Sourcing the Arab Spring: a Case Study of Andy Carvin's Sources During the Tunisian and Egyptian Revolutions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PRISM Syrian Supplemental

PRISM syria A JOURNAL OF THE CENTER FOR COMPLEX OPERATIONS About PRISM PRISM is published by the Center for Complex Operations. PRISM is a security studies journal chartered to inform members of U.S. Federal agencies, allies, and other partners Vol. 4, Syria Supplement on complex and integrated national security operations; reconstruction and state-building; 2014 relevant policy and strategy; lessons learned; and developments in training and education to transform America’s security and development Editor Michael Miklaucic Communications Contributing Editors Constructive comments and contributions are important to us. Direct Alexa Courtney communications to: David Kilcullen Nate Rosenblatt Editor, PRISM 260 Fifth Avenue (Building 64, Room 3605) Copy Editors Fort Lesley J. McNair Dale Erikson Washington, DC 20319 Rebecca Harper Sara Thannhauser Lesley Warner Telephone: Nathan White (202) 685-3442 FAX: (202) 685-3581 Editorial Assistant Email: [email protected] Ava Cacciolfi Production Supervisor Carib Mendez Contributions PRISM welcomes submission of scholarly, independent research from security policymakers Advisory Board and shapers, security analysts, academic specialists, and civilians from the United States Dr. Gordon Adams and abroad. Submit articles for consideration to the address above or by email to prism@ Dr. Pauline H. Baker ndu.edu with “Attention Submissions Editor” in the subject line. Ambassador Rick Barton Professor Alain Bauer This is the authoritative, official U.S. Department of Defense edition of PRISM. Dr. Joseph J. Collins (ex officio) Any copyrighted portions of this journal may not be reproduced or extracted Ambassador James F. Dobbins without permission of the copyright proprietors. PRISM should be acknowledged whenever material is quoted from or based on its content. -

Mohamed Ramadan I Arrêté À Trois Reprises En Six Mois Au Cours De L’Année 2014

© IDHAE & IDHBB Institut des Droits de l’Homme des Avocats Européens – European Bar Human Rights Institute & Institut des Droits de l’Homme du barreau de Bordeaux – Human Rights Institute of the Bar of Bordeaux ISBN 978-99959-970-3-8 ISSN : 2354-4554 Le Code de la propriété intellectuelle interdit les copies ou reproductions destinées à une utilisation collective. Toute représentation ou reproduction intégrale ou partielle faite par quelque procédé que ce soit, sans le consentement de l’auteur ou de ses ayant cause, est illicite et constitue une contrefaçon, aux termes des articles L.335-2 et suivants du Code de la propriété intellectuelle 3 INSTITUT DES DROITS DE L’HOMME DES AVOCATS EUROPÉENS ISTITUTO DEI DIRITTI DELL'UOMO DEGLI AVVOCATI EUROPEI – INSTITUT FÜR MENSCHENRECHTE DER EUROPÄISCHEN ANWÄLTE – ΙΝΣΤΙΤΟΥΤΟ ΑΝΘΡΩΠΙΝΩΝ ΔΙΚΑΙΩΜΑΤΩΝ ΤΩΝ ΕΥΡΩΠΑΙΩΝ ΔΙΚΗΓΟΡΩΝ – INSTITUDO DE DERECHOS HUMANOS DE ABOGADOS EUROPEOS – INSTITUT LIDSKÝCH PRAV EVROPSKÝCH ADVOKATU – INSTYTUT ADWOKATÓW EUROPEJSKICH NA RZECZ PRAW CZŁOWIEKA – INSTITUT FOR MENNESKERETTIGHEDER AF EROPEAEISKE ADVOKATER – INSTITUTO DE DIREITOS HUMANOS DOS ADVOGADOS EUROPEUS EUROPEAN BAR HUMAN RIGHTS INSTITUTE Ce supplément SPECIAL ÉGYPTE est publié à l’occasion de La Journée mondiale de l’avocat en danger 2018 www.idhae.org 4 5 Éphéméride (non exhaustif) 1er mars 2013 : Romani Murad Saad condamné par contumace à un an de prison et 500 Livres égyptiennes EGP (52,30 €) d'amende pour diffamation de la religion. 29 mars 2013 : Maheinour el-Massry, Mohamed Ramadan, Amr Said, Mohamed Samir et Nasser Ahmed arrêtés à Alexandrie et victimes de violences pour avoir voulu défendre des manifestants arrêtés lors d’une manifestation. -

