En Six Mois Au Cours De L’Année 2014

© IDHAE & IDHBB Institut des Droits de l’Homme des Avocats Européens – European Bar Human Rights Institute & Institut des Droits de l’Homme du barreau de Bordeaux – Human Rights Institute of the Bar of Bordeaux ISBN 978-99959-970-3-8 ISSN : 2354-4554 Le Code de la propriété intellectuelle interdit les copies ou reproductions destinées à une utilisation collective. Toute représentation ou reproduction intégrale ou partielle faite par quelque procédé que ce soit, sans le consentement de l’auteur ou de ses ayant cause, est illicite et constitue une contrefaçon, aux termes des articles L.335-2 et suivants du Code de la propriété intellectuelle 3 INSTITUT DES DROITS DE L’HOMME DES AVOCATS EUROPÉENS ISTITUTO DEI DIRITTI DELL'UOMO DEGLI AVVOCATI EUROPEI – INSTITUT FÜR MENSCHENRECHTE DER EUROPÄISCHEN ANWÄLTE – ΙΝΣΤΙΤΟΥΤΟ ΑΝΘΡΩΠΙΝΩΝ ΔΙΚΑΙΩΜΑΤΩΝ ΤΩΝ ΕΥΡΩΠΑΙΩΝ ΔΙΚΗΓΟΡΩΝ – INSTITUDO DE DERECHOS HUMANOS DE ABOGADOS EUROPEOS – INSTITUT LIDSKÝCH PRAV EVROPSKÝCH ADVOKATU – INSTYTUT ADWOKATÓW EUROPEJSKICH NA RZECZ PRAW CZŁOWIEKA – INSTITUT FOR MENNESKERETTIGHEDER AF EROPEAEISKE ADVOKATER – INSTITUTO DE DIREITOS HUMANOS DOS ADVOGADOS EUROPEUS EUROPEAN BAR HUMAN RIGHTS INSTITUTE Ce supplément SPECIAL ÉGYPTE est publié à l’occasion de La Journée mondiale de l’avocat en danger 2018 www.idhae.org 4 5 Éphéméride (non exhaustif) 1er mars 2013 : Romani Murad Saad condamné par contumace à un an de prison et 500 Livres égyptiennes EGP (52,30 €) d'amende pour diffamation de la religion. 29 mars 2013 : Maheinour el-Massry, Mohamed Ramadan, Amr Said, Mohamed Samir et Nasser Ahmed arrêtés à Alexandrie et victimes de violences pour avoir voulu défendre des manifestants arrêtés lors d’une manifestation. -

Petition To: United Nations Working

PETITION TO: UNITED NATIONS WORKING GROUP ON ARBITRARY DETENTION Mr Mads Andenas (Norway) Mr José Guevara (Mexico) Ms Shaheen Ali (Pakistan) Mr Sètondji Adjovi (Benin) Mr Vladimir Tochilovsky (Ukraine) HUMAN RIGHTS COUNCIL UNITED NATIONS GENERAL ASSEMBLY COPY TO: UNITED NATIONS SPECIAL RAPPORTEUR ON THE PROMOTION AND PROTECTION OF THE RIGHT TO FREEDOM OF OPINION AND EXPRESSION, MR DAVID KAYE; UNITED NATIONS SPECIAL RAPPORTEUR ON THE RIGHTS TO FREEDOM OF PEACEFUL ASSEMBLY AND OF ASSOCIATION, MR MAINA KIAI; UNITED NATIONS SPECIAL RAPPORTEUR ON THE SITUATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS DEFENDERS, MR MICHEL FORST. in the matter of Alaa Abd El Fattah (the “Petitioner”) v. Egypt _______________________________________ Petition for Relief Pursuant to Commission on Human Rights Resolutions 1997/50, 2000/36, 2003/31, and Human Rights Council Resolutions 6/4 and 15/1 Submitted by: Media Legal Defence Initiative Electronic Frontier Foundation The Grayston Centre 815 Eddy Street 28 Charles Square San Francisco CA 94109 London N1 6HT BASIS FOR REQUEST The Petitioner is a citizen of the Arab Republic of Egypt (“Egypt”), which acceded to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (“ICCPR”) on 14 January 1982. 1 The Constitution of the Arab Republic of Egypt 2014 (the “Constitution”) states that Egypt shall be bound by the international human rights agreements, covenants and conventions it has ratified, which shall have the force of law after publication in accordance with the conditions set out in the Constitution. 2 Egypt is also bound by those principles of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (“UDHR”) that have acquired the status of customary international law. -

