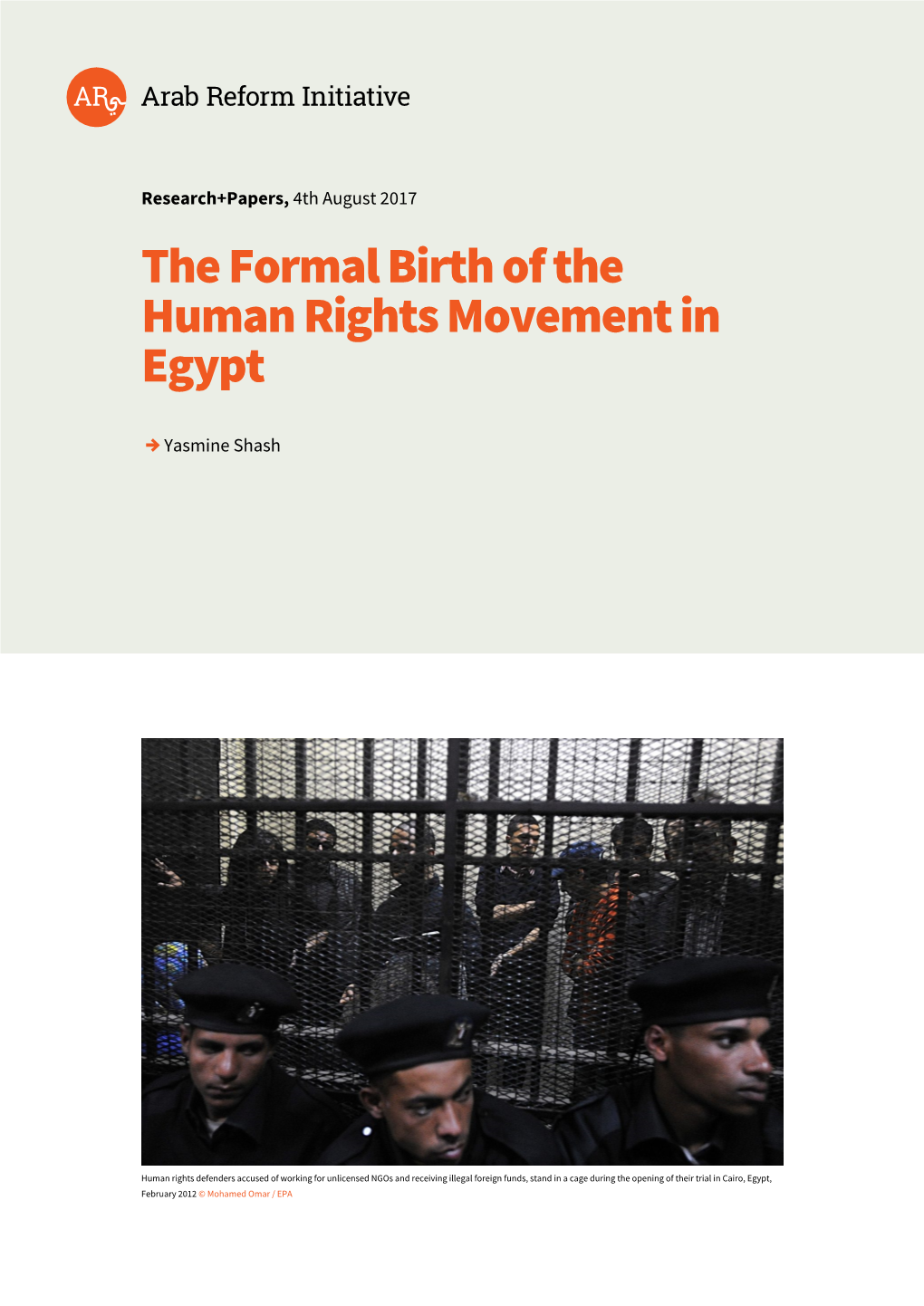

The Formal Birth of the Human Rights Movement in Egypt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sternfeld-Dissertation-2014