Petition To: United Nations Working

PETITION TO: UNITED NATIONS WORKING GROUP ON ARBITRARY DETENTION Mr Mads Andenas (Norway) Mr José Guevara (Mexico) Ms Shaheen Ali (Pakistan) Mr Sètondji Adjovi (Benin) Mr Vladimir Tochilovsky (Ukraine) HUMAN RIGHTS COUNCIL UNITED NATIONS GENERAL ASSEMBLY COPY TO: UNITED NATIONS SPECIAL RAPPORTEUR ON THE PROMOTION AND PROTECTION OF THE RIGHT TO FREEDOM OF OPINION AND EXPRESSION, MR DAVID KAYE; UNITED NATIONS SPECIAL RAPPORTEUR ON THE RIGHTS TO FREEDOM OF PEACEFUL ASSEMBLY AND OF ASSOCIATION, MR MAINA KIAI; UNITED NATIONS SPECIAL RAPPORTEUR ON THE SITUATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS DEFENDERS, MR MICHEL FORST. in the matter of Alaa Abd El Fattah (the “Petitioner”) v. Egypt _______________________________________ Petition for Relief Pursuant to Commission on Human Rights Resolutions 1997/50, 2000/36, 2003/31, and Human Rights Council Resolutions 6/4 and 15/1 Submitted by: Media Legal Defence Initiative Electronic Frontier Foundation The Grayston Centre 815 Eddy Street 28 Charles Square San Francisco CA 94109 London N1 6HT BASIS FOR REQUEST The Petitioner is a citizen of the Arab Republic of Egypt (“Egypt”), which acceded to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (“ICCPR”) on 14 January 1982. 1 The Constitution of the Arab Republic of Egypt 2014 (the “Constitution”) states that Egypt shall be bound by the international human rights agreements, covenants and conventions it has ratified, which shall have the force of law after publication in accordance with the conditions set out in the Constitution. 2 Egypt is also bound by those principles of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (“UDHR”) that have acquired the status of customary international law. -

President Obama's Approach to the Middle East and North Africa: Strategic Absence Paul Williams

Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law Volume 48 | Issue 1 2016 President Obama's Approach to the Middle East and North Africa: Strategic Absence Paul Williams Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/jil Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Paul Williams, President Obama's Approach to the Middle East and North Africa: Strategic Absence, 48 Case W. Res. J. Int'l L. 83 (2016) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/jil/vol48/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law 48 (2016) President Obama’s Approach to the Middle East and North Africa: Strategic Absence Paul Williams* Many commentators argue that the White House does not have a policy regarding the Middle East and North Africa. Based on observations of the White House’s foreign policy decisions over a breadth of seven years, this article argues that The White House does have a clear policy and it is one of Strategic Absence. The term Strategic Absence is used to describe political behavior that arises from a belief that sometimes, in foreign affairs, it is better to be absent rather than present. Strategic Absence has led to a degradation of American influence in the Middle East and has contributed to deteriorating conflict situations in Syria, Iraq, Yemen, and Libya. -