Sourcing the Arab Spring: a Case Study of Andy Carvin's Sources During the Tunisian and Egyptian Revolutions

Sourcing the Arab Spring: A Case Study of Andy Carvin’s Sources During the Tunisian and Egyptian Revolutions Paper presented at the International Symposium on Online Journalism in Austin, TX, April 2012 Alfred Hermida Associate professor, Graduate School of Journalism, University of British Columbia Seth C. Lewis Assistant professor, School of Journalism & Mass Communication, University of Minnesota Rodrigo Zamith Doctoral student, School of Journalism & Mass Communication, University of Minnesota Contact: Alfred Hermida UBC Graduate School of Journalism 6388 Crescent Road Vancouver, BC, V6T 1Z2 Canada Tel: 1 604 827 3540 E-mail: [email protected] Abstract This paper presents a case study on the use of sources by National Public Radio's Andy Carvin on Twitter during key periods of the 2011 Tunisian and Egyptian uprisings. It examines the different actor types on the social media platform to reveal patterns of sourcing used by the NPR social media strategist, who emerged as a key broker of information on Twitter during the Arab Spring. News sourcing is a critical element in the practice of journalism as it shapes from whom journalists get their information and what type of information they obtain. Numerous studies have shown that journalists privilege elite sources who hold positions of power in society. This study evaluates whether networked and distributed social media platforms such as Twitter expand the range of actors involved in the construction of the news through a quantitative content analysis of the sources cited by Carvin. The results show that non-elite sources had a greater influence over the content flowing through his Twitter stream than journalists or other elite sources. -

Complete Issue As

yber C y b e r O r i e n t Online Journal of the Virtual Middle East Vol. 6, Iss. 1, 2012 ISSN 1804-3194 CyberOrient Online Journal of the Virtual Middle East © American Anthropological Association 2012 CyberOrient is a peer-reviewed online journal published by the American Anthropological Association in collaboration with the Faculty of Arts of Charles University in Prague. Editor-in-Chief: Daniel Martin Varisco Managing Editor: Vit Sisler ISSN 1804-3194 http://www.cyberorient.net yber Index - Editorial Ines Braune – The Net Worth of the Arab Spring Page 4 - Articles Mohammed El-Nawawy and Sahar Khamis – Political Activism 2.0: Comparing the Role of Social Media in Egypt’s “Facebook Revolution” and Iran’s “Twitter Uprising” Page 8 Heidi A. Campbell and Diana Hawk – Al Jazeera’s Framing of Social Media During the Arab Spring Page 34 Donatella Della Ratta and Augusto Valeriani – Remixing the Spring!: Connective leadership and read-write practices in the 2011 Arab uprisings Page 52 Anton Root – Beyond the Soapbox: Facebook and the Public Sphere in Egypt Page 77 - Comments Mervat Youssef and Anup Kumar – Beyond the Soapbox: Facebook and the Public Sphere in Egypt Page 101 - Reviews Jon W. Anderson – The Digital Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy: Informati- on Technology and Political Islam Page 133 Marek Cejka – The Arab Revolution: The Lessons from the Democratic Uprising Page 141 3 yber C y b e r O rient, Vol. 6 , I s s . 1 , 2 0 1 2 The Net Worth of the Arab Spring Ines Braune Keywords Islam and civil society, Middle East, Arab Spring, information and communication technology, media studies, Middle Eastern studies, social networks When I was asked to be the guest editor of the current issue of CyberOrient, I realized this is a welcome opportunity to arrange and re-sort some aspects, points, and arguments about the role of the media during the Arab Spring. -