Copyright by Rachel Anne Sternfeld 2014 The Dissertation Committee for Rachel Anne Sternfeld Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Political Coalitions and Media Policy: A Study of Egyptian Newspapers Committee: Jason Brownlee, Supervisor Zachary Elkins Robert Moser Daniel Brinks Esther Raizen Political Coalitions and Media Policy: A Study of Egyptian Newspapers by Rachel Anne Sternfeld, B.A.; M.S.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2014 Dedication For Robert, who challenged us to contemplate difficult questions. Acknowledgements My dissertation would not be possible without the financial, intellectual and emotional support from myriad groups and individuals. The following are simply the highlights and not an exhaustive list of the thanks that are due. I am indebted to various entities at the University of Texas for providing the funding necessary for my graduate work. The Department of Government provided support for my coursework, awarded me a McDonald Fellowship that supported six months of fieldwork, and trusted me to instruct undergraduates as I wrote the dissertation. The Center for Middle Eastern Studies awarded me FLAS grants that covered two years of coursework and sent me to Damascus in the summers of 2008 and 2010. Beyond the University of Texas, the Center for Arabic Study Abroad (CASA) enabled me to spend a full calendar year in Cairo advancing my Arabic skills so I could conduct research without a translator. -

What Inflamed the Iraq War?

Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism Fellowship Paper, University of Oxford What Inflamed The Iraq War? The Perspectives of American Cartoonists By Rania M.R. Saleh Hilary Term 2008 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to express my deepest appreciation to the Heikal Foundation for Arab Journalism, particularly to its founder, Mr. Mohamed Hassanein Heikal. His support and encouragement made this study come true. Also, special thanks go to Hani Shukrallah, executive director, and Nora Koloyan, for their time and patience. I would like also to give my sincere thanks to Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, particularly to its director Dr Sarmila Bose. My warm gratitude goes to Trevor Mostyn, senior advisor, for his time and for his generous help and encouragement, and to Reuter's administrators, Kate and Tori. Special acknowledgement goes to my academic supervisor, Dr. Eduardo Posada Carbo for his general guidance and helpful suggestions and to my specialist supervisor, Dr. Walter Armbrust, for his valuable advice and information. I would like also to thank Professor Avi Shlaim, for his articles on the Middle East and for his concern. Special thanks go to the staff members of the Middle East Center for hosting our (Heikal fellows) final presentation and for their fruitful feedback. My sincere appreciation and gratitude go to my mother for her continuous support, understanding and encouragement, and to all my friends, particularly, Amina Zaghloul and Amr Okasha for telling me about this fellowship program and for their support. Many thanks are to John Kelley for sharing with me information and thoughts on American newspapers with more focus on the Washington Post . -

Mohamed Ramadan I Arrêté À Trois Reprises En Six Mois Au Cours De L’Année 2014

© IDHAE & IDHBB Institut des Droits de l’Homme des Avocats Européens – European Bar Human Rights Institute & Institut des Droits de l’Homme du barreau de Bordeaux – Human Rights Institute of the Bar of Bordeaux ISBN 978-99959-970-3-8 ISSN : 2354-4554 Le Code de la propriété intellectuelle interdit les copies ou reproductions destinées à une utilisation collective. Toute représentation ou reproduction intégrale ou partielle faite par quelque procédé que ce soit, sans le consentement de l’auteur ou de ses ayant cause, est illicite et constitue une contrefaçon, aux termes des articles L.335-2 et suivants du Code de la propriété intellectuelle 3 INSTITUT DES DROITS DE L’HOMME DES AVOCATS EUROPÉENS ISTITUTO DEI DIRITTI DELL'UOMO DEGLI AVVOCATI EUROPEI – INSTITUT FÜR MENSCHENRECHTE DER EUROPÄISCHEN ANWÄLTE – ΙΝΣΤΙΤΟΥΤΟ ΑΝΘΡΩΠΙΝΩΝ ΔΙΚΑΙΩΜΑΤΩΝ ΤΩΝ ΕΥΡΩΠΑΙΩΝ ΔΙΚΗΓΟΡΩΝ – INSTITUDO DE DERECHOS HUMANOS DE ABOGADOS EUROPEOS – INSTITUT LIDSKÝCH PRAV EVROPSKÝCH ADVOKATU – INSTYTUT ADWOKATÓW EUROPEJSKICH NA RZECZ PRAW CZŁOWIEKA – INSTITUT FOR MENNESKERETTIGHEDER AF EROPEAEISKE ADVOKATER – INSTITUTO DE DIREITOS HUMANOS DOS ADVOGADOS EUROPEUS EUROPEAN BAR HUMAN RIGHTS INSTITUTE Ce supplément SPECIAL ÉGYPTE est publié à l’occasion de La Journée mondiale de l’avocat en danger 2018 www.idhae.org 4 5 Éphéméride (non exhaustif) 1er mars 2013 : Romani Murad Saad condamné par contumace à un an de prison et 500 Livres égyptiennes EGP (52,30 €) d'amende pour diffamation de la religion. 29 mars 2013 : Maheinour el-Massry, Mohamed Ramadan, Amr Said, Mohamed Samir et Nasser Ahmed arrêtés à Alexandrie et victimes de violences pour avoir voulu défendre des manifestants arrêtés lors d’une manifestation. -