Young Global Leaders Annual Summit List of Participants

Young Global Leaders Annual Summit Yangon & Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar 3-5 June 2013 List of Participants As of 24 April 2013 Reuben Abraham Executive Director, Centre for Indian School of India Emerging Markets Solutions Business Tony Abrahams Co-Founder and Chief Executive Ai-Media Australia Officer Anu Acharya Founder and Chief Executive Officer mapmygenome.in India Vikram K. Akula Director AgSri Agricultural USA Services Pvt. Ltd Biola Alabi Managing Director, Africa Electronic Media Nigeria Network (M-Net) Suryani Senja Founder and Managing Director CULT Sdn Bhd Malaysia Alias Wilmot Allen Founder 1 World Enterprises USA Jamil Anderlini Beijing Bureau Chief The Financial Times People's Republic of China Martin Aspillaga Managing Director Salkantay Partners Peru Solomon Assefa Research Scientist IBM Thomas J. Watson USA Research Center Alexander Head, Fast Growth Markets and SAP AG People's Republic Atzberger China Strategy of China Asli Ay Managing Partner US Policy Metrics LLC USA Gina Badenoch Founder and Chief Executive Officer Ojos que Sienten AC Mexico Analisa Balares Chief Executive Officer and Founder Womensphere and USA Womensphere Foundation Jeremy Balkin President Karma Capital Australia Miranda A. Director of Sustainability, Wal-Mart Stores Inc. USA Ballentine Renewable Energy and Sustainable Facilities Katinka Barysch Deputy Director Centre for European United Kingdom Reform (CER) Karen Bell Managing Director and Head of Deutsche Bank AG Singapore Regional Management for Group Technology and Operations Jacques Beltran Senior Vice-President, Europe, CIS, Alstom International France Turkey Sasja Beslik Chief Executive Officer, Nordea Nordea Bank AB Sweden Investment Funds Neil Blumenthal Co-Founder and Co-Chief Executive Warby Parker Eyewear USA Officer David Boehmer Regional Managing Partner, Heidrick & Struggles USA Financial Services Jesmane Founder and Director Harvest USA Boggenpoel Bunty Bohra Chief Executive Officer Goldman Sachs India Services Private Limited Thomas J. -

To the OPC Holiday Party OPC in California and Paris

THE MONTHLY NEWSLETTER OF THE OVERSEAS PRESS CLUB OF AMERICA, NEW YORK, NY • December 2015 Journalist Safety Panel Highlights Growing Risks EVENT RECAP invulnerability you had, that press pass – that magical By Chad Bouchard thing that gave you this sort With violence against journalists of force field – that’s gone.” soaring to an all-time high in recent He called for more pres- years, freelancers and mainstream news media are seeking better ways sure from governments, to protect and give them the support and added that many of the they need to do their jobs. worst jailers of journalists Chad Bouchard On Dec. 16, the OPC, Bloomberg around the world are allies of the U.S. Left to right: Ambassador Raimonda Murmokaite, LLP and the Ford Motor Company Joel Simon, Anna Therese Day, Gregory D. co-sponsored a discussion about “They’re countries like Johnsen and Lara Setrakian. Egypt – which is the second journalist safety with a panel of jour- free speech. “We have to make noise leading jailer of journalists – Turkey, nalists and press freedom advocates. about this at all possible levels,” she In 2015, 69 journalists were Azerbaijan, Saudi Arabia. These are said. “Those who can’t stand the killed and 199 jailed worldwide, ac- countries where the U.S. has signifi- right to free information will never cording to the Committee to Protect cant influence, and it should be exer- defend the journalists.” Journalists. cising that influence.” Anna Therese Day, a freelance Joel Simon, the CPJ’s executive The panel also included Ambas- journalist and a founding board director, told attendees that jour- sador Raimonda Murmokaite, Lith- member of the Frontline Freelance nalists are increasingly targeted be- uania’s permanent representative Register, applauded work from cause of shifting power in the cur- to the UN. -

Complete Issue As

yber C y b e r O r i e n t Online Journal of the Virtual Middle East Vol. 6, Iss. 1, 2012 ISSN 1804-3194 CyberOrient Online Journal of the Virtual Middle East © American Anthropological Association 2012 CyberOrient is a peer-reviewed online journal published by the American Anthropological Association in collaboration with the Faculty of Arts of Charles University in Prague. Editor-in-Chief: Daniel Martin Varisco Managing Editor: Vit Sisler ISSN 1804-3194 http://www.cyberorient.net yber Index - Editorial Ines Braune – The Net Worth of the Arab Spring Page 4 - Articles Mohammed El-Nawawy and Sahar Khamis – Political Activism 2.0: Comparing the Role of Social Media in Egypt’s “Facebook Revolution” and Iran’s “Twitter Uprising” Page 8 Heidi A. Campbell and Diana Hawk – Al Jazeera’s Framing of Social Media During the Arab Spring Page 34 Donatella Della Ratta and Augusto Valeriani – Remixing the Spring!: Connective leadership and read-write practices in the 2011 Arab uprisings Page 52 Anton Root – Beyond the Soapbox: Facebook and the Public Sphere in Egypt Page 77 - Comments Mervat Youssef and Anup Kumar – Beyond the Soapbox: Facebook and the Public Sphere in Egypt Page 101 - Reviews Jon W. Anderson – The Digital Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy: Informati- on Technology and Political Islam Page 133 Marek Cejka – The Arab Revolution: The Lessons from the Democratic Uprising Page 141 3 yber C y b e r O rient, Vol. 6 , I s s . 1 , 2 0 1 2 The Net Worth of the Arab Spring Ines Braune Keywords Islam and civil society, Middle East, Arab Spring, information and communication technology, media studies, Middle Eastern studies, social networks When I was asked to be the guest editor of the current issue of CyberOrient, I realized this is a welcome opportunity to arrange and re-sort some aspects, points, and arguments about the role of the media during the Arab Spring. -