News Coverage Prepared For: the European Union Delegation to Egypt

News Coverage prepared for: The European Union delegation to Egypt . Disclaimer: “This document has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union. The contents of this document are the sole responsibility of authors of articles and under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of IPSOS or the European Union.” 1 . Thematic Headlines Domestic Scene Security Source Denies Bid on Saudi Envoy’s Life Made Electoral Campaigns Violations to Be Referred to HPEC Ganzouri: I’d Resign If Cabinet Reshuffle Took Place Shafiq Takes Lead in Presidential Campaign More MPs Refuse Vote of Censure against Government Weapons Found with Defense Ministry Sitter-Ins The Government Crisis Police Protests Escalate Al-Ahram Updates on Presidential Campaigns The Revolution Youth Coalition Supports Abu al-Futouh A demonstration Calling for the Return of the Saudi Ambassador An Interview with Hamadain Sabahi Presidential Elections Observers Islamic Mediation between Abu al-Futouh and Islamic Powers Police Officers Give the Minatory a Grace Shurouk Updates on Presidential Race Regional Development Israel Must Be Prepared for Future Confrontation with Egypt, Says Ex-Defense Minister 2 Newspapers (02/05/2012) Pages: 1 Author: Raja Leilah and Nasr Zaalouk A demonstration Calling for the Return of the Saudi Ambassador An official source denied what was reported by the London-based al-Haya newspapers about an alleged assassination attempt against the Saudi Ambassador to Egypt Ahmad Qattan in Cairo. While investigations continue in the case of the Egyptian national Ahmad al-Gizawi who is facing charges of drugs dealing in Saudi Arabia, dozens of Egyptians and political activists demonstrated in front of the Saudi Embassy in Cairo calling for the return of the Saudi Ambassador. -

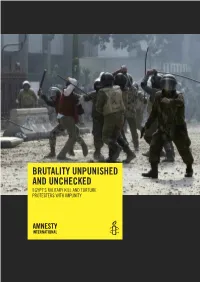

Brutality Unpunished and Unchecked

brutality unpunished and unchecked EGYPT’S MILITARY KILL AND TORTURE PROTESTERS WITH IMPUNITY amnesty international is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the universal declaration of human rights and other international human rights standards. we are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. First published in 2012 by amnesty international ltd peter benenson house 1 easton street london wc1X 0dw united kingdom © amnesty international 2012 index: mde 12/017/2012 english original language: english printed by amnesty international, international secretariat, united kingdom all rights reserved. this publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. the copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. to request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover phot o: egyptian soldiers beating a protester during clashes near the cabinet offices by cairo’s tahrir square on 16 december 2011. © mohammed abed/aFp/getty images amnesty.org CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................5 2. MASPERO PROTESTS: ASSAULT OF COPTS.............................................................11 3. CRACKDOWN ON CABINET OFFICES SIT-IN.............................................................17 4. -

Army Sets 48-Hour Ultimatum

AILY EWS TUESDAY, JULY 2, 2013 N D ISSUE NO. 2226 NEWSTAND PRICE LE 4.00 EGYPT www.thedailynewsegypt.com Egypt’s Only Daily Independent Newspaper In English BLOCK PARTY UNDER SIEGE SAD PANDA Cairo’s Mugamma is one of many Eight killed and 70 injured during New iconic character, emblematic government buildings nationwide an attack on the Brotherhood’s of revolutionary melancholy, to be blockaded by protesters headquarters in Moqattam flourishes in Cairo street art 2 3 8 Kerry confident about safety Army sets 48-hour ultimatum of US embassy in Cairo THE ARMED FORCES SAYS IT WILL PRESENT ITS OWN ROADMAP FOR THE 30 June protests draw comments from US Secretary COUNTRY IF POLITICAL FIGHTING DOES NOT END ON WEDNESDAY Kerry, President Obama, and German foreign minister By Nourhan Dakroury “What is clear right now is that al- By Basil El-Dabh, Rana Muham- though Mr Morsi was elected demo- mad Taha, and Hend Kortam Secretary of State John Kerry an- cratically, there is more work to be nounced on Sunday his keen attention done to create the conditions in which The Armed Forces will implement to the developments in Egypt and con- everybody feels their voices are heard,” a roadmap for the country if the firmed his confidence in the safety of the he concluded. Presidency and his opposition can- US embassy in Cairo as well as its staff. The United Nations warned on Mon- not resolve their differences within “Egypt is a great concern to all of day that the current political situation 48 hours. us,” Kerry said, explaining that he held in Egypt will have a “significant impact” “The Armed Forces reiterates talks with Gulf country leaders about on the democratic transformation of its call to meet the demands of the the political situation in Egypt, in addi- other countries in the Middle East. -