Petition To: United Nations Working

PETITION TO: UNITED NATIONS WORKING GROUP ON ARBITRARY DETENTION Mr Mads Andenas (Norway) Mr José Guevara (Mexico) Ms Shaheen Ali (Pakistan) Mr Sètondji Adjovi (Benin) Mr Vladimir Tochilovsky (Ukraine) HUMAN RIGHTS COUNCIL UNITED NATIONS GENERAL ASSEMBLY COPY TO: UNITED NATIONS SPECIAL RAPPORTEUR ON THE PROMOTION AND PROTECTION OF THE RIGHT TO FREEDOM OF OPINION AND EXPRESSION, MR DAVID KAYE; UNITED NATIONS SPECIAL RAPPORTEUR ON THE RIGHTS TO FREEDOM OF PEACEFUL ASSEMBLY AND OF ASSOCIATION, MR MAINA KIAI; UNITED NATIONS SPECIAL RAPPORTEUR ON THE SITUATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS DEFENDERS, MR MICHEL FORST. in the matter of Alaa Abd El Fattah (the “Petitioner”) v. Egypt _______________________________________ Petition for Relief Pursuant to Commission on Human Rights Resolutions 1997/50, 2000/36, 2003/31, and Human Rights Council Resolutions 6/4 and 15/1 Submitted by: Media Legal Defence Initiative Electronic Frontier Foundation The Grayston Centre 815 Eddy Street 28 Charles Square San Francisco CA 94109 London N1 6HT BASIS FOR REQUEST The Petitioner is a citizen of the Arab Republic of Egypt (“Egypt”), which acceded to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (“ICCPR”) on 14 January 1982. 1 The Constitution of the Arab Republic of Egypt 2014 (the “Constitution”) states that Egypt shall be bound by the international human rights agreements, covenants and conventions it has ratified, which shall have the force of law after publication in accordance with the conditions set out in the Constitution. 2 Egypt is also bound by those principles of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (“UDHR”) that have acquired the status of customary international law. -

Sourcing the Arab Spring: a Case Study of Andy Carvin's Sources During the Tunisian and Egyptian Revolutions

Sourcing the Arab Spring: A Case Study of Andy Carvin’s Sources During the Tunisian and Egyptian Revolutions Paper presented at the International Symposium on Online Journalism in Austin, TX, April 2012 Alfred Hermida Associate professor, Graduate School of Journalism, University of British Columbia Seth C. Lewis Assistant professor, School of Journalism & Mass Communication, University of Minnesota Rodrigo Zamith Doctoral student, School of Journalism & Mass Communication, University of Minnesota Contact: Alfred Hermida UBC Graduate School of Journalism 6388 Crescent Road Vancouver, BC, V6T 1Z2 Canada Tel: 1 604 827 3540 E-mail: [email protected] Abstract This paper presents a case study on the use of sources by National Public Radio's Andy Carvin on Twitter during key periods of the 2011 Tunisian and Egyptian uprisings. It examines the different actor types on the social media platform to reveal patterns of sourcing used by the NPR social media strategist, who emerged as a key broker of information on Twitter during the Arab Spring. News sourcing is a critical element in the practice of journalism as it shapes from whom journalists get their information and what type of information they obtain. Numerous studies have shown that journalists privilege elite sources who hold positions of power in society. This study evaluates whether networked and distributed social media platforms such as Twitter expand the range of actors involved in the construction of the news through a quantitative content analysis of the sources cited by Carvin. The results show that non-elite sources had a greater influence over the content flowing through his Twitter stream than journalists or other elite sources. -