News Coverage Prepared For: the European Union Delegation to Egypt

News Coverage prepared for: The European Union delegation to Egypt . Disclaimer: “This document has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union. The contents of this document are the sole responsibility of authors of articles and under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of IPSOS or the European Union.” 1 . Thematic Headlines Domestic Scene Security Source Denies Bid on Saudi Envoy’s Life Made Electoral Campaigns Violations to Be Referred to HPEC Ganzouri: I’d Resign If Cabinet Reshuffle Took Place Shafiq Takes Lead in Presidential Campaign More MPs Refuse Vote of Censure against Government Weapons Found with Defense Ministry Sitter-Ins The Government Crisis Police Protests Escalate Al-Ahram Updates on Presidential Campaigns The Revolution Youth Coalition Supports Abu al-Futouh A demonstration Calling for the Return of the Saudi Ambassador An Interview with Hamadain Sabahi Presidential Elections Observers Islamic Mediation between Abu al-Futouh and Islamic Powers Police Officers Give the Minatory a Grace Shurouk Updates on Presidential Race Regional Development Israel Must Be Prepared for Future Confrontation with Egypt, Says Ex-Defense Minister 2 Newspapers (02/05/2012) Pages: 1 Author: Raja Leilah and Nasr Zaalouk A demonstration Calling for the Return of the Saudi Ambassador An official source denied what was reported by the London-based al-Haya newspapers about an alleged assassination attempt against the Saudi Ambassador to Egypt Ahmad Qattan in Cairo. While investigations continue in the case of the Egyptian national Ahmad al-Gizawi who is facing charges of drugs dealing in Saudi Arabia, dozens of Egyptians and political activists demonstrated in front of the Saudi Embassy in Cairo calling for the return of the Saudi Ambassador. -

How Journalists Used Twitter During the 2014 Gaza–Israel Conflict

International Journal of Communication 11(2017), 3497–3518 1932–8036/20170005 Reporting War in 140 Characters: How Journalists Used Twitter During the 2014 Gaza–Israel Conflict ORI TENENBOIM The University of Texas at Austin, USA Because Twitter may facilitate interconnectedness among diverse actors—elite and nonelite, inside and outside of a given national community—it can potentially challenge traditional war journalism that has typically been elite-oriented and nationally oriented. The present study examined this potential during the 2014 Gaza–Israel conflict. Based on a content analysis of Twitter messages by Israeli and international journalists, the study suggests that in wartime journalists on Twitter may have agency that can manifest in retweeting critical messages—not necessarily in the language of their national community—and conversing with people outside official power circles. However, institutional, cultural, and national forces still seem dominant, as particularly reflected in messages by journalists who are members of one of the conflicting parties. “Mr. Gates” on Twitter may have more agency than he had decades ago, but seems constrained by virtual national boundaries. By showing the extent of journalists’ agency and constraints, the study advances our understanding of war journalism in the digital age. Keywords: conflict, gatekeeping, Gaza, indexing, Israel, sources, Twitter, war “Trying to sleep but attacks are intense at 5 am [sic] in #gaza. Israel really striking hard now that Hamas left it with its own death toll,” a Wall Street Journal reporter posted on Twitter in July 2014 (Casey, 2014 [tweet]). “Wow—running to the stairwell with a baby and a three-year old girl—not easy,” an Israeli reporter tweeted after sirens went off in Tel Aviv alerting a rocket launch from Gaza (Ravid, 2014 [tweet]). -