Mobilisation Et Répression Au Caire En Période De Transition (Juin 2010-Juin 2012) Nadia Aboushady

Mobilisation et répression au Caire en période de transition (juin 2010-juin 2012) Nadia Aboushady To cite this version: Nadia Aboushady. Mobilisation et répression au Caire en période de transition (juin 2010-juin 2012). Science politique. 2013. dumas-00955609 HAL Id: dumas-00955609 https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-00955609 Submitted on 4 Mar 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne UFR 11- Science politique Programme M2 recherche : Sociologie et institutions du politique Master de science politique Mobilisation et répression au Caire en période de transition (juin 2010-juin 2012) Nadia Abou Shady Mémoire dirigé par Isabelle Sommier juin 2013 Sommaire Sommaire……………………………………………………………………………………...2 Liste d‟abréviation…………………………………………………………………………….4 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………5 Premier Chapitre. De la mort de Khaled Saïd au « vendredi de la colère » : répression étatique et mobilisation contestataire ascendante………………………………………...35 Section 1 : L’origine du cycle de mobilisation contestataire……………………………………...36 -

Urgent Action

Further information on UA: 324/13 Index: MDE 12/002/2014 Egypt Date: 13 January 2014 URGENT ACTION FIRST JAILINGS UNDER NEW PROTEST LAW Activists Ahmed Maher and Mohamed Adel, and blogger Ahmed Douma, are facing three years in prison for breaking Egypt’s repressive new protest law. Two of the men are prisoners of conscience. The men do not have access to their lawyers or families. The Abdeen Misdemeanour Court convicted Ahmed Maher, Mohamed Adel and Ahmed Douma on 22 December of taking part in an unauthorized protest on 30 November 2013, “attacking the security forces, destroying public property and disturbing public order”. The court, sitting at the Tora Police Institute, sentenced the men to three years in prison with hard labour and a fine of LE50,000 (US$7,185). The men will remain in prison during the appeal process. The court of appeal convened at the Tora Police Institute on 9 January, but postponed the hearing to 20 January at the request of the defendants’ lawyers. The lawyers had asked the court for an extension to get a copy of the full case-file and to hear the defendants’ opinions about the case. The prison authorities have held the men in solitary confinement since their arrest. Lawyers have told Amnesty International that they have not had access to the men since their conviction, despite repeated requests. On 22 December 2013, the men began a series of hunger-strikes in protest at their detention in Tora Prison. Amnesty International considers Ahmed Maher and Ahmed Douma to be prisoners of conscience, and that Mohamed Adel is likely to be a prisoner of conscience, detained solely for peacefully exercising their right to freedom of assembly. -

Microlevel Movements Matter: Persuasion, Identity Performance, Performative Agency, and Resistance in Egypt on Twitter During the Egyptian Arab Spring

University of Texas at El Paso ScholarWorks@UTEP Open Access Theses & Dissertations 2020-01-01 Microlevel Movements Matter: Persuasion, Identity Performance, Performative Agency, And Resistance In Egypt On Twitter During The Egyptian Arab Spring Audrey Cisneros University of Texas at El Paso Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.utep.edu/open_etd Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Cisneros, Audrey, "Microlevel Movements Matter: Persuasion, Identity Performance, Performative Agency, And Resistance In Egypt On Twitter During The Egyptian Arab Spring" (2020). Open Access Theses & Dissertations. 3068. https://scholarworks.utep.edu/open_etd/3068 This is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UTEP. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UTEP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MICROLEVEL MOVEMENTS MATTER: PERSUASION, IDENTITY PERFORMANCE, PERFORMATIVE AGENCY, AND RESISTANCE IN EGYPT ON TWITTER DURING THE EGYPTIAN ARAB SPRING AUDREY FAY CISNEROS Doctoral Program in English Rhetoric and Composition APPROVED: Kate Mangelsdorf, Ph.D., Chair Isabel Baca, Ph.D. Roberto Avant-Mier, Ph.D. Stephen L. Crites, Jr., Ph.D. Dean of the Graduate School Copyright © by Audrey Fay Cisneros 2020 Dedication For my Mother, Beatriz Cisneros. MICROLEVEL MOVEMENTS MATTER: PERSUASION, IDENTITY PERFORMANCE, PERFORMATIVE AGENCY, AND RESISTANCE IN EGYPT ON TWITTER DURING THE EGYPTIAN ARAB SPRING by AUDREY FAY CISNEROS, MA, BA DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at El Paso in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of English, Rhetoric and Composition THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT EL PASO May 2020 Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge and thank my committee for their invaluable feedback throughout the dissertation process. -