Complete Issue As

yber C y b e r O r i e n t Online Journal of the Virtual Middle East Vol. 6, Iss. 1, 2012 ISSN 1804-3194 CyberOrient Online Journal of the Virtual Middle East © American Anthropological Association 2012 CyberOrient is a peer-reviewed online journal published by the American Anthropological Association in collaboration with the Faculty of Arts of Charles University in Prague. Editor-in-Chief: Daniel Martin Varisco Managing Editor: Vit Sisler ISSN 1804-3194 http://www.cyberorient.net yber Index - Editorial Ines Braune – The Net Worth of the Arab Spring Page 4 - Articles Mohammed El-Nawawy and Sahar Khamis – Political Activism 2.0: Comparing the Role of Social Media in Egypt’s “Facebook Revolution” and Iran’s “Twitter Uprising” Page 8 Heidi A. Campbell and Diana Hawk – Al Jazeera’s Framing of Social Media During the Arab Spring Page 34 Donatella Della Ratta and Augusto Valeriani – Remixing the Spring!: Connective leadership and read-write practices in the 2011 Arab uprisings Page 52 Anton Root – Beyond the Soapbox: Facebook and the Public Sphere in Egypt Page 77 - Comments Mervat Youssef and Anup Kumar – Beyond the Soapbox: Facebook and the Public Sphere in Egypt Page 101 - Reviews Jon W. Anderson – The Digital Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy: Informati- on Technology and Political Islam Page 133 Marek Cejka – The Arab Revolution: The Lessons from the Democratic Uprising Page 141 3 yber C y b e r O rient, Vol. 6 , I s s . 1 , 2 0 1 2 The Net Worth of the Arab Spring Ines Braune Keywords Islam and civil society, Middle East, Arab Spring, information and communication technology, media studies, Middle Eastern studies, social networks When I was asked to be the guest editor of the current issue of CyberOrient, I realized this is a welcome opportunity to arrange and re-sort some aspects, points, and arguments about the role of the media during the Arab Spring. -

News Coverage Prepared For: the European Union Delegation to Egypt

News Coverage prepared for: The European Union delegation to Egypt . Disclaimer: “This document has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union. The contents of this document are the sole responsibility of authors of articles and under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of IPSOS or the European Union.” 1 . Thematic Headlines Domestic Scene Security Source Denies Bid on Saudi Envoy’s Life Made Electoral Campaigns Violations to Be Referred to HPEC Ganzouri: I’d Resign If Cabinet Reshuffle Took Place Shafiq Takes Lead in Presidential Campaign More MPs Refuse Vote of Censure against Government Weapons Found with Defense Ministry Sitter-Ins The Government Crisis Police Protests Escalate Al-Ahram Updates on Presidential Campaigns The Revolution Youth Coalition Supports Abu al-Futouh A demonstration Calling for the Return of the Saudi Ambassador An Interview with Hamadain Sabahi Presidential Elections Observers Islamic Mediation between Abu al-Futouh and Islamic Powers Police Officers Give the Minatory a Grace Shurouk Updates on Presidential Race Regional Development Israel Must Be Prepared for Future Confrontation with Egypt, Says Ex-Defense Minister 2 Newspapers (02/05/2012) Pages: 1 Author: Raja Leilah and Nasr Zaalouk A demonstration Calling for the Return of the Saudi Ambassador An official source denied what was reported by the London-based al-Haya newspapers about an alleged assassination attempt against the Saudi Ambassador to Egypt Ahmad Qattan in Cairo. While investigations continue in the case of the Egyptian national Ahmad al-Gizawi who is facing charges of drugs dealing in Saudi Arabia, dozens of Egyptians and political activists demonstrated in front of the Saudi Embassy in Cairo calling for the return of the Saudi Ambassador. -

Brutality Unpunished and Unchecked

brutality unpunished and unchecked EGYPT’S MILITARY KILL AND TORTURE PROTESTERS WITH IMPUNITY amnesty international is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the universal declaration of human rights and other international human rights standards. we are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. First published in 2012 by amnesty international ltd peter benenson house 1 easton street london wc1X 0dw united kingdom © amnesty international 2012 index: mde 12/017/2012 english original language: english printed by amnesty international, international secretariat, united kingdom all rights reserved. this publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. the copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. to request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover phot o: egyptian soldiers beating a protester during clashes near the cabinet offices by cairo’s tahrir square on 16 december 2011. © mohammed abed/aFp/getty images amnesty.org CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................5 2. MASPERO PROTESTS: ASSAULT OF COPTS.............................................................11 3. CRACKDOWN ON CABINET OFFICES SIT-IN.............................................................17 4. -

Egypt Is an Ally- It Must Act Like One, NFFS Nov

NAPLES FLORIDA FEDERATION STAR November 2001 "Egypt is an Ally- It Must Act Like One" By Kenneth W. Stein The war against terrorism will not end if we neutralize savage killers, their training facilities and handlers, elusively clandestine bank accounts, and regimes that support them. This is also a battle of definitions, words, and marketing; it is about the contents of malice poured out against the U.S. by Arab newspapers and other Arab media outlets. With dozens of Arab writers and commentators spewing out venom toward the U.S., we need our Arab coalition partners and those who seek our support to reduce their hateful attacks on the U.S. Credit the Jordanian government for reducing anti-American media attacks. Origins for anti-American feeling can be found more or less regularly in the Palestinian, Saudi, Syrian, Iraqi, and London Arab press. But the U.S. has a special and necessary relationship with Egypt; it is in Cairo where the first effort to tone down anti-American anger must start. No, I do not suggest telling others what to write or what to think. But from allies, more should be expected and demanded. Twenty years after President Sadat's assassination, sustaining American foreign aid to Egypt remains central to our national interest. It should not stop. However, if we do not lean on Egypt, a long-time friend and leader of public Arab opinion, no remote chances exist for anti-American feeling to subside in the Middle East. Egypt's influence on Palestinian attitudes is greater than any other Arab state. -