The Future of Journalism and Politics Transcript by Angela Hart

The Future of Journalism and Politics Transcript by Angela Hart Georgetown CCT hosted a panel on The Future of Journalism and Politics on December 9, 2015, featuring Andy Carvin, Editor-in-Chief and Founder of reported.ly and Amber Phillips, Staff Writer for The Fix at The Washington Post moderated by CCT Professor Kimberly Meltzer and Dr. Stephanie Brookes, Professor of Journalism at Monash University. Professor Meltzer: Good morning, it’s wonderful to see all of you. Welcome to our panel today on The Future of Journalism and Politics and I’ll say more about that in a moment. We’re so excited to have this event, today, at Georgetown hosted by the CCT Program. For those of you who are not familiar with CCT, it stands for Communication, Culture, and Technology and we’re a two-year master’s degree program highly interdisciplinary. We have a few students, raise your hand if you’re a CCT student or faculty member, here today. I think the ones here sort of represent our students who are most interested in media and politics. Today is actually the last day of classes for the semester at Georgetown, so it’s great that any of you were able to make it; it’s a busy time of the year I know for all, and I want to thank CNDLS, which is Georgetown’s Center for New Designs in Learning and Scholarship for allowing us to use their conference room as some of you have heard me say, “As many universities are, Georgetown is often tight on space” so we were fortunate they were able to let us use this room, this morning. -

Lessons-Encountered.Pdf

conflict, and unity of effort and command. essons Encountered: Learning from They stand alongside the lessons of other wars the Long War began as two questions and remind future senior officers that those from General Martin E. Dempsey, 18th who fail to learn from past mistakes are bound Excerpts from LChairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff: What to repeat them. were the costs and benefits of the campaigns LESSONS ENCOUNTERED in Iraq and Afghanistan, and what were the LESSONS strategic lessons of these campaigns? The R Institute for National Strategic Studies at the National Defense University was tasked to answer these questions. The editors com- The Institute for National Strategic Studies posed a volume that assesses the war and (INSS) conducts research in support of the Henry Kissinger has reminded us that “the study of history offers no manual the Long Learning War from LESSONS ENCOUNTERED ENCOUNTERED analyzes the costs, using the Institute’s con- academic and leader development programs of instruction that can be applied automatically; history teaches by analogy, siderable in-house talent and the dedication at the National Defense University (NDU) in shedding light on the likely consequences of comparable situations.” At the of the NDU Press team. The audience for Washington, DC. It provides strategic sup- strategic level, there are no cookie-cutter lessons that can be pressed onto ev- Learning from the Long War this volume is senior officers, their staffs, and port to the Secretary of Defense, Chairman ery batch of future situational dough. The only safe posture is to know many the students in joint professional military of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and unified com- historical cases and to be constantly reexamining the strategic context, ques- education courses—the future leaders of the batant commands. -

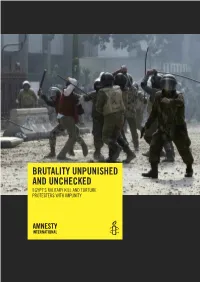

Brutality Unpunished and Unchecked

brutality unpunished and unchecked EGYPT’S MILITARY KILL AND TORTURE PROTESTERS WITH IMPUNITY amnesty international is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the universal declaration of human rights and other international human rights standards. we are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. First published in 2012 by amnesty international ltd peter benenson house 1 easton street london wc1X 0dw united kingdom © amnesty international 2012 index: mde 12/017/2012 english original language: english printed by amnesty international, international secretariat, united kingdom all rights reserved. this publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. the copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. to request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover phot o: egyptian soldiers beating a protester during clashes near the cabinet offices by cairo’s tahrir square on 16 december 2011. © mohammed abed/aFp/getty images amnesty.org CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................5 2. MASPERO PROTESTS: ASSAULT OF COPTS.............................................................11 3. CRACKDOWN ON CABINET OFFICES SIT-IN.............................................................17 4.