![Égypte/Monde Arabe, 13 | 2015, « Nouvelles Luttes Autour Du Genre En Egypte Depuis 2011 » [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 10 Novembre 2017, Consulté Le 24 Septembre 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5053/%C3%A9gypte-monde-arabe-13-2015-%C2%AB-nouvelles-luttes-autour-du-genre-en-egypte-depuis-2011-%C2%BB-en-ligne-mis-en-ligne-le-10-novembre-2017-consult%C3%A9-le-24-septembre-2020-2155053.webp)

Égypte/Monde Arabe, 13 | 2015, « Nouvelles Luttes Autour Du Genre En Egypte Depuis 2011 » [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 10 Novembre 2017, Consulté Le 24 Septembre 2020

Égypte/Monde arabe 13 | 2015 Nouvelles luttes autour du genre en Egypte depuis 2011 New gender-related Struggles in Egypt since 2011 Leslie Piquemal (dir.) Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ema/3492 DOI : 10.4000/ema.3492 ISSN : 2090-7273 Éditeur CEDEJ - Centre d’études et de documentation économiques juridiques et sociales Édition imprimée Date de publication : 10 novembre 2015 ISBN : 9782905838865 ISSN : 1110-5097 Référence électronique Leslie Piquemal (dir.), Égypte/Monde arabe, 13 | 2015, « Nouvelles luttes autour du genre en Egypte depuis 2011 » [En ligne], mis en ligne le 10 novembre 2017, consulté le 24 septembre 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ema/3492 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/ema.3492 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 24 septembre 2020. © Tous droits réservés 1 Depuis le soulèvement de 2011 en Égypte, les problématiques de genre ont émergé sous différentes formes dans le cadre des mouvements protestataires – révolutionnaires, réactionnaires – et plus largement, dans celui des transformations sociales se produisant autour et entre ces vagues de mobilisation. Alors que les relations entre citoyens et autorités étatiques ont été contestées, modifiées, puis repoussées dans une direction réactionnaire, comment les relations de genre ont-elles été contestées depuis 2011 ? Quels nouveaux imaginaires, quels nouveaux rôles et identités ont été revendiqués ? Quelles mobilisations se sont construites face à l’essor saisissant des violences sexistes dans l’espace public ? Quatre ans après le début de la période révolutionnaire, ce numéro d’Égypte/Monde arabe explore les nouvelles luttes liées au genre en Égypte au prisme de la sociologie, l’anthropologie et la science politique. -

Communications Sent, 1 June to 30 November 2013

United Nations A/HRC/26/21 General Assembly Distr.: General 2 June 2014 English/French/Spanish only Human Rights Council Twenty-sixth session Agenda items 3, 4, 7, 9 and 10 Promotion and protection of all human rights, civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights, including the right to development Human rights situations that require the Council’s attention Human rights situation in Palestine and other occupied Arab territories Racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related forms of intolerance, follow-up to and implementation of the Durban Declaration and Programme of Action Technical assistance and capacity-building Communications report of Special Procedures* Communications sent, 1 December 2013 to 28 February 2014; Replies received, 1 February to 30 April 2014 Joint report by the Special Rapporteur on adequate housing as a component of the right to an adequate standard of living, and on the right to non-discrimination in this context; the Working Group on people of African descent; the Working Group on arbitrary detention; Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Belarus; the Working Group on the issue of human rights and transnational corporations and other business enterprises; the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Cambodia; the Special Rapporteur on the sale of children, child prostitution and child pornography; the Special Rapporteur in the field of cultural rights; the Independent expert on the promotion of a democratic and equitable international order; the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea; the Special Rapporteur on the right to education; the Independent Expert on the issue of human rights obligations relating to the enjoyment of a safe, clean, healthy and sustainable environment; the Working Group on enforced or involuntary disappearances; the Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions; the Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights; * The present report is circulated as received.