Army Sets 48-Hour Ultimatum

AILY EWS TUESDAY, JULY 2, 2013 N D ISSUE NO. 2226 NEWSTAND PRICE LE 4.00 EGYPT www.thedailynewsegypt.com Egypt’s Only Daily Independent Newspaper In English BLOCK PARTY UNDER SIEGE SAD PANDA Cairo’s Mugamma is one of many Eight killed and 70 injured during New iconic character, emblematic government buildings nationwide an attack on the Brotherhood’s of revolutionary melancholy, to be blockaded by protesters headquarters in Moqattam flourishes in Cairo street art 2 3 8 Kerry confident about safety Army sets 48-hour ultimatum of US embassy in Cairo THE ARMED FORCES SAYS IT WILL PRESENT ITS OWN ROADMAP FOR THE 30 June protests draw comments from US Secretary COUNTRY IF POLITICAL FIGHTING DOES NOT END ON WEDNESDAY Kerry, President Obama, and German foreign minister By Nourhan Dakroury “What is clear right now is that al- By Basil El-Dabh, Rana Muham- though Mr Morsi was elected demo- mad Taha, and Hend Kortam Secretary of State John Kerry an- cratically, there is more work to be nounced on Sunday his keen attention done to create the conditions in which The Armed Forces will implement to the developments in Egypt and con- everybody feels their voices are heard,” a roadmap for the country if the firmed his confidence in the safety of the he concluded. Presidency and his opposition can- US embassy in Cairo as well as its staff. The United Nations warned on Mon- not resolve their differences within “Egypt is a great concern to all of day that the current political situation 48 hours. us,” Kerry said, explaining that he held in Egypt will have a “significant impact” “The Armed Forces reiterates talks with Gulf country leaders about on the democratic transformation of its call to meet the demands of the the political situation in Egypt, in addi- other countries in the Middle East. -

Horizons of the World : Imagining Coexistence in Language Through Understanding and Refiguring of Reality Ayman A

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Doctoral Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects 2008 Horizons of the world : imagining coexistence in language through understanding and refiguring of reality Ayman A. Moussa Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/diss Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Moussa, Ayman A., "Horizons of the world : imagining coexistence in language through understanding and refiguring of reality" (2008). Doctoral Dissertations. 188. https://repository.usfca.edu/diss/188 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of San Francisco HORIZONS OF THE WORLD: IMAGINING COEXISTENCE IN LANGUAGE THROUGH UNDERSTANDING AND REFIGURING OF REALITY A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the School of Education Department of Leadership Studies Organization and Leadership Program In partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Education by Ayman A. Moussa San Francisco May 2008 This dissertation, written under the direction of the candidate’s dissertation committee and approved by the members of the committee, has been presented to and accepted by the Faculty of the School of Education in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education. The content and research methodologies presented in this work represent the work of the candidate alone. -

Mobilisation Et Répression Au Caire En Période De Transition (Juin 2010-Juin 2012) Nadia Aboushady

Mobilisation et répression au Caire en période de transition (juin 2010-juin 2012) Nadia Aboushady To cite this version: Nadia Aboushady. Mobilisation et répression au Caire en période de transition (juin 2010-juin 2012). Science politique. 2013. dumas-00955609 HAL Id: dumas-00955609 https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-00955609 Submitted on 4 Mar 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne UFR 11- Science politique Programme M2 recherche : Sociologie et institutions du politique Master de science politique Mobilisation et répression au Caire en période de transition (juin 2010-juin 2012) Nadia Abou Shady Mémoire dirigé par Isabelle Sommier juin 2013 Sommaire Sommaire……………………………………………………………………………………...2 Liste d‟abréviation…………………………………………………………………………….4 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………5 Premier Chapitre. De la mort de Khaled Saïd au « vendredi de la colère » : répression étatique et mobilisation contestataire ascendante………………………………………...35 Section 1 : L’origine du cycle de mobilisation contestataire……………………………………...36